June 18, 2019 | Monograph

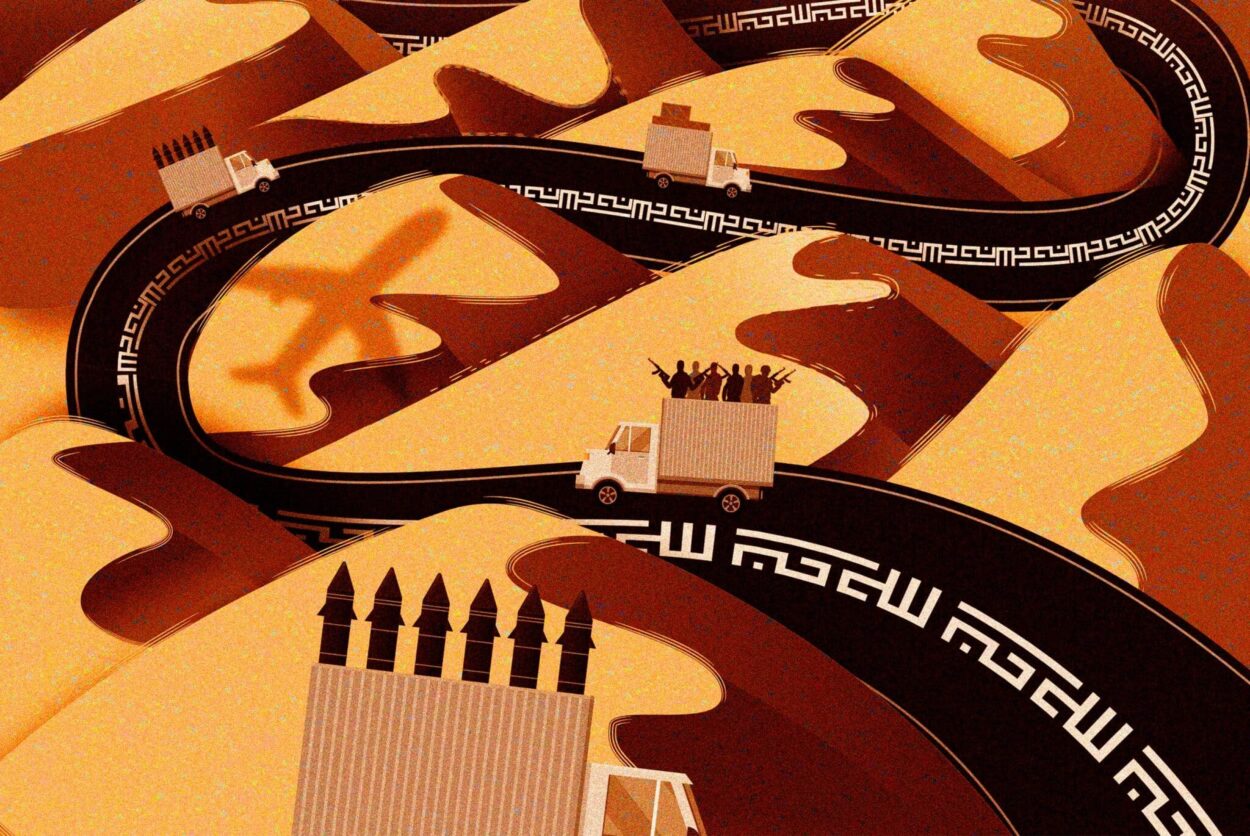

Burning Bridge: The Iranian Land Corridor to the Mediterranean

June 18, 2019 | Monograph

Burning Bridge: The Iranian Land Corridor to the Mediterranean

Foreword

By LTG (Ret.) H.R. McMaster

Chairman, FDD’s Center on Military and Political Power

Senior Fellow, Hoover Institution

In “Burning Bridge: The Iranian Land Corridor to the Mediterranean,” David Adesnik and Behnam Ben Taleblu shed fresh light and understanding on Iran’s sustained campaign to pursue hegemonic influence in the Middle East, export its revolutionary ideology, and threaten Israel and the West. Iran’s effort to establish a land bridge across Syria and Iraq is connected to a four decade-long proxy war that Iran is waging to pursue its revolutionary agenda. This study is important because it reveals the Islamic Republic’s intentions, describes in detail a critical element of Iranian strategy, and recommends practical steps necessary to counter that strategy and promote peace.

There has been a tendency to base U.S. Iran policy on wishful thinking rather than an understanding of the Islamic Republic’s actions and how they reveal its true intentions. For example, many hoped that the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or Iran nuclear deal – with its enticements of a cash payout up front, influx of foreign investment, and increased trade after the lifting of sanctions – would convince Iranian leaders to abandon their revolutionary agenda and end their hostility to Arab states, Israel, and the West. Instead, Iranian leaders, who are the beneficial owners of many of the companies that stood to profit from the contracts and letters of agreement signed after sanctions were lifted, used the influx of funds to intensify their proxy war in the region. Conciliatory approaches to Iran that gained in popularity in the United States and Europe in recent years failed because the principal assumption that underpinned those approaches was false. Treating Iran as a responsible nation state did not moderate the regime’s behavior. Wishful thinking led to complacency in confronting Iran’s most egregious actions and operations. The Iranian regime took full advantage of that complacency.

Iran’s strategy aims to weaken Arab states that are friendly to the United States and other Western nations. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) is perpetuating a sectarian civil war that is the fundamental cause of the humanitarian and political catastrophe across the region. It is the fear of Iran’s Shiite proxy armies that allows jihadist terrorist organizations to portray themselves as patrons and protectors of beleaguered Sunni communities. The cycle of sectarian violence allows Iran to export its ideology and apply the Hezbollah model broadly in the region. Iran wants weak governments in the region that are dependent on the Islamic Republic for support. The IRGC grows militias like Hezbollah in Lebanon that lie outside those governments’ control, which Iran can use to coerce those governments into supporting Iran’s designs in the region and reducing U.S. influence. Iran has that coercive power in Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq. The IRGC is also pursuing control of strategic territory in Yemen through its support of Shiite Houthi militias engaged with forces supported by the Saudis and Emiratis in that devastating civil war. The chaos that Iran’s strategy promotes sets conditions for the establishment of its land and air bridge across the region.

Wishful thinking on Iran among policymakers was based, in large measure, on the hope that a conciliatory policy would support moderates who would abandon the “Great Satan” and “Death to America” language and end their decades-long proxy wars. But policymakers should pay more attention to the regime’s actions as the principal means of assessing its intentions. The superb research in “Burning Bridge” reveals Iran’s determination to become the dominant power in the Middle East. That determination is based in an ideology that blends Marxism with Shiite millenarianism and imagines a world without the West. The true believers in the Islamic Revolution, from Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to the leaders of the IRGC, are in charge in Iran. Moderate reformers are in jail or out of the country. That is why policy must be based in an approach that is clearly aimed at countering the regime across the region and encouraging a shift in the nature of the Iranian regime such that is ceases its permanent hostility to its Arab neighbors, Israel, and the West. The Trump administration has adopted that approach and deserves support from the U.S. Congress as well as ally and partner nations.

The IRGC has been effective due, in large measure, to its unscrupulousness and talent for deception. The IRGC and the Iranian regime are vulnerable to a concerted multinational effort that aims to force a choice between continuing its murderous proxy war or behaving like a responsible nation. Concerted multinational action to shut down Tehran’s air bridge to Damascus and prevent a land bridge from becoming operational provides an opportunity to begin a sustained campaign to counter Iran’s destructive behavior. The clear recommendations at the end of this report are an excellent starting point for launching that campaign.

Illustrations by Daniel Ackerman/FDD

Executive Summary

- Iran and its proxy forces are establishing an unbroken corridor – dubbed a “land bridge” by Western analysts – from Tehran to the Mediterranean. The land bridge has the potential to accelerate sharply the shipment of weapons to southern Lebanon and the Golan front in Syria.

- The greater the strength of Iran and Hezbollah along Israel’s northern border, the greater the risk of escalation, leading to a regional war that directly threatens U.S. allies and U.S. interests across the Middle East.

- Iran has already opened one of the three primary routes from its own borders to the Mediterranean by retaking the key Syrian border town of Albu Kamal1 in November 2017. There are reports Iran has already begun to ship weapons through the town.2

- At present, the critical supply route for Iran remains the “air bridge” to Damascus, across which Iran has shipped advanced weapons to Hezbollah and tens of thousands of fighters to Syria since 2012.

- Iranian officials and proxy forces rarely mention the land bridge. Rather, their statements emphasize the struggle of the Iranian-led “Axis of Resistance” against the U.S. and its allies.

- The U.S. and its local partners currently hold blocking positions that have closed two of the three potential land bridge routes across the Middle East. The U.S. garrison at al-Tanf in eastern Syria sits astride the main highway from Baghdad to Damascus, obstructing one route. In addition, U.S. forces and their local partners in northern Syria block the northernmost route.

- Disrupting the land bridge should be a key U.S. objective, but Iran’s ambitions go far beyond an effective logistics supply route to southern Lebanon and the Golan front. Tehran’s goal is to subvert the regional order, export its revolution, and displace the U.S. as the leading power in the region.

- President Trump’s closest advisors have advocated a sustained effort to counter Iranian influence, yet unexpected policy reversals, such as the announcement of a withdrawal from Syria, have seriously damaged U.S. credibility in the region.

Introduction

President Trump’s closest advisers have repeatedly warned of Tehran’s determination to carve out a land bridge, or ground corridor, across the Middle East. “The regime continues to seek a corridor stretching from Iran’s borders to the shores of the Mediterranean,” explained Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, “Iran wants this corridor to transport fighters and an advanced weapons system to Israel’s doorsteps.”3 Shortly before his appointment as national security adviser, Ambassador John Bolton wrote, “Iran has established an arc of control from Iran through Iraq to Assad’s regime in Syria to Hezbollah in Lebanon.” This “invaluable geo-strategic position” enhances Tehran’s ability to threaten Israel, Jordan, and U.S. allies in the Persian Gulf.4 The president himself noted, “We don’t want to give Iran open season to the Mediterranean.”5

The concept of a land bridge has become integral to Washington’s assessment of Tehran’s strategic objectives. Lawmakers, scholars, and foreign correspondents emphasize its importance, yet have rarely examined the concept systematically. More importantly, it remains unclear how Iranian leaders think about the land bridge, a phrase they do not employ. Instead, Tehran speaks of an “Axis of Resistance” that unites Iran with Lebanese Hezbollah, the Bashar al-Assad regime, and other like-minded actors.

This report traces the evolution of the land bridge concept and places it in proper strategic context. Iran has already unblocked one route to the Mediterranean and would derive real strategic advantages from consolidating control over this route and the others that link Tehran to Baghdad, Damascus, and Beirut. Yet building a land bridge is just one element of Tehran’s strategy to establish itself as the dominant power in the Middle East. Logistical routes are necessary, but political and ideological similarities serve as the bedrock for the Axis of Resistance. Furthermore, Iranian ambitions include dominance in the Gulf, not just those countries along the route of the land bridge. A myopic focus on the land bridge would prevent the U.S. from addressing this broader threat.

Graphic: The northern (red) and southern (green) routes of the land bridge. The southern route has upper and lower branches that pass, respectively, through al-Qaim/Albu Kamal and al-Tanf. Source: Adapted from map by Franc Milburn in Strategic Assessment (Israel)

Still, disrupting the land bridge should be one important objective within a comprehensive strategy to reverse the gains Iran has made across the region, measured both in geographic terms and in its ability to intimidate or co-opt regional governments. The U.S. military presence in the region, especially in Iraq and Syria, serves the dual purpose of blocking certain land bridge routes and amplifying Washington’s diplomatic leverage. Rushed withdrawals, whether from Iraq in 2011, or the partial withdrawal now under way in Syria, have reinforced perceptions of the United States as less than dedicated to this fight.

Escalating sanctions pressure can constrain Iran’s access to the land bridge, to some extent. In the first months of 2019, the U.S. began to sanction select Shiite militias under Iranian control in Syria and Iraq,6 yet much work remains. For the moment, Iran actually derives greater strategic value from its aerial routes to Syria, or “air bridge,” which have comprised the main conduit since 2012 for sending weapons to Hezbollah and other Shiite militants to fight on Assad’s behalf. Accordingly, the U.S. has begun to intensify sanctions pressure on the commercial airlines that operate the air bridge.7 Capable diplomacy can also help to build regional and transatlantic support for shutting down Iran’s air bridge.

The cost of failure could be quite high. In the absence of decisive U.S.-led efforts to counter Iranian influence across the region, Iran may fully subordinate Iraq, increase deployments of the Shiite militias that serve as its foreign legion, and transform Syria into a forward base for Iranian aggression against Israel. Iran may thus plunge the region into war, even drawing in the United States. By taking preventive measures now, Washington can curtail the risk of such conflict.

Iranian Strategy and the Land Bridge

Less than three years ago, references to an Iranian land bridge were infrequent. Moreover, they did not refer to the same routes under discussion today. Before the autumn of 2016, it seemed implausible that Iran could establish control of a corridor from Tehran to the Mediterranean. By 2017, however, assessments evolved rapidly in response to developments on Syrian and Iraqi battlefields. By early 2018, there was a rough consensus on the meaning of “land bridge,” although its significance is disputed.

The Islamic Republic has had designs on the Middle East since its inception in 1979. Exchanging the pro-American orientation and nationalism of its predecessor for pan-Islamist, anti-Western, and anti-Zionist ideals, the new Iranian government sought to export its revolution,8 hoping to undermine U.S.-aligned governments in the Middle East. In the early 1980s, Iran saw an opportunity to confront Israel and support the cause of Lebanese Shiites. The regime deployed several thousand members of the newly formed Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) to the Bekaa Valley to begin training Lebanese fighters that would become Hezbollah.9 Iran also forged close ties with the Assad regime in Syria,10 whose proximity to Lebanon made it a critical source of support for the Lebanese group. Both the IRGC expedition to Lebanon and Iran’s drive to overthrow its Ba’athist adversary during the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), are early examples of Iran’s efforts to export its revolution.11

With good reason, analysts today describe Lebanese Hezbollah as “the most successful, and the most deadly, export of the 1979 Iranian revolution.”12 Emboldened by revolutionary ideology but also cognizant of its own conventional military shortcomings, Tehran’s regional security strategy came to rely on a constellation of non-state actors like Hezbollah.13 Iran’s cultivation, arming, financing, and training of such forces enabled the regime to advance the cause of Iranian hegemony at a comparably low cost, while limiting the prospects for escalation or direct retaliation against Iran, since its role was indirect.

The U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 removed Saddam Hussein from power and opened the door to a long-term Iranian effort to co-opt the government of Iraq. Nonetheless, establishing control of a land corridor across Iraq remained out of the question because of the Sunni insurgency that raged in western Iraq along the Syrian border. The insurgency subsided in 2007-2008, but the continuing U.S. military presence posed a similar challenge. The U.S. began to draw down its forces in 2009, but in 2011, the Assad regime lost control of eastern Syria to Sunni rebel forces, thereby threatening Iran’s regional designs.

Members of Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba. Source: Press TV (Iran)

The outbreak of war in Syria sparked discussions in Washington about an Iranian land bridge, yet the phrase initially had a different meaning. Instead of a corridor from Tehran to the Mediterranean, the term described a set of shorter routes from Syrian airports and seaports to regions in Lebanon under Hezbollah control. In 2012, Washington Post editor Jackson Diehl observed, “The Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad is Iran’s closest ally, and its link to the Arab Middle East. Syria has provided the land bridge for the transport of Iranian weapons and militants to Lebanon and the Gaza Strip.” “Without Syria,” he added, “Iran’s pretensions to regional hegemony, and its ability to challenge Israel, would be crippled.”14

In 2013, Matthew Levitt, an expert on Hezbollah, said it was imperative for Assad to “maintain a land bridge for the resupply of Iranian weapons” to the Lebanese group by preserving control of Syria’s Mediterranean coastline.15 Shipments that arrived in the ports of Tartus, Baniyas, and Latakia could then move directly southward into Lebanon. Although cargo vessels are more cost effective than aircraft and have far greater capacity, they are also far more susceptible to interdiction. Thus, Assad became increasingly dependent on shipments via air, which began in early 2012, when Iraq first opened its airspace to Syria-bound flights from Iran. Iraq suspended the flights shortly after an April phone call from President Obama to Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, yet the flights resumed several months later.16 In effect, Iran was employing an air bridge to send manpower and weapons to Syria, some of which would move by land into Lebanon.

The Land Bridge Evolves

Iran’s growing influence in Iraq, thanks to the rise of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMFs), spurred a redefinition of the land bridge as a corridor from Tehran to the Mediterranean, not just Damascus to Lebanon.17 While the PMFs are neither exclusively Shiite nor uniformly pro-Iran, they served as a vehicle for Iranian proxies such as Kataib Hezbollah, Asaib Ahl al-Haq, and others to expand their influence. In late 2015, Ali Khedery, formerly a top adviser to several U.S. ambassadors in Iraq, warned, “Iran may play a spoiler role and seek to preserve its ability to attack Israel by securing its land bridge across Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon.”18

The first thorough assessments of the extended land bridge to the Mediterranean appeared in the fall of 2016, beginning with a Wall Street Journal story about Sunni Arabs’ fear that the fall of the Islamic State would be followed by “a potentially more dangerous challenge: a land corridor for Tehran to Beirut” under Iranian control.19 In October, the UK’s Guardian published the first detailed map of the alleged route, which crossed from Iran into central Iraq, then swung to the northwest, passing through the town of Sinjar, before entering Syria at the Rabia border crossing.

Graphic: The northern land bridge route as originally conceived in October 2016. Source: The Guardian (UK)

The accompanying story presented the emerging bridge as an “historic achievement more than three decades in the making.” According to correspondent Martin Chulov, the land corridor was one of Tehran’s “most coveted projects – securing an arc of influence across Iraq and Syria that would end at the Mediterranean Sea.”20 Drawing on anonymous sources he identified only as “regional officials,” Chulov asserted that Iran had a specific and well-established plan for building the land bridge, “coordinated by senior government and security officials in Tehran, Baghdad, and Damascus,” all under the guidance of IRGC Quds-Force (IRGC-QF) commander, Major General Qassem Soleimani.21

Other Western observers agreed that a northerly route was the most plausible. As part of their drive toward Mosul, PMF units loyal to Tehran increased their presence in northwest Iraq. Following the PMF units’ capture of the airport in Tal Afar, a key city on the road from Mosul to Sinjar, analyst Hanin Ghaddar warned, “Iran May Be Using Iraq and Syria as a Bridge to Lebanon.” She noted, “If Iran succeeds, the three countries caught in the midst of this strategy could lose whatever is left of their sovereignty.”22

The Southern Route Emerges

Ideas about the land bridge continued to evolve along with developments on the battlefield. In 2017, an Iranian-led coalition that included Shiite foreign militias and Assad regime forces began moving eastward toward the Syrian border with Iraq, eventually reaching the border town of Albu Kamal in the Euphrates River valley. In May, Israeli journalist Ehud Yaari assessed that Iran was “building two land corridors to the Mediterranean.”23 The first was the northern corridor that crossed through Sinjar. The second route followed the Euphrates out of Baghdad, snaking through the desert to the west and north until it reached the border town of al-Qaim before crossing into Syria. In October, Iraqi government forces and PMF units took the Rabia border crossing, previously controlled by Iraqi Kurds, reinforcing concerns about the northern route.24

As summer ended in 2017, government officials, journalists, and policy experts began to discuss the land bridge with greater frequency. The Associated Press and Reuters both ran stories examining the land bridge and the Shiite militias that operated along its path.25 A key indicator of sustained interest in the land bridge was the work of INSS, an Israeli government-sponsored think tank, which published two lengthy treatments of the subject. The first article specified in detail three potential routes for the land bridge. In addition to the northern route and the southern route along the Euphrates, it identified a second southern route coming out of Baghdad and running toward the intersection of the Iraqi, Syrian, and Jordanian borders. The second article emphasized the indispensable role of Iranian-backed Shiite militias in securing a land corridor.26

Michael Pregent of the Hudson Institute has produced maps that illustrate the presence of these militias across most of Iraq. “Call it Iran’s land-bridge, a permissive environment, or a FastPass to Syria – whatever you want to call it – it exists,” he told Congress.27 The phrase “permissive environment” underscores that important sections of the land bridge consist of zones of political influence rather than stretches of road or strategic border crossings. Throughout much of Iraq, Iranian-backed militias can operate without interference from security forces under the prime minister’s control. Thus, when moving illicit cargos, the militias can choose whichever route is most suitable at the moment.

In the fall of 2017, the land bridge took center stage for the first time at a congressional hearing titled “Confronting the Full Range of Iranian Threats.” In his opening remarks, Rep. Ed Royce (R-CA), then chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, said,28

[It is] critical that we stop Iran from completing a “land bridge” from Iran to Iraq to Syria to Lebanon. This would be an unacceptable risk and, frankly, a strategic defeat. It is not just Israel’s security on the line. I feel that if Iran secures this transit route, it will mark the end of the decades-long U.S. effort to support an independent Lebanon. Jordan’s security, too, would be imperiled.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu began to express similar concerns. In June 2017, Netanyahu made a brief reference to the Iranian pursuit of a land bridge.29 He elaborated further during a March 2018 address in Washington, saying the bridge would trace a route from “Tehran to Tartus on the Mediterranean,” enabling Iran “to attack Israel from closer hand.”30

Iran’s “Resistance Highway”

Iranian officials have made few explicit references to a “land bridge.”31 Persian-language publications often use the term “land corridor” when they re-report Western analysis that refers to the land bridge.32 Persian-language sources do pay considerable attention to strategic geography, however. For Tehran, the “Axis of Resistance” (Persian: Mehvar-e Moghavemat) remains the relevant framework for its strategy in the region. The axis is a political construct that comprises a constellation of actors including Iran, allied states such as Syria, and non-state actors – principally Shiite militias – with varying degrees of ideological loyalty and operational independence, several of whom the U.S. has designated as terrorist organizations.33

Iran’s preference for the term Axis of Resistance indicates the prioritization of co-opting states and non-state actors to serve as vehicles for the regime’s foreign policy. Entities in the axis do not necessarily share an ethno-sectarian affiliation but rather an anti-Western disposition that Tehran can underwrite through political and material support. Seen in this light, Iran’s land bridge is a tool that can be used to supply this axis and actualize its strategic designs for the region.

There is no geographic criterion for membership in the axis, yet Iranian officials and pro-regime media outlets are cognizant of the strategic implications of axis geography.34 As the late Iranian President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani explained to an Iraqi official in 2012, “Syria must not turn out in such a way that your and our paths are shut. We must possess Syria. If the thread from Lebanon to here is cut, bad events will happen.”35 Rafsanjani’s comments underscore how Syria – more so than Iraq – is central to Iran’s regional designs.36 Iran needs Syria, and the land bridge is what logistically permits Iran to scale up its commitment to that front. More recently, then-IRGC Commander Major General Mohammad Ali Aziz Jafari said in 2017, “Syria’s bordering37 of occupied Palestine and its closeness to Iraq has created a decisive position for the Islamic Republic.”38 The importance of Syria was most acutely reflected in a 2013 comment by Hojjat al-Eslam Mehdi Taeb, the leader of a hardline think tank who said, “Syria is the thirty-fifth province and a strategic province for us… If we lose Syria, we cannot keep Tehran.”39

Relying on Iranian public statements has its problems given the regime’s penchant for hyperbole and deception. But Persian-language statements in open source publications remain one of the few indicators of the regime’s strategic intentions. Navigating this minefield is key to divining Iranian intentions, yet there is always a need to be cautious and guard against mirror imaging and self-deception.40

Militants carrying Hezbollah al-Nujaba’s flag. Source: Al-Masdar News

In at least three instances, Iranian officials have echoed Western talk of a land bridge. In a pro-IRGC outlet in 2015, IRGC Brigadier General Yadollah Javani asserted that America knows that “with a land connection through Iraq and Syria, [Iran] has become a decisive power on the Mediterranean coast.”41 In the summer of 2017, the senior adviser to the supreme leader for international affairs, Ali Akbar Velayati, touted the construction of a “resistance highway”42 connecting Tehran to Beirut through Mosul and Damascus.43 In 2018, the pro-Khamenei Khatt-e Hezbollah newsletter noted that resistance forces had “reopened a land corridor of resistance between Tehran, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, and now, they have provided the necessary infrastructure in the Golan to create the upper hand of resistance against the Zionists.”44

Several Iranian analysts have also used the term “land corridor of resistance.” One Iranian foreign policy watcher opined in the semi-official Tasnim News Agency that U.S. military aims in Syria are fundamentally two-fold: “contesting Iran’s power and preventing the establishment of a land corridor of resistance.”45 Others have used the term to describe the dividends that battlefield developments in Syria afford Iranian strategy. “Albu Kamal was the last Daesh [Islamic State] base in the border area of Syria, and it is expected that in the next few days this city will be fully liberated,” wrote one analyst in a hardline news outlet. “The liberation of this city also means the completion of the last ring of the land corridor of resistance, upon which, for the first time Tehran will reach the Mediterranean coast and Beirut by land; a development which has been rare in the several thousand year history of Iran.” He added that America sought to “avoid the realization of this land route.”46

Graphic: Select members of Iran’s “Axis of Resistance.”

The paucity of Persian-language references to the land bridge may be deliberate. “Iranian leaders avoid publicly speaking about their aim to link to so-called ‘axis of resistance,’” wrote Associated Press correspondents Bassem Mroue and Qassim Abdul-Zahra in 2017.47 Similarly, Tehran has often under-reported its fatalities in the Syrian conflict,48 while emphasizing their sacrifice when it suits the regime’s purposes.49

However, Tehran’s proxies are less discrete about their ambitions. “Our aim is to prevent any barriers from Iraq to Syria all the way to Beirut,” a spokesperson for the Iraqi Shiite militia Kataib Hezbollah told Mroue and Abdul-Zahra, “The resistance is close to achieving this goal.” Likewise, the Syrian minister of information said, “The aim is for a geographical connection between Syria, Iraq and the axis of resistance.”50 On background, authorities in Tehran are sometimes as forthcoming as their proxies. An unnamed IRGC official told the Wall Street Journal, “Creating a land corridor through Iraq and Syria is a key goal for Iran to bolster its defense against regional enemies.”51

Iranian media have certainly reported on plans to build transportation infrastructure for a land bridge, although without commenting on its military utility. Re-reporting Arab press, the Iranian media has said that a major highway stretching 1,700 kilometers will connect Iran to Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon.52 It is unclear if this highway is what Iran’s Minister of Roads and Urban Development Mohammad Eslami may have been referring to in February 2019 when he hailed the construction of a new highway linking three cities in western Iran, and gave notice of plans to extend it into Iraq and Syria.53 In April 2019, Iran’ First Vice-President Eshaq Jahangiri declared Iran’s intention to “connect the Persian Gulf from Iraq to Syria and Mediterranean via railway and road.”54

In August 2018, an Iranian official announced that Iran intended to build a rail link connecting the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean, from Basra in southern Iraq to Albu Kamal on the Iraq-Syria border, proceeding towards Deir Ez-Zour in northeast Syria.55 He suggested the project would be attractive to China, with whom Iran is eager to enhance its economic relationship to offset U.S. sanctions. During Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s March 2019 trip to Iraq, Iran reportedly signed a memorandum of understanding for a railway project designed to “connect Iraq’s southern oil-rich city of Basra to Iran’s border.”56 It is unclear if this project is part of the rail link to the Mediterranean envisioned in August 2018. In April 2019, the head of the Iraqi Republic Railways Company also echoed news about a transnational railway between Iran, Iraq, and Syria.57

Although China has not announced plans to develop a rail network through Iraq and Syria, it has worked with Iran in the context of its One Belt One Road initiative.58 China has also invested heavily in Iran’s domestic rail network, and aims to connect Iran to Central Asia via rail.59 Additionally, a Chinese firm built the high-speed trains used on the existing Baghdad-Basra rail line.60 Restored U.S. sanctions, however, may raise the costs of Chinese infrastructure partnerships with the Islamic Republic. Already, Chinese banks appear skittish to process Iran-related transactions.61

Debating the Land Bridge

Is the construction of the land bridge an epochal event or merely a footnote to the 40-year struggle between Iran and its adversaries? Ambassador James Jeffrey, who now serves as Special Representative for Syria Engagement, told Congress that he disagreed with all those who “have pooh-poohed the idea of a land bridge.” He explained, “The Iranians, for good reason … fear our ability to intercept and force down aircraft if we really get upset.” He continued, “We control the air in the Middle East. We don’t control the sand. That is what they want to do.”62

With the Assad regime now stabilized and the war in Syria at a low boil, there is arguably no urgent need for Iran to open a land-based supply route. Yet the uncertainty of the future provides ample motivation for Iran to find an alternative to its air corridor. So far, Israel has restricted itself to interdicting shipments of advanced weapons once they are on the ground. Yet it could also attack cargo planes in flight, as could the United States. For now, the risk of antagonizing Russia may prevent this kind of escalation, but Tehran cannot take for granted that this will always be the case.

The following three sections analyze the relative utility of the land bridge, versus the air bridge, for moving personnel, weapons, and other supplies.

Moving Personnel

Iran and Syria currently rely on civilian airliners to rotate wave after wave of militia fighters into Syria, where they have fought on Assad’s behalf. Whereas Hezbollah fighters can cross the Lebanese-Syrian border by land, that is not an option for Afghans, Pakistanis, or even many Iraqis. These foreign fighters usually serve in Syria for only several months at a time and take heavy casualties, so there is a constant need to bring in reinforcements.

In early 2018, an FDD study estimated that Iran maintains about 15,000 Shiite foreign fighters in Syria, not including those deployed by Lebanese Hezbollah.63 Air transport is likely sufficient to enable their rotation; Farzin Nadimi of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy estimated that Iranian and Syrian aircraft brought more than 21,000 passengers into Damascus in a two-month period in 2017.64

Still, because of sanctions, Iran and Syria rely on a small and aging fleet of commercial aircraft. Nadimi lists about a dozen commercial aircraft that have been responsible for most of the air bridge flights.65 After the conclusion of the Iran nuclear deal in 2015, Tehran placed orders for hundreds of planes worth tens of billions of dollars from Western manufacturers. Only a handful arrived before the U.S. withdrawal from the nuclear deal in 2018 forced the orders’ cancellation.66

If too many of Iran and Syria’s commercial aircraft age out of service, a land bridge may become a necessary alternative to moving fighters by air. Furthermore, road transport is far less expensive per mile. Road vehicles can also adjust their routes quickly, make stops as necessary, and blend in with civilian traffic. Moving personnel on the ground also conserves air transport capacity for higher-value value cargos such as advanced weapons.

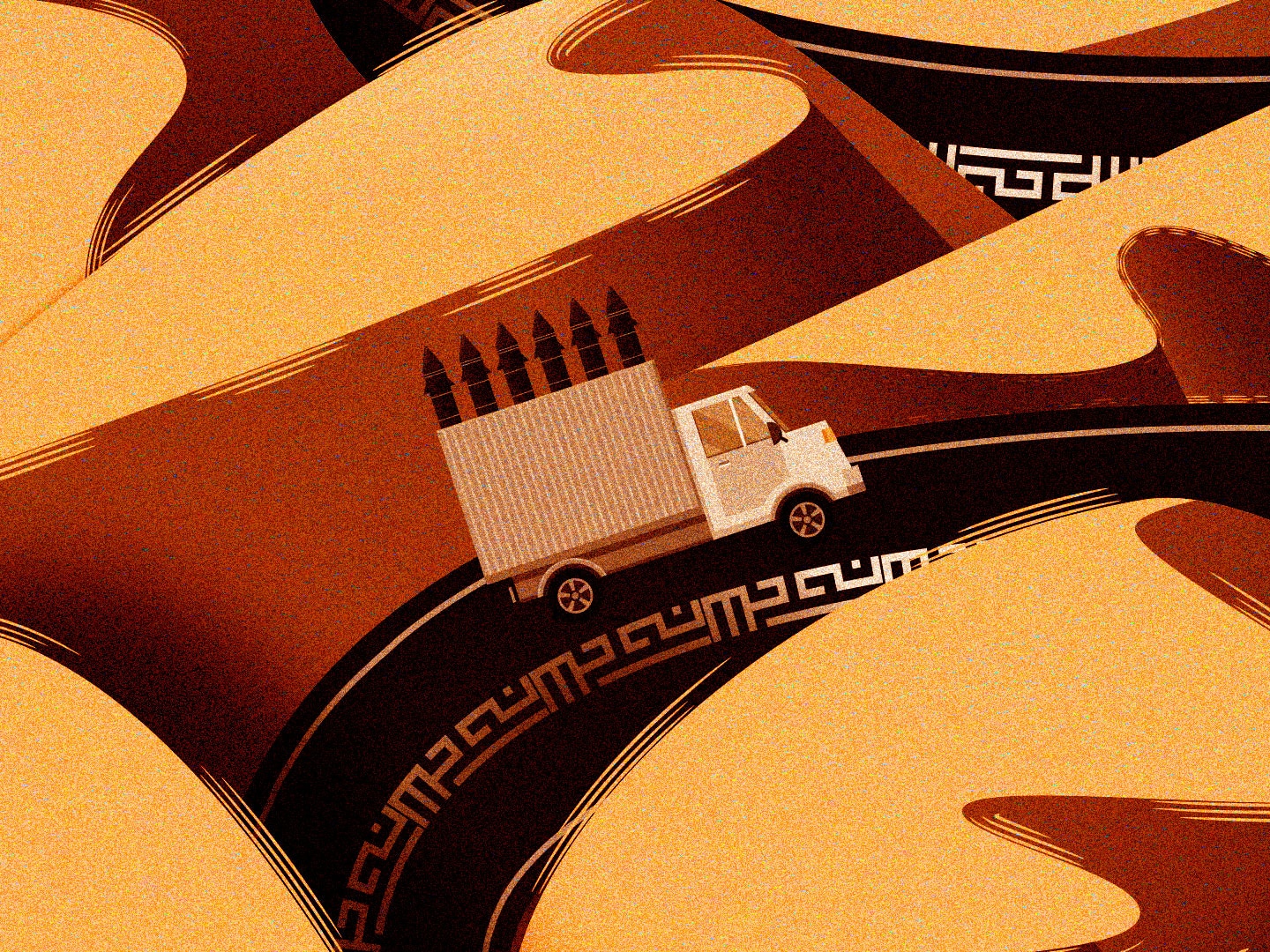

Moving Weapons

A land bridge would have substantial utility as a means of shipping weapons, such as light arms or shorter-range rockets and missiles.67 Yet thus far, the air bridge has also proven sufficient to meet Iran’s needs in this regard. Nadimi estimates that Iranian and Syrian aircraft were able to move 5,000 tons of supplies into Damascus during the two-month period he monitored.68

Moving that same cargo over land would require 125-250 trucks, since a tractor-trailer typically carries 20-40 tons of cargo, or the contents of two standard shipping containers.69 Yet given that trucks are readily available, whereas Iran and Syria have a small and aging fleet of commercial aircraft, a land route may become the more viable option. It even has the potential to expand Iran’s logistical capacity considerably.

While moving cargo by sea is more efficient than either air or ground transport, the risk of naval interdiction is considerable. In 2009, the U.S. Navy intercepted the MV Monchegorsk, which was carrying 2,000 tons of explosives from Iran en route to Syria.70

Moving Supplies

Iran certainly has had some success with seaborne transport of supplies other than weapons. After losing control of northeast Syria, which produced more than 90 percent of the country’s crude oil before 2011, the Assad regime became increasingly reliant on Iran for imports. Tankers dispatched by Iran, each holding nearly one million barrels of crude, offloaded their cargo at the Syrian port of Baniyas on a regular basis in 2018, although tougher enforcement of U.S. sanctions has created new barriers.71

Even so, Assad has also trucked in oil from northeast Syria, which the regime purchased from the Islamic State when it controlled the oil fields. The Syrian Kurds who displaced the Islamic State have continued to trade with Assad.72 However, given that one tanker can transport as much as 4,000 trucks, shipping oil by land is inefficient. It is also subject to disruption from the air, as demonstrated by U.S. strikes on Islamic State convoys.73 A secure land bridge may facilitate the trade of oil and other commercial goods, but not in quantities that have much strategic significance.

Operationalizing the Land Bridge: Routes and Impediments

Is the land bridge merely an aspiration, or is it already an operational supply route? If operational, how prone is it to disruption? Answers to these questions are unclear. In part, the confusion stems from conflicting premises about what would constitute an operational bridge. One can discern both minimalist and maximalist definitions. For minimalists, the land bridge exists if one can chart a course from Tehran to the Mediterranean without crossing terrain under the firm control of either the Islamic State or the U.S. For maximalists, the land bridge will remain incomplete until Iran and proxies can secure the entire corridor, enabling them to transport men and materiel without hindrance. In between these definitions lies a spectrum of intermediate options.

When the Guardian published the first major story about the land bridge in October 2016, it described a route whose viability depended on the cooperation of local powerbrokers, such as Syrian Kurdish militias and an Iraqi tribal sheikh. According to a follow-up report the next May, Iran had to shift the route 140 miles to the south to avoid the growing concentration of U.S. forces in northeast Syria.74 The next month, New Yorker correspondent Dexter Filkins described how Iran finally “secured” the land bridge in June when “pro-Iranian Shiite militias captured a final string of Iraqi villages near the border with Syria.” However, Filkins noted, “No Iranian trucks or other vehicles have apparently used the route yet.”75 Iran’s apparent breakthrough was temporary; within several months, the growing partnership between U.S. troops and Syrian Kurdish forces in northeast Syria compromised the land bridge’s original route.

In November 2017, the Syrian regime and Shiite militia forces with Russian support expelled Islamic State fighters from Albu Kamal on the Syrian-Iraqi border. This enabled them to cooperate with Iranian proxies in al-Qaim on the Iraqi side. Thus, according to the Jerusalem Post, “Iran [Put the] Finishing Touches on its ‘Bridge’ to the Golan.”76 Some accounts were more cautious, however. An article in the Israeli journal Strategic Assessment presented the first systematic evaluation of multiple routes for the land bridge, finding them all to be tenuous. It described Tehran’s pursuit of the land bridge as a “quest,” not a fact.77 In contrast, a French analyst concluded the land bridge is now “firmly established.” In his view, the capture of Albu Kamal represented a turning point in the history of the Levant, akin to the British victory at Fashoda in 1898 that established the empire as the premier colonial power in Africa.78

Who is correct? To address this question more thoroughly, it is necessary to examine the three principal routes associated with the land bridge: the northern route and the two branches of the southern route.

The Northern Route

- Open to Iran: No

- Key border crossing: Rabia (Iraq) to al-Ya’rubiyah (Syria)79

- Key roads: Highway 1 and Highway 47 in Iraq; Highway 6 and Motorway M4 in Syria

Assessment

If the U.S. maintains its strong partnership with Syrian Kurdish forces, this route will remain effectively closed to Iran. Yet if a U.S. withdrawal from Syria undermines that relationship, the People’s Protection Units (YPG), the primary Syrian-Kurdish militia, may open the northern route to Iran. This would be consistent with YPG cooperation with Iran and the Assad regime in pursuit of mutual interests during the first years of the war in Syria.80

Maps often identify Tehran as the starting point for any route associated with the land bridge. In practice, shipments would likely originate from wherever the regime produces and stores its materiel. Geography and political factors are likely to govern where Iranian shipments cross into Iraq. The border between the two countries runs for just under 1,000 miles, so there are numerous options.81

The northern crossings from Iran into Iraq lie within the Zagros Mountains, which present “choke points and environmental hazards during winter.” On the Iraqi side, some areas are under the control of Kurdish guerrillas resentful of how Iran treats its Kurdish population.82 Other Iraqi Kurds maintain cordial relations with Iran, but may not want to provoke Washington by cooperating with its main regional adversary. Thus, Iran might prefer to employ crossings further south where sympathetic elements of the Iraqi government or even Iranian-backed Shiite militias exercise control.

Once in Iraq, shipments along the northern route would make their way to the Rabia border crossing with Syria, which lies northwest of Mosul. There are also informal tracks that cross the border into Syria from northern Iraq. However, Kurdish forces aligned with the U.S. – at least for now – control the territory on the Syrian side of the border, so the route cannot become a major logistical artery.

Southern Route – Upper Branch

- Open to Iran: Yes

- Key border crossing: al-Qaim (Iraq) to Albu Kamal (Syria)

- Key Roads: Highway 12 (Iraq); Highway 4 (Syria)

Assessment

The upper southern route is now open to Iran, although it may not be fully secure.

As with the northern route, the choice of border crossings from Iran into Iraq is likely to reflect a combination of geography and politics. Crossing into Iraq’s Diyala province would shorten the distance to Baghdad, yet Diyala is where the Islamic State has made the most headway in re-establishing itself after the fall of the caliphate.83 Therefore, it would likely make sense to cross into Iraq further to the south, where the population is overwhelmingly Shiite.

From Baghdad, the upper southern route follows the Euphrates River northwest through Anbar province to the border town of al-Qaim. Anbar is the most uniformly Sunni region of Iraq, where both the anti-U.S. and Islamic State insurgencies were strongest. However, Kataib Hezbollah, an Iranian-backed Shiite militia, now has a strong presence near the border, including along roads in and out of al-Qaim.84

Across the border from al-Qaim is the Syrian town of Albu Kamal. As noted above, pro-regime forces took control of the town in November 2017. The official border crossing has not yet re-opened, yet Israeli reports suggest that Shiite militias are using dirt bypass roads built by the Islamic State.85 Last June, Israeli airstrikes targeted a town south of Albu Kamal, reportedly killing 20 members of Kataib Hezbollah who were apparently bringing Iranian weapons into Syria. An unnamed Israeli official told the Wall Street Journal that the purpose of the strikes was to show Iran that Israel would not tolerate a land bridge.86 This indicates that Tehran and its proxies may be close to activating the upper southern route.

While the Islamic State no longer controls territory in eastern Syria, there have been recent attacks near Albu Kamal. In early February, Russian jets conducted air strikes against Islamic State targets after an attack on pro-regime forces in the vicinity.87 According to a pro-Assad news outlet, attacks by the Islamic State forced Assad’s “Syrian Arab Army to reinforce their lines to prevent any potential infiltration.”88 These developments suggest the supply route running through Albu Kamal remains less than secure.

Another risk associated with Albu Kamal is the proximity of U.S. forces and their Syrian partners, since the town lies just across from the Euphrates and areas under control of the anti-Islamic State coalition. In 2018, the coalition launched more than 350 strikes on Islamic State targets in the vicinity of Albu Kamal.89 Past Albu Kamal, the terrain is flat and there would be few obstacles to crossing the remainder of Syria. The T4 air base, from which Iran launched an armed drone into Israel in 2018, lies about 200 miles west of Albu Kamal, across open desert.90

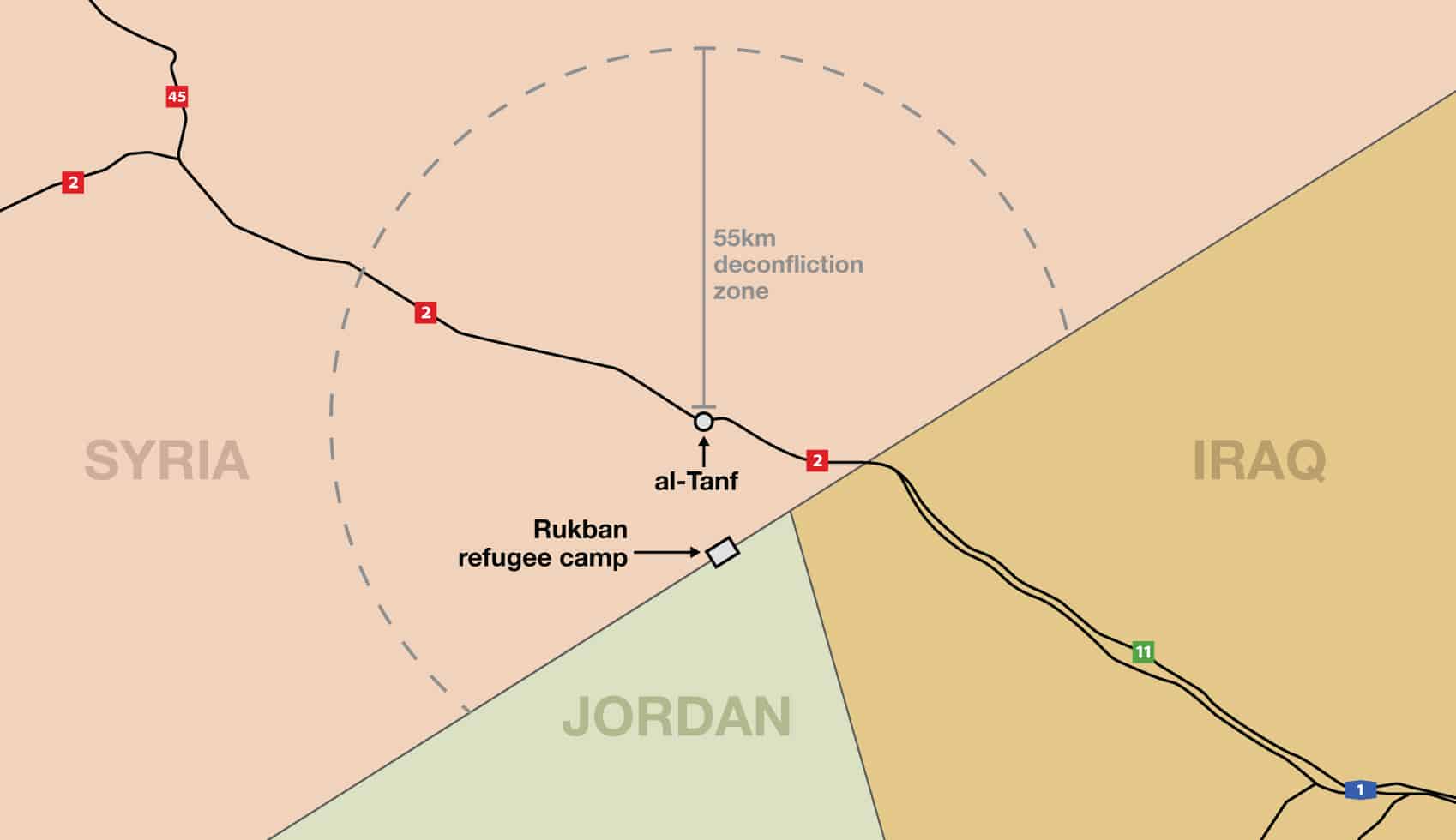

Graphic: The U.S. military base at al-Tanf sits astride the main highway from Baghdad to Damascus, blocking the lower branch of the land bridge’s southern route. Source: Foundation for Defense of Democracies

Southern Route – Lower Branch

- Open to Iran: No

- Key border crossing: al-Walid (Iraq) to al-Tanf (Syria)

- Key roads: Highway 11 or Expressway 191 (Iraq); Highway 2 (Syria)

Assessment

The lower branch of the southern route traces the shortest path from Baghdad to Damascus, although it runs directly through al-Tanf, the strategic town held by U.S. troops just west of the Syria-Iraq border.

From Iran to Baghdad, the lower branch is the same as the upper one. Then, about 75 miles west of Baghdad, the lower branch splits off and heads westward through the desert to the Syrian border. The route is ideal for trucks because it follows Iraq’s newly built toll road, the first in the country.92 After departing Iraq via the al-Walid border crossing, the southern branch reaches al-Tanf, which hosts roughly 200 U.S. troops and 300 fighters from Jaysh Maghawir al-Thawra (“Army of the Revolutionary Commandos”), a Syrian Arab partner force. In addition to conducting operations against the Islamic State, these troops maintain a “deconfliction zone” with a 55-kilometer (35-mile) radius.

Adversaries have continually tested the readiness of the U.S. and its partners to enforce the zone. In June 2016, the Pentagon criticized Russia for air strikes nearby that endangered U.S. and coalition forces.93 In May 2017, U.S. aircraft struck a convoy of Iranian-backed forces that included tanks and armored construction vehicles, which attempted to build fighting positions.94 In June 2017, the U.S. struck another convoy and shot down an Iranian drone. The U.S. downed a second Iranian drone later that month.95

5th Special Forces Group (A) Operation Detachment Bravo 5310 arrives to meet Major General James Jarrard at the Landing Zone at base camp Al Tanf Garrison in southern Syria

Assad and Putin also sought to dislodge the U.S. from al-Tanf by delaying or blocking assistance to the Rukban refugee camp, which lies within the U.S. exclusion zone. By blaming the U.S. for conditions at Rukban, Moscow and Damascus hope to shame the U.S. into withdrawal from al-Tanf. The camp has a population of 40,000-50,000 refugees who depend entirely on humanitarian aid. Russia and Assad stonewalled UN requests to deliver aid throughout 2018 while the Russians insisted that a U.S. departure from al-Tanf would solve the problem.96 Aid convoys finally arrived in November 2018 and February 2019. A UN official said there is no doctor in the camp and multiple children have died from the cold.97

Past al-Tanf, there are no major impediments to the land bridge. Shipments could follow Syrian highways for 150 miles directly to Damascus.

Clarifying U.S. Strategy toward Iran and the Land Bridge

President Trump’s sudden announcement of a U.S. withdrawal from Syria in December 2018 – partially reversed just two months later – reflects the uncertainty of U.S. strategy. Trump has pursued a policy of challenging Iran, reflected in his withdrawal from the JCPOA nuclear deal and reinstatement of comprehensive sanctions. Yet he has resisted his top advisers’ endorsement of a comprehensive effort to counter Iranian influence across the region, especially in Syria.98 Until the White House resolves this inconsistency, the administration will lack a clear framework for dealing with the land bridge.

Recognizing Iran’s determination to become the dominant power in the Middle East and export its revolution99 is the prerequisite for an effective strategy.

Iran prefers to employ asymmetric approaches that magnify its political and ideological advantages while neutralizing the superior wealth and conventional forces of the U.S. and its allies. This preference has led to an emphasis on ballistic missiles,100 a nuclear weapons program, and the patient cultivation of foreign proxies.

Iran’s greatest asset in the Levant and Iraq is its relationships with the other members of the Axis of Resistance. The land bridge helps to operationalize those relationships; it is one supporting element, not the centerpiece of Iranian strategy. Thus, the U.S. cannot afford to focus myopically on the land bridge. The administration’s mistake, however, has thus far been insufficient attention. This applies both to the land bridge and to the strategic significance of northeast Syria more broadly.

Secretary of State Pompeo has asserted, “Iran will be forced to make a choice: either fight to keep its economy off life support at home or keep squandering precious wealth on fights abroad. It will not have the resources to do both.”101 Syria is the most expensive of Tehran’s foreign adventures, so relieving U.S. pressure on the Assad regime would be self-defeating. The State Department estimates Iran spent $16 billion to prop up Assad since 2012.102 Much of Iran’s support was in the form of crude oil, since the Assad regime lost control of its oil fields in northeast Syria, which passed through the hands of the Islamic State before coming under the control of the U.S. and its Syrian partners. Northeast Syria also has valuable agricultural land, natural gas, and hydroelectric resources. A U.S. withdrawal would likely return these assets to Assad, substantially reducing the cost to Iran of supporting him.103

Similarly, a full U.S. withdrawal from Syria would remove substantial barriers to Iranian control of two potential routes for a land bridge, enabling Tehran to move men and weapons more efficiently. If U.S. troops departed from al-Tanf, the road from Baghdad to Damascus would effectively be open to Iranian traffic. An American withdrawal would also damage – perhaps irreparably – the close U.S. partnership with the YPG in northeast Syria. Fearing Turkish predation, the YPG would likely seek to secure protection from Assad and Tehran. In exchange for protection, Assad and Tehran would likely insist on freedom of movement within northeast Syria, among other things.

Disrupting the land bridge must be part of a broader effort to counter Iranian influence across the region, elements of which are already in place.104 The administration has escalated financial and political pressure on the IRGC by imposing additional Treasury Department sanctions and formally designating the IRGC as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO).105

The administration is also using Iranian missile launches, which have become harder to track due to delayed Persian-language public reporting, as flashpoints to highlight Iran’s habitual contraventions of UN Security Council Resolution 2231.106 The U.S. also seeks to expose107 Iran’s weapons proliferation by exhibiting captured Iranian weapons from battlefields across the region.108 However, none of these measures is a substitute for pushing back on Iran in the heart of the Middle East – Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon.109 Tackling the Iran issue in the three countries through which the land bridge passes would operationalize Washington’s nominal commitment to pushing back against Iranian influence across the region. In the absence of sufficient pushback, Iran will continue to escalate, gradually increasing the risk of a major conflagration.

Legal Challenges to the U.S. Mission

The authorized mission of U.S. forces in Syria and Iraq is to fight the Islamic State. During testimony in early 2018 before both the House and Senate Armed Services Committees, General Joseph Votel, then-head of U.S. Central Command, stressed that “countering Iran is not one of the coalition missions in Syria.”110 In practice, this means that U.S. forces cannot initiate operations against Iranian personnel, Shiite militias, or Assad regime forces. However, U.S. troops may act in self-defense if any of those forces pose a threat. For example, when Shiite militias and Iranian drones entered the exclusion zone around al-Tanf,111 this authority enabled the U.S. military to respond with force.

Despite such legal restrictions, American forces currently constitute the most effective impediment to Iran’s land bridge in Syria, simply because their presence serves as a deterrent. Thus, after reiterating that countering Iran is not the mission of U.S. troops in Syria, Votel said that U.S. troops could “impede Iran’s objectives of establishing lines of communication through these critical areas and trying to connect Tehran to Beirut.”112 Similarly, U.S. Special Representative for Syria James Jeffrey told Congress that the U.S military presence in Syria “has the ancillary effect of blocking further Iranian expansion.”113 Votel, Jeffrey, and other senior officials understand they must thread the needle of explaining how an American troop presence constrains Iran even if doing so is not those troops’ mission.114

Not all lawmakers appreciate this. Rep. Seth Moulton (D-MA), who sits on the House Armed Services Committee, challenged one administration official to explain National Security Advisor John Bolton’s comment that U.S. troops would remain in Syria until Iranian-backed forces leave. “That sounds to me like an operation against Iran,” which would be illegal, Moulton said.115 In the Senate, several Democrats introduced the Prevention of Unconstitutional War with Iran Act of 2018, barring any use of force in or against Iran without congressional authorization.116 Journalists have also raised questions regarding whether “mission creep” in Syria and Iraq could lead to accidental escalation of hostilities with Iran. 117

For over a decade, Congress has proven incapable of updating and revising its 2001 authorization for counterterrorist missions, despite a firm consensus that it has become outdated. Until conditions change on Capitol Hill, the administration should stand by the reasonably clear position it has elaborated: The threat posed by the Islamic State justifies the deployment of troops to Syria and Iraq, but it is prudent and appropriate to consider how those troops’ presence and posture also contributes to blocking Iran.

Policy Recommendations

The U.S. should rely on all elements of national power to contest Iranian influence in the Middle East. The recommendations below focus on disrupting the land bridge and integrating that objective into a coherent regional strategy.

Military

- Reinforce the U.S. and allied military presence in Syria. President Trump prevented a calamity of his own making by allowing 400 U.S. troops remain in Syria.118 However, the size of this force reflects political calculations, rather than military ones. The administration should prepare a contingency plan for deploying reinforcements, if 400 troops are incapable of executing a mission originally assigned to a contingent of 2,000. The White House should also persuade members of the anti-Islamic State coalition to send additional units, so the total force is closer to its pre-withdrawal number. This should ensure that the northern land bridge route remains closed to Iran.

- Keep U.S. troops at al-Tanf. News reports indicate that the 400 U.S. troops to remain in Syria will include a garrison of 200 at al-Tanf. Even before the reversal of Trump’s withdrawal order, senior officials were considering how to maintain the force at al-Tanf because of its ability to block Tehran’s optimal route for a land bridge.119 The base may also prove its continuing value as launch point for operations against the Islamic State, which would solidify the justification for a U.S. presence. Last May, for example, the Arab partner force at al-Tanf, Jaysh Maghawir al-Thawra, intercepted a $1.4 million shipment of illegal drugs intended to finance the Islamic State.120The U.S. should also continue working to ensure humanitarian aid reaches the refugee camp at Rukban. This would help to defuse accusations that the U.S. presence at al-Tanf is the cause of the refugees’ misery, even though Damascus and Moscow’s obstructionism is at fault. The U.S. should also lean on Jordan to facilitate aid provision, since Rukban lies directly on the Jordanian border. Washington should reassure Amman that cooperation would not result in requests to absorb tens of thousands of additional refugees, in addition to the hundreds of thousands already in Jordan.

- Prepare contingency plans for an operation to retake Albu Kamal. Iran and its proxies currently hold the upper hand in Albu Kamal. If a resurgent Islamic State – or a guerrilla force born from its ashes – ever reclaims the town and its environs, the coalition should consider retaking it. Doing so would close off the upper branch of the land bridge’s southern route, the only one now open to Iran.

- Build an enduring military partnership with Iraq. The U.S. should maintain current force levels in Iraq and expand efforts to train Iraqi units that are proficient, non-sectarian, and resistant to Iranian influence. The White House should also re-open discussion of the U.S. Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) and update the Strategic Framework Agreement that outlines the future of the U.S.-Iraq relationship.121 The Trump administration should offer to deepen the security relationship if politicians in Baghdad demonstrate resolve to counter Iran. It remains unlikely that Baghdad would dispatch its security forces to confront Iranian proxies operating the land bridge, yet they have the potential to deter such activity and share information with the U.S. military.

- Help the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) become a self-sufficient partner. There is an ongoing need for counterterrorist and defensive security operations now that the Islamic State has entered an insurgency phase. The U.S. should provide the SDF, which encompasses both Kurdish and Arab local partner forces, with the training and equipment necessary to smother the insurgency and maintain stability. These partner forces sacrificed several thousand fighters in the campaign against the caliphate and demonstrated their effectiveness on the battlefield. They should also develop the ability to defend northeast Syria against limited incursions across the Euphrates or its international borders.

- Support Israeli targeting of shipments that cross the Iranian air and land bridges. Israel has acknowledged carrying out more than 200 air strikes in Syria. The proximity of many Israeli targets to the Damascus airport suggests it is targeting weapons that arrive via Iran’s air bridge. Israeli strikes can also prevent the land bridge from becoming operational, or at least degrade its utility. The U.S. should employ its intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) assets to support Israeli missions, as appropriate. The U.S. should also make clear to Russia that Moscow should not interfere with Israeli operations, either directly or by indirect means such as allowing Iran to locate assets in proximity to Russian forces or selling advanced anti-aircraft systems to Assad.

- Request from Congress a narrowly tailored Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) to interdict illicit Iranian shipments of weapons crossing the Iraqi-Syrian border. For over a decade, lawmakers have agreed on the need for a new AUMF for counterterrorism, but lacked bipartisan common ground. Lawmakers should consider a new AUMF that includes authorization to interdict terrorist organizations’ illicit shipments of weapons across the Iraqi-Syrian border, which is likely to be the most important chokepoint on the land bridge. This authorization could serve as a powerful deterrent, since Iran is betting that weak American resolve will prevent Washington from using force to prevent the shipment of weapons to its proxies or by them. By scoping the AUMF as narrowly as possible, Congress can alleviate concerns that it is authorizing anything more than operations against designated terrorist organizations within a strictly limited geographic area.

Economic

- Ground the airlines that operate Iran’s air bridge to Syria. Four commercial carriers operate air bridge flights. The two Iranian carriers are Mahan Air, the country’s second largest, and Pouya Air, owned by the IRGC. The Syrian carriers are Syrian Arab Airlines and Cham Wings, a private firm. The U.S. has designated all four as terrorist entities, yet the impact has been limited. Mahan Air continues to serve destinations in Europe, the Gulf, and Southeast Asia.One new approach to hindering these carriers is for the U.S. to target the service providers, such as insurers and fuel suppliers, on which every airline depends to keep flying. In 2017, FDD’s Emanuele Ottolenghi identified 67 service providers that transact with Mahan Air. The Trump administration recently sanctioned several, but many remain.122 The U.S. has also begun to pressure friends and allies to hold Mahan Air accountable, which led Germany and France to expel the airline.123 Expanding this pressure campaign is urgent.

- Impose terrorism sanctions on all Iraqi proxies under control or acting on behalf of the IRGC-Quds Force.124 The U.S. designated the Quds Force as a terrorist organization in 2007 pursuant to Executive Order 13224; any entity under its control also merits designation under the same order. In March, the State Department added Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba and its leader, Akram al-Kabi, to the U.S. list of Specially Desginated Global Terrorists (SDGTs). Other targets likely eligible for designation include Asaib Ahl al-Haq, Kataib Imam Ali, Kataib Sayyid al-Shuhada, Liwa Zulfiqar, and Liwa Abu al-Fadl al-Abbas, along with their leaders. Kataib Hezbollah has been on the list since 2009 because of its earlier terrorist activities.125The Iraqi government, unfortunately, often lacks the political will to confront pro-Iranian forces. Through its political wing, al-Sadiqun, Asaib Ahl al-Haq won 15 seats in the 2018 parliamentary elections. Nonetheless, the most effective strategy for discrediting Tehran’s proxies is to demonstrate that they serve a foreign power. Contesting Iranian influence in Iraq will require a long-term effort that is mainly diplomatic and economic in nature.

- Impose terrorism sanctions on all proxy forces in Syria under control or acting on behalf of the IRGC-Quds Force or Lebanese Hezbollah. In January, the Trump administration designated two Shiite militias that the Quds Force deployed to fight on Assad’s behalf: the all-Afghan Fatemiyoun Division and the all-Pakistani Zeynabioun Brigade.126 The Quds Force has also helped the Assad regime to establish its National Defense Forces and Local Defense Forces. Other potential targets include Quwat Imam al-Rida and Liwa al-Sayydia Ruqayya (aka the Jaafari Force).127 Hezbollah – itself an extension of the Quds Force in most respects – also plays an integral role in training and advising proxy forces in Syria.

- Help Iraq reduce its economic dependence on Iran. Baghdad’s dependence on Tehran for imported electricity and other goods creates leverage that Iran can use to win concessions from Iraq for itself and its proxies.128 The U.S. should support multilateral efforts to generate the investment and foreign assistance necessary to revive the war-torn Iraqi economy and provide the population with basic services such as power, fresh water, and sewage. This can help Iraq chart its own course and have the strength to rebuff Iran.

- Escalate the U.S. economic pressure campaign against the Assad regime. The U.S. has a broad interest in holding the regime accountable for its war crimes and weakening it to the greatest possible extent. If the Caesar Act (S. 1/H.R. 31) becomes law, likely this year, the executive branch will have a range of new authorities it can employ to intensify sanctions. The Trump administration has already taken important steps to prevent Iran from exporting crude oil to Syria, although additional enforcement remains necessary.129Despite Europe’s objections to U.S. policy toward Iran, it is more aggressive in some respects with regard to sanctions on Syria, so Washington and Brussels should coordinate their efforts.130 Joint efforts could include the denial of reconstruction aid, unless Assad dramatically improves his record on human rights. The U.S. and EU should also work to reform the UN’s humanitarian assistance to Syria, which Assad distorts to subsidize his regime.131

- Escalate enforcement of sanctions on Hezbollah. Hezbollah is a primary recipient of weapons that cross the air bridge and land bridge. Under Tehran’s direction, it fights on Assad’s behalf and trains other Iranian proxies. In the long-term, the U.S. should work to break Hezbollah’s grip on the Lebanese state and dismantle its transnational criminal network, which funds its activities. For the moment, the Trump administration should employ the new authorities created by the Hizballah International Financing Prevention Amendments Act of 2018, or HIFPAA. The administration could target those in both the Lebanese public and private sectors who facilitate the arrival of weapons for Hezbollah across the air and land bridge.132

Political and Diplomatic

- Support Baghdad’s efforts to wrest control of PMF units away from the IRGC-Quds Force. This will be an uphill battle. Iraqi law has made the PMF into a recognized component of the country’s security forces, yet the prime minister’s authority over much of the PMF remains nominal. Regardless, the PMF receive substantial funding from Baghdad. The U.S. has worked to constrain the influence of these Iranian proxies, yet U.S. military commanders have praised them unnecessarily for their role in fighting the Islamic State. All American officials should now focus on exposing these proxies’ loyalty to Tehran, since Iraqi nationalism remains a potent force. The U.S. has a very limited ability to steer Iraqi politics, yet Iran’s proxies threaten the rule of law and popular government in Iraq. Their role in operating a potential land bridge remains crucial to Tehran’s plans.

- Work to resolve Turkish-Kurdish tensions in northeast Syria. Ankara has repeatedly threatened to take military action against the YPG in northeast Syria, where U.S. troops are also present. Ongoing violence between Turkish forces and the YPG could break apart the SDF, in which the YPG plays the leading role. It could also undermine the U.S. relationship with the Syrian Kurds, leading them to seek protection from Damascus, Moscow, and Tehran.133 In that scenario, the land bridge’s northern route would likely re-open. The U.S. should work to prevent such an outcome by informing Ankara that the U.S. will not tolerate a Turkish offensive in northeast Syria. At the same time, Washington could assure Ankara that the YPG will not support the Kurdish insurgency within Turkey, which is led by the PKK, a U.S.-designated terrorist organization.

- Help preserve the independence of local Kurdish and Arab partners in Syria. In addition to the ongoing military partnership necessary to prevent the resurgence of the Islamic State – see military recommendations above – the U.S. should maintain political relationships with local partners to help preserve their independence, principally from Damascus and its sponsors in Tehran and Moscow. While Assad and his partners may decline to mount a major military challenge to the security of northeast Syria, they have already begun to employ political and economic incentives to sow division from within. In that regard, the U.S. should provide stabilization funding on top of what its Gulf allies now provide. It should also help local partners find a market for their oil to replace the income they are losing as the U.S. pushes to prevent sales and trading with the Assad regime.

- Exploit the potential divergence of Russian and Iranian interests in Syria. Russia is no less determined than Iran to preserve the Assad regime; yet unlike Iran, it seeks to maintain positive relations with Israel. Thus, Russian forces conduct operations with Iranian partners or Iranian proxies in Syria, yet take no meaningful action to resist or deter the waves of Israeli airstrikes targeting Iranian assets. If Iran seeks to escalate the conflict with Israel in a reckless manner, Russia may become amenable to quiet cooperation with the Netanyahu government to reduce the threat. If the threat draws heavily on weapons moving across the land bridge, Russia may indirectly support an effort to disrupt it. On the other hand, Russian passivity in the face of Israeli air strikes in Syria may increase its interest in finding ways to placate Iran.

- Persuade the EU to hold Iran accountable for its destabilizing actions in the Middle East. The Iran nuclear deal remains a major point of contention between the U.S. and Europe, yet the EU and its leading members continue to condemn Iran’s destabilizing activities, especially its support for the Assad regime.134 In early 2018, the EU sought to entice Washington to stay in the nuclear deal by offering to impose sanctions against Iran’s ballistic missile program and against various militias and their commanders.135 Later, the EU imposed its first new terrorism sanctions on Iran following Tehran’s foiled attacks in Paris and Copenhagen, while Tehran has facilitated additional atrocities in Syria.136 Washington should explore whether its European partners are ready to take punitive measures against Iran and its proxies, including those involved in the land bridge.

Conclusion

The U.S. should work to shut down Tehran’s air bridge to Damascus and prevent a land bridge from becoming operational. These cannot be isolated efforts; they must be part of a comprehensive response to Iran’s growing influence in the region. As President Trump said in April 2018, “We don’t want to give Iran open season to the Mediterranean.”137 A failure to act would offer Tehran exactly that.