January 10, 2023 | Monograph

Strategy for a New Comprehensive U.S. Policy on Iran

Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- National Security Council

- Department of the Treasury

- Securities and Exchange Commission

- Department of State

- Department of Defense

- U.S. Agency for Global Media

- Department of Commerce

- Department of Energy

- Department of Homeland Security

- Department of Justice

- Department of Transportation

- Interdepartmental Country-Specific Strategies

- Conclusion

January 10, 2023 | Monograph

Strategy for a New Comprehensive U.S. Policy on Iran

FDD monograph edited by Mark Dubowitz and Orde Kittrie

Foreword

By Mark Dubowitz

The Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD) has developed a comprehensive plan for American policymakers and allies to support the Iranian people and confront the ongoing threats from the Islamic Republic of Iran. The strategy explains how Washington can deploy multiple elements of national power, providing specific and actionable recommendations for relevant agencies of the U.S. government.

The new revolution in Iran, combined with the regime’s military support to Russia, gives President Joe Biden and bipartisan majorities in Congress an opportunity to chart a new course. President Biden has recognized this imperative, vowing “we’re going to free Iran.”1 Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton recently said, “I would not be negotiating with Iran on anything right now, including the nuclear agreement.”2 Clinton emphasized that the United States should not “look like we are seeking an agreement [with Iran] at a time when the people of Iran are standing up to their oppressors.” 3

The administration has committed to Congress and to its allies that it is developing a “Plan B” to address the full spectrum of Iranian threats.4 We hope that this FDD plan is a useful contribution for policymakers developing that Plan B: providing intensive support to the Iranian people while pursuing decisive coercive and constraining pressure on the regime in Tehran.

Whatever the elements of an American plan, one thing should be clear: the Biden strategy must support the current protests inside Iran and the regular eruptions of anger toward the theocracy. Even before the Iranian street erupted in 2022, after regime security services brutally murdered 22-year-old Iranian woman Mahsa Amini, protests were occurring more often and with greater intensity.

In 2009, the Green Revolution saw hundreds of thousands of Iranians take to the streets to protest the fraudulent re-election of then Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Nationwide protests shook the Islamic Republic in late 2017 and have occurred regularly in the years since. In November 2019, an eruption of protests spurred the clerical regime to kill as many as 1,500 demonstrators, according to Reuters.5

Protesters gathered in August 2021 to challenge the regime over severe water shortages, leading security forces to kill several people.6 Other protests in recent years have challenged many of the regime’s malign policies, including its mismanaged economy, corruption, regional aggression, and human rights abuses.

The 2022 protests have gone even further, with thousands of Iranians abandoning calls for merely reforming the system; they now call for dismantling the regime. Protests have evolved from “Where is my vote?” to “What happened to the oil money?” to “Death to the Dictator!”7 This has increased the vulnerability of the Islamic Republic, making it more susceptible to collapse.

America should adopt a “roll back” strategy to intensify the existing weaknesses of the regime and to support the Iranian people’s goal of establishing a government that abandons the quest for nuclear weapons and is neither internally repressive nor regionally aggressive. To accomplish this, the American administration should take a page from the playbook President Ronald Reagan first used against the Soviet Union. In the early 1980s, Reagan seriously upgraded his predecessors’ containment strategy by pushing policies designed to roll back Soviet expansionism. The cornerstone of his strategy was the recognition that the Soviet Union was an aggressive and revolutionary yet internally fragile state that Washington could defeat.

Reagan’s policy was outlined in 1983 in National Security Decision Directive 75 (NSDD-75), a comprehensive strategy that called for the use of multiple instruments of overt and covert American power.8 The plan included economic warfare, support for anti-Soviet proxy forces and dissidents, and an all-out offensive against the regime’s ideological legitimacy.

The Biden administration should develop a new version of NSDD-75. The administration should address every aspect of the Iranian menace, not merely the nuclear program. A narrow focus on disarmament paralyzes American policy and has deterred the Biden administration from responding to Iran’s non-nuclear misconduct out of fear that Tehran would withdraw from nuclear negotiations. Engagement with the Islamic Republic as an end in itself has reflected the same delusions that American leaders entertained about Communist China. Those delusions of engagement made China more wealthy and more powerful and aggressive but did not moderate China’s rulers. The Iranian regime’s selection of Ebrahim Raisi — a mass-murdering9 cleric who is close to the supreme leader and received the lowest number of votes in a long history of fixed elections run by the Islamic Republic — as president should awaken American policymakers to the unmistakable conclusion: The Islamic Republic cannot be reformed; it must be rolled back. That is the message of the Iranian protesters.

President Biden also should explicitly abandon the objective of returning to the JCPOA (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action). Under that agreement, Tehran does not need to cheat to reach threshold nuclear-weapons capabilities. Merely by waiting for key constraints to sunset, the regime can emerge over the next eight years with an industrial-size enrichment program, a near-zero breakout time, an easier clandestine “sneakout” path to long-range, nuclear-armed ballistic missiles, much deadlier conventional weaponry, regional dominance, and a more powerful economy, enriched by an estimated $1 trillion in sanctions relief, thus gaining immunity from Western sanctions.10

A new U.S. strategy regarding Iran must contribute to systemically rolling back the regime’s power. Washington should target the regime’s terrorist networks, influence operations, and proliferation of weapons, missiles, and drones. Iranian military support for Vladimir Putin’s murder of Ukrainians, and growing Russian support for the Islamic Republic’s military expansion, should be a wakeup call for Washington and Europe that Tehran’s malign activities will not remain confined to the Middle East. Biden must develop a more muscular covert action program and green-light closer cooperation with allied intelligence agencies.

Most of Washington’s actions that could push back Tehran hinge on depleting the Islamic Republic’s finances. With strong encouragement from Congress, the pre-JCPOA Obama Treasury Department and the Trump administration ran successful economic warfare campaigns targeting the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and other regime elements. This campaign devastated Iranian government finances, led to high inflation, spurred a collapse in oil exports and the Iranian currency, and precipitated multiple rounds of street protests. In 2019, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei called the U.S. sanctions “unprecedented.”11 In the same year, then Iranian president Hassan Rouhani compared conditions in Iran to the country’s ravaged economy during the Iran-Iraq War from 1980 to 1988.12

But President Trump’s pressure campaign lasted only two years (from the snapback of U.S. sanctions in November 2018 to the end of his term in January 2021) — even less considering oil sanctions waivers were ended only in May 2019. If the Biden administration restores the JCPOA, economic pressure will evaporate as hundreds of potent sanctions are lifted and an estimated $1 trillion dollars in sanctions relief will be released to the regime, which will then fund regional aggression and internal repression.13 Already, the lackluster enforcement of existing sanctions by the administration has been a boon for the regime, as oil exports to China soar and Tehran leverages a clandestine financial sanctions-busting network to access hard currency.14 FDD’s Iran plan, building on years of sanctions work by our scholars, recommends numerous actions that the Biden administration could take, including in coordination with Congress.

The nuclear reality is stark: The regime has rapidly expanded its nuclear program since the election of President Biden. The bulk of the most dangerous steps, including enrichment to 20 percent and 60 percent, as well as the installation of hundreds of advanced centrifuges, production of uranium metal, and the ongoing construction of a new facility that could be used for nuclear enrichment, occurred after that date.15 According to estimates, Tehran could “break out” and produce four bombs’ worth of weapons-grade uranium within weeks.16

America’s Iran strategy thus needs a credible U.S. military threat, and a corresponding shift in the U.S. defense posture in the Middle East, to deter the regime in Iran from developing nuclear weapons. Washington also needs to ensure that the regime perceives the Israeli military option as credible and likely. The FDD plan offers numerous recommendations on how to do just that.

The American pressure campaign should also undermine the regime by strengthening the pro-democracy forces in Iran. It should target the regime’s soft underbelly: its massive corruption and human rights abuses, especially against women. As the recurring protests demonstrate, the gap between the ruled and the regime is expanding. Many Iranians no longer believe that the “reformists” can change the Islamic Republic from within. After the 2009 uprisings, Khamenei alluded to his regime as being “on the edge of a cliff.”17 President Biden should convey that America will help the Iranian people push it over that edge. FDD’s Iran plan offers numerous actionable recommendations on how to support the Iranian people’s efforts to achieve this objective.

To be sure, encouraging the collapse of a brutally repressive regime like the Islamic Republic of Iran will not be easy or predictable. It will require sustained U.S. pressure and a steely determination — perhaps over a period of years. Yet helping to free Iran remains a solution that Washington should not abjure merely because it is difficult. Ultimately, it remains the key to reducing instability in the region and advancing U.S. interests.

The Biden administration should present Iran with the choice between a new and better agreement and an unrelenting American pressure campaign, which includes the credible use of force. The nuclear issue likely will loom large for years to come. Disarmament demands should not require abandoning a campaign of pressure.

Washington does not need to have a public strategy to help collapse the clerical regime; Reagan did not have one for the USSR. Our political leaders, however, should underscore the inevitability of the fate of an ideologically, politically, and economically bankrupt regime that will end up on the “ash heap of history.”18 Reagan spoke that way about the Soviet Union in his famous 1982 Westminster speech. In 1983, he issued NSDD-75. Six years later, the Berlin Wall came down. Two years after that, the Soviet bloc collapsed.

Washington should intensify the pressure on the mullahs as Reagan did on the Soviets. We would be far better off without another dogged enemy armed with atomic weapons if we can possibly avoid it.

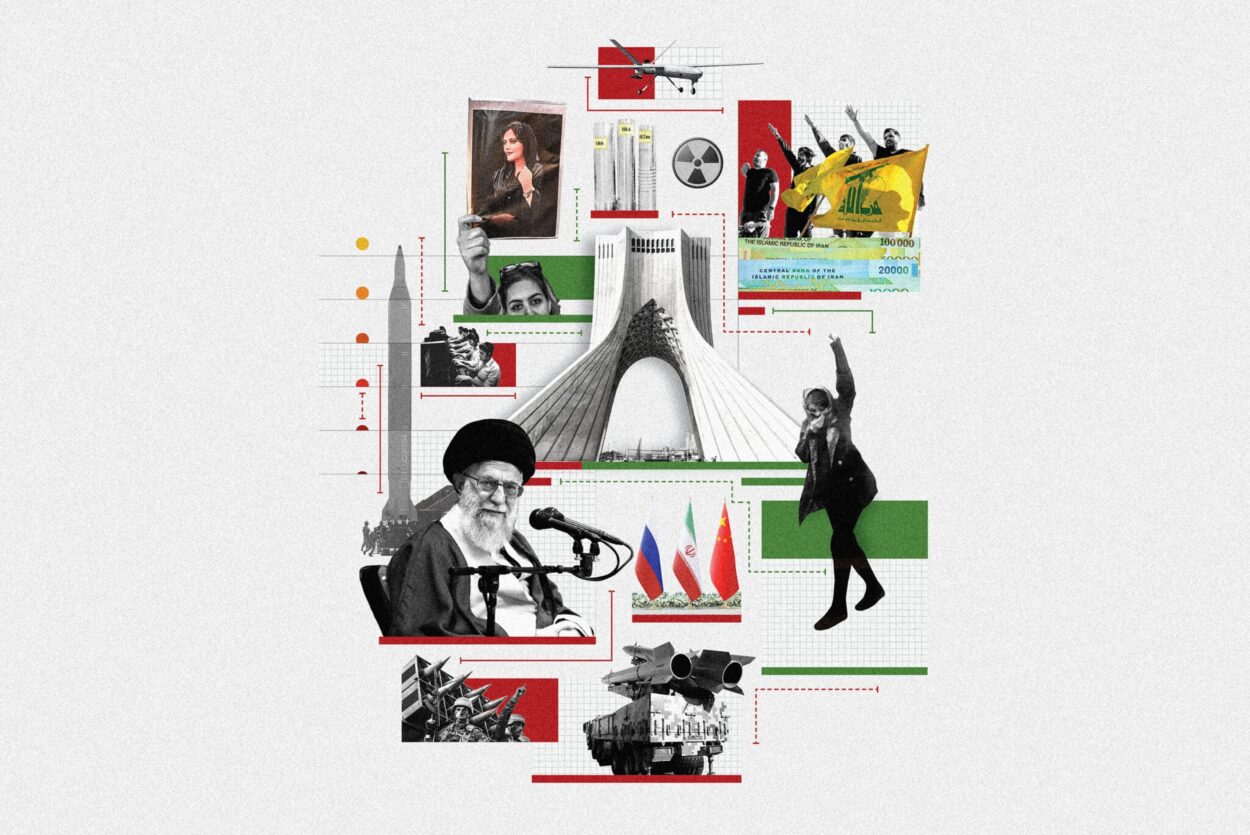

Illustration by Daniel Ackerman / FDD

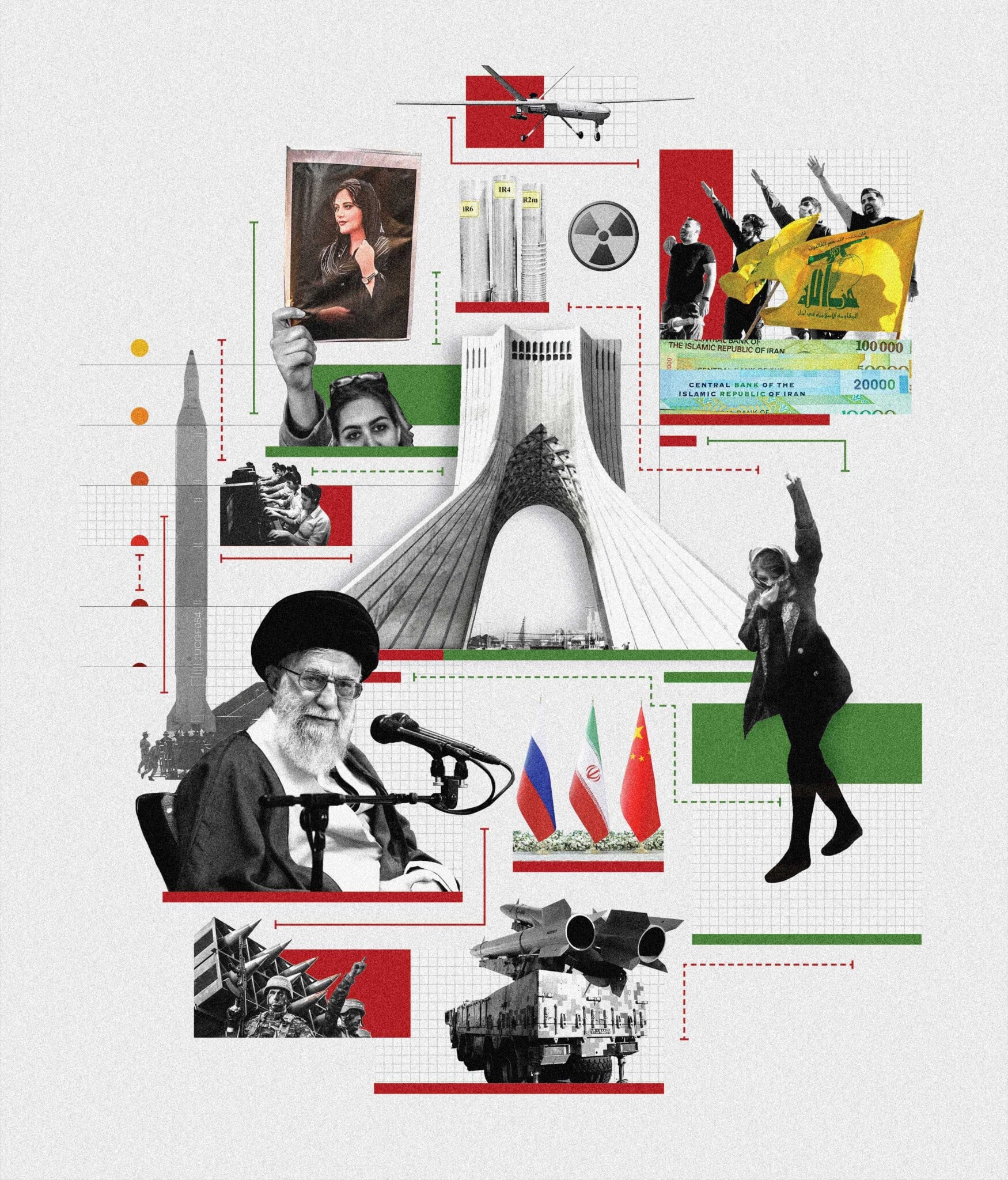

Illustration by Daniel Ackerman / FDD

Introduction

This memorandum’s recommendations are designed to constrain, deter, weaken, and over time reverse the Islamic Republic of Iran’s capacity and will to threaten the United States, our allies and interests, and the Iranian people.

Since January 2021, the U.S. has sought to revive and build upon the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear agreement. As of this writing, given the widening protest movement inside Iran and Tehran’s increasing military cooperation with Moscow, the prospects of a restored or new nuclear deal with Iran are greatly diminished.

This memorandum provides the Biden administration with a range of policy options to implement a Plan B strategy for Iran: intensive support for the Iranian people combined with decisive coercive and constraining pressure on the regime in Tehran.

Acronyms

| AIO | Aerospace Industries Organization |

| INL | Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs |

| CBI | Central Bank of Iran |

| DIO | Defense Industries Organization |

| DOE | Department of Energy |

| DHS | Department of Homeland Security |

| DOT | Department of Transportation |

| DEA | Drug Enforcement Administration |

| EIA | Energy Information Administration |

| EDBI | Export Development Bank of Iran |

| FATF | Financial Action Task Force |

| GAO | Government Accountability Office |

| GCC | Gulf Cooperation Council |

| ICE | Immigration and Customs Enforcement |

| ISR | intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance |

| IAEA | International Atomic Energy Agency |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

| IO | International Organization Affairs |

| ITER | International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor |

| IEI | Iran Electronics Industries |

| INKSNA | Iran, North Korea, Syria Nonproliferation Act |

| IRGC-AF | IRGC Aerospace Force |

| IRGC-AF SSJO | IRGC-AF Self-Sufficiency Jihad Organization |

| IRGC-QF | IRGC-Quds Force |

| IRGC RSSJO | IRGC Research and Self-Sufficiency Jihad Research Organization |

| IRIB | Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting |

| JCPOA | Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action |

| JOR | “Joint Operations Room” |

| KYCC | “Know Your Customer’s Customer” |

| PKK | Kurdistan Workers Party |

| LEF | Law Enforcement Force |

| LAF | Lebanese Armed Forces |

| MODAFL | Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistics |

| NDAA | National Defense Authorization Act |

| NEC | National Economic Council |

| NSC | National Security Council |

| OFAC | Office of Foreign Assets Control |

| SPND | Organization of Defensive Innovation and Research |

| PGMs | precision-guided munitions |

| PSI | Proliferation Security Initiative |

| RICO | Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act |

| SBIG | Shahid Bagheri Industrial Group |

| SHIG | Shahid Hemmat Industrial Group |

| SEC | Securities and Exchange Commission |

| SLVs | Space/Satellite-Launch Vehicles |

| USAGM | U.S. Agency for Global Media |

| WMD | weapons of mass destruction |

| WTO | World Trade Organization |

Recommendations

National Security Council (NSC)

Structure

- A senior NSC official, with support staff, should be designated coordinator for Iran sanctions implementation, with responsibility for overseeing implementation of the sanctions to improve coordination between departments and increase the sanctions’ effectiveness. This official should coordinate overall sanctions strategy and the public rollout of specific designations and other sanctions developments. The position could be expanded to coordinate all Iran policy and could then be renamed.

- The official should have the requisite rank (deputy assistant to the president or higher) to work directly with deputy- and under secretary-level officials in departments and agencies. The official should report directly to the national security advisor and deputy national security advisor.

- Individual departments and agencies would retain their current sanctions authorities, except that oil sanctions coordination could shift to this new NSC office, since oil sanctions in particular require a whole-of-government response. The State Department’s Bureau of Energy Resources does not have the technical expertise to assess oil market impacts as thoroughly and as accurately as does the Energy Information Administration (within the DOE). The State Department also has competing interests internally, and country and regional teams too frequently want to capitalize on oil sanctions waivers, either as quid pro quo leverage or to shield a country with which they work closely. There will be a need for maximum transparency and coordination across bilateral interactions, requiring the involvement of the national security advisor, the secretary of energy, the National Economic Council (NEC) director, Treasury, and/or the NEC staff’s senior energy officials, thus justifying NSC coordination.

Policies

The NSC should coordinate the following to increase pressure in the absence of a deal:

- Deploying Treasury and State officials to relevant countries to ensure compliance with escrow/special purpose account restrictions.

- Tasking the intelligence community with closely monitoring all Iran-China illicit trade and identifying all Chinese entities involved in such trade. This should be a standing item for NSC coordination meetings.

- Clearly informing the Chinese government from the first day of a sanctions continuation or resumption that the U.S. will enforce its sanctions on any entity involved in illicit purchases of oil, including state-owned enterprises.

- Ensuring the U.S. does not grant waivers enabling China to be paid in oil pursuant to upstream investment contracts with Iran. In 2019, the Trump administration considered “an arrangement that would allow China to import Iranian oil as payment in kind for sizable investments of the Chinese oil company Sinopec in an Iranian oil field.” 19 Such a “payback oil waiver” should not be allowed, since Chinese upstream investment should be deemed illicit and high-risk in the first place.

- Directing Treasury to prepare sanctions on Chinese firms when sufficient information is available on relevant violations. Admittedly, in some cases the intelligence benefits of continued collection on a sanctions evader may outweigh the benefits of enforcement. In addition to China, Iraq and Turkey should also be monitored for oil sanctions evasion. The U.S. should prioritize assisting Iraq to develop alternative sources of energy and seek an end to Iraq’s sanctions waiver as soon as possible.

- The U.S. should initiate or continue an NSPM-13 (National Security Presidential Memorandum) process to develop and approve an offensive cyber campaign plan for Iran.

Department of the Treasury

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)

- The U.S. should robustly enforce current sanctions, with an emphasis on targeting IRGC entities and individuals active in key sectors of Iran’s economy. The emphasis should be not only on targeting IRGC entities and individuals engaged in malign conduct but also on deterring international businesses from taking the risk of doing business with the IRGC. This should involve mapping IRGC networks in relevant sectors and running information campaigns designed to change the risk/reward calculus of thousands of private sector actions.

- The U.S. should increase awareness among Western companies of the risks of doing business with the IRGC through diplomatic meetings, public notices, conferences, hearings, legal action, and other mechanisms.

- The U.S. should impose and enforce new sanctions on market segments — including regime-tied businesses and customers — that are connected to the IRGC or are under its influence, including sectors not yet subject to penalties. These include existing mining, metallurgy, and construction sanctions and new sanctions targeting telecommunications (with clear exceptions and/or licenses to facilitate secure communications among protesters) and computer science firms as well as academic institutions that support the regime’s missile program. Enforcement of energy sector sanctions should be dramatically tightened while enforcement of automotive sector sanctions should increase as well given that sector’s support for the regime’s ballistic missile program.

- The U.S. should significantly increase the number of IRGC designations to target the thousands of IRGC front companies and persons, in particular those active in strategic sectors of Iran’s economy.

- Treasury’s ownership threshold for designation of an IRGC-owned or controlled entity should be lowered from 50 percent to 25 percent to conform with U.S. beneficial ownership rules.

- S. secondary sanctions should be applied to foreign companies doing business with entities owned or controlled by the IRGC (even when they are not specifically listed on the specially designated nationals list).

- The U.S. should designate sectors and supply chains of “IRGC influence.”

- The U.S. should promote the identification through watch lists (U.S. executive branch, congressional, and private) of IRGC entities that fall below the designation threshold.

- The U.S. should enforce and/or impose sanctions on the following entities under counterterrorism (E.O. 13224) authorities or nonproliferation (E.O. 13382) authorities, as appropriate:

- IRGC firms listed on the Tehran Stock Exchange (TSE);

- Iran Armed Forces firms on the TSE; and

- the TSE itself (for supporting companies owned or controlled by the IRGC and the Iran Armed Forces).

Hezbollah

- The U.S. should designate relevant financial institutions pursuant to the Hizballah International Financing Prevention Act of 201520 and use the Hizballah International Financing Prevention Amendments Act of 201821 to target Hezbollah’s global financial and economic networks, including in Latin America and Africa, and the foreign banks and companies supporting these networks.

- The U.S. should thoroughly review existing sanctions against Hezbollah, with special attention to Latin America and Africa, where Hezbollah is very active. Many sanctions are more than a decade old and require updates. This review will likely reveal additional illicit activities and sanctionable entities.

- Pursuant to Section 311 of the USA PATRIOT Act, the U.S. should designate as entities of “primary money laundering concern” relevant financial institutions and banking sectors used by Hezbollah financiers, including in hubs of illicit activity such as the Tri-Border Area.

- The U.S. should work with allies to blacklist corrupt officials who cooperate with Hezbollah. The U.S. can target such corrupt officials and their families under Section 7031 of the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2022,22 permanently barring them and their families from entry into the United States; under Executive Order 13318;23 under the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act;24 and under the Hizballah International Financing Prevention Amendments Act of 2018.25

- The U.S. should encourage and assist African and Latin American governments to strengthen their legal frameworks to investigate terrorist activities (including terror finance), particularly those related to Iran and the IRGC, as many governments still do not maintain terrorism lists.

- The U.S. Treasury should review Israel’s listings of companies that provide Hezbollah with material support for the production of precision-guided munitions (PGMs). Treasury should include those companies that meet the criteria on its Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN) list and wield maximum leverage to end their cooperation with Hezbollah. The companies listed by Israel include Moubayed for Lubricants SAL, Barakat Electro Mechanical & Trading co. SARL, and Toufaili General Trading (otherwise known as TCM Tfayli). Israel asserts that these companies provide Hezbollah with oil lubricants, machinery, and ventilation systems to facilitate the PGM project.26

- The U.S. should designate, under the Shields Act, persons involved in Hezbollah’s use of human shields.27 This should include persons responsible for building the human shield infrastructure in Lebanon (e.g., government officials, terror operatives, construction and insurance companies, banks, licensing authorities, and material providers).

Palestinian Terror Proxies

- The U.S. should impose sanctions on the Al-Nasser Salah al-Din Brigades, which is the third largest terror organization in the Gaza Strip but has yet to be sanctioned. Hamas and Islamic Jihad cooperate with approximately a dozen other militant factions that together comprise the “Joint Operations Room” (JOR) of the Palestinian militant factions. The Al-Nasser Salah al-Din Brigades is a major player in the JOR and has boasted about receiving military support from the regime in Tehran and its proxy Hezbollah.28 Furthermore, the Brigades have published evidence of their rocket strikes against civilians in Israel.29

- The U.S. should target Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and the Al-Nasser Salah al-Din Brigades with derivative designations (on those who provide material support or assistance to terrorist groups) to increase financial and political pressure.

- While Treasury sanctioned several Hamas companies and individuals in May 2022, others that generate revenue for Hamas remain unlisted.30 Sanctioning them could help reveal more of Hamas’ financial network, particularly in countries such as Turkey and Malaysia.

- The U.S. should designate, under the Shields Act, persons involved in human shields use by Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and other Palestinian terrorist organizations allied with Iran.31 This should include persons responsible for building the human shield infrastructure in the Palestinian territories (e.g., regime officials, terror operatives, construction and insurance companies, banks, licensing authorities, and material providers).

Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting

The United States designated the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) as a human rights abuser with the passage of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for fiscal year 2013, which required sanctions on the IRIB and its inclusion on the Office of Foreign Assets Control’s (OFAC) list of SDNs and blocked persons. Section 1248 of the Iran Freedom and Counter-Proliferation Act (passed as part of the 2013 NDAA) states, “The Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting has contributed to the infringement of individuals’ human rights by broadcasting forced televised confession and show trials.”32 The IRIB was also designated pursuant to E.O. 13628 in February 2013 for restricting or denying the free flow of information to or from the Iranian people. Next steps should include the following:

- The U.S. should continue designating IRIB officials, producers, news directors, reporters, writers, and anchors while encouraging allies to do the same.

- Treasury should review whether banks and corporate entities are providing the IRIB with material support and designate them, just as the U.S. sanctioned Ayandeh Bank in 2018 under E.O. 13846 for its role in “having materially assisted, sponsored, or provided financial, material, or technological support for, or goods or services to or in support of, IRIB.”33

- The U.S. should encourage and assist the International Telecommunications Union to issue additional condemnations of Iran for its violations of international telecommunications laws.

- The U.S. should encourage its European allies to direct telecommunications regulatory authorities in EU member states to revoke the IRIB’s licenses to operate. The United Kingdom’s national telecommunications regulator (the Office of Communications) revoked Press TV’s license in 2012 for its broadcasts of forced confessions.34 The telecommunications regulators in EU member states should follow the UK’s lead and revoke the IRIB’s license to operate and broadcast.

Telecommunications Sector

- The U.S. should designate telecommunications companies that are majority owned by the Government of Iran, the Supreme Leader, or the IRGC. These companies are complicit not only in human rights violations but also in executing Tehran’s illicit cyber campaigns. In addition to designating these telecommunications companies, the U.S. should expose and hold accountable Chinese telecommunications companies, including but not limited to Huawei, ZTE, and Tiandy, which continue to operate in Iran in violation of U.S. sanctions.35 Some of these Chinese companies reportedly sell technology to Iran that is used to surveil and oppress critics of the Islamic Republic.36

- The U.S. should issue licenses to provide surveillance-circumvention technology to Iranian dissidents. The U.S. should also deny export licenses for technology that can improve the Iranian regime’s ability to conduct malicious cyber intrusions against the U.S. and its allies, or to harass or censor Iranian dissidents.

Financial Sector

- U.S. officials should notify SWIFT stakeholders, including board member banks, that all Iranian banks on the SWIFT network must be disconnected. As of October 2022, there were at least 17 Iranian banks subject to sector-based sanctions under E.O. 13902 that had not been disconnected by SWIFT as they had not been designated in connection with the regime’s WMD proliferation, support for terrorism, or human rights abuses.37

- The U.S. should work to ensure that the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) maintains the mandatory countermeasures (steps members are urged to take) that it has re-imposed on Iran. The U.S. should ensure these countermeasures are maintained until Iran verifiably completes its “action plan,” the steps FATF has delineated for it to address its deficiencies. Maintaining FATF countermeasures on Iran will be even more important if a new Iran deal is agreed upon and implemented, since access to SWIFT will be dependent on FATF’s removing Iran from its blacklist.38 Until the action plan is satisfied, the U.S. should work to ensure Iran remains on this FATF blacklist.

- Congress should legislatively condition any lifting or weakening of Treasury’s designation of Iran as a “jurisdiction of primary money laundering concern,” pursuant to a USA PATRIOT Act Section 311 determination, on a presidential certification that Iran has verifiably ceased its support for terrorist organizations and is no longer a state sponsor of terrorism.39

- The U.S. should clarify through guidance, regulations, and legislation that international banks will be responsible for “Know Your Customer’s Customer” (KYCC) rules for Iran-related transactions, which require the banks to subject Iran-related transactions to the requisite level of scrutiny.

Regime Assets

- The U.S. should track family members of senior officials who study or work in the United States, Canada, or Europe to identify the sources of their overseas cash. Such family members are reputed to live lavishly while abroad.40 Tracking and publicizing their funding sources could embarrass the regime and help uncover unknown regime assets.

- The U.S. should publicly announce an “Iran Kleptocracy Initiative” to systematically expose the hidden assets of corrupt regime officials and specifically note that the U.S. will examine whether regime officials or designated persons are using family members to hide assets.

Financial Support Networks for Proxies and Allies

- The U.S. should weaken regime proxies and regional allies — particularly those designated as Foreign Terrorist Organizations and Specially Designated Global Terrorists — by strengthening or expanding related sanctions as appropriate. This should include sanctioning banks that provide services to them and otherwise targeting their funding sources.

Malign Activity

- The U.S. should expand efforts to block flights by the U.S.-designated Mahan Air to Europe and the Gulf. These efforts should include the use of secondary sanctions to systematically target ticketing agents and ground services operators as well as banks facilitating the airline’s payments for airport services. Mahan Air is currently designated under counterterrorism authorities for support to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force (IRGC-QF) as well as under a counterproliferation authority that targets weapons of mass destruction proliferators and their supporters. Treasury has already designated several sales agents for Mahan Air and penalized a freight forwarder for transactions involving Mahan Air.41

- The U.S. should impose and/or enforce sanctions against targeted entities involved with:

- Bandar Abbas Port and its operators;

- Bandar Imam Khomeini Port;

- Imam Khomenei Airport, Mehrabad Airport, and the Civil Aviation Organization of Iran (these designations should be under Syria-related sanctions);

- Iran Air for transporting weapons and fighters to support the IRGC, Hezbollah, and the Assad regime;

- regime-backed entities active in Syria; and

- the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) and the Export Development Bank of Iran (EDBI) (under Syria-related or other non-nuclear sanctions).

Human Rights Abusers

- The U.S. should sanction additional major human rights abusers and corrupt regime officials in Iran — particularly in the judiciary and the IRGC — pursuant to the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act; the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act; Executive Order 13553;42 and other authorities. To date, the Biden administration has sanctioned several key persons and entities involved in violently suppressing Iranian protests and in other human rights abuses, including the morality police and senior officials such as Minister of Intelligence Esmail Khatib and Deputy Commander of the Basij Salar Abnoush.43 Additional potential targets for designation include:

- Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei;

- Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi;

- Seyed Alireza Adyani, chief of the ideological-political office of the Islamic Republic’s police forces;

- Second Brigadier General Ali Azadi, chief of police forces in Kurdistan;

- Colonel Sayd Ali Safari, chief of police forces in Saqez;

- Colonel Salman Heidari, chief of police forces in Bukan;

- Colonel Abbas Abdi, chief of police forces in Diwan Dareh; and

- Colonel Mohammad Zaman Shalikar, chief of police in Babol, Mazandaran.

Ballistic Missiles

- The U.S. should encourage and assist foreign countries and companies to impede the Iranian regime’s ballistic missile program. This should be done through official outreach to industry and businesses (like Treasury’s outreach to foreign banks)44 in jurisdictions of concern for missile-technology procurement or broader Iran-related sanctions-busting. This outreach should raise awareness about regime proliferation practices as well as the risks of doing business with Iran.

- Treasury should lead a broad interagency policy and intelligence review aimed at identifying additional relevant companies, state-owned entities, and sectors of the Iranian economy that support Tehran’s ballistic missile capabilities and other long-range strike capabilities. This list should be shared with U.S. allies45 who possess relevant proliferation sanctions authorities, in order to coordinate maximum pressure.

- The U.S. should issue an executive order frontally addressing the regime’s missile/long-range strike capabilities that are not related to the delivery of weapons of mass destruction (WMD).46 This would do several things: give greater urgency to countering the evolving conventional missile and drone threat; streamline use of Executive Order 13382;47 and reduce reliance on Executive Order 13949,48 which addresses the regime’s conventional arms trade in general — rather than missiles and other long-range strike capacities — and focuses more on transfers and proliferation than on production and employment.49

- The U.S. should continue to expose networks involved in the regime’s procurement of proliferation-sensitive materials such as carbon fiber and maraging steel, missile or military-related components, and other key items for Tehran’s missile and nuclear programs.50 Wherever possible, Treasury should increase interagency cooperation with both the Commerce Department and the Department of Justice (DOJ) to fully deploy U.S. legal authorities against procurement and smuggling rings, especially in instances involving U.S.-origin equipment or technology.

- The U.S. should enforce and/or impose new sector-based sanctions targeting key nodes of the Iranian economy that support the regime’s ballistic missile program. These include existing sanctions like energy, petrochemical, metallurgy, mining, and construction and new sanctions targeting chemicals, electronics, telecommunications, and computer science.51

- The U.S. should designate key companies and research institutions associated with advancing regime missile capabilities in mobility, survivability, precision, maneuverability, and more. The regime’s missile program is growing in qualitative, not just quantitative ways, representing a fast-advancing threat for U.S. policy. One threat vector of particular concern is the regime’s progress on solid propellants,52 both for its shorter-range systems — which Iran is increasingly employing in military operations53 — and for its space/satellite-launch vehicles (SLVs), which could be a cover for the regime’s intercontinental ballistic missile program.

- The U.S. should continue to expose the Iran-North Korea missile relationship, in particular, cooperation on development of long-range missiles and associated engines. The Treasury Department imposed sanctions against regime defense contractors working with North Korea on such missiles in 2016.54 According to the UN’s panel of experts on North Korea sanctions, North Korea and Iran resumed cooperation on long-range missile development projects in 2020.55

- To strengthen the stigma of support for the regime’s long-range strike programs and to avoid the mass delisting of such military entities under a new nuclear deal, the U.S. should explore the applicability of terrorism sanctions pursuant to Executive Order 13224 to entities already subject to proliferation sanctions for supporting the regime’s missile, drone, and other long-range precision strike programs.56 This would ensure that if proliferation sanctions are lifted, these individuals and entities would remain designated under different authorities. Naturally, relevant evidence would need to be demonstrated. Similarly, the U.S. should explore the applicability of proliferation and terrorism sanctions to banks, businesses, persons, or governments which facilitate the transfer of these capabilities but are not yet subject to U.S. sanctions or are using shell companies or fronts to avoid detection and designation.

- The U.S. should increase the overall pace and scope of designations against subordinate entities and front companies that are part of the following elements of the regime’s military-industrial complex: Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistics (MODAFL), Defense Industries Organization (DIO), Aerospace Industries Organization (AIO), Shahid Bagheri Industrial Group (SBIG), Shahid Hemmat Industrial Group (SHIG), and Iran Electronics Industries (IEI). It is of critical importance to use counterproliferation authorities under Executive Order 13382 to target their affiliates or subordinates as well as companies engaging with those subordinates or affiliates. It should be communicated to America’s European partners, which are slated to delist the above entities by October 2023, that Washington is prepared to use punitive economic measures against any actor, including in Europe, transacting with these entities (although a snapback pursuant to United Nations Security Council Resolution 2231 would render this issue moot).

- The U.S. should increase targeting of the IRGC Aerospace Force (IRGC-AF), which is the guardian of the regime’s ballistic missile arsenal. Any Iranian or foreign entity that provides support for the IRGC-AF — including its Self-Sufficiency Jihad Organization (SSJO), the Al-Ghadir Missile Command, or the entire Guard Corps’ Research and Self-Sufficiency Jihad Organization (IRGC RSSJO) — should be sanctioned. Similarly, Treasury should explore sanctions against elements of the Artesh (national military) involved in the regime’s precision-strike program.

Cyberattackers

- The U.S. should expand cyber-related sanctions against Iran to target not only individuals involved in regime-backed cyberattacks and other malicious cyber activities but also the senior leaders who order attacks and the industries, companies, and research institutions that serve the regime’s cyber capabilities.57

- The U.S. should designate the regime’s Ministry of Information and Communications Technology and all its key officials in addition to already-designated former Minister Mohammad Javad Azari Jahromi 58and current Minister Eisa Zarepour.59 This ministry oversees the regulation and monitoring of Iran’s cyberspace and is complicit in regime-backed cyberattacks.60

- The U.S. should enhance collection and analysis of intelligence concerning the ways Iran has previously and would likely in the future deploy cyber-enabled economic warfare attacks against U.S. partners and allies in the Middle East. This would help Washington understand when Iran is likely to launch new cyberattacks on the homeland.

- The U.S. should cooperate closely with Israel’s cyber units in defending critical infrastructure in both countries from Iranian cyberattacks. The National Security Agency and Unit 8200 of the Israel Defense Forces should take the lead in identifying opportunities for offensive cyber operations to weaken regime infrastructure and support Iranian protesters.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

- The U.S. government should institute enhanced due diligence and disclosure requirements with regard to the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (jointly enforced by the SEC and the DOJ)61 for firms operating in Iran. Transparency International, a respected anti-corruption organization, ranks Iran as among the most corrupt countries in the world.62 One large international business has been repeatedly fined for bribing Iranian regime officials to secure contracts in Iran.63 Bribes paid in Iran risk subsidizing terrorist entities.

Department of State

IRGC, Hezbollah, and Quds Force

- The U.S. should press the EU, UK, Canada, and Australia to designate the IRGC as a terrorist organization in its entirety. The EU should also designate the “civilian” wing of Hezbollah. (The EU has already designated Hezbollah’s military wing as a terrorist organization.) The U.S. should also persuade allies in Latin America and Africa to list Hezbollah as a terrorist organization.

- The U.S. should deny visas to politicians, particularly those in Latin America and Africa, who facilitate Hezbollah’s illicit finance in their own jurisdictions.

- The U.S. should press allies to halt Iranian regime activity that utilizes diplomatic missions and private businesses to support terrorism, including the targeting of Iranian diaspora communities and other terrorist conduct by regime officials.

- The U.S. should develop and implement region-specific strategies to more effectively disrupt, degrade, and dismantle the Iranian regime’s terror network. For example, the U.S. should have specific strategies for Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia, including better information operations against the regime’s allies and potential allies in those regions.

- The U.S. should statutorily increase resources for the State Department’s “Rewards for Justice” program to target — in coordination with the DOJ — key Hezbollah and Quds Force officials operating outside Iran, with an emphasis on Latin America and Europe.64

IRGC Military Modernization

- To ensure the regional military balance of power remains in Washington’s favor, the U.S. must pursue a concerted effort to suppress the regime’s military modernization efforts. This should include the use of executive orders and legislation to expand sanctions designations and enforcement actions related to the regime’s trade in conventional weapons. Particular emphasis must be placed on preventing Tehran’s acquisition of more advanced fighter aircraft, air defense systems, armor, cruise and ballistic missiles, and anti-access/area-denial naval weapons platforms. Where feasible, such regime acquisitions should be interdicted.

- The U.S. should utilize both sanctions and interdiction to target Iran’s growing export of UAVs and other weapons systems to malign actors, including Russia, China, and the regime’s allies in the Middle East.

Ideological/Political Warfare Priorities (Human Rights/Democracy)

- The U.S. government should publicly state that it regards the Islamic Republic as illegitimate and call for free and fair elections.65

- The U.S. government should share appropriate intelligence with Iranian protesters to warn them about the regime’s security service deployments and inform them about Tehran’s weaknesses and strengths.

- The U.S. government should also — as it has done with Russia — rapidly declassify (when appropriate) and disseminate information on the regime’s plans, potential false flag operations, disinformation operations, and other activities so that Tehran must react rather than drive the narrative.

- The U.S. should support efforts to provide the Iranian people access to uncensored internet via satellite, in keeping with Treasury’s efforts to broaden the application of general licenses for such purposes.

- The U.S. should encourage and facilitate the deployment of terminals for the Starlink satellite internet service for use by Iranian protesters. Satellite internet can help Iranians regain internet access as the regime tightens its repression in cyberspace and doubles down on a national intranet. To hasten the deployment of Starlink terminals, Washington could establish a Free Internet Fund (or similarly named entity) under public-private auspices to offer Starlink financial support for an Iran-specific acquisition program.

- The administration should create an interagency team to ensure that Iranians get access to the necessary hardware, through smuggling or other means, so that technologies like Starlink can be utilized. The team should also help identify and contest the regime’s efforts, through disinformation and hacking, to mislead Iranians about the current operational status of Starlink and comparable tools.66

- The U.S. should ramp up its designations campaign that follows its recent designation of the morality police and select military commanders who have presided over Iran’s latest crackdown. These penalties, aimed at naming, shaming, and penalizing the Iranian people’s oppressors, could target the Law Enforcement Force (LEF), the Basij, and IRGC commanders at regional and local levels. Governors, governors-general, and a host of political and judicial officials complicit in the crackdown at the regional and national levels could also be designated, if appropriate. Policymakers can determine their culpability through open sources.

- The U.S. should broaden the scope of sanctions on the regime’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and on President Ebrahim Raisi, both of whom are already under sanctions but not for human rights violations. For example, Executive Order 13876 currently targets those in the Supreme Leader’s office or those appointed by the Supreme Leader to a political position. The administration should amend the order to integrate human rights sanctions into the order’s sanctions regime. It should also broaden human rights sanctions and apply them to defense and intelligence sectors of the economy, based on the regime’s record of human rights abuse. Washington should extend these sanctions to other pillars of the regime with a financial or institutional nexus to support for regime repression.

- The U.S. should use existing State Department authorities under a 2019 appropriations act to specifically prohibit the entry into the United States of the regime’s human rights violators and their families.67

- The U.S. should share actionable information about Iranian human rights abusers with its international partners that possess or are developing sanctions authorities. Washington should first focus on individuals on the Treasury Department’s blacklist in cases where relevant evidence exists of human rights violations. It should then broaden its focus to new targets. After that, the administration should commence a dialogue with international partners to persuade them to consider a visa ban against the same persons and their families. The net result would be a widening “no-go zone” for Iranian human rights violators and their families.

- The designation and accountability campaign should then be “multilateralized” against the IRGC, the LEF, regime officials, sanctions busters, censors, and others aiding the Islamic Republic’s repression machine. Canada’s recent sanctions against the morality police, as well as those by the EU and UK, are good examples of this, but the use of sanctions must expand to include all American partners with relevant capabilities.68

- Where there are instances of entities or persons subject to EU penalties who have not yet been targeted with State Department and Treasury Department authorities, the administration should rapidly close the transatlantic gap.

- The U.S. should prioritize sharing information with appropriate foreign law enforcement agencies and investigative judges that are, or are considering, pursuing charges against regime officials for human rights abuses.

- The U.S. should encourage and facilitate creating a labor strike fund to support the Iranian protest movement, financed by penalties and past asset forfeitures related to Iran, akin to the funds provided to Poland’s Solidarity Movement during the Cold War.69 This fund should support the efforts of Iranian workers to engage in labor strikes. It should also provide financial support to families of political prisoners and those who have lost breadwinners in current or past protests.

- In addition to pushing for the regime’s removal from, or censure in, international organizations, the U.S. should encourage allies to sever or downgrade their diplomatic relations with Iran.

- The U.S. should build on Iran’s ouster from the UN Commission on the Status of Women and expel or suspend Iran from other international organizations.

- The Biden administration should instruct U.S. delegations to walk out of international meetings when a regime official is speaking.

- The U.S. government should underscore that Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi’s 2021 election was a rigged process that was neither free nor fair.70 Hundreds of candidates were disqualified from running.71 The U.S. government should also emphasize that, given Raisi’s prominent role in Tehran’s execution of thousands of political dissidents in 1988,72 he deserves condemnation and prosecution in international fora.

- The U.S. should offer a clear vision of how its relations with Iran could change if Iran were to be more free and democratic.

- The U.S. government should condemn, prosecute, and designate all Iranian officials involved in the regime’s repeated efforts to kill on American soil Iranian dissidents, including Iranian American journalist Masih Alinejad, and former U.S. officials, including former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and former National Security Advisor John Bolton.73

- The U.S. government should repeatedly condemn the regime’s 1989 fatwa against author Salman Rushdie, point out that it remains in effect, and provide additional information to prove how the regime inspired the August 2022 assassination attempt against the author.74

- The U.S. should more broadly prohibit regime officials, and their immediate family members, from traveling to the United States. This should include barring President Raisi from future trips to New York to address the UN.

- Members of Congress and other U.S. officials should consider “adopting” high-profile Iranian dissidents and telling their stories publicly (as was done with Soviet-era refuseniks).

- The U.S. should encourage allied governments — including those of the EU and other democracies — to condemn Iranian human rights abuses more vociferously, including through parliamentary action as well as in trade negotiations and other fora.

- The U.S. should increase the Iranian and international public’s understanding of the depth and breadth of the regime’s corruption, including by encouraging increased attention to the corruption of the Supreme Leader’s holding company EIKO, the bonyads (charitable trusts), the IRGC, the clerical establishment, and other state and quasi-state entities.75 This can be done through U.S.-backed media channels but should not be limited to Voice of America (VOA) or Radio Farda.

- The U.S. should draw increased attention to Iran’s severe societal problems — including high unemployment (25 percent among young people), drug abuse, rampant prostitution, abuse of women and minorities, pollution, skyrocketing inflation, and corruption — and prevent the Iranian regime from distorting or concealing the realities.76

- The U.S. should draw increased attention to Iranian human rights abuses, including the regime’s high execution rate. In 2021, Iran’s executions per capita were second only to those of China, and in the first half of 2022, the number of executions in Iran roughly doubled over the same period the previous year.77 Senior U.S. officials should condemn abuses against dissidents by name and encourage condemnation of the regime by appropriate human rights fora. For example, top U.S. officials should regularly draw attention to the regime’s human rights abuses in their speeches, and the State Department should call for the release of all Iranian political prisoners, including the leaders of the Green Movement.

- The U.S. should publicize the regime’s persecution of minority communities.78

Ballistic Missile/WMD Procurement

- The U.S. should use State Department sanctions authorities — under Executive Order 13382; under the Iran, North Korea, Syria Nonproliferation Act (INKSNA); and under other nonproliferation sanctions and measures — to supplement existing SDN listings for entities that support the regime’s long-range strike capabilities, procurement, production, and proliferation. Since some authorities have lower thresholds for designation than others, an entity that may not meet the evidentiary standard for inclusion on the SDN list could be considered under other authorities.

- The U.S. should work with allies to expand membership in the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) to appropriate additional states — 107 had signed on to its principles as of August 2022.79 It should also work with existing members to develop and enhance legal authorities and coalitions for efforts to stop the spread of WMD and associated delivery technologies.80

- The U.S. government should create an interagency task force to expose, punish, deter, devalue, and defeat the evolving Iranian unmanned aerial threat, including the regime’s increasingly precise ballistic and cruise missiles and its use of drones as both WMD and non-WMD delivery vehicles.

- The U.S. government should actively enforce Executive Order 13949, which pertains to the regime’s conventional arms, and increase intelligence-sharing with law enforcement agencies (DOJ/FBI) to fight smuggling networks with a U.S. nexus where legal action may be taken.81

- The U.S. should enhance efforts to encourage and assist relevant countries to implement their export control and other international legal obligations relating to nuclear nonproliferation. Many governments in the Middle East have a weak record of implementing such obligations, including those required by UN Security Council Resolution 1540, which is binding on all UN member states.82

- The U.S. should vigorously expose sanctions violators through systematic “name and shame” campaigns. Sanctions violations reportedly continue to occur in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).83

- The U.S. should increase efforts to coordinate with allies on bilateral and multilateral sanctions and other measures against entities supporting the regime’s missile and nuclear programs.

- The U.S. should work with allied authorities to re-create Iran “warning lists” — like those the UK maintained prior to the JCPOA or those still retained by the Japanese Foreign Ministry — which are related to entities that may support regime proliferation activities. Unlike formal sanctions or designations, these lists serve as a warning to industries and companies that may engage with the target.

- The U.S. should encourage and assist the EU (and UK) to retain sanctions on Iranian missile and military-related entities found in Attachment 2 of Annex 2 of the JCPOA slated for de-listing in October 2023. At the same time, the U.S. should encourage the EU (and UK) to establish parity with earlier iterations of American sanctions on Iran’s missile program to include proliferation networks.84

- The U.S. should work with the UK, France, and Germany to trigger the snapback provision of UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 2231 to ensure the EU and UK do not delist various military entities supportive of Tehran’s missile program, such as MODAFL, AIO, DIO, IEI, SBIG, and SHIG, which are all scheduled to be delisted on Transition Day (October 2023) under the JCPOA and UNSCR 2231.85

Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Allies

The U.S. should more vigorously encourage and assist the GCC — particularly Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain — to do the following:

- Use oil as a weapon — particularly Saudi Arabia — to drive down Iranian energy-related hard-currency earnings (and undermine Russian military support to Iran).

- Reduce GCC business with Iran.

- Force key international companies to choose between doing business with important GCC countries or doing business with Iran. (The U.S. should share a list of pending deals with GCC countries and encourage them to put these foreign companies to this choice.)

- Impose sanctions on regime entities that finance terrorism and missile proliferation.Whether the snapback takes place or not, since the GCC countries (and Israel) are not parties to the JCPOA, nothing prohibits them from establishing their own sanctions lists and designating key governmental and commercial entities (including the CBI and the National Iranian Oil Company, or NIOC) that are engaged in financing terrorism or missile proliferation. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, (and Israel) could publish these sanctions lists and proactively contact large multinational banks to ensure their compliance programs take these sanctions into account. The Terrorist Financing Targeting Center can be used as a means to pursue this objective.86

Other Allies and Major Powers

- The U.S. should further expose the Iranian regime’s ties to terrorism and the drug trade. This includes where appropriate declassifying intelligence revealing the links between al-Qaeda and the regime’s security services.87 The U.S. should also facilitate exposure of IRGC and other Iranian involvement in trafficking drugs to Turkey, Europe, and the United States, as well as networks in Latin America and Africa.88

- The U.S., in cooperation with Israel, should declassify and publicize appropriate information on Iranian missile facilities across Syria and Lebanon to expose Tehran’s efforts to proliferate arms, including long-range strike weapons, across the Middle East.

China

- The U.S. should declare to Beijing, both privately and publicly, that Iran sanctions violations by China or Chinese entities will elicit a rigorous U.S. response. This includes resumption of “unofficial” Chinese purchases of Iranian oil with falsified identification from countries like Malaysia, the UAE, and Oman.89

- The U.S. should identify current and planned Chinese investments in Iran’s oil, natural gas, mining, petrochemical, transportation, telecommunications, and agricultural sectors for possible inclusion in future sanctions. When appropriate, the U.S. government should publicly disclose details about such Chinese investments, highlighting that they could lead to U.S. sanctions pressure, including export controls and additional licensing restrictions.

- The U.S. should expose Chinese culpability in the Iranian regime’s malign procurement pursuits, such as in cases where Chinese components have been included in Iranian weapons or missile systems or in cases where Chinese technology or know-how has meaningfully contributed to regime human rights violations.

Cyber Capacity-Building

- The U.S. should expand cyber capacity-building programs with partners and allies in the Middle East.90

- The U.S. should fund the U.S.-Israel Cybersecurity Cooperation Enhancement Act.91

- The U.S. should create in the Middle East an expanded version of the Assistance to Europe and Eurasia program,92 which supports cybersecurity efforts in Eastern Europe to improve incident response and remediation capabilities. Such a new program in the Middle East could train regional personnel on international cyberspace law, policy, and technical aspects of attribution of cyber incidents.

- The U.S. should leverage programs within the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) to enable regional partners to develop and implement more effective national laws, policies, and procedures to hold malign actors accountable.

- The U.S. should expand foreign military financing for cybersecurity capacity-building efforts.

- The U.S. should expand cybersecurity-specific funding within the Economic Support Fund and the Digital Connectivity and Cybersecurity Partnership.93

- The U.S. should replicate the successful USAID Ukraine cybersecurity programs with U.S. partners and allies in the Middle East.94

- The ambassador-at-large who leads the State Department’s new Bureau of Cyberspace and Digital Policy should conduct a multi-nation diplomatic visit to the Middle East.

U.S. Mission to the United Nations (USUN) and the State Department Bureau of International Organization Affairs (IO)

- The U.S. should work with the UK, France, and Germany to trigger the snapback provision of UNSCR 2231, thereby ending all JCPOA sunsets, restoring the UN arms embargo on Iran, keeping the missile embargo on Iran indefinitely, and dramatically increasing Iran’s political, strategic, and economic isolation. UNSCR 2231 requires that the triggering JCPOA participant state assert that Iran has engaged in “significant non-performance of commitments under the JCPOA.” The resolution then references “Iran’s statement that if” snapback occurs, “Iran will treat this as grounds to cease performing its commitments under the JCPOA.”95

- The U.S. should frequently introduce UNSCRs against Iran to force Russian and Chinese vetoes. This would showcase Iranian malign activities and place pressure on the Russia-China-Iran axis. Such resolutions should reference the regime’s human rights violations, citing the UN’s special rapporteur on human rights in Iran.

- The U.S. government should provide the UN’s special rapporteur on human rights in Iran with additional material reflecting the grave human rights violations occurring in Iran.

- The U.S. should instruct all U.S. representatives to the UN (including in New York and Geneva and U.S. diplomats at every UN agency) to wage diplomatic isolation campaigns against Iran, including by regularly introducing resolutions condemning Iran.

- The U.S. should reject Iranian attempts to join the World Trade Organization (WTO) and any other international bodies of which it is not currently a member.

- The U.S. State Department, U.S. Trade Representative, and other relevant actors should carefully monitor Iran’s efforts to join the WTO. Iran has observer status in the WTO and has completed the first step toward accession, but its accession has been put on hold.96 In April 2016, then Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif requested that the EU, which publicly supported Iran’s WTO bid, pressure the United States to permit Iran’s entry.97 Nonetheless, the process has been paused until a chair is named for the Working Party on Iran’s accession.98

- Iran seeks membership in the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) project, which is working to develop the world’s largest tokamak, an experimental device theoretically capable of conducting nuclear fusion to create a renewable, carbon-free energy source.99 In October 2018, the United States reportedly used its seat on ITER’s governing council to block Iran from joining.100 It should continue to do so to prevent nuclear knowledge transfers.

- The U.S. should pursue opportunities to suspend Iranian membership in international organizations wherever possible.

- The U.S. should aggressively expose Iranian missile and other arms exports, particularly exports prohibited by UNSCRs 1701 and 2216 (transfers to Lebanon and Yemen, respectively).

- The U.S. should spearhead passage of a UNSCR requiring all member states to counter the use of human shields. Even if such a resolution does not directly mention Iran and its proxies, it would create a powerful tool for countering the use of human shields by Iran as well as Hezbollah, Islamic Jihad, and other regime-backed groups.

- The U.S. should press the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to request inspections of Iranian military sites and sites of the SPND (the Iranian Organization of Defensive Innovation and Research) where evidence suggests nuclear weapons-related research and development may be present.101 Such inspections should investigate centrifuge manufacturing activities at military or other locations and verify whether Iran is conducting activities that could contribute to the design and development of a nuclear explosive device.

- The U.S. should push a resolution through the IAEA Board of Governors to find Iran in non-compliance with its obligations under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty for failing to declare nuclear material, sites, and activities and refer the matter to the UN Security Council.

- If a UNSCR 2231 snapback is implemented, the U.S. should work with its allies to restore the UN Panel of Experts — which was established by UNSCR 1929 and would come back into force following snapback — to publish independent assessments of the regime’s nuclear and dual-use procurement efforts and UN member states’ compliance.

Department of Defense (DOD)

- The U.S. should ensure that it has a credible military option for preventing Iranian acquisition of a nuclear bomb, including by ensuring that its military has the capacity to destroy the Iranian nuclear development program if necessary.

- The U.S. must convince Iran that it is willing and able to use decisive military force to prevent the regime from developing nuclear weapons. The U.S. should be ready to implement military contingencies if deterrence fails.102

- The U.S. should convey to Tehran that any gains to Iran from attacks on U.S. forces and interests or from the development of a nuclear weapon would be outweighed by the costs. In conveying this message, Washington should reject any distinction between the actions of Tehran and the actions of its terrorist proxies.103

- The U.S. should ensure that its force structure in the region is sufficiently capable and postured to impact the regime’s calculations across a wide variety of contingencies.104

- The U.S. should identify risks and develop plans to respond most effectively to specific steps Iran might take to destabilize the region, entrench and arm its proxy network, and increase the capability and lethality of its military. The objective of U.S. policy should be to preempt or impede regime aggression and to deter Tehran’s use of direct or indirect forces.

- The U.S. should help key partners in the region improve their ability to defend themselves from, and respond to, regime aggression and regime-backed aggression. A primary focus should be helping Israel build its capabilities to defend against attacks by Tehran’s terror proxies and to conduct a protracted campaign to destroy the regime’s nuclear program.

- The U.S. should create — through military exercises, planning, and intelligence-sharing — the most unified and capable American-Israeli-Arab coalition possible to counter aggression from Tehran and its terrorist proxies.105

Contingency Plans to Strengthen Deterrence

- The Pentagon should develop and implement a detailed plan combining information operations and military actions to demonstrate to Tehran that attacks by its proxies in Syria and Iraq on U.S. forces and interests will be treated as attacks by Tehran itself.

- Congress should ensure that the defense budget provides the Department of Defense (DOD) with adequate resources to: deter Iran from developing a nuclear weapon; rapidly execute military contingencies in the event deterrence fails; provide sufficient protection for U.S. personnel, bases, and embassies in the region; and project sufficient force to prompt Iran to de-escalate following a U.S. strike.

- The U.S. should improve U.S. and partner intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, missile defense, strike, and force-protection capabilities throughout the region, identifying opportunities to work more closely with regional partners to create a common threat assessment and more effective combined responses.

- Congress should require the DOD to identify ways to reduce the time between the planned delivery of each new major U.S. weapons system to Israel and the attainment of full operational capability. These methods could involve: 1) the allotment of training positions in U.S. schools; 2) the use of the Military Personnel Exchange Program to embed Israeli personnel in U.S. military units already employing a particular weapons system; 3) sending the weapons system to combined military exercises involving Israel; and 4) temporarily deploying U.S. units to Israel that possess the particular system to facilitate additional combined training. Sending U.S. units wielding certain systems to Israel for a few weeks or months prior to their delivery to Israel would provide the Pentagon an opportunity to hone dynamic force employment and the Air Force’s agile combat employment.106

- The U.S. should identify specific incremental steps Iran might take toward a nuclear bomb and delivery system and plan for how to respond to each such step. The U.S. intelligence community should be tasked with conducting a red-team assessment of gaps in U.S. collection and other vulnerabilities in detecting weaponization It should also establish decision points for military action that correspond to conduct (e.g., production of weapons-grade uranium) where its confidence level for detecting indications and warnings is the highest.

- The U.S. should expand the number of ground, air, and naval exercises that include the military forces of Israel, the United States, and Arab partners. The U.S. should seek to expand the complexity of these exercises over time to increase the readiness of the individual forces, their ability to operate together, and their deterrence against the Islamic Republic of Iran, including its terror proxies. The goal is to create the most unified and capable combined military coalition possible.107

- The U.S. should expand funding for “hunt forward operations” by U.S. Cyber Command and conduct missions with U.S. partners and allies in the region.108 These hunt forward operations not only strengthen allied or partner networks’ resilience against cyber threats, but also provide insights that inform the U.S. homeland defense.

Illicit Arms and Missile-related Transfers

- DOD should develop overt and covert plans to stop illicit arms and missile-related transfers by air, land, and sea. It should do this in coordination with State Department and USUN efforts to address the regime’s illicit arms and missile proliferation activities, including those prohibited by UNSCRs 1701 (arms transfers to Lebanon) and 2216 (arms transfers to Yemen). If a snapback pursuant to UNSCR 2231 is implemented, similar action should be taken to address such activities prohibited by all UNSCRs restored by triggering the snapback provision of 2231.109

- The U.S. should enhance intelligence-collection requirements, partnerships, and capabilities to detect Tehran’s illicit procurement efforts that violate international and national laws. The U.S. should also work with local authorities in jurisdictions where shipments or transshipments are taking place to detect, deter, and prevent them.

- The U.S. should, in order to oppose Tehran’s weapons proliferation, fully resource existing multinational constructs such as Combined Task Forces 150-153.110 Partner capability increases combined deterrence while reducing the burden on the U.S. military over time.111

- The U.S. should expand and fully resource NAVCENT’s Task Force 59, which can use unmanned assets to detect illicit maritime weapons transfers by the regime and other activities.112

Naval Activity

- The U.S. should decisively address Iranian naval activity that threatens U.S. ships.

- The U.S. should review current rules of engagement for dealing with unprofessional hostile Iranian naval activity to determine whether reforms are needed to better protect U.S. personnel and deter aggression.

- The U.S. should expand NAVCENT’s Task Force 59 while conveying to Tehran that there is no difference between attacks against manned and unmanned vessels owned or operated by the U.S. Navy.113

- The U.S should work with regional partners to increase the quantity and effectiveness of their patrols in and around critical chokepoints like the Strait of Hormuz and the Bab al-Mandeb.

- The U.S. should increase the number of anti-piracy missions in which the U.S. Navy engages in the CENTCOM Area of Responsibility.

- The U.S. should increase the number of exercises that simulate surface, aerial, and subsurface responses to attacks involving fast-attack craft and other vessels owned or operated by the IRGC Navy.

Counterproliferation

- The U.S. should ensure that the defense intelligence community places high priority on, and has maximal capacity to detect, any Iranian illicit procurement for its weapons programs, including nuclear, missile, military, and other dual-use procurements from China, North Korea, or other countries.114

- The U.S. must devote the intelligence resources necessary to fully understand the extent of the Iran-North Korea relationship, including cooperation on nuclear, ballistic and cruise missile, and conventional arms programs and any transfers of expertise, know-how, technology, equipment, and materials.115

- The U.S. should increase intelligence cooperation and joint counterproliferation operations with partners, including Israel and the Gulf states, regarding Iran’s nuclear and missile programs.116

Cyber

- The U.S. should enhance offensive cyber operation plans to disable or disrupt critical nuclear weapons development infrastructure. It should conduct operational preparation of the environment to enable these plans.

- The U.S. and its international partners have significant cyber capabilities that they should use to help Iranian protesters. These capabilities could be used to target the Iranian regime’s command and control systems, security forces, and massive bureaucracy, whose information and communications move through cloud and other internet and intranet networks.

- The U.S. should support labor strikes in Iran by using cyber capacities to disrupt the operations of key industries (e.g., the oil, gas, and financial sectors) and by creating a fund to provide financial support to laborers who go on strike. Oil strikes (coupled with market-supply and domestic-production issues) increased the power of protesters in the 1978-79 protests that toppled the monarchy in Iran.117

U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM)

- The U.S. should reestablish a medium-wave broadcasting capacity so that Iranians can listen to Radio Farda and VOA in their cars. Internet and television broadcasts can be blocked much more effectively than can medium-wave radio, which could be a cost-effective tool for the United States.

- Networks of the U.S. Agency for Global Media, including Radio Free Europe’s Radio Farda and Voice of America’s Persian service, should have the resources and mission to provide comprehensive reporting and analysis of internal protests, turmoil, repression, corruption, and the regime’s links to regional destabilization.

- USAGM broadcast content for Iran should prioritize:

- fact-checking statements made by regime officials and providing the Iranian people with information to counter propaganda;

- reporting on the regime’s illicit activities outside its borders, including in Syria and Yemen, and the amount of money these efforts are costing the Iranian people;

- reporting on corruption inside the regime and the IRGC;

- reporting on the hypocrisy of regime officials who preach hatred against the U.S. and the West but send their families to the U.S. or Europe for school, vacations, or long-term stays;

- reporting on independent (non-regime affiliated) political prisoners and prisoners of conscience, including interviews with their families; and

- reporting on pro-U.S., anti-regime figures inside Iran rather than on purported reformists tied to the Islamic Republic who are anti-U.S.

- USAGM should enhance the management and content development of its services.

- USAGM should more effectively counter regime efforts to block access to these services and their websites.

Department of Commerce

- The U.S. should increase operations against Tehran’s attempts to procure sensitive dual-use items. This includes preventing, deterring, and dismantling the regime’s procurement networks.