January 27, 2020 | Monograph

Occupied Elsewhere

Selective Policies on Occupations, Protracted Conflicts, and Territorial Disputes

January 27, 2020 | Monograph

Occupied Elsewhere

Selective Policies on Occupations, Protracted Conflicts, and Territorial Disputes

Introduction

Setting policies toward territories involved in protracted conflicts poses an ongoing challenge for governments, companies, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Since there are multiple zones of disputed territories and occupation around the globe, setting policy toward one conflict raises the question of whether similar policies will be enacted toward others. Where different policies are implemented, the question arises: On what principle or toward what goal are the differences based?

Recently, for example, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) decided goods entering the European Union that are produced in Jewish settlements in the West Bank must be clearly designated as such.1 At the same time, however, neither the ECJ nor the European Union have enacted similar policies on goods from other zones of occupation, such as Nagorno-Karabakh or Abkhazia. The U.S. administration swiftly criticized the ECJ decision as discriminatory since it only applies to Israel.2 Yet, at the same time, U.S. customs policy on goods imports from other territories is also inconsistent: U.S. Customs and Border Protection has explicit guidelines that goods imported from the West Bank must be labelled as such, while goods that enter the United States from other occupied zones, such as Nagorno-Karabakh, encounter no customs interference.

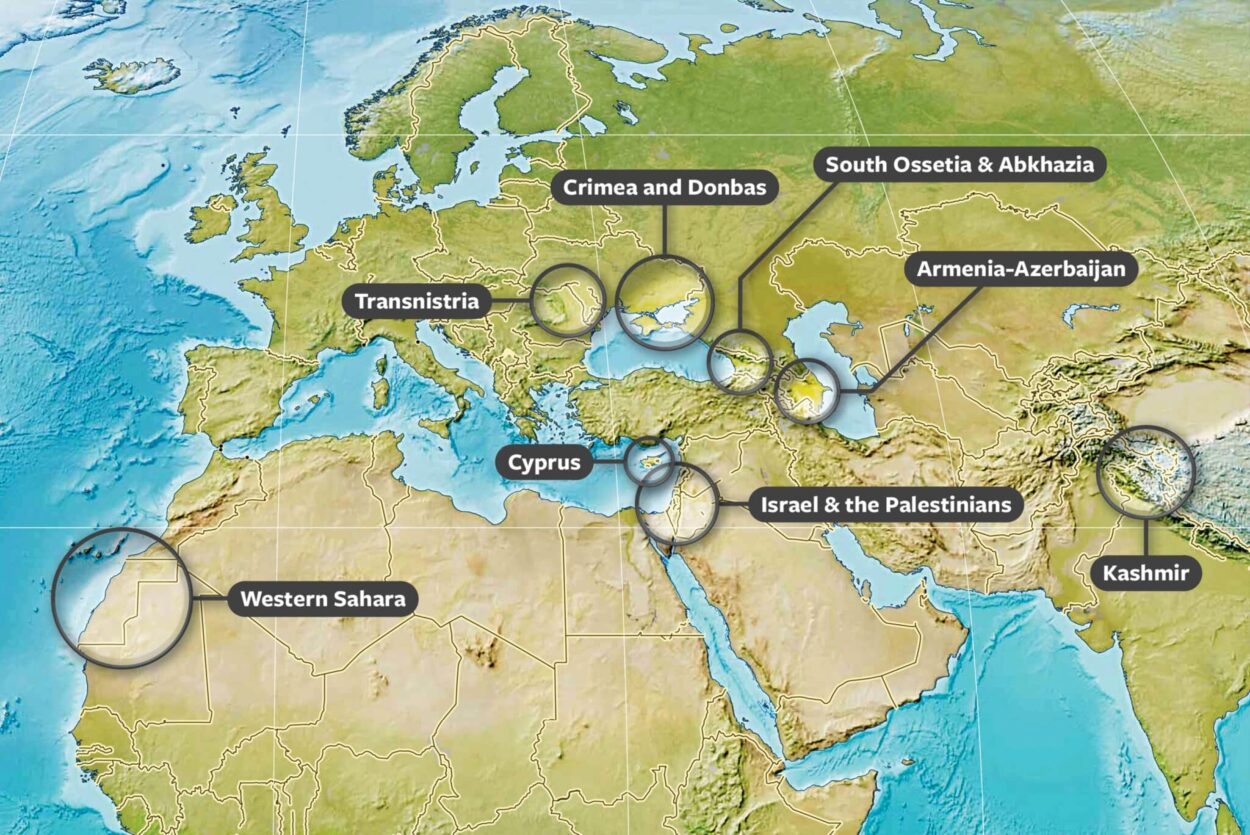

Territorial conflicts have existed throughout history. But the establishment of the United Nations, whose core principles include the inviolability of borders and the inadmissibility of the use of force to change them, led to the proliferation of protracted conflicts. Previously, sustained control over territory led to eventual acceptance of the prevailing power’s claims to sovereignty. Today, the United Nations prevents recognition of such claims but remains largely incapable of influencing the status quo, leaving territories in an enduring twilight zone. Such territories include, but are not limited to: Crimea, Donbas, Northern Cyprus, the West Bank, Kashmir, The Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict, South Ossetia, Abkhazia, Transnistria, and Western Sahara.3

The problem is not simply that the United Nations, United States, European Union, private corporations, and NGOs act in a highly inconsistent manner. It is that their policies are selective and often reveal biases that underscore deeper problems in the international system. For example, Russia occupies territories the United States and European Union recognize as parts of Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova, yet Crimea is the only Russian-occupied territory subject to Western sanctions. By contrast, products from Russian-controlled Transnistria enter the United States as products of Moldova, and the European Union allows Transnistria to enjoy the benefits of a trade agreement with Moldova. The United States and European Union demand specific labeling of goods produced in Jewish settlements in the West Bank and prohibit them from being labeled Israeli products. Yet products from Nagorno-Karabakh – which the United States and European Union recognize as part of Azerbaijan – freely enter Western markets labeled as products of Armenia.

Today, several occupying powers try to mask their control by setting up proxy regimes, such as the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) or similar entities in Transnistria and Nagorno-Karabakh. While these proxies do not secure international recognition, the fiction of their autonomy benefits the occupier. By contrast, countries that acknowledge their direct role in a territorial dispute tend to face greater external pressure than those that exercise control by proxy.

Some territorial disputes have prompted the forced expulsion or wartime flight of the pre-conflict population. A related issue is the extent to which the occupier has allowed or encouraged its own citizens to become settlers. While one might expect the international system to hold less favorable policies toward occupiers that drive out residents and build settlements, this is not the case. Armenia expelled the Azerbaijani population of Nagorno-Karabakh, yet the United States and European Union have been very lenient toward Armenia. They have also been lenient toward Morocco, which built a 1,700-mile long barrier to protect settled areas of Western Sahara and imported hundreds of thousands of settlers there. Against this backdrop, the constant pressure to limit Israeli settlement in the West Bank is the exception, not the rule.

This pressure is even more difficult to grasp given that Israel’s settlement projects in the West Bank consist of newly built houses. In most other conflict zones, such as Northern Cyprus and Nagorno-Karabakh, settlers gained access to the homes of former residents.

This study aims to provide decision makers in government as well as in the private sector with the means to recognize double standards. Such standards not only create confusion and reveal biases, but also constitute a business and legal risk. New guidelines for making consistent policy choices are therefore sorely needed.

Illustration by Daniel Ackerman/FDD; Map: CIA World Factbook Archive

Historical Background

The following is a survey of the history of several protracted conflicts: Crimea and Donbas, Cyprus, Israel and the Palestinian territories, Kashmir, the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict, South Ossetia and Abkhazia, Transnistria, and Western Sahara.

Crimea and Donbas

In 1954, the Soviet Union transferred the Crimean province from the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic to its Ukrainian counterpart. That mattered little during the Soviet period, but it meant that upon the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia controlled only a very narrow shoreline on the Black Sea – between Abkhazia and Crimea, with its main Black Sea naval base, in Sevastopol, in another country’s territory. In January 1992, Russian leaders challenged the legitimacy of this arrangement, pointing to procedural irregularities as well as the province’s ethnic Russian majority. The issue cooled after a 1997 treaty that secured Russia’s control of the Sevastopol base. But following the Orange Revolution of 2004, which brought the pro-Western Viktor Yushchenko to power in Ukraine, the Crimea issue heated up again, exacerbated by Russian fears of a possible NATO expansion eastward to include Georgia and Ukraine. The tenure of pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovich from 2009 to 2014 enabled Russia to renegotiate a long-term agreement that secured basing rights for its Black Sea fleet until 2042.4

The “Euromaidan” revolution of 2013-2014 brought matters to a head again. The unrest demonstrated to Moscow that its strategic influence over Ukraine was imperiled. This prompted Moscow to move to annex Crimea outright in early 2014. Russia then sought to establish a Donetsk People’s Republic and a Luhansk People’s Republic in eastern Ukraine on the model of the secessionist republics in the Caucasus and Moldova. Unlike in Crimea, however, the Ukrainian people fought back, leading to a stalemate that continues today.

In response to Moscow’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, Washington and Brussels imposed sanctions on Russia that remain in place today. Nevertheless, Russia’s utilization of proxies in Eastern Ukraine has successfully shielded Moscow from more severe punishment for its direct military intervention on another state’s territory.

Cyprus

The United Kingdom administered Cyprus from 1878 until 1960, during which time there was growing popular demand among the island’s Greek majority for unification with Greece, a process they called enosis. Ethnic Greeks accounted for 74 to 80 percent of the island’s population during this period, with ethnic Turks making up 15 to 20 percent. As demands for enosis grew, the Turkish community responded by advocating taksim, or partition, for fear that unification with Greece would lead to the expulsion of Turks, as had happened in Crete in the early twentieth century. An armed campaign for enosis followed, which led to the death of nearly 400 British soldiers.

In 1960, Cyprus gained independence under a constitution that provided for joint governance – a Greek president, a Turkish vice president, and a government and parliament elected by communal balloting, with a ratio of seven Greeks to three Turks. The United Kingdom, Greece, and Turkey were “Guarantor Powers” over the new state. However, the power-sharing system broke down in 1963, leading to inter-communal fighting and inconclusive UN mediation. The situation escalated following a 1967 military coup in Greece, which led to a short military standoff between Greece and Turkey over Cyprus.5

In 1974, a military coup in Cyprus instigated by the Greek junta prompted a Turkish invasion. This led to the Turkish occupation of over a third of the island and the displacement of over 200,000 Cypriots, as the island’s patchwork of Greek and Turkish areas gave way to an ethnic division between a Greek south and a Turkish north.

In 1976, Turkey created the Turkish Federated State of Cyprus (TFSC), which would purportedly form part of a future federal Cyprus following a peace agreement. The TFSC was based on the Turkish Cypriot administration created in the 1960s; since 1963, the official Cypriot government had been entirely Greek Cypriot, prompting the Turkish Cypriots to build their own administrative structures. On this basis, the TFSC was set up both as the de facto administration under Turkish occupation and as a diplomatic bid for equal status between two communities if Cyprus were to be reunited. The TFSC, however, did not formally secede from Cyprus, and thus it was the Turkish military occupation, not the declaration of that entity, that garnered international opprobrium.

The Greek-controlled Cypriot government, meanwhile, continued to represent the island diplomatically, and in 1983 the Turkish Cypriots unilaterally declared independence. The Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus is today recognized by only the Republic of Turkey and remains internationally isolated.

UN-led negotiations have since sought to resolve the conflict on the basis of a “bi-zonal, bi-communal federation,” a model also embraced by the European Union.6 The process of EU accession on the part of Cyprus proved a catalyzer for further negotiations from 2002 onward, as UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan personally took a leadership role in negotiations. The “Annan Plan,” which called for a loose federation of two states, was put to a referendum in April 2004.

However, rather than making Cyprus’ accession contingent on its approval of the peace plan, in May 2004 the European Union decided under Greek pressure to accept Cyprus to the European Union. This essentially gave Greek Cypriots a choice between entering the European Union as the island’s sole representative and submitting to a new power-sharing agreement with the Turkish Cypriots, with the latter requiring acceptance of the demographic effects of Turkish immigration in the north. Predictably, the Greek Cypriot leadership urged voters to reject the agreement, which they did by a large margin. Turkish Cypriots supported it by an equally large one, but this had little impact: Cyprus entered the European Union with an unresolved conflict on its territory and a significant Turkish military presence on its soil.

The Cyprus dispute has regained geopolitical importance as a result of discoveries of natural gas in the Eastern Mediterranean and a more assertive Turkish policy. The Greek Cypriot government has aligned with Greece, Israel, and Egypt to extract natural gas. Turkey, however, rejects Nicosia’s right to enter into any energy agreements before the dispute is resolved. Moreover, Ankara claims ownership of Turkey’s entire continental shelf, including waters considered by the European Union and United States to belong to Cyprus. Turkey has intervened to stop Cypriot vessels from drilling in the Cypriot sector of the sea and has deployed its own drilling vessels in offshore waters considered by Europe as Cypriot.

Israel and the Palestinian Territories

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict dates back to the end of World War I, when Great Britain took control of the area following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire. At the time, the area was populated by both Arabs and Jews, with a strong Arab majority.7 Under the British Mandate, the number of Jews grew, especially in the 1930s and 1940s, with many fleeing from the Holocaust during World War II. On November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution to partition the territory into two independent states – one Arab and one Jewish, with Jerusalem under international rule.8

The Jews in Palestine accepted the plan, but the Arabs in Palestine and neighboring countries opposed it fiercely. While the Israeli-Palestinian conflict began as unorganized Arab attacks on the Jews, after Israel’s Declaration of Independence on May 14, 1948, five Arab countries invaded Israel with the goal of eradicating it.9 The 1948 war resulted in Israel’s retention of most of the land designated to it under the UN Partition Plan and an additional 5,000 square kilometers.10 At the same time, more than 10,000 Jews living in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip were driven out or killed, and the Jordanian army – assisted by Iraqi forces in the West Bank and by the Egyptian army in the Gaza Strip – captured about a dozen Jewish communities.11

The remaining territories designated for a future Palestinian state were conquered by Egypt (the Gaza Strip) and Jordan (the West Bank and East Jerusalem). Jerusalem was divided between Israeli forces in the West and Jordanian forces in the East. Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians fled or were forced from their homes.12 However, many Arabs remained in their homes and became Israeli citizens.13

Following the war, Arab governments persecuted their Jewish communities, leading hundreds of thousands of Jews from Egypt, Yemen, Morocco, Iraq, Libya, and Syria to flee or be evicted – many to Israel. Neither the United Nations nor any other international organizations accorded the Jews refugee status. By contrast, after the 1948 war, the United Nations established a special agency dedicated to the Arab Palestinian refugees, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA).14 UNRWA initially responded to the needs of approximately 750,000 Palestine refugees. Today, some five million Palestinian claim refugee status due to an UNRWA policy of conferring that status on descendants of the original refugees.15

In the June 1967 war, Israel launched a preemptive attack against its belligerent neighbors, ultimately winning control of East Jerusalem, the West Bank, the Golan Heights, the Gaza Strip, and the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula. After the war, Israel annexed East Jerusalem, making the Arab population permanent residents and eligible for citizenship.16 Israel still occupies the West Bank, in accordance with a division of sovereignties between Israel and the Palestinian Authority, as agreed upon in the 1995 Oslo Accords.17 Over the past 50 years, Israel has built settlements in the territories it controlled since 1967. Today, approximately 415,000 Jews live in the West Bank and 215,000 in East Jerusalem.18

After the 1967 war, Israel established the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories, which implements civilian policy in the West Bank (and in Gaza Strip, prior to Israel’s withdrawal).19 An Israeli Civil Administration also operates in the West Bank, charged with implementing Israel’s civil policy in the territory. The Civil Administration consists of 22 government office sites located throughout the territory. Within this framework, executive officers maintain communication with local Palestinian residents, Israeli settlement representatives, and international organizations.20

The main governmental body in charge of planning, developing, and expanding settlements is the Settlement Division of the World Zionist Organization, in conjunction with the Israeli Prime Minister’s Office.21 The budget of the Settlement Division is funded directly by the Israeli government.22

Other government bodies involved in settlements in the West Bank include the Ministry of Construction and Housing, which finances the infrastructure and public buildings in the West Bank.23 The ministry also finances the Civil Administration in Judea and Samaria, a military body that implements Israel’s civil policy in the West Bank24 and is responsible for the designation of land eligible for Israeli settlement construction. The Israeli Ministry of Defense is responsible for issuing permits for building settlements in the territories.25 Finally, some indirect government funding provides support for settlers. For instance, funds allocated to the Immigrant Absorption Ministry to facilitate the immigration of the Jewish diaspora to Israel are used by immigrants that settle in the territories.26

In 1993, Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization signed the Oslo Accords.27 The goal was to facilitate an eventual Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank and Gaza Strip, and to establish a Palestinian Authority for self-government for an interim period until the establishment of a permanent arrangement.28

The Oslo Accords divided authority over the West Bank into three areas – A, B, and C.29 Israel continued to exercise full civil and security control in Area C. In Area A, where most of the Palestinian population resides, the Palestinian Authority assumed full responsibility for civil and security control. In Area B, the Palestinian Authority assumed civil responsibility as well as responsibility for public order of the Palestinians, while Israel maintained responsibility for the security of the Israelis living there.

In 2004, U.S. President George W. Bush and Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon exchanged letters as part of efforts to broker peace between Israel and the Palestinians. These efforts led Sharon to order Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from the Gaza Strip in 2005.30 The letters also included an understanding between the two leaders that for security reasons, Israel would not make a full withdraw to pre-1967 lines along the West Bank.31

Even as his understanding with Bush indicated Israel would maintain control over parts of the West Bank, Sharon directed the Ministry of Justice to conduct a study on unauthorized settlements there. The report identified unauthorized settlements and outposts32 that violated criteria established by the Israeli government (15 settlements and outposts were on land privately owned by Palestinians).33

Today, the official Palestinian position calls for recognition of their rights, including the right of refugees to return to the former homes of refugees from the 1948-1949 war.34 Israel rejects the Palestinian “right of return” but keeps the door open to negotiations. In recent years, negotiations have not been fruitful.

Kashmir

When Great Britain announced following World War II that it would leave India, it became clear that a united India would be impossible in light of tensions between the Hindu majority and the large Muslim minority in British India. During the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir faced pressure to join both India and Pakistan – a dilemma, since the state had a Muslim majority but a Hindu ruler, Maharajah Hari Singh.35

For a time, the Maharajah refused to accede to either ahead of partition. Many in the state desired independence rather than accession to either India or Pakistan. But amidst growing unrest and fears of a popular rebellion by the Muslim majority, the Maharajah signed an instrument of accession to India in October 1947. The British governor-general, Earl Louis Mountbatten, accepted this conditionally, pending a plebiscite confirming the will of the people. But Kashmir’s accession to India prompted an invasion from Pakistan, spearheaded by Pashtun tribesmen. The ensuing 1947-48 war ended with a territorial division, with India controlling more than half of Kashmir’s territory and more than two-thirds of its population – including the densely populated areas of Jammu and the Kashmir valley.

Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir (IJK) was incorporated into India as a state with a special status defined by Article 370 of the Indian constitution. Unlike other Indian states, the State of Jammu and Kashmir had its own constitution and flag as well as considerable self-rule. In fact, Indian law did not apply to the state unless ratified by the Legislative Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir. India’s federal responsibilities were limited to defense and foreign affairs, with IJK maintaining self-rule in other matters. As a result, for example, only natives were allowed to own property in the state.

UN mediation in 1948 envisaged withdrawal by both Pakistani and Indian forces, after which a plebiscite would determine the will of the states’ people. However, due to disagreements over both the conditions for the withdrawal of forces and the modalities of a public vote, nothing was ever implemented. India viewed a plebiscite only as a vote that would confirm Kashmir’s accession, and rejected the notion that such a plebiscite could include the options of accession to Pakistan or Kashmiri independence. But after the 1971 war in which Bangladesh seceded from Pakistan, India and Pakistan in 1972 signed the Simla Agreement. Because this agreement provided that the two states would “settle their differences … through bilateral negotiations,” India has since claimed the Kashmir issue is a purely bilateral issue between the two countries, and rejects UN mediation.

While Hindu nationalists have long argued that Article 370 was temporary and should be considered lapsed after the Constituent Assembly of IJK dissolved in 1957, the Indian Supreme Court reiterated – as recently as in 2018 – that the article “acquired permanent status through years of existence, making its abrogation impossible.”36

Periodic fighting occurred in the Siachen glacier from 1984 to 2003. In parallel, Kashmiri unrest grew in the 1980s following a rise in Kashmiri nationalism and Indian repression, leading in 1989 to a long and violent insurgency against Indian rule, heavily supported by Pakistan. While the insurgency was initially secular and nationalist, led by the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front, Pakistani training and support for Islamist insurgent groups led the insurgency to shift in a more religious direction. The conflict is today no closer to a resolution than it was at its inception. Meanwhile, the construction in the 1980s of the Karakorum highway linking China and Pakistan – now expanded into the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor – has only added to the region’s strategic importance.37

In August 2019, following his re-election, the government of India’s Hindu nationalist Prime Minister Narendra Modi fulfilled a longstanding campaign promise to abrogate Article 370. New Delhi also demoted IJK from a State to Union Territory and divided it in two – making the Ladakh area a separate Union Territory. This move was accompanied by a surge in troop presence; the arrest of Kashmiri leaders, including two former chief ministers; a curfew; and a near-total blackout of communications.38 The abrogation of Article 370 has been appealed to the Indian Supreme Court.39

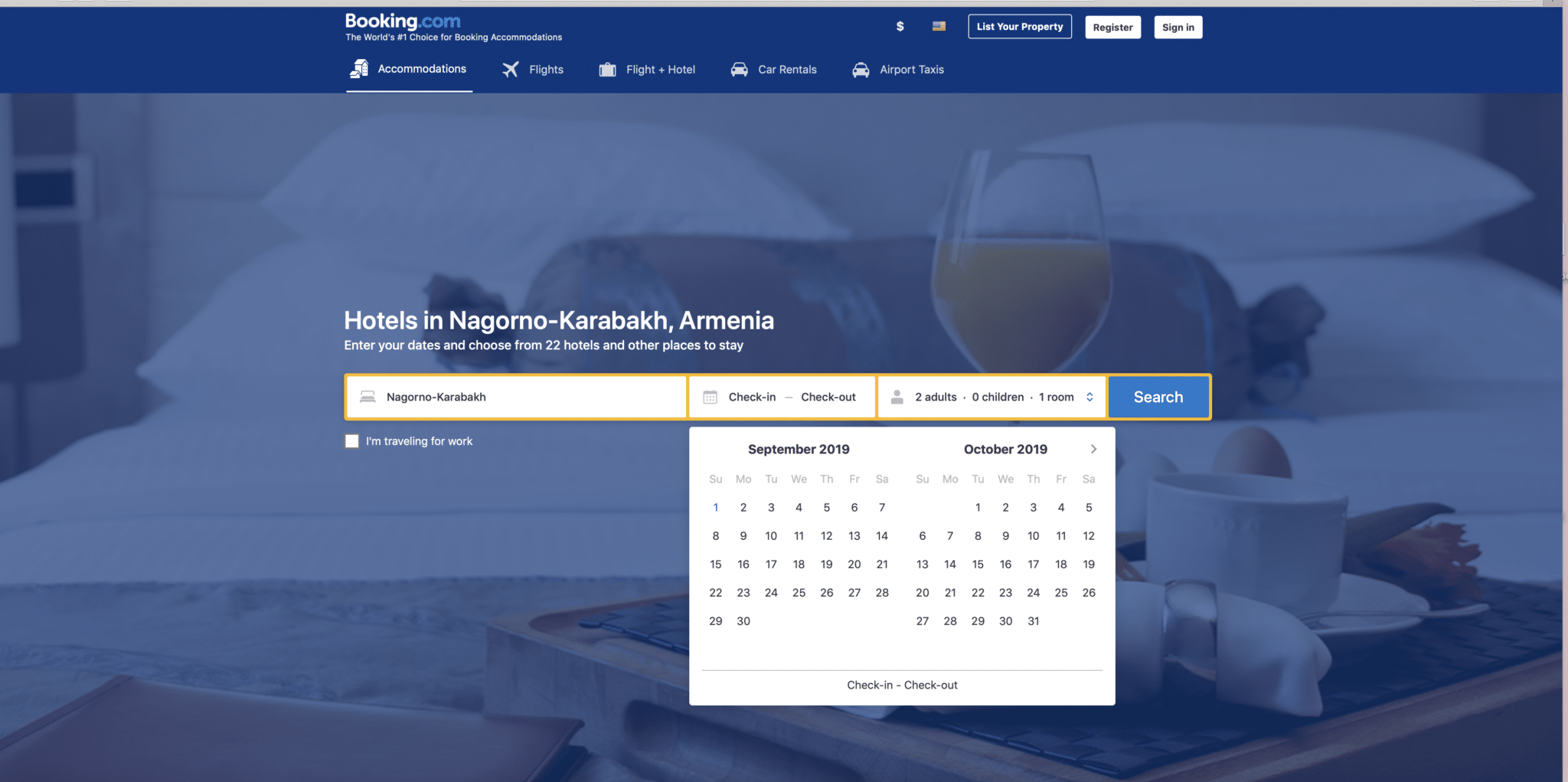

The Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict

The war between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the Nagorno-Karabakh region was one of the most lethal post-Soviet conflicts. It led to close to 30,000 deaths, created over a million refugees, and left the region economically shattered for years after the independence of the two states.40

Amid the weakening of central power in Moscow and the widening of political participation in the Soviet Union in the mid-1980s, the status of Nagorno-Karabakh became an issue of open conflict between Armenians and Azerbaijanis in the Soviet Union. While legally part of Soviet Azerbaijan, the Nagorno-Karabakh region was populated during the Soviet period by an ethnic Armenian majority. Moscow defined the region as an Autonomous Region within Soviet Azerbaijan. A movement of Armenian intellectuals known as the Karabakh Committee began openly petitioning the Soviet authorities in Moscow in 1987 for the transfer of control of Nagorno-Karabakh to Soviet Armenia. In 1987 and 1988, mass demonstrations took place in Yerevan in support of unification between Soviet Armenia and the region of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Unification with Nagorno-Karabakh became an important mobilizing factor for the Armenian independence movement in the late 1980s and an important political issue for Levon Ter-Petrossian, who emerged as Armenia’s first post-Soviet leader. Ethno-political mobilization in Armenia led to a rapid rise in ethnic tensions between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, spurring efforts by Armenian activists in late 1987 to force Azerbaijanis to leave their homes in rural Armenia. This led to violent ethnic clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis in Nagorno-Karabakh and elsewhere in Armenia and Azerbaijan, resulting in the flight and expulsion of approximately 250,000 ethnic Azerbaijanis from Armenia and some 250,000 ethnic Armenians from Azerbaijan at the end of the Soviet period.

After the Soviet collapse in late 1991, a full war erupted between newly independent Armenia and Azerbaijan. The Republic of Armenia aimed to capture Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding territories, especially those that could create a geographic link between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia.41 Russian forces took part in certain battles, stoking the conflict. The conflict saw close to 30,000 people killed and over 700,000 Azerbaijanis uprooted from their homes. According to Serzh Sarkisian, who commanded the Armenian forces during the war and later became the country’s president, Armenia employed a deliberate policy of mass killing to cause the civilian Azerbaijani population to flee.42

In 1994, both sides signed a Russia-brokered ceasefire leaving Armenia in control of the Nagorno-Karabakh region and seven surrounding administrative districts of Azerbaijan. Today, due to the forced eviction of the ethnic Azerbaijanis, Nagorno-Karabakh and the surrounding regions are populated almost exclusively by ethnic Armenians. Many parts of the occupied territories are largely depopulated.43

Nagorno-Karabakh is recognized as part of the Republic of Azerbaijan by almost all of the international community, including the United States. Yerevan formally maintains that Nagorno-Karabakh is separate from Armenia proper. Yet Armenia has not recognized Nagorno-Karabakh as a state. Nor has it formally annexed Nagorno-Karabakh. Yerevan is deterred from formal annexation or recognition since Azerbaijan would consider such a move a casus belli.44 Moreover, Armenia refrains from annexation to circumvent international responsibility for its occupation of Azerbaijani territories and for the displaced persons it expelled. In addition, by not formally annexing Nagorno-Karabakh, Armenia can continue to engage in an internationally led negotiation process, which lessens the likelihood of war, without having to make concessions. The main conflict resolution mechanism is led by the Minsk Group of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), comprising official representatives from the United States, Russia, and France. Despite frequent high-level meetings, the peace process has not yielded concrete results.

Today, the situation on the line of contact and the Armenia-Azerbaijan border is tense, with an average of over a dozen soldiers killed each year. From time to time, the conflict flares up into full battles. The last major flare-up occurred in April 2016, known as the “Four-Day War,” which led to over 200 deaths.

In 1993, the UN Security Council adopted four resolutions related to the conflict, which condemn ethnic cleansing and the occupation of Azerbaijani territory, calling on “occupying forces” to withdraw from recently conquered regions of Azerbaijan. However, one of the resolutions used the term “local Armenian forces,” a formulation that intentionally ignores widespread evidence of Yerevan’s direct participation in the hostilities.45 This formula was adopted in part at the insistence of Russia, a veto-wielding permanent member of the Security Council. Indeed, Armenian military units serve along the line of contact between the occupied territories and Azerbaijan’s military forces. The official website of Armenia’s Ministry of Defense acknowledges that the country’s soldiers fought and died in Nagorno-Karabakh and still serve on the front lines of the conflict.46 Illustrative of the fact that forces of Armenia control the occupied territories is that the son of the current prime minister of Armenia is currently serving his compulsory military service in the occupied regions contingent to Nagorno-Karabakh.47

South Ossetia and Abkhazia

Georgia stood out in the Soviet Union’s ethno-federal system as the only republic aside from Russia to have three autonomous entities in its territory. Of these, Abkhazia was an autonomous republic, indicating a higher level of self-government, while South Ossetia had the lower status of an autonomous province.48 Conflict initially arose with the development of a national independence movement in Georgia. Tbilisi’s drive for independence encouraged mobilization of Abkhaz and Ossetians to remain in the multi-ethnic Soviet Union.49

Moscow capitalized upon these feelings and supported the two movements as a tool to prevent Georgian independence from the Soviet Union. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, open conflict between Tbilisi and the breakaway regions broke out in 1991. Russia brokered a cease-fire in South Ossetia in June 1992, which it enforced with a Russian-led peacekeeping mission. The next month, Abkhazia declared independence, an event that prompted disorganized Georgian militias to stage an armed attempt to recapture the territory. With the support of Russian armed forces and North Caucasian volunteers, Abkhazia repelled the attack. In October 1993, a Russian-brokered cease-fire again yielded a Russian peacekeeping mission, this time under UN observation.

Russian-led negotiations over the following decade proved inconclusive not least because conflict resolution did not appear to be in Russia’s interest, something that became clear following Vladimir Putin’s rise to power in 1999. When the reformist government of Mikheil Saakashvili took power in Georgia in 2003, it sought to alter the status quo in the two conflict zones and called for international mediation to replace what it perceived to be Russia’s biased role.

Tensions eventually escalated until Russia staged military strikes in 2007 and 2008, including a rocket attack on a Georgian radar installation near South Ossetia, a helicopter attack on Georgian positions in Abkhazia, the downing of a Georgian drone, and the insertion of Russian engineering troops to build a railway across Abkhazia. This escalation, and Georgian reactions to it, culminated in Russia’s invasion of Georgia in early August 2008. As a result, Moscow asserted direct military control over both territories and recognized their independence – recognition that only thinly masks its direct control over both governments. That said, Moscow’s control is considerably greater in South Ossetia, which some analysts equate to a Russian military base. Abkhazia, by contrast, has sought to maintain some autonomy from Moscow.

As in the case of Nagorno-Karabakh, there is a clear international non-recognition policy toward Abkhazia and South Ossetia. After Russia recognized their independence, the United States and European Union successfully pressured most countries not to follow suit. Only Venezuela, Nicaragua, Nauru, and Syria have done so. Most importantly, no former Soviet state did so, despite immense Russian pressure.

Initially, Russia failed to shield itself from sanctions as the result of its 2008 invasion of Georgia. Despite its effort to escape responsibility by recognizing the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, Russia was hit with international sanctions for its refusal to implement the terms of a cease-fire agreement negotiated by French President Nicolas Sarkozy. These sanctions were lifted some months later following the international financial crisis.

Transnistria

Unlike Nagorno-Karabakh, South Ossetia, and Abkhazia, Transnistria was not an autonomous territory in the Soviet period. However, it was separated geographically from the rest of Moldova by the Nistru River. Moreover, it was host to a Soviet military garrison, the 14th Soviet Army. It also had a Slavic majority, with more Ukrainians than Russians, which together narrowly outnumbered ethnic Moldovans in the area.50

Toward the end of the Soviet period, conflict arose as anti-Soviet sentiment in Moldova accompanied growing support for unification with Romania, something that neither the Soviet leadership nor the Slavic population of Transnistria supported. In response, activists in Transnistria established the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Socialist Republic (PMR) in October 1990. By early 1992, with support from Soviet military trainers and weapons from the 14th Soviet Army, the PMR commanded a force over 10,000.

Military conflict escalated in the spring of 1992, when Moldova was admitted to the United Nations and PMR forces resisted Moldovan efforts to assert control of the country. The conflict ended with a Moldovan defeat at the hands of the superior forces based in Transnistria. A July 1992 cease-fire imposed by Russia established a peacekeeping mission similar to that in South Ossetia – dominated by Russian forces but including Moldovan and PMR components and controlled by a Russian-led Joint Control Commission (JCC). Ukraine, which borders the PMR, has had observers in the JCC since 1998, and OSCE representatives attend its meetings.

Unlike the conflicts in the South Caucasus, the Transnistria conflict was shorter and less ethnopolitical in nature. Relations between communities on the two sides of the river continued following the cease-fire, meaning that economic and cultural ties continue. Negotiations to resolve the conflict were long led by Russia. Most notably, Russia proposed the 2003 Kozak Memorandum, which sought to establish an asymmetric federal state that would essentially provide Transnistria, a Russian proxy with less than 15 percent of Moldova’s population, with considerable veto powers and extensive representation far beyond its population share. Following sizable demonstrations in Moldova against a plan that would diminish the country’s sovereignty, the memorandum was rejected.

From 2005 onward, in part due to Romania’s accession to the European Union, Brussels began to take interest in Moldova. In 2010, German Chancellor Angela Merkel proposed to Russian President Dmitry Medvedev to make the Transnistria conflict a test case of EU-Russian cooperation – with the upside for Moscow being the creation of an EU-Russia Committee with considerable influence on European security. In spite of the considerable benefits to Russia, Moscow abandoned the initiative shortly after Putin returned to the presidency in 2012.51

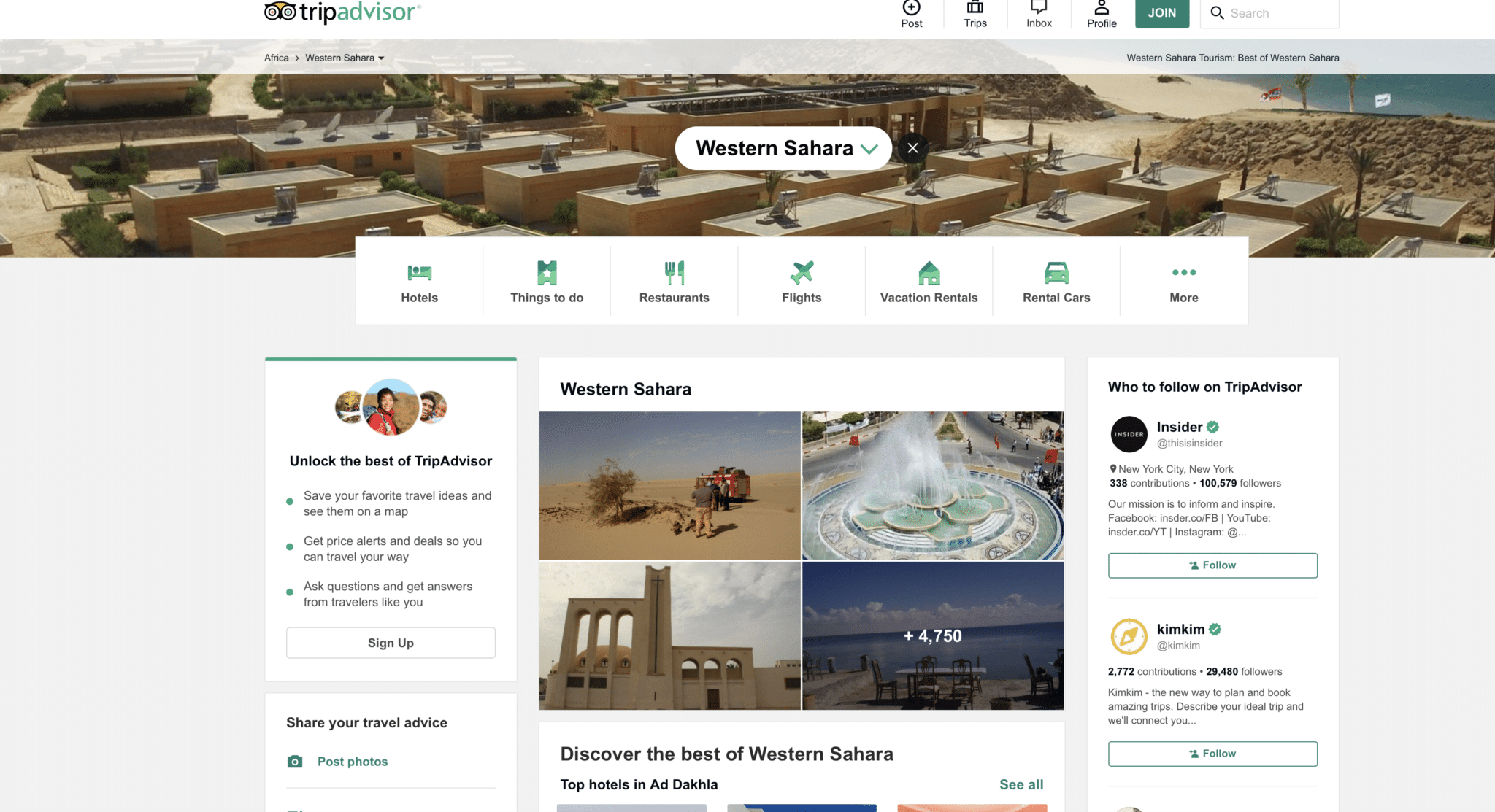

Western Sahara

Western Sahara was a Spanish colony until 1975. When Morocco gained independence in 1956, however, it claimed sovereignty over the territory and prevailed upon the United Nations to include the territory among those that should be decolonized. Mauritania also made claims to part of the territory. Facing domestic challenges from socialist activists as well as elements of his own military, Moroccan King Hassan during the early 1970s wielded the Sahara issue as a potent tool to bolster national unity and support for his rule.52

Western Sahara was one of the last African territories to remain under colonial control following the massive wave of decolonization in the 1960s. By 1970, only several Portuguese colonies as well as Djibouti, Namibia, and Western Sahara remained. Morocco actively pushed for decolonization, and Spain’s withdrawal in 1975 prompted Morocco and Mauritania to conclude an agreement with Madrid that allowed them to administer Western Sahara. This led to fierce resistance by the Sahrawi Arab tribes that inhabited the territory and wanted full independence. The Polisario Front (Frente Popular de Liberación de Saguía el Hamra y Río de Oro) emerged in 1973, first as an organization for resistance against Spanish colonialism. It turned its sights on Morocco, and proclaimed the establishment of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) in 1976. Mauritania relinquished its claims and recognized the SADR in 1979, leading to a break in its relations with Morocco, which annexed the areas previously claimed by Nouakchott.

The low-intensity armed conflict that followed prompted Morocco to assert control over the more economically viable western portions of the territory. Aided by Algerian support and training, however, the Polisario Front denied Morocco control over the largely desert hinterlands, and a stalemate ensued after Moroccan troops built a 1,700-mile sand barrier, or Berm, in the 1980s. A cease-fire negotiated by the United Nations in 1991 provided for a referendum. It was never held, however, as the parties disagreed on the question to be asked and on the population eligible to vote, among other issues. Morocco has offered autonomy for Western Sahara but rejects the option of independence.

Internationally, some 35 states recognize the SADR, and an additional 40 support the right of self-determination for the Sahrawi people. The SADR has been a member of the African Union since 1982. The European Union is split but generally supports a peace process that will lead to Sahrawi self-determination. Some EU states, however, such as France and several central European states, lean toward Morocco’s position. The United States does not formally have a policy on the conflict, although both the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations supported Morocco’s offer of autonomy to Western Sahara while furnishing Morocco with extensive military aid that bolstered Rabat’s control over the region. The Obama administration was ambiguous about the issue, indicating weaker support for Morocco’s claim than its predecessors.53 The Trump administration has yet to take a position.

International Legal Situation

International law is not easy to apply consistently to protracted conflicts, in part because of the varying circumstances surrounding their initiation, not to mention the status quo ante. The territories below had a diverse array of pre-conflict legal statuses, followed by an equally diverse array of statuses during and after the conflicts in question. For example, Kashmir and Western Sahara were European colonial possessions that became parts of India and Morocco, respectively. The West Bank spent 19 years under Jordanian occupation before Israel took control. Some occupiers have created proxy entities, such as those in South Ossetia and Nagorno-Karabakh, whose purpose is to enable the occupier to evade legal responsibility and condemnation.

How Territory was taken:Another state:

Non-state actor/undetermined status:

Mixed:

|

While useful for the occupier, proxies create a new international security challenge. First, they complicate conflict resolution, since the true occupying powers often do not engage in negotiations to resolve the underlying conflict. Second, because the de facto sovereign is not held accountable for law enforcement, they can become major centers of illicit activity, such as the trafficking of drugs and counterfeit goods, money laundering, human trafficking, and sanctions evasion.54

Means of Control:Annexation:

Accept International Law obligations as occupying force:

Proxies:

|

Case Studies

Israel and the Palestinians

Throughout most of the period that Israel has controlled the West Bank and Gaza Strip, it has taken on the legal obligations of an occupying force. Following the Six-Day War, the Israeli government declared the West Bank and Gaza Strip to be areas under belligerent occupation,55 according to the term’s definition under international law.56 The laws of belligerent occupation demand that a military government act to maintain the local law that prevailed on the eve of the conflict. Accordingly, the Israeli military commander of the territories issued a proclamation stating that pre-war laws would remain in force.57 The proclamation also stated, “[A]ll powers of government, legislation, appointment and administration regarding the area or its inhabitants shall be vested in [the military commander of the area] alone and shall be exercised by [the military commander of the area] or by any person appointed for such purpose by [him] or acting on [his] behalf.”

While it accepts the responsibilities of belligerent occupation, Israel does not define itself as an as occupying power pursuant to the Fourth Geneva Convention.58 The Israeli government maintains that the Convention does not apply, since Israel took control of the West Bank and Gaza from other occupying powers, not from a legitimate sovereign. This distinction is significant because Article 49 of the Geneva Convention prohibits the transfer of civilian populations into the territory in question, which Israel has done through the creation of settlements.59

At the same time, Israel voluntary observes the humanitarian rules of the Fourth Geneva Convention.60 Thus, Israel has applied the principles of Israeli administrative law to the use of its governing authority in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. According to former Chief Justice of Israel’s Supreme Court Aharon Barak, “Every Israeli soldier carries, in his pack, the provisions of public international law regarding the laws of war and the basic provisions of Israeli administrative law.”61

Israel’s Supreme Court has emphasized that the actions of the Israeli military commander in the territories are subject to judicial review. In addition, the Court has granted the Palestinians the right to petition Israeli courts even though they are not citizens of Israel.62 Thus, through judicial review and in response to Palestinian petitions, the military commander is subject to public international law.63

As a result of the 1993 Oslo Accords, Israel now shares responsibility with the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank, although it continues to apply the principles articulated by Barak. In 2005, Israel withdrew from Gaza, ending its occupation there. In short, the Israeli government took full legal responsibility for the territories it controlled, until it either shared control with another entity or withdrew its forces.

India and Pakistan in Jammu and Kashmir

The British created the princely state of Kashmir in the mid-19th century. Following the end of British rule in 1947, the ruler of Kashmir chose accession to India, not Pakistan, which resulted in a war between the two, and Kashmir’s enduring division.

The federal government in New Delhi granted substantial autonomy to what became known as Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir, while retaining responsibility for defense and foreign affairs. On the other side of the Line of Control, Pakistan cloaked its occupation by establishing a nominally self-governing state, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, which has its own flag, capital, government, parliament, and supreme court.64 The territory has an almost exclusively Muslim population, as the Hindu population fled to Jammu during the 1947 war.

India has faced persistent challenges to its rule, in part because the population of IJK is roughly two-thirds Muslim, of which a large majority support independent statehood, with a minority preferring accession to Pakistan. Non-Muslims are generally supportive of India.65 This state of affairs has changed little since 1947, leading New Delhi to systematically subvert the democratic institutions of IJK and impose its control over the state. One Indian-appointed governor recalled, “Chief Ministers of the State had been nominees of Delhi. Their appointment to that post was legitimized by the holding of farcical and totally rigged elections.”66

This heavy-handed approach has led to violent opposition, often backed by Pakistan, to which New Delhi responded by further tightening control, including by imposing martial law in 1990. Only by sending in several hundred thousand troops and paramilitary forces was India able to maintain control.67 Tensions rose once again in August 2019, after Prime Minister Narenda Modi repealed Article 370 of the Indian constitution, which provides Jammu and Kashmir with the autonomy it has enjoyed since partition. 68

Morocco in Western Sahara

When Spain withdrew from its colony of Western Sahara in 1975, it agreed to let Morocco move in. This led to fierce resistance by Sahrawi Arab tribes, which established the Polisario Front in 1973 to oppose Spanish rule. While Morocco never faced sanctions, in 1976 the Polisario Front proclaimed the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), which now enjoys recognition by over 35 countries, along with membership in the Organization of African Unity. There is considerable international support for the SADR, which is prominent in Western Europe and parts of Latin America.

The relative weakness of Rabat’s position stems in part from a miscalculation. Upon the decolonization of Western Sahara, Morocco appealed to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), claiming “immemorial possession” of the territory prior to colonial rule. But the ICJ disagreed, finding the territory and its inhabitants were a separate territory with a right to self-determination. Morocco moved in anyway, but cannot undo the ICJ’s finding against it. Still, Morocco has tacit support for its position from Washington and several EU states, despite the massive settlement program it implemented in Western Sahara and the building of a 1,700-mile long artificial ridge separating the areas it controls from those held by the Polisario Front.

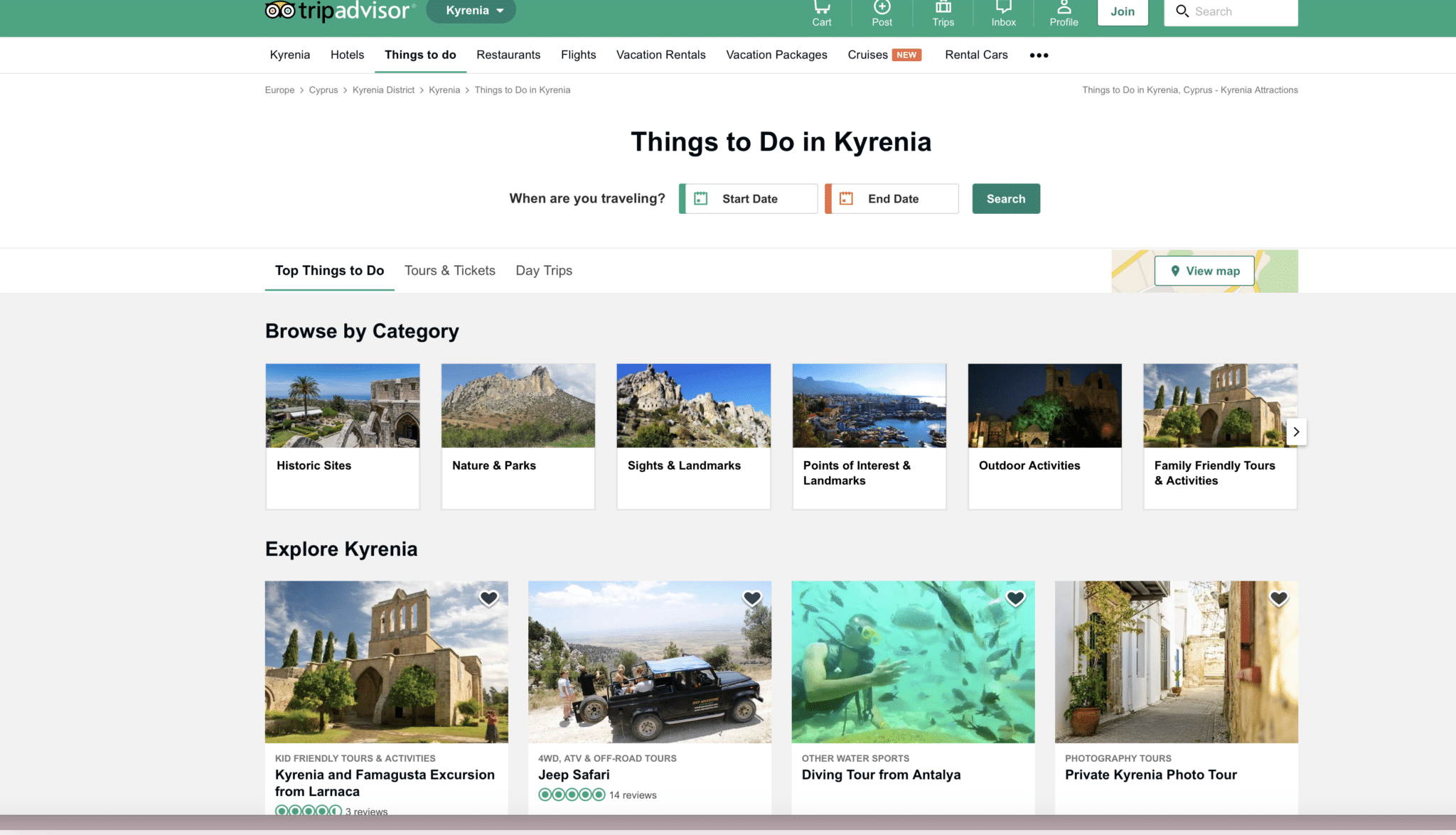

Turkey in Northern Cyprus

Following its 1974 invasion, Turkey maintained an official occupation of Northern Cyprus until 1983, when it helped create a proxy state, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). While the declaration of the TRNC led to sharp criticism against Turkey, the declaration was partly the result of decisions taken by Turkish Cypriots. Both Turkey and the Turkish Cypriots had lost faith in the UN-led negotiations since the 1974 crisis. The Turks were also concerned by the successful efforts of Greek Cypriots to internationalize the dispute by rallying global support for their position as well as condemnation of the Turkish side.

Turkish Cypriots also were concerned that the civilian government expected to take power following the end of military rule in Turkey in 1983 would take a softer position on Cyprus to restore the country’s international standing.69 Under the leadership of Rauf Denktas, Turkish Cypriots established the TRNC.70

Turkey promptly recognized the TRNC, but no other state has followed suit. While Turkey maintains a military presence in Cyprus, it claims the TRNC exercises full sovereignty over the territory. The TRNC does hold regular and competitive elections and maintains a government structure separate from Ankara. It is nevertheless highly dependent on mainland Turkey, not least because of the EU trade embargo against Northern Cyprus, which means that travel and trade with the outside world, including postal links, must go through Turkey.

Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh

Armenia goes to great lengths to create the appearance that Nagorno-Karabakh is an independent state. Even Armenia, however, like the international community, has not recognized it as such.

Senior Armenian officials rotate seamlessly between Yerevan and Nagorno-Karabakh. From 1998 to 2018, Armenia was led by Presidents Robert Kocharyan and Serzh Sarkissian; Kocharyan had previously been the “president” of Nagorno-Karabakh, while Sarkissian had been its “defense minister.” Most of the “ministers” of Nagorno-Karabakh are former Armenian officials. For example, Karen Mirzoyan, who served as “foreign minister” of Nagorno-Karabakh from 2014 to 2017, was an Armenian diplomat for several decades.71 Upon completion of his term in Nagorno-Karabakh, Mirzoyan returned to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Yerevan and served as an advisor to the foreign minister. In June 2019, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan appointed Karen Mirzoyan as Armenia’s ambassador at large.72

Similarly, military commanders rotate between service in Armenia’s formal army and the local Nagorno-Karabakh militia. In 2015, for example, Armenia’s deputy chief of the general staff, Levon Mnatsakanyan, was relieved of his duties and then immediately appointed to serve as the “minister of defense” of Nagorno-Karabakh.73 Following the 2016 “Four-Day War” with Azerbaijan, commemoration of the Armenian dead took place in multiple locations in Armenia74 despite the official Armenian position that the war was between Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh.

Armenian officials openly acknowledge that there is no border regime or customs checkpoint between the Republic of Armenia and the occupied territories.75 On the eve of Armenia’s joining of the Russian-led Eurasian Customs Union, then-Armenian Prime Minister Hovik Abrahamian

stated, “We will remain a single territory, and I believe there can be no other formulations on this issue.”76

There are other indications of Armenia’s singular control. The Nagorno-Karabakh currency is the Armenian dram. Yerevan also assigned Armenian phone and postal codes for Nagorno-Karabakh. International mail to Nagorno-Karabakh is addressed to Armenia. All banks in Nagorno-Karabakh are licensed and supervised by the Central Bank of Armenia (CBA). The CBA reports on activities in Nagorno-Karabakh in its updates to international financial institutions.77 The occupied territories are well-integrated into Armenia’s main infrastructure, including natural gas and electricity. This amounts to de facto annexation. Nevertheless, Armenia has largely escaped international opprobrium for its military control over a sixth of Azerbaijan.

Russia in Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Transnistria, and Donbas

In contrast to its formal annexation of Crimea, Moscow rules through proxy forces in the territories of Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Transnistria, and Donbas. Moscow’s military involvement is well documented, and its claim to be an impartial arbiter and peacekeeper in these conflicts strains credulity.

On occasion, Russian proxies have resisted full Russian control. Abkhazia, in particular, has made efforts to withstand Russian pressure in hopes of achieving independence from both Georgia and Russia. By contrast, South Ossetia and Transnistria have hewed much closer to the Russian line. South Ossetia has even floated the possibility of formal annexation by Russia.78

Following Vladimir Putin’s consolidation of power in the early 2000s, the Kremlin’s control of these territories became tighter. Putin appointed Russian military and security officials to ministerial positions in the governing structures of these territories, indicating their direct subordination to Russia.79 Following its 2008 war with Georgia, Russia established permanent military bases in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and formally recognized the independence of the two territories. This allowed Moscow to create a fictive legal basis for its military presence, based on “inter-state” agreements it signed with its proxies.80

The International Response

The status of territories under Israeli control has remained a focal point of great power diplomacy and UN proceedings for more than 50 years. By contrast, while the division of Kashmir has led to recurrent wars and crises, the international community has tended to view the matter as a dispute to be resolved through mediation by the United Nations. The international community has adopted a similar light touch regarding other protracted conflicts.

Moreover, there have been few serious efforts to challenging the fiction of proxies in certain conflicts. Both the United States and European Union maintain significant sanctions on Moscow and refuse to recognize its claims. Russia also faced sanctions in the summer of 2008 after its assault on Georgia, yet they were lifted during the international financial crisis that autumn. Only four states besides Russia – Venezuela, Nicaragua, Nauru, and Syria – recognized the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Nor has Russia secured recognition for its proxy in Transnistria. Nonetheless, there is tacit acceptance of Russian control in these cases, partly because of limited concern for the affected populations, and partly due to the difficulty of changing Russian behavior.

Armenia has encountered mainly symbolic opposition to its occupation of Nagorno-Karabakh, with no concrete sanctions or enforcement actions. UN Security Council resolutions have condemned “displacement of large numbers of civilians in the Azerbaijani Republic” and the occupation of Azerbaijani territory. But they have refrained from directly identifying an aggressor, in part due to the insistence of Russia, which protects Armenia’s interests at the United Nations.

The case of Northern Cyprus is an outlier. The initial Turkish invasion of Cyprus triggered an immediate and overwhelming international condemnation. The U.S. Congress imposed an arms embargo on Turkey that lasted almost four years. Northern Cyprus later came under a near-total international trade embargo. Initially, EU states accepted goods stamped by Turkish authorities in Northern Cyprus, but the internationally recognized government in Nicosia obtained an ECJ ruling in 1994 that banned direct imports from the TRNC.81 Given that 74 percent of TRNC exports went to the European Union, this was a considerable hit to the TRNC economy.82 Following the failure of a 2004 peace plan, the European Union accepted Cyprus as a member state. Today, Turkish Cypriots technically reside in the European Union but are unable to trade with other members.

EU legal institutions continue to put pressure on Turkey and the TRNC. In the landmark case of Loizidou v. Turkey in 1996, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled that Turkey “exercised effective control” over the TRNC owing to Turkey’s large military presence on the island.83 This was confirmed several years later in an inter-state case, Cyprus v. Turkey, in which the ECHR sentenced Turkey to pay the Republic of Cyprus €90 million in damages, which Turkey has refused to pay.84 These cases have implications for other territorial disputes, which have resulted in similar litigation that led to judgements against other occupying powers. Whether such judgements will influence those powers’ behavior is difficult to predict.

Still, the precedent set in Loizidiou carried obvious implications for other conflicts. In 2004, the ECHR ruled on a case filed by individuals imprisoned by Transnistrian authorities, concluding that Russia’s backing of secessionist authorities in Transnistria amounted to effective control.85 This legal precedent was confirmed by a 2015 ruling in Chiragov and Others v. Armenia. Armenia argued that its role in Nagorno-Karabakh was fundamentally different from Turkey’s in Cyprus or Russia’s in Moldova. But the court concluded that “Armenia, from the early days of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, has had a significant and decisive influence over the ‘NKR’, that the two entities are highly integrated in virtually all important matters and that this situation persists to this day.”86 At the time of this writing, cases on Russia’s role in Abkhazia were pending before the ECHR.

In summary, occupying powers have assumed varying levels of accountability for the territories they rule and the people living there. Curiously, the states that fully acknowledge their presence and take responsibility for the security of the territories and their residents – Israel in the West Bank and Russia in Crimea – have received the harshest condemnations, sanctions, and other penalties. By contrast, those that establish ostensibly independent proxy regimes can occupy other territories with little consequence. Russia, for instance, occupies five foreign regions: Crimea, Donbas, Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Transnistria. Yet Moscow is subject to punitive measures primarily for the one occupation it admits – Crimea, whereas it has had more success in making use of its “deniability” in Eastern Ukraine. Thus, proxies appear to afford the international community the convenient or politically expedient option of ignoring select occupations.

Settlement Projects and Demographic Changes

Demographic change is a common consequence of conflict. In some cases, the local population flees or is driven out.87 To exercise effective control, occupying powers often resettle their own citizens there, frequently encouraging this relocation by means of economic incentives.

This combination of flight, expulsion, and settlement often leads to enduring grievances. Yet international concern has rarely been proportional or consistent. Armenia expelled over 700,000 Azerbaijanis from Nagorno-Karabakh and adjacent regions, then implemented a settlement program. Yet Yerevan has faced no consequences. Turkey enacted a similar policy in Northern Cyprus, and Morocco imported hundreds of thousands of settlers into Western Sahara to tip the demographic balance. However, the preponderance of diplomatic initiatives and media coverage have focused on Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Gaza, where the local population has mostly remained. This offers aggressors a problematic lesson: expulsion works.

Residing PopulationsNot expelled:

Partial flight of populations during military conflict and pressure on population to emigrate from the regions:

Intentional policy of expulsion of residing population

|

This chapter analyzes the use of settlements to change demographic balances, affect referendum outcomes, create economic opportunities for the occupying state and its citizens, and construct infrastructure to create barriers to changing a given territory’s status.

Case Studies

Israel and the Palestinians

While Israel gained substantial territory in the process of repelling the Arab invasion of 1948, it lost territories to Jordan that had been allocated to the Jewish state as part of the proposed UN Partition Agreement.88 Centuries-old communities in Jerusalem and the West Bank took flight or faced expulsion. Thus, following Israel’s capture of the West Bank and East Jerusalem in 1967, many Israelis desired to return to lost places of residence. The first community built following the 1967 war was Kfar Etzion, a village captured by Jordan during the 1948 war.89

Initially, Israel’s policy regarding settlements in the West Bank was to establish them only in areas of strategic importance, such as the Jordan Valley, or in areas of exceptional religious and national significance, such as Hebron. At the same time, Israel hoped to return to the Arab countries or even to the Palestinians control of the lands that were densely populated or non-essential in terms of security.90 However, the Arab League’s rejectionism rendered this goal moot.

Following the ascension of the right-wing Likud Party in 1977, Israel began to allow the construction of additional settlements in the territories, even if they served no security need. However, there is an important distinction in the Israeli settlement projects from other cases examined in this study. The Israeli government and Supreme Court allowed settlements to be built only on state lands – in other words, land that was previously held by the government of Jordan – or acquired legally from private individuals. Furthermore, settlements required government approval and had to comply with planning and zoning regulations. Those failing to meet these requirements were subject to evacuation.91

Israel has designated numerous settlements as National Priority Areas to encourage migration, construction, and economic growth.92 These areas receive government funds for new housing, and individuals can receive subsidized loans.93 Certain individuals in National Priority Areas also receive tax benefits, based on geographic and economic criteria.94

Private individuals and NGOs have since built dozens of unauthorized settlements in the West Bank. In many cases, the Israeli government looked the other way. But in 2018, the prime minister’s office published the results of a study designed to address this problem.95

According to official Israeli data, as of 2017, there were 126 settlements and 414,400 Jewish Israeli citizens living in the West Bank.96 According to the Palestinian census in 2017, 2.8 million Palestinians resided in the West Bank.97 There are no Israeli settlements in the Gaza Strip; all were evacuated in 2005 as part of Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s unilateral disengagement plan.98 As part of this plan, the Israeli government forcibly removed over 9,000 Israelis living in 25 settlements.99

The overwhelming majority of Israeli settlers live in the large settlement blocs of the West Bank, such as Ma’ale Adumim and Ariel, located adjacent to Israel’s 1967 borders. The concentration of settlers in locations adjacent to Israel means that almost all of the West Bank could potentially still be relinquished to the Palestinians as part of a future peace agreement, while these settlements could be integrated into Israel as the result of a land swap.

Some financial support for the settlements comes from abroad, not just from the Israeli government. According to a 2010 report by The New York Times, at least 40 U.S.-based groups collected more than $200 million in tax-deductible gifts for Jewish settlements over that past decade.100 In Canada, on the other hand, the government revoked the charity status of an organization that contributed to Israeli settlements. Ottawa claimed the organization served to encourage and enhance the permanence of the settlements, thereby contravening Canadian policy.101

Northern Cyprus

Before the unrest of the 1960s, there was no clear division between Turkish and Greek areas in Cyprus. But inter-ethnic violence erupted in the 1960s as a Greek Cypriot campaign for unification with Greece intensified. As a result of its invasion in 1974, Ankara asserted control over 40 percent of the island’s territory, leading to the expulsion of some 150,000 Greeks. The 50,000 Turks who lived in the island’s south fled to the Turkish-controlled north.102

Subsequent policies reinforced demographic changes. The TRNC and Turkey encouraged emigration from Turkey to Northern Cyprus, including through a formal program from 1974 to 1979 designed to settle new citizens from Turkey. Turkish immigrants received citizenship in the TRNC and lived in houses that had been the property of Greek Cypriots. The TRNC set up a Ministry of Resettlement103 and sponsored programs to assist the absorption of Turkish settlers. The properties of former Greek residents of the North were redistributed.104 Farmland and livestock were distributed to the new immigrants, and food was supplied until Turkish settlers could provide for themselves. Estimates of the number of Turkish settlers in the TRNC during this period range between 15,000 and 30,000.105 These policies ended in 1980.106

Later waves of immigration to the TRNC from Turkey took place without formal facilitation by the local or Turkish authorities.107 However, the TRNC has lax immigration laws that enable application for citizenship after a year of residence and grants citizenship to members of the Turkish military who served on the island and to families of Turkish soldiers who died in the 1974 war. The children and grandchildren of the settlers from both periods of Turkish emigration to the TRNC received citizenship as well.108

Thus, since 1980, approximately 30,000 additional settlers from Turkey have received citizenship in the TRNC. Today, settlers from Turkey and their descendants outnumber native Turkish Cypriots. In addition, an estimated 70,000 Turkish citizens reside in the TRNC but have not received local citizenship.109 They include university students and migrant workers.

Western Sahara

The Western Sahara conflict (1975-1991) led to the flight of nearly half of the indigenous Sahrawi population. Many found shelter in Polisario-run refugee camps in southwestern Algeria. However, a Sahrawi population of about 150,000 remained in Western Sahara under Moroccan rule.

Through an extensive settlement project, the Moroccan government has succeeded in changing the demographic balance in Western Sahara. Settlers from Morocco now outnumber the indigenous Sahrawis. Assessments place the number of Moroccan settlers at between 200,000 and 300,000, constituting over half of the total population. According to the CIA’s World Factbook, “Morocco maintains a large military presence in Western Sahara and has encouraged its citizens to settle there, offering bonuses, pay raises, and food subsidies to civil servants and a tax exemption.”110

Rabat dedicates significant public investment to Western Sahara, some generated from a special tax devoted to investments in the territory. Accordingly, economic and human development indicators are higher in Western Sahara than in Morocco proper, an indication that the government invests significantly in this region. All of these measures help ensure that any future referendum on the region would not result in support for independence.

The Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict

During their capture of Nagorno-Karabakh and seven surrounding districts of Azerbaijan in 1992-94, Armenian forces evicted all the Azerbaijani residents of the region, who numbered over 700,000. Officials in Armenia, local authorities in Nagorno-Karabakh, and diaspora organizations have since touted their efforts to bring settlers to the occupied territories.111 A local official stated that settlers are recruited from both Armenia and foreign countries.112 Independent observers, such as fact-finding missions from the OSCE, have documented evidence of the Armenian settlements.113 According to the OSCE, 3,000 Armenian settlers live in the town of Lachin, mostly in former homes of Azerbaijanis who fled during the war. New settlers, according to the report, received “incentives offered by the local authorities[,] include[ing] free housing, access to property, social infrastructure, inexpensive or sometimes free electricity, running water, [and] low taxes or limited tax exemptions.”114 A report published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Azerbaijan, using satellite images, also documents the settlements and their expansions.115

There are three categories of Armenian-occupied territories of Azerbaijan: Nagorno-Karabakh proper; the regions of Lachin and Kelbajar that lie between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh; and five additional adjacent administrative regions of Azerbaijan. The Armenian settlement project has mainly focused on Nagorno-Karabakh and the Lachin and Kelbajar regions. Lachin has strategic value because it forms a narrow corridor separating Nagorno-Karabakh from Armenia. Through settlements, Armenia aims to retain control of Lachin in the event there is a future peace settlement.

Armenian settlers are housed both in homes that belonged to Azerbaijani residents and new settlements built by Armenian authorities. Settlers lease land for free, receive loans for livestock and small business, and enjoy free utilities.116 Settlements receive funding from a variety of sources, including direct Armenian government funding,117 funds from Armenian diaspora communities, and even limited USAID funds.118

The “prime minister” of Nagorno-Karabakh, Ara Harutyunyan, described the goals for the settlements as the establishment of political control of the region and deriving economic benefit from the occupied lands: “We are the owners of these lands and by the appropriation of them we answer the political question. Second, that we are using these lands for food provision and, in general, economic purposes.”119

The U.S. Congress has actually appropriated foreign aid for Nagorno-Karabakh since 1998. Some of these funds have been used to construct homes in the occupied territories. U.S. aid allocations totaled over $40 million between 1998 and 2012.120 According to Armenian reports, U.S. appropriations have been used for “construction of homes in sixty villages, water supply projects in forty villages and renovation of twelve schools in different provinces of Nagorno-Karabakh.”121

In addition, the settlements benefit from the support of several Armenian-American diaspora organizations that operate in the United States as tax-free non-profits. One vehicle for settlement funding is the Artsakh Fund,122 run by the Armenian Cultural Association of America.123 The project focuses on new housing and public buildings in occupied Gubadli region and openly calls the activities “resettlement projects.”124

The Los Angeles-based Hayastan All-Armenian Fund also supports settlement activity in the occupied territories, focusing on major infrastructure projects. The fund sponsored two highways between Armenia and the occupied territories.125 The fund also sponsors water, power, and other infrastructure projects and raises money through annual telethons in the United States. The New Jersey-based Tufenkian Foundation similarly boasts that it has “built a new [settlement] from the ground up – the Arajamugh village.”126

Since 2012, a new wave of settlers has arrived in Nagorno-Karabakh127 as a result of the Syrian civil war. Ethnic Armenians from Syria are encouraged to settle in the occupied territories, and receive free housing, free utilities, free agricultural equipment, tax breaks, and financial support as incentives.128 Armenia has actually received funds from the European Union to settle these Syrians in Armenia.129 There is no evidence that Brussels has tried to prevent use of the funds for settlement in Nagorno-Karabakh and the additional occupied districts.

Resistance to Settlement in Jammu and Kashmir and Abkhazia

The local powers in both Jammu and Kashmir and Abkhazia have resisted settlement activity. In Abkhazia, Moscow has made efforts to settle Russians, but the Abkhaz local authorities have resisted pressure to pass legislation that would allow foreign citizens (read: Russians) to own property.130 Russian citizens own and operate extensive business and infrastructure projects in Abkhazia, but most do not take up permanent residence there.

As for Kashmir, India’s constitution explicitly guarantees the local IJK legislature the right to determine who is a permanent resident, which in turn determines the applicability of property rights. As a result, there was no significant migration of people from India into Jammu and Kashmir, and populations that moved there in the 1950s never gained permanent residency.131 The Modi government’s 2019 abrogation of IJK’s special status largely was designed to ensure that Indians from outside IJK could move there. It remains to be seen whether the changes in IJK’s legal status, if upheld by Indian courts, will lead to significant migration – something that may be deterred by recent violence in the area.

***

Settlement activity in occupied territories is quite common and is often the result of extensive programs sponsored by the occupying power. In some cases, such as with Israel and Armenia, diaspora organizations are active in promoting the settlement activity. In the case of Armenia, even congressionally appropriated funds have openly been used to construct settlement homes in the occupied territories, without consequence or condemnation within the U.S. Congress or from NGOs.

Once again, the international response reveals imbalance and bias. Despite the extensive settlement activity in most zones of protracted conflicts, the only settlement project that attracts the attention of international human rights organizations, governments, and the United Nations is that conducted by Israel.

U.S., EU, UN, and Corporate Trade Regulations

Protracted territorial disputes have politicized bureaucratic functions such as customs regulations that otherwise might have remained purely technical matters. These functions often help determine whether an occupied territory will be treated as part of the occupying country or as a distinct entity. If the occupier has concluded free trade agreements with the United States or European Union, will such privileges extend to the occupied territory? Will the United States or European Union require labels indicating that imports originated in an occupied territory? Will the customs status of a territory create a loophole in economic sanctions that target the occupying power?

The private sector also has to contend with such questions. Decisions of whether to operate in certain territories become political and legal matters. Even if such conduct is entirely legal, activists may pressure corporations to divest – and a decision to do so would likely prompt criticism from the opposing side.

Governments and corporations have an interest in formulating clear and consistent policies. Doing so can blunt accusations that they apply double standards. For businesses, equitable treatment is especially important to counter claims of discriminatory practices. However, such decisions tend to be made on an ad hoc basis that reflects the pressures of the moment.

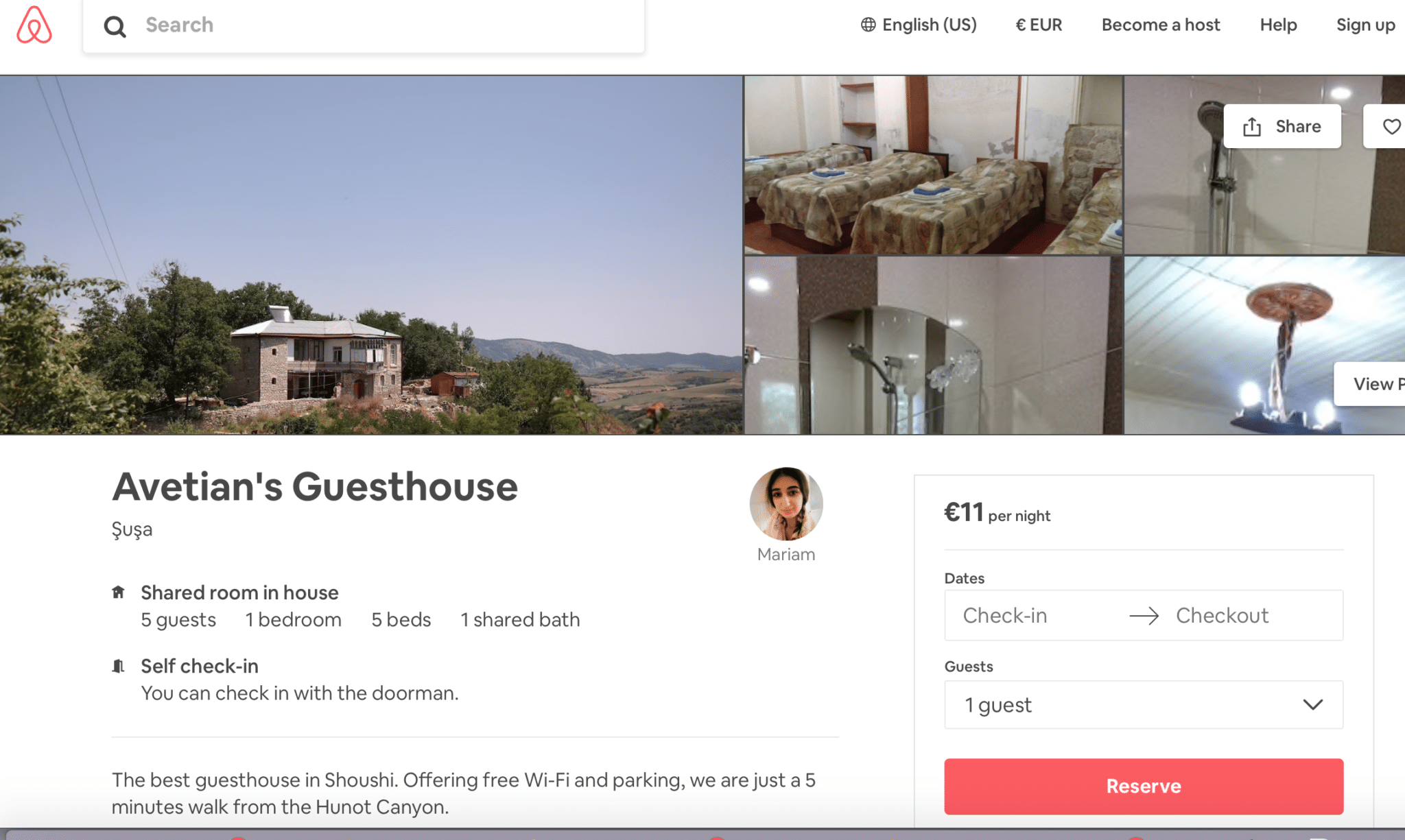

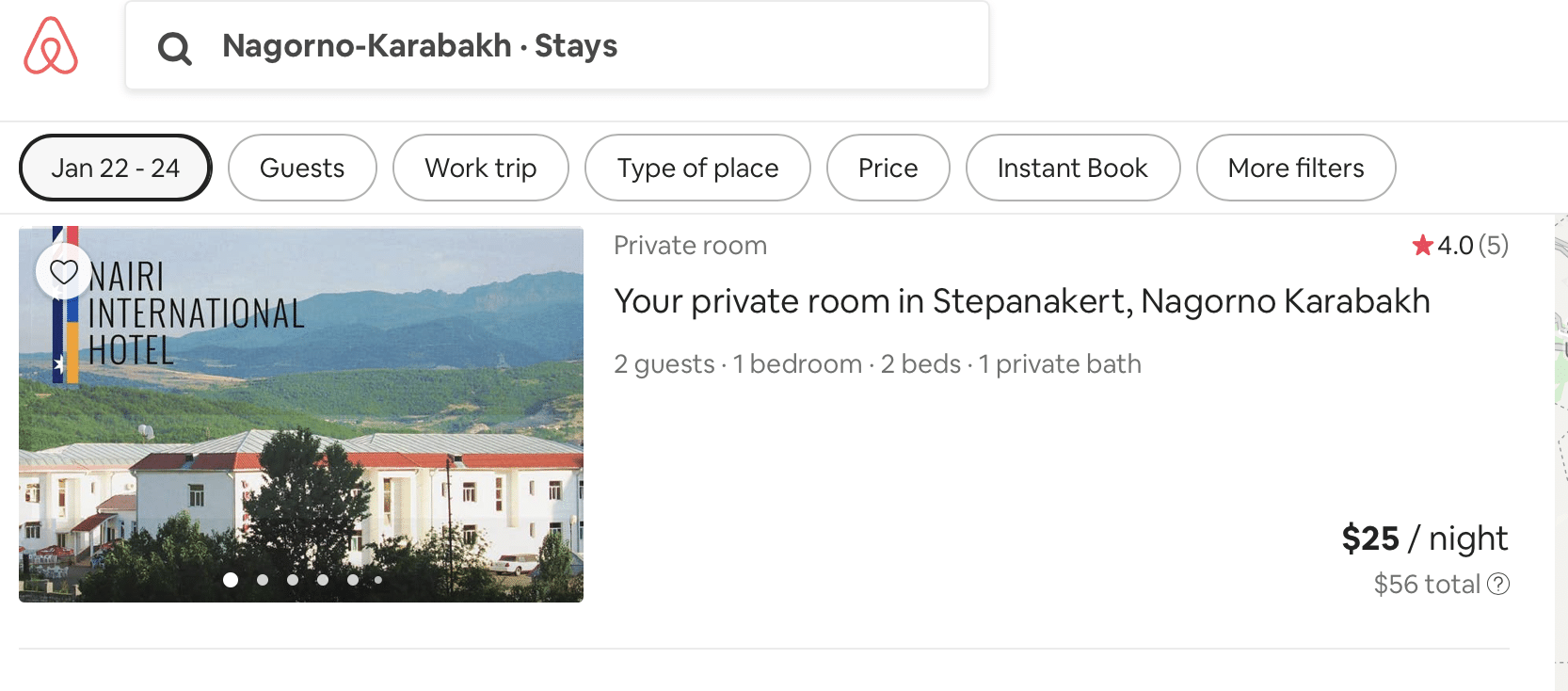

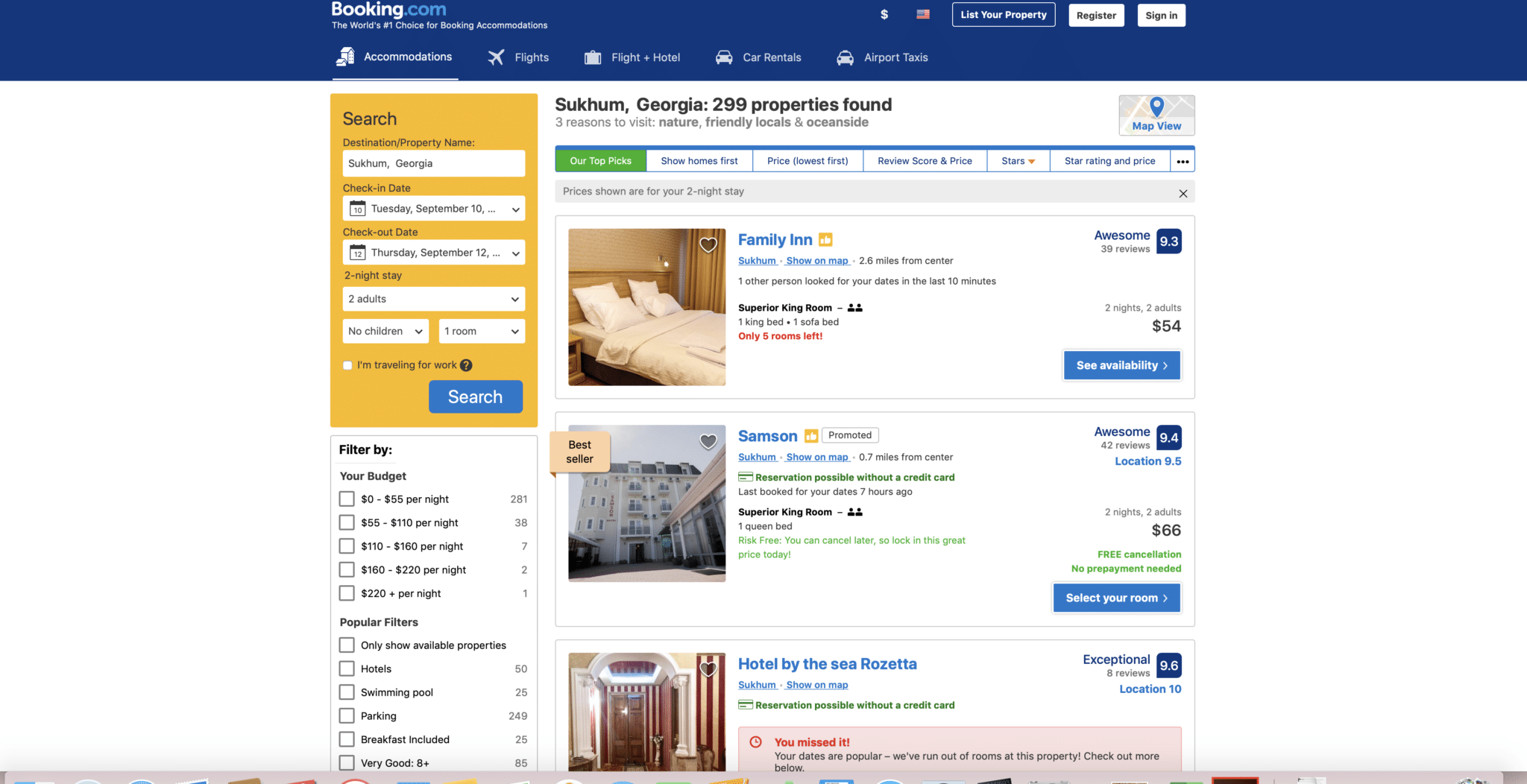

Israel has often been the sole target of divestment advocacy campaigns. Under pressure from activists, the United States and European Union prohibit the use of “Made in Israel” labels for West Bank goods yet have not applied similar rules to Western Sahara, Transnistria, and others. The UN Human Rights Council similarly compiles a database of companies that operate in the West Bank and has issued letters warning those companies that they risk being declared human rights violators. Yet there are no parallel efforts for other similar territories. Meanwhile, NGOs including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have pressured tourism service companies, such as Airbnb, Booking.com, and Expedia, to exclude Israeli-controlled territories. Once again, these NGOs have not addressed other protracted conflicts.

U.S. Policies

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) monitors all goods imported to the United States and requires accuracy in statements of origin. To date, CBP has issued explicit directives pertaining to the territories under Israel’s control, but has done so for only one of the four regions under Russian control (Crimea). In other cases, CBP effectively allows goods to be imported with no indication they were produced in areas of occupation, in violation of CBP regulations. Indeed, there are multiple cases wherein goods produced in occupied territories entered the U.S. market with erroneous country-of-origin labels yet the importers faced no consequences. Some exporters make no secret of the mechanisms they employ to circumvent CBP regulations, such as registering companies outside the occupied zone. In fact, these exporters even openly promote this technique as a marketing tool.132

Israel and the Palestinians

In the case of Israel, CBP has clarified that goods produced in the West Bank cannot be registered as produced by companies based in Israel proper and then imported with the label “Product of Israel.” Instead, U.S. customs regulations require goods produced in the West Bank and/or Gaza to be clearly demarcated.133 The labels cannot contain the words “Israel,” “Made in Israel,” “Occupied Territories-Israel,” or words of similar meaning.134 This policy originated shortly after the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993.135 U.S. policy does not differentiate between goods produced in Israeli settlements versus those made by Palestinians residing in the territories.

In 2016, CBP issued public guidance reaffirming its policy, warning, “Goods that are erroneously marked as products of Israel will be subject to an enforcement action carried out by U.S. Customs and Border Protection.”136 CBP has also made clear that the West Bank origin of goods cannot be circumvented by registering a company within Israel’s pre-1967 borders.

At a 2016 State Department briefing, a journalist asked whether this policy applied to comparable territories. The State Department spokesman rejected this.137

Western Sahara, Cyprus and Jammu and Kashmir

The CBP has not published guidelines related to the labeling of goods from Western Sahara or Turkish Cyprus. The U.S. trade agreement with Morocco covers all goods from Morocco, with no differentiation of goods produced in the occupied region.138 Nor are there any guidelines related to imports from either Pakistani-administered or Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir. Products from these territories are simply labeled as made in either Pakistan or India.

Armenia

Despite the U.S. recognition of Nagorno-Karabakh and the surrounding regions as the legal territory of Azerbaijan, the CBP has not clarified that goods from these territories should be marked as such. Producers in the occupied territory openly admit they mark their goods “Product of Armenia” when exporting to the U.S. As a recent news story about one producer revealed, “The company exports to the United States, Canada, Russia, and the EU, all via a corporate registration in Armenia, a tool Karabakh producers use; Ohanyan’s brandies and Avetissyan’s wines show up in Los Angeles and Chicago with ‘Product of Armenia’ on their labels.”139 The label “Product of Armenia” even appears on products openly advertised as being from the occupied territories.140

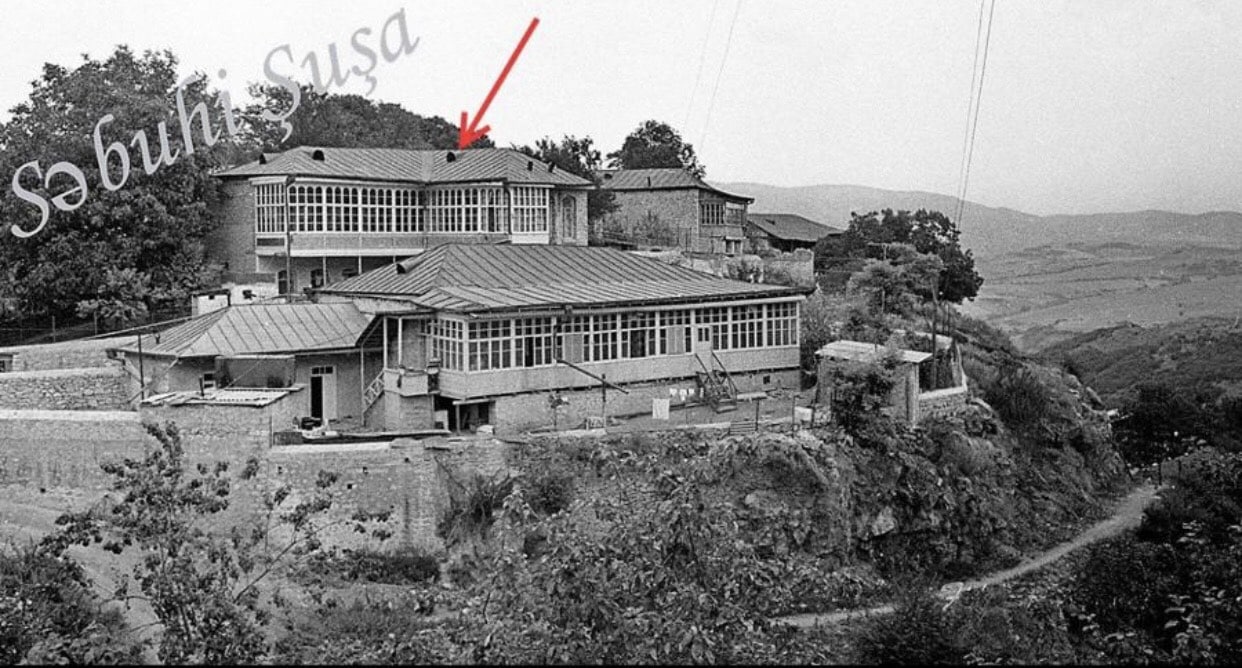

Above: The Kataro Winery is located in occupied Nagorno-Karabakh,141 but its wines are labeled “Product of Armenia,” in violation of CBP certificate-of-origin requirements.

Above: This grilled vegetable mix produced by Artsakh Berry, a company based in the occupied territories of Azerbaijan,142 enters the United States as a “Product of Armenia.” The company is registered with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration through a company located in Armenia.143

Russia’s Occupied Regions