June 14, 2021 | Monograph

Skinheads, Saints, and (National) Socialists

An Overview of the Transnational White Supremacist Extremist Movement

June 14, 2021 | Monograph

Skinheads, Saints, and (National) Socialists

An Overview of the Transnational White Supremacist Extremist Movement

Introduction

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s October 2020 Homeland Threat Assessment states that among domestic violent extremists, “racially and ethnically motivated violent extremists—specifically white supremacist extremists (WSEs)—will remain the most persistent and lethal threat in the Homeland.”1 The threat has been made clear through multiple lethal acts perpetrated by WSEs. The deadliest and most prominent recent attack was an August 2019 mass shooting at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, that claimed 22 lives. It was the third-deadliest domestic extremist attack in 50 years.2 Beyond lone acts of terrorism, organized networks such as Atomwaffen Division (AWD) and The Base – both of which have been significantly disrupted, as this report details – have plotted terrorist attacks in recent years to advance their goal of overthrowing the U.S. government and triggering a race war.

The January 6, 2021, insurrection on Capitol Hill cast a spotlight on the WSE movement, as some people associated with WSE groups took part and displayed white power symbols, including a now-infamous “Camp Auschwitz” sweatshirt.3 Though the events of January 6 should not be over-interpreted as driven by WSEs – multiple types of rioters, grievances, and belief systems were involved – the insurrection underscored how WSEs can exploit our fractured political environment. In 2020–2021, the United States lurched discernibly toward armed politics and violent activism; multiple factions and movements resorted to the use or threat of violence to pursue their objectives. The country witnessed scenes not glimpsed in decades, such as armed citizens patrolling the streets in Georgia, Kentucky, Minnesota, and Wisconsin.4 The involvement of WSEs in the Capitol Hill attack and other events during this tumultuous period points to their ability to exploit societal fractures and the general rise in extremism.

At the same time, WSE activity has taken on an increasingly transnational dimension. WSEs are developing cross-border connections with like-minded individuals and groups, sharing ideologies and practical knowledge with their foreign counterparts, both in person and online. The growing transnationalism of the movement has inspired further attacks across the globe and fueled extremist recruitment.

This report is designed to provide an overview of white supremacist extremism, both domestic and international. It addresses key WSE ideologies, major domestic and foreign WSE groups, the nature of the WSE threat in the United States, and transnational WSE activity. The report is not comprehensive: The universe of WSE actors is large, regionally varied, and constantly in flux as political conditions and the actions of law enforcement shape its development. Nonetheless, this report should provide a solid foundation for understanding the threat today and an indication of how the WSE movement may continue to evolve.

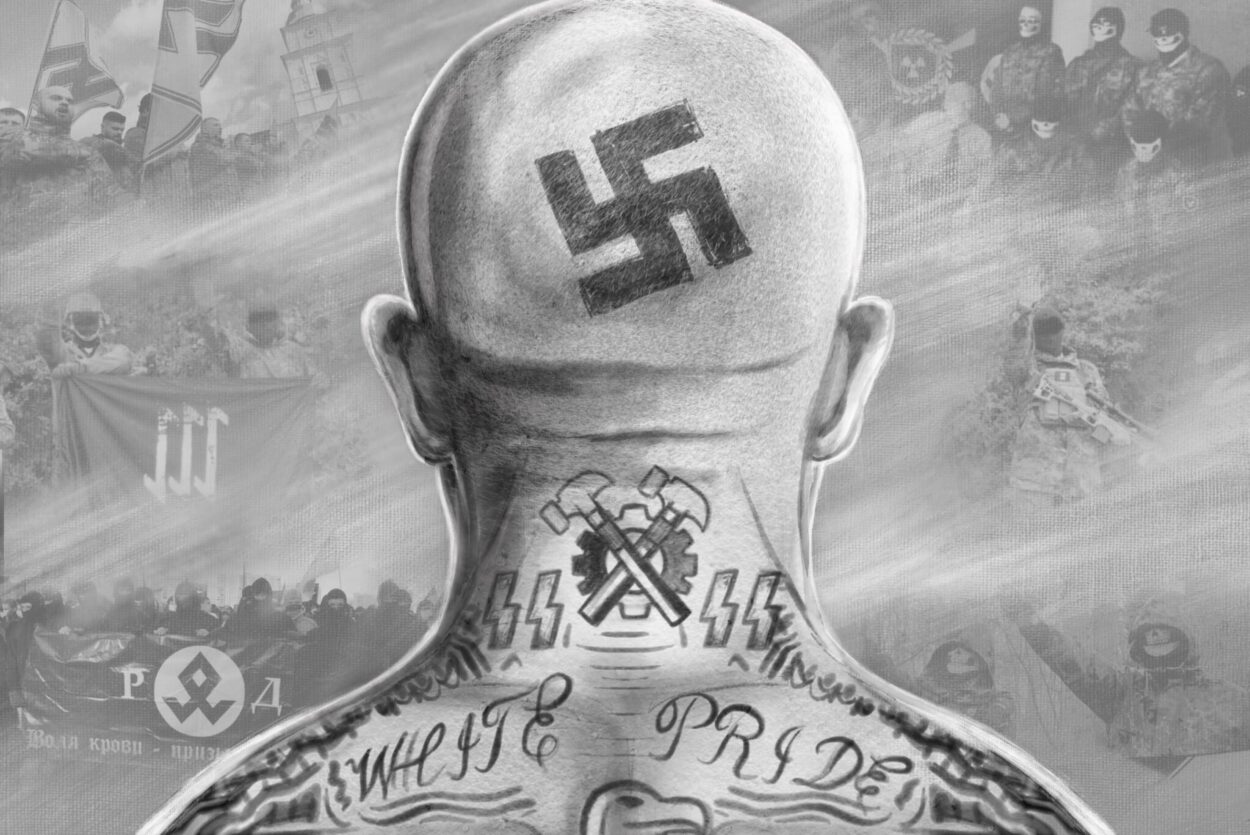

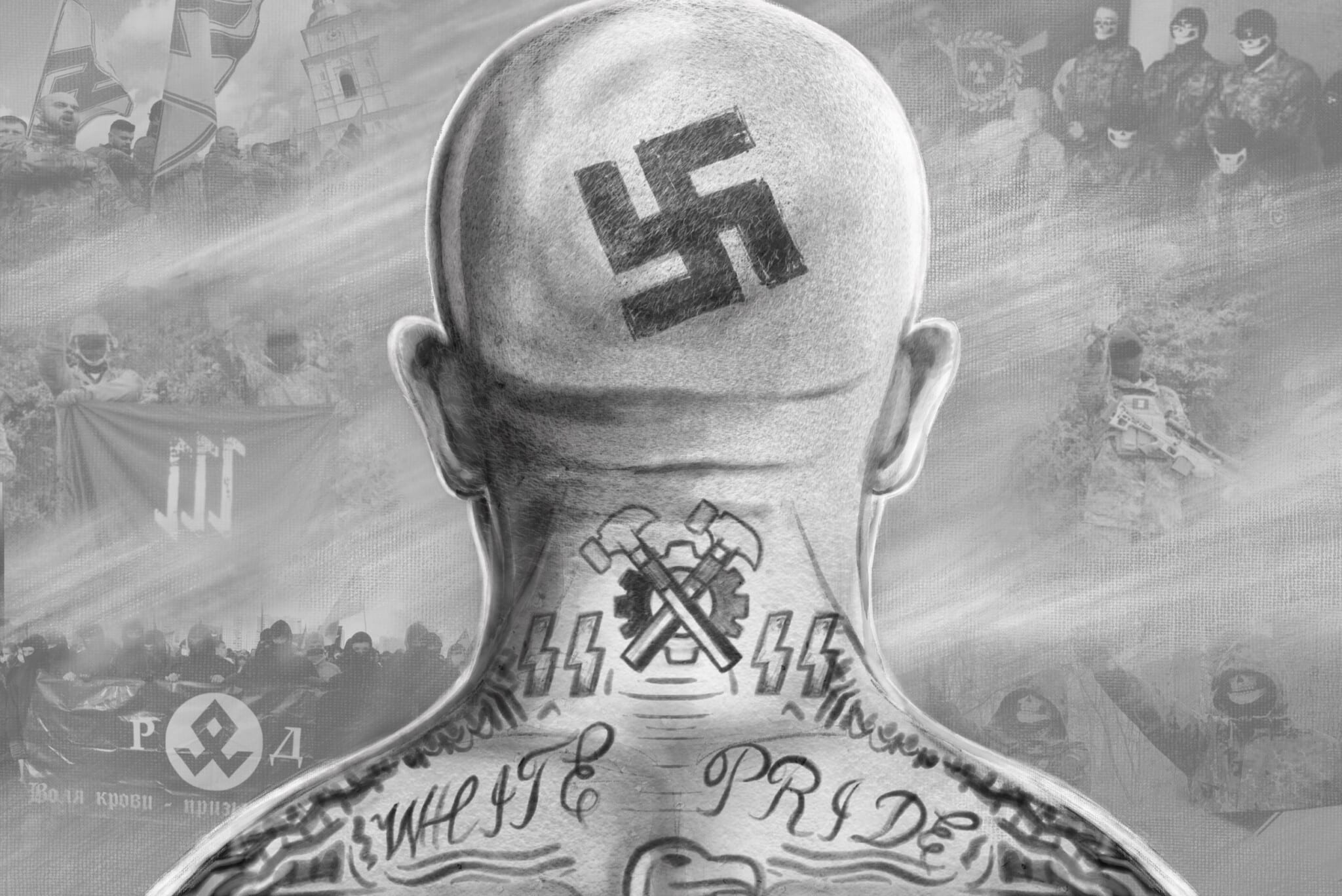

Illustration by Daniel Ackerman/FDD. Editorial images in cover background (clockwise from top left): Veterans of the Azov volunteer battalion salute during a rally in Kyiv, Ukraine, on March 14, 2020. (Photo by Sergei Supinsky/AFP via Getty Images); Members of the Atomwaffen Division. (Photo by AWD via 12 News); Members of “The Base” pose for photos that were used as propaganda. (Propaganda image via BBC News); Member of Feuerkrieg Division in a picture posted in an online chat. (Eugene Antifa via The Independent); Russian ultranationalists hold a march in Moscow, Russia, on November 4, 2009. (Photo by Alaexey Sazonov/AFP via Getty Images); Members of “The Base” pose for photos that were used as propaganda. (Propaganda image via BBC News).

Illustration by Daniel Ackerman/FDD. Editorial images in cover background (clockwise from top left): Veterans of the Azov volunteer battalion salute during a rally in Kyiv, Ukraine, on March 14, 2020. (Photo by Sergei Supinsky/AFP via Getty Images); Members of the Atomwaffen Division. (Photo by AWD via 12 News); Members of “The Base” pose for photos that were used as propaganda. (Propaganda image via BBC News); Member of Feuerkrieg Division in a picture posted in an online chat. (Eugene Antifa via The Independent); Russian ultranationalists hold a march in Moscow, Russia, on November 4, 2009. (Photo by Alaexey Sazonov/AFP via Getty Images); Members of “The Base” pose for photos that were used as propaganda. (Propaganda image via BBC News).

Illustration by Daniel Ackerman/FDD. Editorial images in cover background (clockwise from top left): Veterans of the Azov volunteer battalion salute during a rally in Kyiv, Ukraine, on March 14, 2020. (Photo by Sergei Supinsky/AFP via Getty Images); Members of the Atomwaffen Division. (Photo by AWD via 12 News); Members of “The Base” pose for photos that were used as propaganda. (Propaganda image via BBC News); Member of Feuerkrieg Division in a picture posted in an online chat. (Eugene Antifa via The Independent); Russian ultranationalists hold a march in Moscow, Russia, on November 4, 2009. (Photo by Alaexey Sazonov/AFP via Getty Images); Members of “The Base” pose for photos that were used as propaganda. (Propaganda image via BBC News).

Ideologies: Global Trends

Global WSE movements are bound by shared ideologies. Generally speaking, they are driven by a belief in the necessity of white power and the superiority of the white race as well as by fears of cultural and ethnic extinction, irrelevance, or subjugation. Divisions in the movement commonly stem from differences in goals and ideology and from disagreements regarding the use of violence. Many WSE leaders explicitly call for violence against the movement’s enemies, arguing for its necessity and characterizing like-minded but nonviolent groups as weak and unable to create social change. Other WSE leaders and groups view public association with violence as a threat to their ability to operate, fearing that it will attract the interest of law enforcement, interfere with their ability to recruit and retain members, and hamper fundraising. Some leaders and groups officially disavow violence but tolerate, tacitly accept, or are unable to control its use by group members.

Anders Breivik (left) and Dylann Roof (center) were cited in the manifesto of Brenton Tarrant (right).

Brenton Tarrant was subsequently cited in the manifestos of both John T. Earnest (center) and Patrick Crusius (right).

The transnational character of WSE ideologies is evident in the manifestos and social media posts of WSE terrorists who carried out prominent recent attacks. Brenton Tarrant attacked two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, in a mass shooting on March 15, 2019, killing 51. Before the shooting, he posted a manifesto on the web forum 8chan, in which he cited multiple WSE mass killers as his inspiration, including Anders Breivik, the perpetrator of the 2011 attacks in Norway that killed 77, and Dylann Roof, who killed nine in a 2015 shooting at a black church in South Carolina.5 John T. Earnest also published a letter on 8chan before launching an April 2019 attack on the Chabad of Poway synagogue in Poway, California, which killed one and injured three. In the letter, Earnest claimed inspiration from Tarrant’s actions and manifesto.6 Patrick Crusius published his own manifesto on 8chan with a similar reference to Tarrant before carrying out the aforementioned August 2019 shooting at an El Paso Walmart. Crusius wrote: “I support the Christchurch shooter and his manifesto. This attack is a response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas.”7 Further, a shooter who attacked a mosque in Bærum, Norway, in August 2019 posted on social media that he was inspired by Tarrant, and also praised Crusius’ attack.8

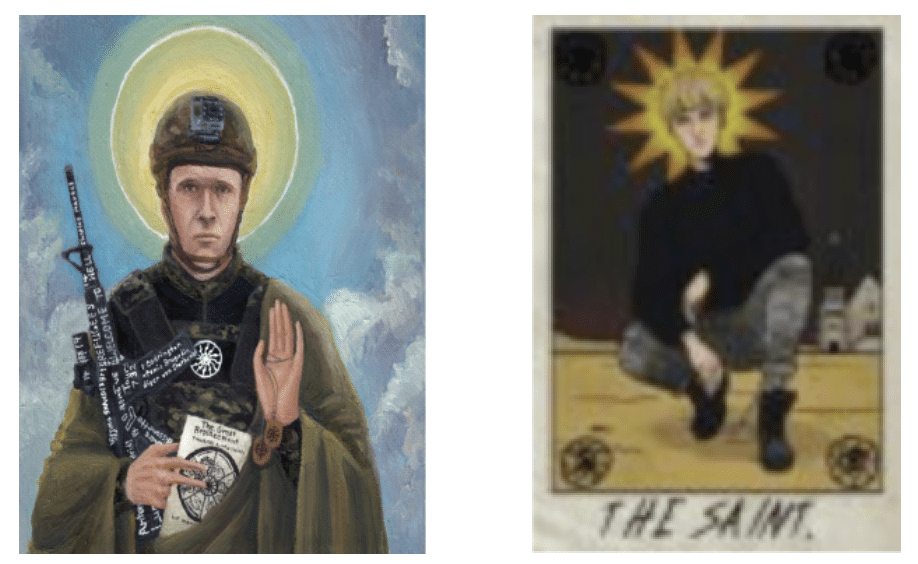

These examples illustrate two central dynamics of the contemporary WSE movement. First, it is transnational. Attackers motivated by WSE beliefs draw inspiration from attacks across the globe. Second, online discourse, particularly on social media, lauds successful attackers as heroes. The most prominent killers are routinely described as “saints” in online forums, with accompanying iconography. As part of the movement’s effort to lionize Tarrant, his manifesto has been translated into several European languages and widely distributed, along with footage from his livestreamed attack.9 A bound edition of a Ukrainian translation has been printed and sold in Eastern Europe.10 The effort to sacralize Tarrant and his attack is designed to convince others to follow.

WSE iconography that depicts Brenton Tarrant (left) and Dylann Roof (right) as saints.

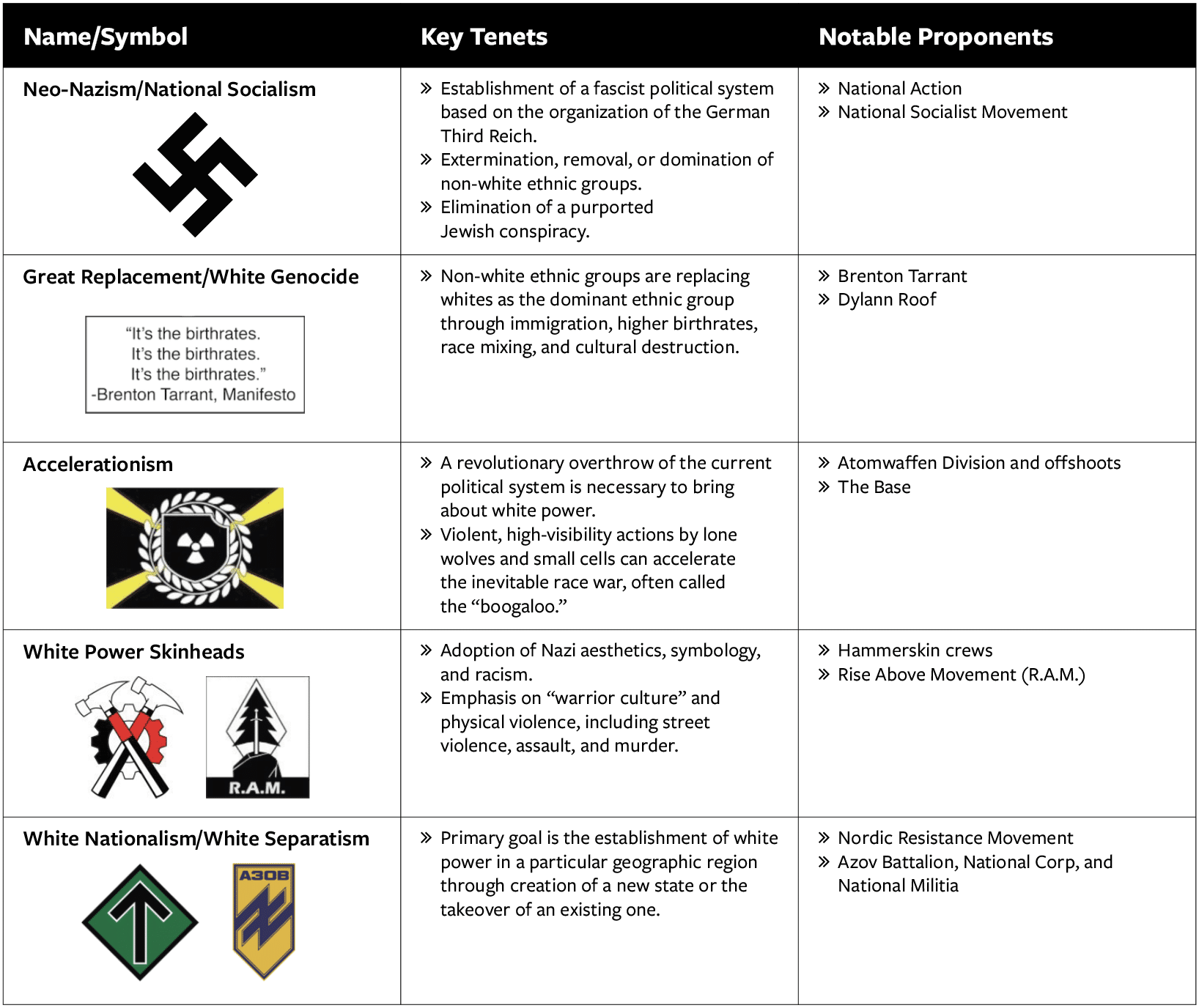

Despite a generally shared canonization of its “saints,” the transnational WSE movement is not an ideological monolith. WSE groups, while existing within the same broad ideological milieu, can differ in various ways, which are summarized in the accompanying graphic.

Major WSE Ideologies

Neo-Nazi and National Socialist Beliefs

Neo-Nazi, national socialist, and fascist ideologies are a core component of the WSE movement. However, not all WSE groups adhere to these beliefs, and many even eschew overt connections with Nazi symbology or ideas. Neo-Nazi and fascist groups espouse core beliefs derived from Third Reich ideology, including emphasizing racial and cultural purity, scapegoating Jews, endorsing exterminationism, and espousing the need for an ethnic homeland.

White Genocide and the Great Replacement

The belief in an ongoing white genocide, or the great replacement of white European-origin populations by non-white immigrants, is widespread among WSEs and the broader white power movement. This theory holds that non-white immigration, multiculturalism, and associated trends pose an existential threat to the white race. Groups adhering to this belief typically point to 1) patterns of mass migration into Western countries, 2) the low birth rates of European-origin families compared to the high birth rates of immigrants from non-European states, and 3) perceived cultural destruction at the hands of immigrants. Renaud Camus’ The Great Replacement, published in 2012, popularized this idea in Europe.11 Other iterations of these beliefs cite antisemitic conspiracy theories to explain the forces driving the purported white genocide. Some WSEs argue that a Jewish conspiracy rules the United States through a shadowy “Zionist occupational government” that seeks to eliminate the white population via immigration, race mixing, and cultural destruction.12

These theories are an important component of many transnational WSE groups and attackers, including the attacks by Breivik, Roof, Tarrant, Earnest, Crusius, and Tree of Life synagogue shooter Robert Bowers.13 Numerous groups that do not employ violence and confine their activities to the political sphere, such as the self-described “Identitarian” movement, also embrace similar ideas. One should not assume that individuals harboring concerns about demographics or white ethnic marginalization have a greater proclivity for violence.

Accelerationism

Accelerationism is the most inherently violent WSE ideology. There are various non-WSE forms of accelerationism, and WSE groups often fuse it with at least one other WSE ideology, such as neo-Nazism. Given the violence associated with accelerationism, it is worth exploring the concept in some detail.

WSE accelerationists believe that a race war is inevitable and the only path to the downfall of the government. They believe that only a violent, revolutionary overthrow of the “System” and victory in the subsequent civil war can achieve the white power movement’s goals. WSE accelerationists typically emphasize the importance of “leaderless resistance,” calling on individuals or small cells to perpetrate revolutionary acts of violence without centralized leadership. The purpose of such attacks is to force the white population to recognize its purported enemy, join a revolutionary uprising, and destroy the System.14 The leaderless resistance strategy is intended to resist law enforcement infiltration.15

The “boogaloo boys” (sometimes “boogaloo bois”) are an overlapping anti-state accelerationist movement that has received national attention but is not inherently white supremacist. While they wish to hasten systemic collapse, they do not necessarily envision a race war or an all-white or white-dominated society.16 The intersecting goals of WSE and non-WSE accelerationists is increasingly concerning.

WSE accelerationists are influenced by a corpus of texts disseminated through internet fora and other channels of communication.17 The ideology is clearest in James Mason’s Siege, which draws on Charles Manson, Adolf Hitler, and American neo-Nazi author William Pierce to promulgate an accelerationist worldview called “Universal Order.”18 Siege was originally a series of newsletters Mason began authoring for the National Socialist Liberation Front in 1980. He continued publishing the newsletters after the Front collapsed in 1982, printing them through 1986. Collected into a single book in 1992, these writings are today considered a defining text of WSE accelerationist groups. Members of AWD and The Base are instructed to read the book.19

William Pierce’s dystopian novel The Turner Diaries is also a guiding text. It depicts a fictional insurgent struggle by a white power terrorist movement against the U.S. government. It advances many of the ideas contained in Siege in a more readily consumable – and, for movement adherents, entertaining – format. WSE accelerationists derive the concept of “the Day of the Rope” from The Turner Diaries. In this ultraviolent fantasy, race-mixing white women, along with white academics, journalists, politicians, and other “race traitors,” are slaughtered en masse. The novel recounts:

Today has been the Day of the Rope—a grim and bloody day, but an unavoidable one. Tonight, from tens of thousands of lampposts, power poles, and trees through this vast metropolitan area the grisly forms hang … each with an identical placard with its legend in large, block letters: “I defiled my race.” … There are many thousands of hanging female corpses like that in this city tonight, all wearing identical placards around their necks. They are the White women who were married or living with Blacks, Jews, or with other non-White males. There are also a number of men wearing the I-defiled-my-race placard, but the women easily outnumber them seven or eight to one.

On the other hand, about ninety per cent of the corpses with the I-betrayed-my-race placards are men, and overall the sexes seem to be roughly balanced. Those wearing the latter placards are the politicians, the lawyers, the businessmen, the TV newscasters, the newspaper reporters and editors, the judges, the teachers, the school officials, the “civic leaders,” the bureaucrats, the preachers, and all the others who, for reasons of career or status or votes or whatever, helped promote or implement the System’s racial program. The System had already paid them their 30 pieces of silver. Today we paid them.20

WSE accelerationism’s call for armed resistance and hastening civil war has produced violent results. The manifestos of both Tarrant and Earnest espouse key concepts of WSE accelerationism.21 Law enforcement has foiled other plots by cells of WSE accelerationists.22 Last year, Der Harte Kern, a small cell in Germany with transnational connections and WSE accelerationist beliefs, planned attacks on 10 mosques in 10 different German states, with the goal of provoking retaliation and triggering civil war.23

White Power Skinheads

White power skinheads are a violent, racist iteration of the British skinhead subculture that emerged in the 1960s.24 The global white power skinhead community holds few consistent political beliefs in common. The movement is heavily influenced by national socialism, though many white power skinheads may embrace the aesthetics, underlying racism, and calls to violence of the historical movement but not its formal political ideology. White power skinhead groups are defined by their embrace of racism and usually emphasize working-class empowerment and “traditional” masculinity (including homophobia). Violence is a key component of white power skinhead subculture; street fighting is a core cultural element of American and European white power skinheads.25

While white power skinhead violence is a persistent criminal threat, it is usually limited to street brawls and targeted assaults. There have been rare instances in which white power skinheads engaged in terrorism and political assassinations. These include Wade Michael Page’s 2012 attack on a Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, which killed six, and Revolution Chemnitz’s plots against German politicians and civil servants, which authorities thwarted in 2018.26

White Nationalism and White Separatism

White nationalist and separatist groups are committed first and foremost to the creation of a white nation in a particular geographic area. Such groups usually draw on a cultural history tied to a particular region or state and emphasize the importance of their perceived home region over the national or transnational political order. The envisioned fate of non-white residents of these homelands varies, with options ranging from the subjugation of non-whites to total exclusion through ethnic cleansing or forced migration. While many white nationalist and separatist groups refrain from using or advocating violence, others employ or encourage violence.

White nationalist and separatist ideologies are not inherently transnational, as their emphasis on a specific geographic area may limit cooperation with foreign WSE groups. For example, ultranationalist Ukrainian WSE groups share significant ideological overlap with ultranationalist Russian WSE groups, but their commitments to the territorial integrity of their respective homelands, coupled in some cases with direct participation on opposite sides of the Ukrainian separatist conflict, leaves little room for cooperation. However, some white nationalist and white separatist groups view themselves as part of a global movement. For example, the League of the South, a neo-Confederate movement in the American South, promotes the secession of former Confederate states but also networks with foreign white power groups. Its leader, Michael Hill, stated, “Whites worldwide must associate in order to help protect our mutual interests against the diabolical forces of globalism that seek our destruction as separate and sovereign nation-states.”27

Major Domestic and Foreign Groups

It is important to note the limitations of applying an organization-focused analytical approach to the WSE movement. Many of the most violent attacks inspired by WSE ideology cannot be traced to specific groups and must instead be understood as phenomena emerging from the broader movement. The perpetrators of the deadliest WSE-linked mass-casualty attacks do not appear to have been members of specific WSE organizations.

Moreover, groups within the movement can drastically change in a short time period. Limited organizational depth leaves most WSE groups highly vulnerable to disruption by law enforcement and fragmentation resulting from internecine disputes. Two of the most violence-oriented groups, AWD and The Base, have declined significantly since their peaks in 2018–2019. AWD’s membership was likely highest around early 2018, with cells across America and members in Canada, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere. Following internal divisions and the arrest of several members, including cell leaders, James Mason announced that the American chapter of the group was disbanding.28 The Base suffered a similar decline following the public revelation of its leader’s identity as a former U.S. government contractor living in Russia as well as the arrest of several of the group’s U.S. members and one Canadian member.29

Though the rise and fall of prominent WSE groups can be rapid and attacks are often perpetrated by “lone wolves,” an exploration of these organizations remains important for understanding major trends in the WSE movement.30 Emergent groups often follow in the footsteps of their predecessors, embracing the same key texts, rhetoric, and techniques as they absorb members abandoning damaged or defunct brands. Former members of collapsing groups often remain active in the WSE movement. Some rebrand their groups with new names and logos, just as former members of AWD did by forming the National Socialist Order following AWD’s “disbandment.” Others form or join new or less prominent groups. One former member of the largely defunct Feuerkrieg Division was arrested on federal weapons charges after joining Iron Youth, an accelerationist group that emerged in 2019.31

Similarly, individual extremists seeking standing in the movement may adopt the iconography of prominent groups or be inspired by their propaganda despite their decline. A participant in the riot at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, was later identified in a video she made that featured symbols and aesthetic elements popularized by AWD.32 A Canadian stopped at the U.S. border in October 2019 was identified as a potential extremist thanks in part to AWD-inspired content on his phone. The man wanted to meet with a U.S. teenager who was seeking to establish a network of neo-Nazi cells.33

Neo-Nazi and National Socialist Groups

National Action was a relatively small (estimated 100 to 200 core activists) UK-based group that openly advocated for national socialism. The United Kingdom added the group to its list of proscribed terrorist organizations in December 2016.34 National Action’s members continued to organize under various aliases after the group was banned, including Scottish Dawn, NS131, and the System Resistance Network. British authorities proscribed all of them.35 The group’s multiple attempts to circumvent the ban suggests ongoing covert activity.

The National Socialist Movement advocates for national socialism in the United States.36 Though the group officially disavows violence, it has previously called for the forceful removal of all non-whites from U.S. territory.37 An individual affiliated with the group attempted to derail an Amtrak train and attack black passengers on board in 2017.38

Logos of WSE accelerationist groups: the Sonnenrad, or Black Sun, of the Sonnenkreig Division (left); the logo of the Feuerkieg Division (top right); and the logo of The Base (bottom right).

Accelerationist Groups

Atomwaffen Division39 is a WSE group with an international membership. The group seems to have emerged in 2015 from the now-defunct internet forum Iron March, though AWD’s founder claims the group was organized several years prior.40 AWD is organized into cells that appear to operate with a high degree of independence.41 The organization has explicitly violent aims and seeks to instigate a race war that will lead to the destruction of the current U.S. political system.42 That said, the specific ideas and ideology of AWD’s members vary somewhat, as its “leaderless” model makes it difficult for AWD to craft a cohesive outlook. However, AWD members have demonstrated a commitment to advancing societal breakdown through violence. Their forums and chat groups circulate a core set of texts, most prominently Mason’s Siege. AWD has inspired related organizations with overlapping membership, including Feuerkrieg Division and Sonnenkrieg Division, which are discussed below.

AWD is active primarily in the United States, where it likely first organized. Since the group’s formation, AWD members have been identified in several states. The group’s social media and propaganda reveal that it has held paramilitary training camps in Texas, Nevada, Illinois, and Washington state.43 The camps feature live-fire weapons training and instruction as well as training in hand-to-hand combat, survival skills, and physical fitness.

Group members have plotted or discussed terrorist attacks. One Florida cell acquired explosives and may have intended to target the electrical grid or a nuclear power plant.44 AWD members also murdered a gay Jewish college student in California and intimidated journalists and political figures.45

In addition to the United States, AWD appears to operate in Germany and Canada.46 U.S. members have reportedly traveled to England, Poland, the Czech Republic, Ukraine, and Germany. While the purpose behind these trips remains unclear, photos of members holding an AWD flag in front of Wewelsburg Castle in the German town of Büren, a site of historical significance for neo-Nazi groups, have appeared in AWD propaganda, including in the announcement of its German branch.47

Sonnenkrieg Division is an AWD-inspired UK-based WSE group that shares AWD’s accelerationist ideology, including its commitment to violence. Members have distributed bomb-making instructions and propaganda encouraging terrorist attacks. Like AWD, Sonnenkrieg’s members have advocated violence.48 Its membership includes former members of National Action, the aforementioned neo-Nazi organization that has been banned in the United Kingdom. In February 2020, the United Kingdom’s home secretary announced that Sonnenkrieg would also be banned as a terrorist group.49 In private forums, Sonnenkrieg members have discussed traveling to the United States to meet with members of AWD.50

Feuerkrieg Division (FKD) is an AWD-inspired group founded in the Baltics, with members in Europe and the United States.51 The group’s propaganda reveals that FKD, like AWD and Sonnenkrieg, embraces violence to provoke a race war.52 FKD has been implicated in terrorist attacks and plots in the United States and Europe.53 The scope of the group’s U.S. presence is not known. Conor Climo, a Las Vegas resident found with bomb-making materials in his home, “was communicating with individuals who identified with” FKD while discussing attacks on Jewish and LGBT targets and conducting surveillance for potential plots.54

Organized in 2018 by an individual who refers to himself as “Norman Spear” and “Roman Wolf,” The Base is a U.S.-based WSE group with international membership. Spear formed the group with a goal similar to that of AWD’s founders: preparing adherents of WSE ideology to commit acts of terrorism and participate in civil war.55 While Spear has attempted to publicly disavow violence – describing The Base as a “survivalism & self-defense network” – he has acknowledged that members are “militant” and seek to foment an insurgency. Spear has also tacitly justified the use of terrorism to achieve his movement’s goals. For example, he commented in a June 2018 Gab post: “It’s only terrorism if we lose—If we win, we get statues of us put up in parks.”56

The majority of the group’s activity takes place in the United States, where cells and members have been identified in Maryland, Georgia, New Jersey, Michigan, and Wisconsin. The group has held paramilitary “hate” camps in Georgia and elsewhere in the United States and has reportedly sought to hold similar camps in Canada.57 The group’s physical meetups have attracted at least one Canadian member who regularly traveled to the United States to participate.

Members explicitly advocate mass violence in their online communications. While The Base has not successfully executed a terrorist attack, members from Maryland and Canada were indicted in January 2020 in connection with a plot to stage an attack at a gun rights rally in Richmond, Virginia.58 Three other members were charged in Georgia with conspiracy to kill anti-fascist activists, while others have been charged for vandalizing synagogues in Michigan and Wisconsin.

White Nationalist and White Separatist Groups

In the United States, militant white nationalists and white separatists organize around one of two aims: the replacement of the current U.S. government with a white-dominated regime, or the creation of a new white state in the United States. The most notable group in the former category is Patriot Front, which seeks to transform the country into a white ethno-state. Despite a shared origin with AWD that traces back to Iron March, Patriot Front eschews overt violence.59 The group has relied on predominantly nonviolent demonstrations to gain publicity. However, Patriot Front targets ideological foes – including anarchists and other left-wing activists – with intimidation and threats of violence.

Factions of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) currently active in the United States are not as large or well-organized as earlier iterations of the Klan, but the movement continues to advocate for white power. Most contemporary KKK factions typically refrain from violence. But some, particularly the Loyal White Knights, the largest Klan group in the United States, repeatedly threaten violence against non-whites, and individual members have plotted terrorist attacks.60

Few significant white separatist WSE groups currently exist in the United States. The most prominent is the League of the South, though its ability to operate has declined since the violent clashes at the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, as well as due to the increasingly militant statements of its leadership. The group’s recent activity has consisted of protests and demonstrations. While these activities were largely nonviolent, several members have been arrested or convicted of violence at these events.61

In Europe, one of the most salient militant transnational white nationalist groups is the Nordic Resistance Movement (NRM). NRM is a Sweden-based group that advocates for a halt to non-white immigration to Nordic countries and favors the creation of a single Nordic nation.62 The group has tried to organize as a political party in Sweden.63 NRM also has offshoots in Norway, Finland, Iceland, and Denmark, though Finland officially banned it.64 Members have been involved in bombings as well as street brawls with opposition groups.65

White Power Skinheads

Major transnational white power skinhead groups include the British-origin Blood & Honour (B&H), the affiliated Combat 18 (C18), and the U.S.-origin Hammerskins. B&H originated as a loose association of white power music groups and affiliated racist skinheads in the United Kingdom in the 1980s.66 While expanding into an international movement, the group splintered several times. B&H now claims affiliates throughout Europe, the Americas, Australia, and New Zealand.67 Several countries have proscribed the group, including Germany, Spain, Russia, and Canada.68

C18 is sometimes described as B&H’s armed wing.69 The “18” in the group’s name is a reference to Adolf Hitler (“A” is the first letter of the alphabet, while “H” is the eighth). C18 has carried out murders and bombings in North America and Europe, among other violent acts.70 The group is thought to have a leaderless structure.71

Logo of a U.S.-origin skinhead group, the Hammerskins.

The Hammerskins originated as a nationwide umbrella for U.S. skinhead groups. While the primary central organization, Hammerskin Nation, is now defunct, Hammerskins chapters continue to operate throughout the United States, and there is at least one annual national event, a music festival known as Hammerfest.72 The current level of organization beyond local chapters is unclear, as skinhead activity primarily takes place underground, and two major websites associated with the Hammerskins are now defunct. Hammerskins crews have also been established in Europe and Australia. Supporting organizations made up of prospective members go by the name Crew 38.73 The rest of the American skinhead movement is organized primarily into small regional and community groups, though at least one national offshoot of the Hammerskins, the Vinlanders Social Club, remains active.74 White power record labels and inter-group associations are major mechanisms that help provide a limited degree of cohesion to the current movement.

U.S.-based skinhead groups serve as a source of recruits for organized WSE groups, including the Rise Above Movement (RAM), an independent WSE group. While RAM has shed some overt cultural markers of the WSE skinhead movement (describing itself as the “Premier MMA [mixed martial arts] club of the Alt-Right”), it has recruited from California’s racist skinhead scene, including members of the Hammerskins, and retains the movement’s focus on street fighting.75 The group has participated in numerous brawls during political protests in California and elsewhere in the United States.76 RAM emphasizes physical fitness and martial arts to prepare members to fight opponents. The group markets its clothing brand, The Right Brand, to gain a broader following.77 RAM has international aspirations. In spring 2018, the group’s leadership traveled to Italy, Germany, and Ukraine to establish connections with a variety of European groups, including the Ukraine-based Azov Battalion (discussed further below).78 Members of RAM traveled to Budapest in February 2020 to participate in a Hungarian nationalist holiday alongside WSE individuals from Hungary, Germany, Russia, Bulgaria, France, and other European countries.79 More recently, RAM may have rebranded, changing its name to Revolt Through Tradition.

Domestic Activities

Violent Activity

American WSE groups are divided over the use of violence. Some view terrorism and killing as essential tools for achieving their goals. Others are more commonly implicated in unplanned assaults and murders.80 Still others view violence as a potential threat to the movement’s growth and carefully restrict their activities to threats and intimidation.

Most successful American WSE terrorist attacks have been perpetrated by lone attackers, though several disrupted plots have involved small cells.81 The groups most closely associated with these plots include AWD, its offshoots, and The Base. Skinhead groups are behind murders and assaults, generally motivated by race, ethnicity, religion, or other identity. Casual violence remains an important element of their subculture.82

Some WSE groups seek out confrontation at rallies and demonstrations, with the intention of engaging in street brawls. Violence at such events can originate with not only WSE groups but also their opponents, whether anti-fascist protesters or other opposition groups.83 It can frequently (though not always) be difficult to discern who instigated a fight and who engaged in legitimate self-defense. Some WSE groups that eschew most forms of violence do prepare for, and intentionally encourage or incite, street brawls. Street violence of this nature may be welcomed but not intentionally plotted beyond establishing conditions under which it is likely to occur. Multiple WSE groups notably arrived at the 2017 Unite the Right Rally anticipating and prepared for violence, armed with makeshift weapons and shields. These groups included the League of the South, one of whose leaders aggressively charged into a group of counter-protesters, and RAM, whose members were later convicted of conspiracy to riot for assaulting opposing protesters in Charlottesville and also during protests in Huntington Beach and Berkeley, California, in 2017. In those cases, RAM members trained for and anticipated violence before the protests and afterward openly celebrated their assaults on opposition activists.84

In addition to physical violence, WSE groups frequently use intimidation tactics, including property destruction and physical intimidation. Patriot Front has engaged in such “gray-area” behavior, as have the Loyal White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. Accelerationists, typically associated with more extreme violence, have also engaged in this activity. Richard Tobin, an alleged member of The Base, was charged with coordinating the vandalism of synagogues in Michigan and Wisconsin via online platforms and encrypted communications with two members of The Base in the Great Lakes region.85

Training for Violence

Members of WSE groups may also participate in paramilitary training camps or other activities that prepare adherents for violence. The level of preparation can vary from defensive tactics and the construction of makeshift shields, as executed by the Shield Wall Network, to shooting drills.86 Both AWD and The Base have held training camps for their members – referred to by The Base as “hate camps” – throughout the United States, including in Nevada, Georgia, Illinois, and Washington.87

Members of Atomwaffen Division gather for a three-day hate camp in Nevada in January 2018, dubbed “Death Valley Hate Camp.”

Hate camps represent a critical step for this newer generation of extremists, serving as a steppingstone from online activity (for so-called “keyboard warriors”) to real-world action. ProPublica reported on an Atomwaffen hate camp held in southern Illinois in 2017:

At least 10 members from different states attended, with some driving in from as far away as Texas, Kansas, Oklahoma and New Jersey. In the Pacific Northwest, cell members had converged on an abandoned cement factory, known as “Devil’s Tower” near the small town of Concrete, Washington, where they had screamed “gas the kikes, race war now!” while firing off round after round from any array of weapons, including an AR-15 assault rifle with a high capacity drum magazine. The training sessions were documented in Atomwaffen propaganda videos.88

These camps allow groups to engage in tactical training, hold sensitive offline discussions, build group trust, and further indoctrinate members. The camps also provide raw footage for future video or photographic propaganda, which frequently highlights firearms training and other group activities.

Transnational Connections

WSE groups are connected to a global WSE movement through shared ideologies but cement those ties through joint transnational activities, including participation in protests, historical commemorations, entertainment events, conferences, and – occasionally – combat. Some groups even establish chapters or operate in multiple countries.89 These transnational activities are meant to further connect organizations and adherents or to raise public awareness of WSE ideologies and recruit new members. The result is the creation of a larger, more cohesive global movement. This section introduces some of the activities and events that foster these connections.

Protests, Demonstrations, and Festivals

Public-facing protests and demonstrations, which connect members and bring attention to the WSE movement, are a significant part of the movement’s transnational activities. In addition to raising awareness of WSE ideology, protests and demonstrations serve as networking events. Protests and demonstrations are common in Central and Eastern European countries with particularly active domestic WSE scenes, such as Germany, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Ukraine.

Key dates related to white supremacist extremism – particularly those relevant to Nazism and similar political movements – often serve as the basis for demonstrations, protests, and festivals that draw international attendance. Examples include:

- Shield and Sword Festival. Perhaps the most notable historical event celebrated by WSE groups is April 20, Adolf Hitler’s birthday. In 2018, the occasion inspired a large festival called Schild und Schwert (“Shield and Sword”) in Ostritz, Germany. This event was held again in June 2019.90 The festivities drew attendees from across Germany as well as from the Czech Republic and Poland.91

- Lukov March. The ultranationalist political party Bulgarian National Union hosts a march each February in Sofia, Bulgaria, to commemorate the assassination of Hristo Lukov, a Bulgarian nationalist who worked with the Nazi regime during World War II.92 The 2018 Lukov March attracted over a thousand participants, including several members of the NRM. The 2019 march attracted an estimated 2,000 people, including members of the NRM and other foreign WSE organizations.93 The leader of NRM’s Swedish branch, Per Sjogren, said of the 2019 march: “We want to get in contact with other nationalists in Europe, as we strongly believe that free, independent countries are very important. We want to regain the power from the globalists—the people who are running the EU, the people who are devastating Europe.”94 The 2020 Lukov March was canceled after Bulgaria’s Supreme Administrative Court upheld a ban issued by the mayor of Sofia, who cited concerns about antisemitism and hate speech.95

- Festung Budapest/Day of Honor. Various foreign WSE groups attend Festung Budapest, also known as the Day of Honor, commemorating the 1945 Siege of Budapest fought between Axis and Soviet forces in World War II.96 In 2019, event organizers – the Hungary-based WSE group Légió Hungária – claimed that roughly 600 people attended, including WSE organizations from abroad. NRM leaders Simon Lindberg and Matthia Deyda were featured speakers. Photos show flags and symbols of other transnational and foreign WSE organizations, including the Hungarian Hammerskins and the Hungarian Blood & Honour/C18.97

Entertainment Events

International entertainment events unite WSE groups across borders and offer networking, fundraising, and recruiting opportunities for participants. Entertainment events are among the largest events in the WSE sphere, particularly in Europe. Currently, there are two major themes: music and MMA.

Neo-Nazi and National Socialist black metal (NSBM) concerts provide a platform for songs and lyrics that promote violence toward minorities, romanticize Nazi Germany, and champion WSE beliefs.98 Many of these concerts occur in Central and Eastern Europe, particularly in Germany and Ukraine.99

In Ukraine, tickets for WSE concerts are available to the public. The venues are relatively large, holding up to 1,500 people.100 One notable NSBM concert, the Asgardsrei festival, occurs every December in Kyiv. The 2019 festival hosted NSBM bands from across Europe and beyond, including Goatmoon from Finland, M8L8TH from Russia, and Evil from Brazil. A total of 15 bands from eight different countries performed.101 Asgardsrei was originally founded by Russian WSE Alexey Levkin, who moved to Ukraine to fight with the Azov Battalion and brought the festival with him.102 Asgardsrei now plays a large role in the Azov movement’s publicity efforts. Olena Semenyaka, the international secretary for Azov’s political wing, said that Asgardsrei “helps us to develop and build our international fanbase, our support base. Members of [international] political organizations attend this conference and attend this festival.”103

International members of the WSE movement, such as Faroese Frodi Midjord, a key contributor to alt-right publication Counter Currents and founder of the Scandza Forum, likely attended the 2018 Asgardsrei concert.104 Similarly, evidence suggests that American members of AWD attended the event.105 In addition to Asgardsrei, Kyiv also hosts Fortress Europe at the same venue as Asgardsrei: the Bingo club. Initially scheduled for May 22–23, 2020, the event was postponed to June 11–12, 2021. Like Asgardsrei, tickets to Fortress Europe are available for public purchase, with no vetting required. The lineup scheduled for 2021 includes M8L8TH, the Russian NSBM band that played at Asgardsrei.106

The AWD flag (bottom right) seen at the Asgardsrei concert in Ukraine as Russian NSBM band M8L8TH plays.

In Germany, WSE concerts and other music events have increased in frequency and attendance. The German government reported 199 neo-Nazi and WSE-related music events in 2015, 223 events in 2016, and 259 events in 2017.107 Some of Germany’s largest WSE concerts take place in the southeastern state of Thuringia.

MMA events play a smaller but growing role in the movement. An MMA “fight night” was held prior to the Asgardsrei concert in Kyiv, and the 2018 Shield and Sword festival featured MMA fights held by a German organization. The festival organizer said that its goal was to provide an event that “united everything: politics, art, music, and sports.”108

Conferences

WSE groups and individuals often participate in international conferences catering to the broader white identity politics movement, including nonviolent groups. Conferences serve as networking events and allow for the exchange of ideas and tactics. Notable international fora that have attracted transnational WSEs include the London Forum and the annual Scandza Forum. Though these conferences attract a broad cross-section of participants, some speakers and participants have belonged to violent groups or themselves have advocated for violence.

The London Forum was established in 2011 by Jeremy Bedford-Turner, a former member of the British political party National Front.109 Many speakers are controversial yet nonviolent. However, at the London Forum, Swedish nationalist Kai Murros advocated for violent revolution in the United Kingdom, specifically through attacks on academics and universities.110

Transnational conferences and fora are important for emerging groups in the global WSE movement. In August 2019, Nova Ordem Social (NOS), a far-right organization in Portugal, held a small conference attended by around 65 people.111 Despite the small number of attendees, representatives of at least six other European WSE groups attended, including Italy-based Autonomia Nazionalista, the French Nationalist Party, the Bulgarian National Resistance, Germany-based Die Rechte, and Poland-based Obóz Narodowo-Radykalny (ONR).112

Foreign Fighters and the Ukrainian and Russian Nexus

Ukraine and Russia are important drivers of some transnational WSE activity. The civil war in Ukraine’s Donbas region attracts fighters from Europe and North America, who join the ranks of Ukrainian military and paramilitary groups. Excluding Russians, more than 2,200 foreign fighters have participated in the Ukrainian conflict between 2014 and 2019, including 35 from the United States.113

The Azov Battalion is a Ukrainian nationalist organization formed in 2014 to combat the Russian-backed separatist movement in eastern Ukraine. As a military unit, the Azov Battalion has integrated into the Ukrainian National Guard as the Azov Regiment. The Azov Regiment has clear connections – through both origin and leadership – with the National Corps political party and the paramilitary group National Militia, which remain independent of the Ukrainian state.114 The three groups are considered by experts to be elements of a single movement, though there are disagreements about the degree of interconnectedness among them.115

National Corps and the Azov Battalion have engaged with ultranationalist groups in the United States and Europe, and they communicate with multiple extremist groups in the United States, including RAM.116 Statements by the leadership of National Corps suggest the group seeks to export its ideology, espousing a modern “Reconquista” that begins with Ukraine and Eastern Europe. As a spokesman described it, the goal of this Reconquista is to “defend not only the Ukrainian nation, national identity, but also the Slavic element, the European element, and in the end—the white race.”117 The Azov Battalion and National Corps have sought to recruit fighters from Europe and the United States.

Right Sector forms another element of the Ukrainian nexus. The organization’s leadership seems to share the vision of a European Reconquista espoused by National Corps leaders.118 Unlike the Azov Regiment, Right Sector’s military arm has not been fully absorbed into the Ukrainian military. The group’s factions maintain a somewhat combative stance toward the central government and have been targeted in government crackdowns. Right Sector continues to attract foreign fighters from Western Europe and America, some with WSE ideologies or involvement in the movement.119

Despite reduced violence following the 2015 Minsk II Accords, Ukraine remains an attractive destination for WSE fighters seeking combat experience, including Americans. In fall 2019, the leader of The Base described the conflict as an opportunity to train group members and gain combat skills from the front lines.120 Two AWD members were deported from Ukraine in October 2020 after having traveled there with the intention of joining the Azov Regiment.121

Russian extremist groups, most notably the Russian Imperial Movement (RIM), work with the global WSE movement. RIM is an ultranationalist movement that embraces monarchism. It maintains a paramilitary arm, the Imperial Legion, that has fought in Ukraine.122 Despite its monarchist stance, RIM is tolerated by Moscow, likely because the recruitment of Russians to fight in Ukraine serves the Kremlin’s interests. The group works with other European WSE groups, including NRM. Two members of NRM who attempted to bomb a home for asylum seekers trained at RIM’s “Partisan” paramilitary training course. The leader of RIM has also spoken at an NRM summit and donated money to the party.123 RIM co-organized a 2015 conference in the Russian city of St. Petersburg that U.S. white power activists attended. RIM also met with Matthew Heimbach, leader of a now-disbanded U.S.-based WSE group called the Traditionalist Workers Party.124 In April 2020, the U.S. State Department listed RIM as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT), the first WSE group to be designated as such in U.S. history. State’s designation notes that RIM has trained European WSEs who then committed acts of terrorism in their own countries.125

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

In the United States and internationally, the WSE threat continues to grow, and attacks have occurred even during the COVID-19 pandemic. The WSE movement thrives in the current political environment, which is increasingly prone to various extremist ideologies. There are concrete policies that can be leveraged to reduce this threat. In countering domestic threats of violence, however, the U.S. government must ensure that it protects relevant civil liberties and maintains political neutrality.

Consider Designating WSE Groups as Terrorist Organizations

Designating extremist groups as terrorist organizations is a step that the departments of State and the Treasury do not take lightly. The 2020 designation of RIM as an SDGT was a significant step in countering WSE groups. It is worth considering further designations of violent WSE groups and actors that meet the criteria to be listed as SDGTs or Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs).126

Consider a Domestic Designation Statute

A statute that allows for designation of domestic violent extremist organizations should be considered. Rather than advocating for or against it, this section describes the benefits and costs of such an approach.

The creation and even-handed employment of such a statute may be the most direct way to address and interdict funding for domestic violent extremist organizations. Such designation would potentially criminalize the financing of these organizations and enable authorities to freeze assets the organizations may already hold.

However, such a domestic statute would raise civil liberties concerns. One major concern would be ensuring that this statute is ideologically neutral in conception and application. Designations should correspond to the threats that groups pose, not the ideas they espouse. A domestic designation statute that targets groups espousing only certain ideologies may heighten the risk of violence. The perception of designation bias may become a rallying cry, drawing more members to violent extremism. As such, this statute must be clear about the predicate acts that trigger designation. Vague or imprecise language would render the statute vulnerable to legal challenges to both its adoption and its enforcement. The threshold for designation should be high: For a group to be designated, it must pose a legitimate threat to the lives of others. Finally, the statute must include a redress mechanism. The consequences of designation are severe and demand an opportunity for appeal.

Map WSE Groups and Their Finances

A dearth of knowledge about how WSE organizations are funded and structured hampers efforts to counter their financing. Accordingly, it is important to deepen our understanding of the organizational structures and funding mechanisms common to domestic violent extremist organizations.

The consensus among experts studying domestic violent extremism is that these groups are relatively fluid and devoid of organizational structure. This may be so. However, these groups may have a hidden hierarchy or organizational structure. Moreover, in the digital age, fluid organizational structures can quickly harden into more concrete ones. This increases the need to unearth concealed organizational structures. Such understanding can help authorities proactively disrupt sources of funding and mitigate the potential for harm. Further research in this area is needed.

Conduct Messaging Campaigns Aimed at Discrediting WSE Groups

The United States has a history of devoting resources to messaging efforts designed to discredit extremist groups. While Washington’s record of discrediting jihadist groups can most charitably be described as mixed, it would be foolish to cede the territory of messaging to WSE groups. Propaganda and messaging constitute an inherent part of any significant conflict. One approach to countering WSE messaging might include de-bureaucratized teams – or “startups within government” – with flexibility in the messaging sphere. In the present case, this could be accomplished by a nimble unit of communications professionals and intelligence officers monitoring WSE propaganda and generating real-time counter-messaging content that exposes falsehoods in WSEs’ messaging and provides facts that discredit the movement. Such a model would inhibit WSE ability to enter new communication spaces unchallenged.127

The benefit of a “startups-within-government” approach is that government messaging efforts tend to be overly risk-averse. Most startups in the commercial sphere fail within their first three years of existence, and that is a good thing: Those that survive the Darwinian process confronting new businesses often go on to become highly profitable and accomplished. A startups-within-government model would accept the near certainty of failed experiments, with the understanding that de-bureaucratized cells that do not fail in a competitive environment are more likely to achieve an outsized impact.

Work With Technology Companies and Social Media Platforms

Extremists use social media and technology platforms to disseminate materials and recruit. In the past, WSE attackers have posted manifestos online prior to carrying out attacks. There may be better ways to identify danger signs and alert authorities if danger appears likely or imminent. And platforms where WSEs may attempt to spread violent ideologies and recruit should be monitored. Indeed, one increasingly important space for WSE recruitment appears to be videogames. Partnerships between large and small technology companies may help create a more comprehensive effort, including by providing smaller companies access to resources.

Collaboration between the U.S. government and technology companies has often been hampered by technology companies’ mistrust of government intelligence-gathering, as well as concerns about user privacy. The U.S. government should address WSE activity in a manner consistent with these concerns. Continuing dialogue about content takedowns – regardless of the ideology of the content – is crucial. The success of the dialogue will depend on the ability of participants to approach extremism with the appropriate level of context and expertise and without bias. To this end, one critical recommendation is to include people with a diversity of perspectives in these discussions, including those skeptical of content takedowns due to concerns related to protecting speech and expression.

Work With International Partners

Since the WSE movement is global, Washington must collaborate with international partners to study groups and individuals with connections to WSE militancy. WSE groups seek to establish cross-border links with foreign counterparts, and some even establish overseas chapters or operate in multiple countries. They can inspire and motivate others across the globe to carry out attacks. The U.S. government should study and prepare for potential new avenues of internationalization and transnational collaboration in the WSE sphere. Such understanding and awareness would better prepare U.S. law enforcement and intelligence to halt or respond to acts of WSE violence.

Study Reciprocal Radicalization and Fringe Fluidity

In the current polarized climate, opposite extremes tend to radicalize both sides and provide average people a reason to drift toward extremes. Theories of reciprocal radicalization and fringe fluidity are therefore highly instructive. Reciprocal radicalization suggests that growing power and success of groups aligned with one extremist ideology will fuel recruitment and encourage activity by groups of ostensibly opposing ideologies. Interactions between groups locked into reciprocal radicalization often result in “a bizarre mixture of cooperation, competition, and overt fighting between different groups.”128 Another relevant dynamic is fringe fluidity.129 This is a radicalization pathway in which individuals transition from one form of extremism to another. Fringe fluidity demonstrates how extremists prioritize common grievances, goals, and enemies even when their overarching ideologies conflict.130 Brenton Tarrant, the March 2019 Christchurch mosque killer, is one recent example. Tarrant shifted between several extremist ideologies, ultimately declaring himself an ecofascist at the time of his attack.131

In an era of political polarization, extremists may seize the opportunity to draw recruits and mobilize from a growing menu of overlapping and sometimes conflicting militant ideologies, making fringe fluidity an increasingly powerful force. Likewise, evidence of reciprocal radicalization among extremist groups demands attention, as extremists of one persuasion have no shortage of opposing forces to radicalize them. The U.S. government should devote resources to studying these phenomena.

Resist the Temptation to Pick Sides

In recent years, politicians have too often spoken on issues of extremist violence with ambiguity because of partisan considerations. Political leaders must recognize the role they may play in furthering extremist narratives. Choosing a side serves to prioritize goals and enemies as the extremists would. As political factions and movements in the United States resort to violence or the threat of violence to pursue objectives, the government must be unified and precise in its messaging: Political violence is completely intolerable in a democratic society.

Create Architecture for the Age of Mass Attacks

WSEs have in the past conducted mass attacks in public spaces, some of which have left significant numbers dead. Unfortunately, violent extremists of various ideological stripes, as well as non-ideological mass attackers, are certain to strike again. In too many attacks, man-made structures have aided attackers and worked against those trying to escape. Victims have been trapped by limited exits or prevented from securing rooms because doors do not lock from the inside. One solution is crisis architecture, an architectural paradigm that offers integrated tactical, psychological, and technological security measures while preserving function and aesthetics.132