October 22, 2020 | Insight

The Trump Administration’s High-Stakes Gambit to Curtail Rocket Attacks in Iraq

October 22, 2020 | Insight

The Trump Administration’s High-Stakes Gambit to Curtail Rocket Attacks in Iraq

In an unexpected announcement on October 10, a group of Iran-backed Shiite militia groups declared their intention to suspend forthwith their attacks on U.S. interests in Iraq, while conditioning the ceasefire’s continuance on the Iraqi government’s development of a plan for the withdrawal of U.S. troops. This unsolicited declaration followed the Trump administration’s equally unexpected threat on September 20 (delivered via a phone call from Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to Iraq’s President Barham Salih) to shutter the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad and launch large-scale military strikes against the militias if Iraq did not do more to prevent attacks on U.S. interests there.

For over a year and half, Iran-backed militias have regularly targeted the U.S. presence in Iraq with rocket and mortar strikes. Washington has absorbed these attacks without retaliating, except when the strikes crossed the red line of taking American life. Indeed, in the face of no fewer than 78 reported instances of indirect fire since May 2019 (as documented by the Foundation for Defense of Democracies), the Trump administration hit back only twice – in both instances after Americans were killed. The only exception to this pattern was the targeted killing of Qassem Soleimani, Iran’s terrorist mastermind, as well as his Iraqi counterpart, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, in Baghdad last January, which came in response to a militia-organized assault on the perimeter of the U.S. Embassy.

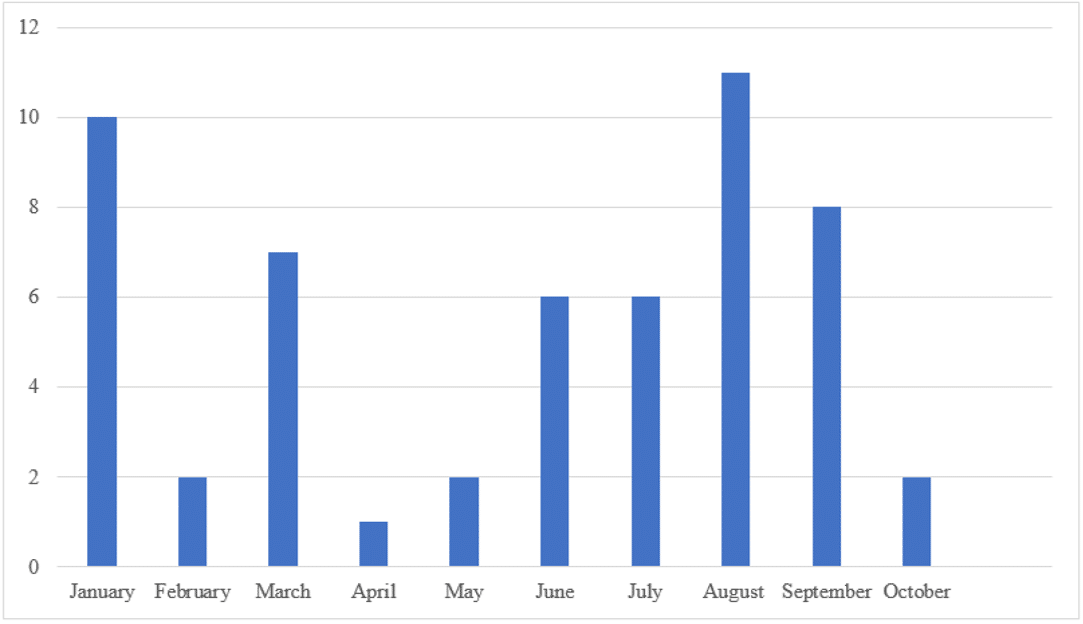

As the data below indicates, there have been at least 55 reported rocket and/or mortar attacks just this year against U.S. targets attributable to the militias. Just over a third of those attacks occurred in August and September alone – in the period leading up to and following the successful visit to Washington of Iraq’s new prime minister, Mustafa Al-Kadhimi. While the frequency of the attacks represented a clear escalation of efforts to harass the United States and embarrass Kadhimi, the vast majority involved low numbers of rockets per volley and the use of lower-end weapons, not the most deadly capabilities believed to be in the militias’ arsenals. None, fortunately, resulted in any U.S. casualties – though an errant attack on September 28 killed six members of an Iraqi family, including several children.

While the attacks have long been a source of tension in U.S.-Iraqi relations, the administration’s sudden threat to close the embassy and unleash a massive attack against the militias came as something of a shock. During Kadhimi’s Washington visit, he held what appeared to be extremely cordial meetings with both President Donald Trump and Secretary Pompeo, in which both sides reaffirmed their commitment to the U.S.-Iraq strategic partnership. In that context, Pompeo’s threat to abandon America’s diplomatic presence in Baghdad was a bolt from the blue that caught not only Iraqi officials, but many of their U.S. counterparts, by surprise.

The administration’s gambit carried significant risks for U.S. interests. U.S. military commanders have made clear that evicting the United States from Iraq has been among Iran’s top priorities. Being able to claim that its proxies had put the Great Satan’s agents to flight from Baghdad, 17 years after they entered as occupiers, would clearly be a major victory for Tehran. It would also be a massive blow to Kadhimi, who is as pro-Western a prime minister as Iraq has had since 2003, and who has staked his premiership on strengthening relations with America and reining in the militias. A large-scale U.S. assault on militia targets would also almost certainly sound the death knell for the U.S. military presence in Iraq and the viability of its ongoing counterterrorism operations there against the Islamic State (ISIS).

Despite these major risks, the administration’s threat may actually be paying off. It certainly triggered a panic amongst Iraq’s governing class and generated an unprecedented amount of political pressure aimed at stopping the militia attacks. Kadhimi, Saleh, and Foreign Minister Fuad Hussein repeatedly issued unambiguous public warnings about the potentially catastrophic consequences of an embassy closure on Iraq’s precarious political, economic, and security situation. They convened emergency meetings with other Iraqi political leaders. They bolstered the presence of Iraqi security forces in areas near the U.S. Embassy and made clear that units would be held accountable for failing to prevent attacks from their areas of responsibility. They reached out for support to foreign governments in Europe and the Gulf, while Hussein was dispatched to Tehran to convince the Iranians to back off. Powerful political factions and anti-American militias led by leaders such as Moqtada al-Sadr and Hadi al-Ameri felt compelled to issue statements decrying the embassy attacks as harmful to Iraq’s interests and demanding that they stop. All of which culminated in the decision by Iran’s most hardcore loyalists to issue their October 10 statement, in the name of the “Iraqi Resistance Coordination Committee,” declaring a suspension of attacks against U.S. interests.

How long the ceasefire lasts, if at all, remains to be seen. In light of the enduring enmity of Iran and its proxies to the U.S. presence in Iraq, not very long is probably the safest bet. To the extent that the administration’s precipitous threat was triggered by an immediate concern that Iran might seek to embarrass Trump by staging a major attack on the embassy before the U.S. elections, the calculations of both Washington and Tehran may well change after November 3. The United States should clearly be ready for all eventualities.

What lessons to draw from the high-stakes game of diplomatic poker triggered by the administration’s threat are not entirely clear. It may still be too early for any firm conclusions. On the one hand, if the United States were forced to carry out its threat by actually shuttering the embassy under fire, the potential harm to U.S. interests could well be severe – with Iran, the militias, and ISIS likely the only winners. The same can be said if the attacks had escalated and the administration did nothing, exposing its threat as an empty bluff.

On the other hand, it is indisputable that Pompeo’s dire warning concentrated the minds of Iraq’s elite on the dangers posed by militia attacks like no previous diplomatic overture had ever done. Confronted by what they clearly took to be a plausible U.S. threat not only to abandon Iraq, but possibly to burn it down on the way to the exits, the entire Iraqi political class, both pro- and anti-U.S.; the Iran-backed militias; and, importantly, Iran itself, reportedly including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, saw the better part of wisdom in seeking, at least temporarily, to defuse the situation by taking action to allay U.S. concerns.

Ideally, of course, U.S. policy in Iraq would not be dependent on making threats that, if implemented, would risk doing grievous harm to important American interests. Washington would be better off taking a more balanced approach that sustains badly needed pressure on Iraqi politicians to take U.S. red lines seriously, while also closely coordinating with and supporting Kadhimi in implementing a methodical and comprehensive strategy to erode the power of the Iran-backed militias and the acute threat they pose not only to U.S. interests, but to Iraq’s independence and sovereignty as well.

APPENDIX: Documenting and Analyzing Recent Rocket and Mortar Attacks

Iran-backed militias’ rationales for rocket and mortar attacks against the U.S. presence in Iraq are diverse and have included: signaling resolve against attempts to deter militia activity; distinguishing themselves using violence to show loyalty to their patron; responding to localized action taken by Baghdad or Washington; and responding to the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” policy against their Iranian patron. However, as has been apparent in 2020, the root cause behind these attacks appears to be a desire to chip away at the American presence in Iraq and use limited force to beget a cycle of violence resulting in the eviction of U.S. forces.

A closer look at the data reveals that escalation does indeed correlate with changing political and military dynamics in Iraq. For the first half of 2020, for instance, attacks using rockets or mortars peaked in response to the U.S. use of force in Iraq in January and March – the latter of which was in response to the loss of American life.

But, more recently, other factors, such as the onset of the U.S-Iraq Strategic Dialogue and the Kadhimi visit to Washington, appear to have been opportune times for the militias to escalate. The second round of that dialogue, which was held in August during Kadhimi’s trip to the United States, coincided with the highest monthly total of rocket attacks on record this year – 11. Combining August and September, there have been 19 attacks against U.S. positions in Iraq, amounting to just over a third of the 55 attacks on record this year. What has decreased, however, is the actual number of rockets fired in a single attack, which only once (in September against Erbil International Airport) reached a rate last seen in March, which was six. By comparison, in March, militias once fired 33 Katyusha rockets in a single attack against an Iraqi base known to house U.S. forces.

For counting purposes, we define an attack as rocket or mortar fire toward U.S. facilities, persons, areas known to house them, or entities or areas affiliated with the broader U.S. presence in Iraq. Admittedly, a deeper analysis would require also incorporating the reemergence of roadside bombs, or improvised explosive devices, targeting the United States in Iraq – which took hundreds of American lives during the 2003–2011 Iraq War. Nonetheless, rockets and mortars, which function as part of the lower tier of Iran and its proxies’ military capabilities, deserve to be studied on their own and are accordingly recorded in the table and graphs below.

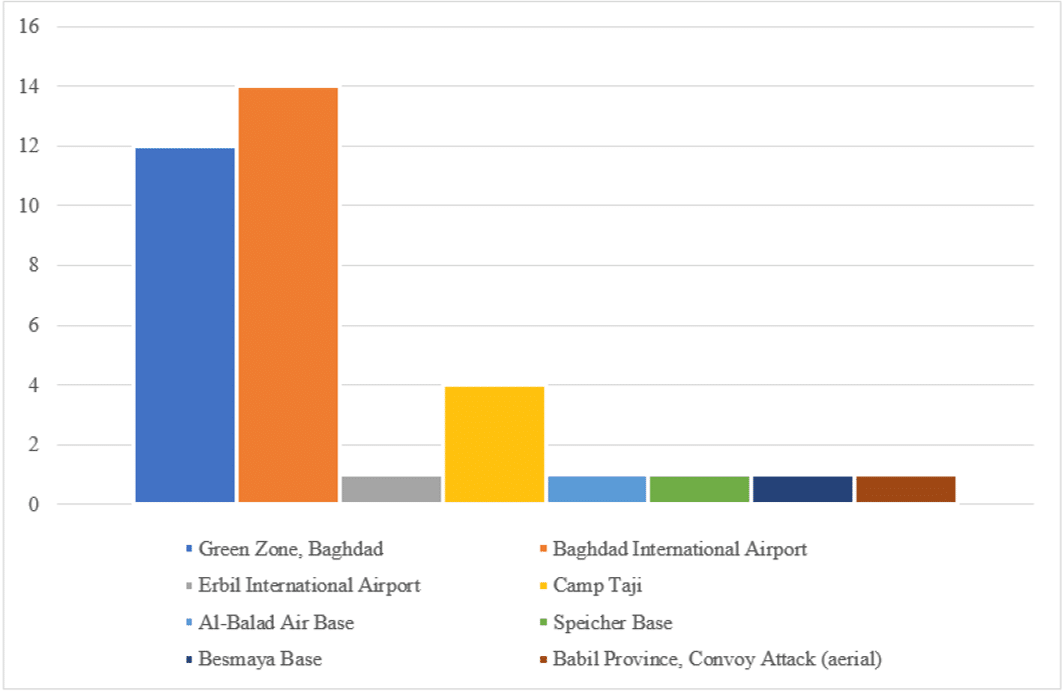

Figure 1 offers a compendium of attacks reported by at least one news source. It builds on previous research by the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, which analyzed and aggregated rocket and mortar attacks against U.S. positions in Iraq from May 2019 to April 2020, discovering 43 reported instances. The aim of both efforts is to introduce quantitative data into the conversation about escalation by Iran-backed groups in Iraq. Once that is achieved, members of the public can then draw their own inferences about things such as sourcing, injuries, or non-U.S. fatalities by following up on each documented attack. Figure 2 depicts the number of attacks per site, proving that Baghdad remains a key target for militias. Lastly, Figure 3 shows the distribution of attacks by month thus far in 2020.

Figure 1: Rocket and Mortar Attacks by Shiite Militias on U.S. Positions in Iraq, May 2020–Present

| Number | Date | Weapon(s) | Target/Location | U.S. Fatalities |

| 1 | May 6 | Katyusha rockets (3X) | Military complex near Baghdad International Airport | None |

| 2 | May 19 | Katyusha rocket (1X) | Green Zone, Baghdad | None |

| 3 | June 8 | Rocket (2X; later reporting claims 1X) | Baghdad International Airport | None |

| 4 | June 10 | Katyusha rocket (1X) | Green Zone, Baghdad | None |

| 5 | June 13 | Rockets (2X) | Camp Taji, Taji | None |

| 6 | June 15 | Rockets (3X) | Near Baghdad International Airport | None |

| 7 | June 18 | N/A (3 explosions heard, 4 rockets reported) | Green Zone, Baghdad | None |

| 8 | June 22 | Rocket (1X) | Baghdad International Airport | None |

| 9 | July 5 | Rocket (1X) | Green Zone, Baghdad | None |

| 10 | July 19 | Rockets (2X) | Green Zone, Baghdad | None |

| 11 | July 24 | Katyusha rocket (4X) | Besmaya Base, south of Baghdad | None |

| 12 | July 27 | Katyusha rocket (3X) | Camp Taji, Taji | None |

| 13 | July 27 | “Twin blasts” (assumed rocket, mortar, IRAM, or other indiscriminate fire) | Speicher Base, Salahaddin Province | None |

| 14 | July 30 | Katyusha rockets (2X) | Near Baghdad International Airport | None |

| 15 | August 3 | Rockets (2X) | Camp Taji, Taji | None |

| 16 | August 5 | Katyusha rocket (1X) | Green Zone, Baghdad | None |

| 17 | August 11 | Katyusha rocket (1X) | Green Zone, Baghdad | None |

| 18 | August 13 | Katyusha rockets (3X) | Al-Balad Air Base, Salahaddin Province | None |

| 19 | August 14 | Rockets (2X) | Camp Taji, Taji | None |

| 20 | August 15 | Katyusha rockets (3X) | Near Baghdad International Airport | None |

| 21 | August 16 | Katyusha rocket (1X) | Green Zone, Baghdad | None |

| 22 | August 18 | Katyusha rocket (2X) | Near Baghdad International Airport | None |

| 23 | August 27(28) | Katyusha rocket (3X) | Green Zone, Baghdad | None |

| 24 | August 29 | Rocket (1x) | Green Zone, Baghdad | None |

| 25 | August 30 | Katyusha rockets (2X) | Near Baghdad International Airport | None |

| 26 | September 6 | Katyusha rockets (3X) | Near Baghdad International Airport | None |

| 27 | September 10 | Katyusha rocket (1X) | Near Baghdad International Airport | None |

| 28 | September 15 | Katyusha rocket (1X) | Near Baghdad International Airport | None |

| 29 | September 16 | Katyusha rocket (1X) | Green Zone, Baghdad | None |

| 30 | September 20 | Katyusha rocket (1X) | Baghdad International Airport | None |

| 31 | September 22 | Mortars (3X) | Green Zone, Baghdad | None |

| 32 | September 28 | Katyusha rocket (1X) | Near Baghdad International Airport | None (6 Iraqi civilians killed) |

| 33 | September 30 | Rockets (6X) | Near Erbil International Airport | None |

| 34 | October 1 | Rocket or possibly rocket-propelled grenade (1X) | Convoy carrying equipment for the Anti-ISIS Coalition, Babil province | None |

| 35 | October 5

|

Rockets (2X) | Near Baghdad International Airport | None |

Sources: Hyperlinks to each attack included in table above.

Figure 2: Location of Shiite Militia Attacks on U.S. Positions in Iraq, May 2020–Present

Source: May 2020–present: Hyperlinks to each data point in Figure 1.

Figure 3: Shiite Militia Attacks on U.S. Positions in Iraq, January 2020–Present

Sources: For January–April 2020, see Behnam Ben Taleblu, “Collecting and analyzing Shiite militia attacks against the U.S. presence in Iraq,” FDD’s Long War Journal, May 5, 2020. (https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2020/05/collecting-and-analyzing-shiite-militia-attacks-against-the-u-s-presence-in-iraq.php). For May 2020–present, see hyperlinks to each data point in Figure 1.

John Hannah is a senior counselor at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), where Behnam Ben Taleblu is a senior fellow. They both contribute to FDD’s Center on Military and Political Power (CMPP) and Iran Program. For more analysis from John, Behnam, CMPP, and the Iran Program, please subscribe HERE. Follow FDD on Twitter @FDD and @FDD_CMPP and @FDD_Iran. FDD is a Washington, DC-based, nonpartisan research institute focusing on national security and foreign policy.