March 23, 2019 | FDD's Long War Journal

U.S.-backed forces declare end to Islamic State’s physical caliphate

March 23, 2019 | FDD's Long War Journal

U.S.-backed forces declare end to Islamic State’s physical caliphate

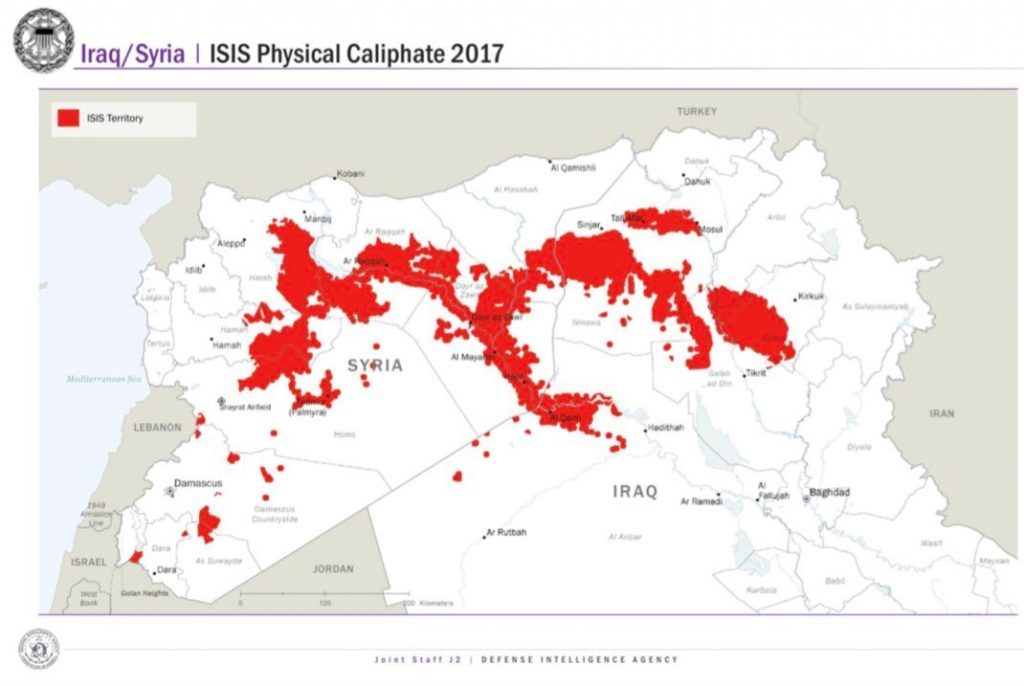

On Mar. 20, the Trump administration released this map depicting the Islamic State’s territorial caliphate as of early 2017. The group has lost control of this territory, but remains active in some of these areas.

The US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) declared today that the Islamic State’s caliphate has been defeated. In a statement posted online, the SDF announced the “destruction of the so-called Islamic State Organization and the end of its ground control in its last pocket in [Baghouz] region.” The SDF had battled the jihadists for control of Baghouz since early this year.

The first part of the SDF’s announcement is an exaggeration. The Islamic State’s organization has not been entirely destroyed. The group has lost its territory, meaning it can longer claim to rule over a physical caliphate. This has undoubtedly damaged the organization’s stature, making it less appealing to would-be recruits than at the zenith of its power in 2014 and 2015.

However, the group’s media machine shifted its messaging many months ago. Whereas the Islamic State once told followers that it was “remaining and expanding,” the jihadists now preach a message of resiliency and determination, claiming that their setbacks are a divine test.

The White House has celebrated the Islamic State’s loss of land, saying that the “territorial caliphate has been eliminated in Syria.” President Trump tweeted two maps commemorating the end of its “physical caliphate.”

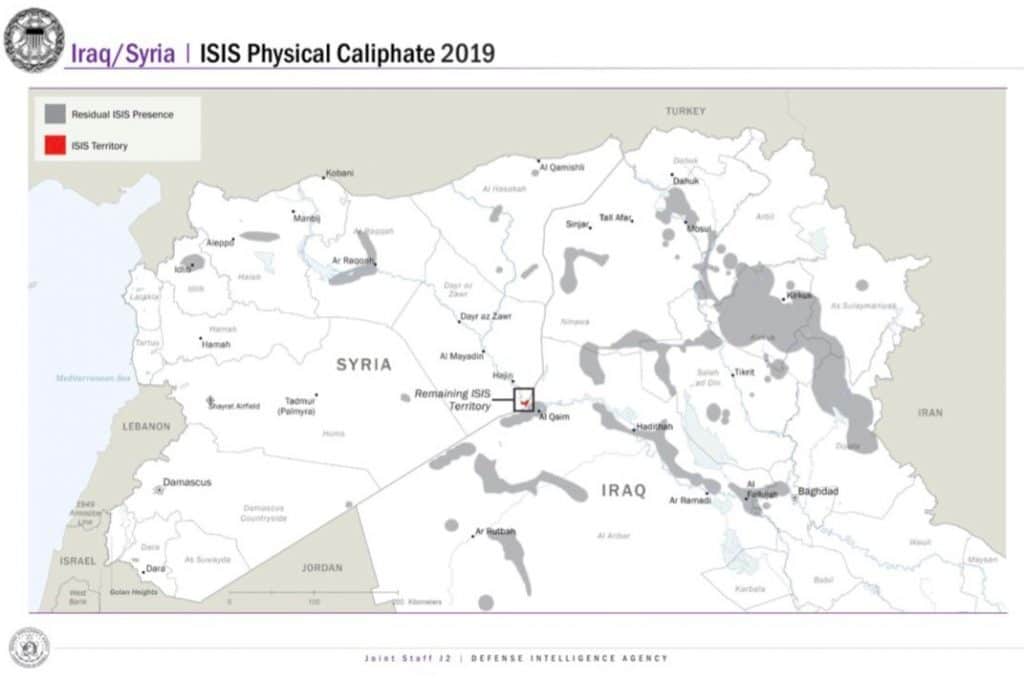

One of the maps (seen above), with large portions colored in red, purportedly shows the territory under the Islamic State’s control as of early 2017. The second map (below) shows the Islamic State’s territory as of Mar. 20, with only a small blotch of red around Baghouz, Syria. The SDF says that Baghouz is now out of the jihadists’ grip as well.

The Trump administration’s map shows gray areas where the Islamic State is thought to maintain a “residual” presence even after the fall of its territoral caliphate.

President Trump’s own maps illustrate that the Islamic State has not been entirely defeated. On the second, post-caliphate map, dark gray areas represent the territory where Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s loyalists maintain a “residual” presence. Significant ground inside Iraq is colored gray, including a swath of territory running through areas that are policed by predominately Kurdish forces. Small pockets of “residual” fighters are shown inside Syria as well.

The US is reportedly in the process of withdrawing most of the 2,000-plus troops who were stationed inside Syria as part of the anti-Islamic State mission. The Americans suffered significantly less casualties than partner Kurdish forces during the battles to eject the jihadists from their strongholds.

The SDF highlights its losses in its statement today. “This victory was extremely expensive, as more than 11 thousand martyrs of our forces, leaders and fighters, as well as civilian victims were the target of ISIS and more than 21 thousand fighters were sustainably injured,” the SDF says.

The idea of a caliphate in Iraq and Syria

The jihadists’ plan to build a caliphate first in Iraq and Syria has deep roots.

The Islamic State grew out of al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI), and its successor organizations. AQI was founded by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, an infamous mass killer who publicly swore allegiance to Osama bin Laden in 2004. Although al Qaeda’s senior leaders found Zarqawi to be unruly, and even suggested at one point that he step aside in favor of a more savvy battlefield commander, they backed his enterprise. Al Qaeda’s central management also emphasized the importance of establishing a caliphate based in Iraq.

In a July 2005 letter, Ayman al-Zawahiri chastised Zarqawi for indiscriminately killing Shiite civilians and celebrating gory executions, acts that Zawahiri warned could alienate the Muslim masses. Zawahiri deemed popular support crucial for the jihadists’ central goal, which was to “[e]stablish an Islamic authority or emirate, then develop it and support it until it achieves the level of a caliphate,” governing “over as much territory” as possible. Zawahiri advised Zarqawi that he should declare an Islamic emirate or caliphate in Iraq as soon as American forces were ejected. This jihadist state could then expand its operations into the neighboring countries and eventually declare war on Israel, Zawahiri wrote.

Under Zarqawi’s command, AQI merged with other groups to form the Mujahideen Shura Council (MSC) in early 2006. Zarqawi was killed in June 2006. In October of that same year, the jihadists announced the formation of the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) under the leadership of the “Emir of the Faithful,” a murky figure known as Abu Umar al-Baghdadi. Weeks later, Zarqawi’s successor, Abu Hamza al-Muhajir, declared his supposed fealty to al-Baghdadi, adding that the “first cornerstone of the Islamic Caliphate” had been laid with the formation of the ISI. Al-Muhajir served as the ISI’s war minister.

Although al Qaeda’s senior leaders may have been caught off-guard by the timing of the ISI’s announcement, they had already endorsed the idea in general and later claimed that its leaders remained loyal. In a Sept. 2006 interview, posted online just weeks prior to the ISI’s big announcement, Zawahiri explained that the jihadists were fighting to establish Islamic emirates in both Iraq and Afghanistan. These two countries would then become “the launching pad for [the] the defense of Islam and Muslims and a step toward the revival of [the] caliphate.” Although neither bin Laden nor Zawahiri knew Abu Umar al-Baghdadi personally, they repeatedly defended Baghdadi’s role as ISI chief in both public and private, arguing that al-Muhajir and others they trusted had vouched for him.

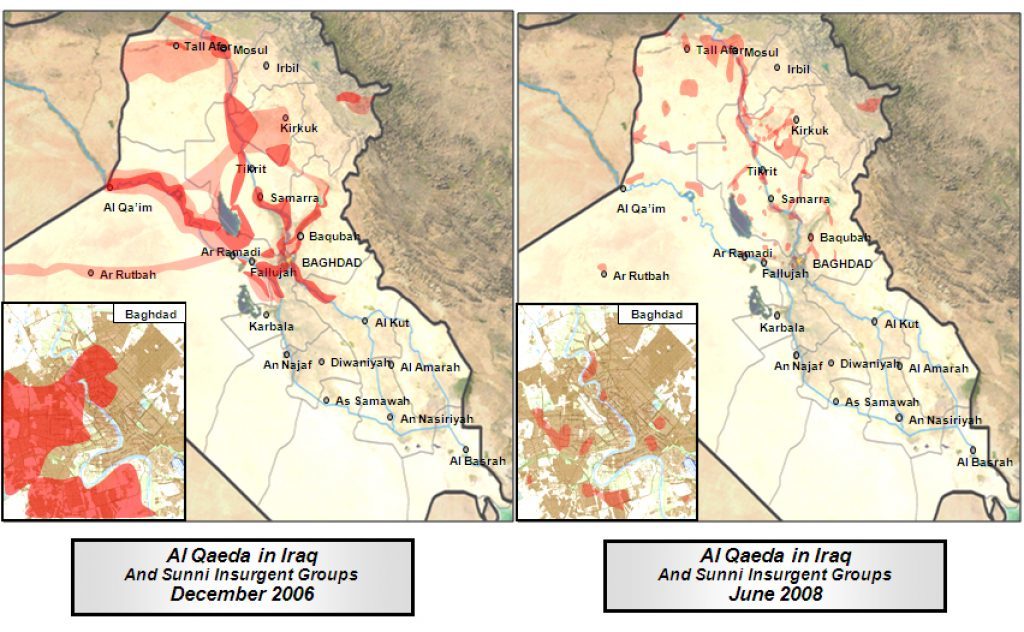

The ISI initially succeeded in capturing much territory in Iraq. In fact, President Trump’s maps are similar to ones produced by Multi-National Force – Iraq (MNF-IRaq), the US-led coalition that was responsible for rolling back the ISI’s emirate. Whereas the ISI conquered significant ground by late 2006, MNF-Iraq and Iraqi tribesmen had liberated many of these areas by 2008.

MNF-Iraq released maps such as these during the height of US involvement in the Iraq War. The maps are similar to those produced by the Trump administration more than a decade later, and highlight the longevity and depth of the jihadist’s project in Iraq.

In Apr. 2010, both Abu Umar al-Baghdadi and Abu Hamza al-Muhajir were killed in a joint US-Iraqi raid. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was named as the new head of the ISI.

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi has seldom made any public appearances. In a rare audio message posted online in May 2011, Baghdadi eulogized Osama bin Laden and vowed revenge for his death. Baghdadi referred to bin Laden as “our sheikh.” Baghdadi also addressed “our brothers in the Al Qaeda organization” and the “mujahid Sheikh Ayman al-Zawahiri,” as well as Zawahiri’s “brothers in the leadership” of al Qaeda. To Zawahiri and the others within al Qaeda, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi vowed: “You have in the Islamic State of Iraq a group of loyal men pursuing the endeavor of truth” and “they shall never forgive nor resign.”

By mid-2013, however, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and his ISI were openly defiant of Zawahiri. Baghdadi’s loyalists would argue that the ISI was never really a part of al Qaeda, a claim that is contradicted by much other evidence and not even logically consistent. Indeed, the ISI’s own videos celebrated the group’s role in al Qaeda’s network for years. Some of the videos featuring the ISI’s “martyrs” stressed that the organization’s men were bin Laden’s soldiers.

Regardless, Baghdadi defied Zawahiri’s order that he and his men remain in Iraq. The ISI expanded into Syria, rebranded itself as the Islamic State of Iraq and Sham (ISIS), and tried to subsume command of Al Nusrah Front. Although Al Nusrah was originally an arm of ISIS, its leader, Abu Muhammad al-Julani, rejected Baghdadi’s authority and reaffirmed his allegiance directly to Zawahiri. This was the beginning of a global rivalry, in which Baghdadi’s ISIS attempted to woo jihadists away from al Qaeda’s global network, while also recruiting others for its cause.

In Feb. 2014, al Qaeda’s general command disavowed Baghdadi’s ISIS, which was on the rampage at the time. Baghdadi’s men conquered large swaths of Iraq and Syria. In June 2014, ISIS declared itself to be a caliphate ruling over large parts of both countries. Baghdadi’s men rebranded their enterprise once again, saying that it was now simply the Islamic State.

The first map released by President Trump shows that, by early 2017, the Islamic State still controlled much of the territory it had seized at the height of its power. With the help of Iranian-backed militias and other forces, the US-led coalition liberated Mosul in mid-2017. By Oct. 2017, the SDF declared that Raqqa had been totally liberated.

The fall of the Islamic State’s twin capitals was a signficant blow to the organization, but many of its fighters and leaders relocated to other areas. The US-backed SDF offensive continued in Syria on and off during the months since Raqqa fall. Finally, the SDF claimed just today that the Islamic State no longer controls the last village that was part of its physical caliphate: Baghouz.

The Islamic State as an insurgency and global terror network

As the brief history above shows, the idea of a jihadist caliphate based in Iraq predates the Islamic State’s June 2014 declaration by years. It was an idea promoted by al Qaeda’s leaders. Beginning in 2013, Baghdadi tried to usurp al Qaeda’s authority over the global jihad. He was successful in some areas, but not nearly all. (Al Qaeda remains stronger in a number of countries to this day.)

It remains to be seen how strong the Islamic State still is inside Iraq and Syria, but the jihadists transitioned to an insurgency some months ago. While some of its forces fought to the bitter end in Baghouz and elsewhere, many others surrendered. This has caused an additional dilemma, as the US and its allies have to determine what should be done with those in custody. Jailbreaks and premature releases have fueled jihadist comebacks in the past.

Still other Islamic State fighters continue to carry out hit-and-run operations. This is especially true inside Iraq, where the jihadists maintain a signficiant footprint and regularly claim attacks on the Iraqi government, Kurds, tribesmen, and various Shiite parties. Official estimates, which should be taken with a grain of salt, indicate that the Islamic State still has thousands of fighters across Iraq and Syria.

Outside of those two countries, the Islamic State has so-called “provinces,” which remain active. The Khorasan “province” in Afghanistan and Pakistan continues to strike in Kabul and elsewhere. Other arms of the organization -in Libya, Somalia, Southeast Asia, West Africa, Yemen and elsewhere – are alive. Their overall strength is difficult to gauge, as there is an ebb and flow to their fight. But the Islamic State’s central leadership certainly sees the existence of these “provinces” as evidence that their international organization hasn’t been defeated.