March 27, 2024 | Memo

Much Ado About ‘Somethings’

China-Linked Influence Operation Endures Despite Takedowns

March 27, 2024 | Memo

Much Ado About ‘Somethings’

China-Linked Influence Operation Endures Despite Takedowns

Executive Summary

Beneath a video on Facebook about the war between Israel and Hamas, Lamonica Trout commented, “America is the war monger, the Jew’s own son!” She left identical comments beneath the same video on two other Facebook pages. Trout’s profile provides no information besides her name. It lists no friends, and there is not a single post or photograph in her feed. Trout’s profile photo shows an alligator.1

Lamonica Trout is likely an invention of the group behind Spamouflage, an ongoing, multi-year influence operation that promotes Beijing’s interests. Last year, Facebook’s parent company, Meta, took down 7,704 accounts and 954 pages it identified as part of the Spamouflage operation, which it described as the “largest known cross-platform influence operation [Meta had] disrupted to date.”2 Facebook’s terms of service prohibit a range of deceptive and inauthentic behaviors, including efforts to conceal the purpose of social media activity or the identity of those behind it.

This research report documents a previously unrecognized component on Facebook of Spamouflage, which operates over 450 pages and user profiles, including Lamonica Trout, as part of a coordinated effort to promote anti-American and anti-Western narratives.3 One hub of this activity is the community page known as “The War of Somethings,” which has around 2,000 likes and 3,000 followers — although many of those are likely to be no more real than Lamonica Trout.

The broader War of Somethings (WoS) network, so dubbed because all the Facebook pages and user accounts in the network are connected to “The War of Somethings” page,4 behaves very similarly to previous Spamouflage campaigns. The WoS network has targeted Guo Wengui, a wealthy Chinese businessman in exile, who is also a frequent target of Spamouflage. Previous analyses named the group Spamouflage because it posts apolitical content to camouflage its political agenda, a tactic that the WoS network also employs. Like Spamouflage, the WoS network is active during the workday in China and uses inauthentic accounts, including invented personas and hijacked accounts, to promote its content. For these reasons and others, the WoS network is very likely a part of Spamouflage.

To date, the WoS network appears to have had almost no reach outside of its own echo chambers. Yet previous Spamouflage campaigns have broken out to wider audiences. Prominent individuals with a record of hostility toward the United States, such as Venezuelan Foreign Minister Jorge Arreaza and British parliamentarian George Galloway, have shared Spamouflage content with their numerous followers.5

As of July 2023, and possibly earlier, the WoS network has posted content explicitly related to the upcoming U.S. elections, a sign that Spamouflage may be preparing to interfere in the elections.6 To help prevent such manipulation, the authors have shared the data from this paper with Meta to facilitate enforcement of Facebook’s terms of service.

Though Spamouflage operates on other platforms, this report focuses on its Facebook activity. Its Facebook network may actually be larger than what is documented. Leveraging the information below, social media companies with access to internal data can better assess the full scale and scope.

Spamouflage and other enduring influence operations demonstrate that social media takedowns are necessary, but not sufficient, to combat foreign malign influence operations. The federal government also has a role to play: It should send clear and consistent messages to China and other state sponsors of such operations that there will be a price to pay for attempts at manipulating U.S. public opinion.

Who is Spamouflage?

Social media analytics firm Graphika first documented Spamouflage in 2019.7 Initially, the operation used primarily Chinese language content to attack Guo Wengui and Hong Kong protesters opposing Beijing’s control.8 In 2020, Spamouflage began operating in English and criticizing U.S. foreign policy, America’s COVID-19 response, racial tensions, and U.S. scrutiny of TikTok.9

Spamouflage initially achieved little to no reach outside its own network.10 That changed in the second half of 2020, when Twitter accounts of Chinese diplomats, Huawei Europe, Latin American news stations, politicians from Chile, Pakistan, and the United Kingdom, and a range of other influential figures and organizations began sharing its content.11

Since that time, social media platforms have repeatedly attempted to take down Spamouflage’s networks. In January 2023, Google’s Threat Analysis Group reported it had disrupted 50,000 instances of Spamouflage activity across YouTube, Blogger, and AdSense.12 In the same year, as noted, Meta took down 7,704 Facebook accounts and 954 Facebook pages and called Spamouflage the “largest known cross-platform influence operation [Meta had] disrupted to date.”13 Despite these efforts, Spamouflage has endured and continues to push out new content.14

Researchers from Meta and reporter Adam Rawnsley of Rolling Stone helped unmask the people behind the operation, connecting Spamouflage to the Chinese Ministry of Public Security’s “912 Special Project Working Group.”15 They observed overlapping content in Meta’s reporting on Spamouflage and a U.S. Department of Justice criminal indictment filed against members of the Chinese working group.16

Casting America as a Nation in Crisis at Home and Reckless Abroad

The WoS network posts text, videos, political cartoons, photographs, and news articles criticizing U.S. domestic and foreign policy in a manner consistent with Chinese Communist Party (CCP) positions and posts content about the 2024 U.S. elections. The network seeks to portray the United States as a society in crisis whose government neglects the population while pursuing reckless foreign adventures.

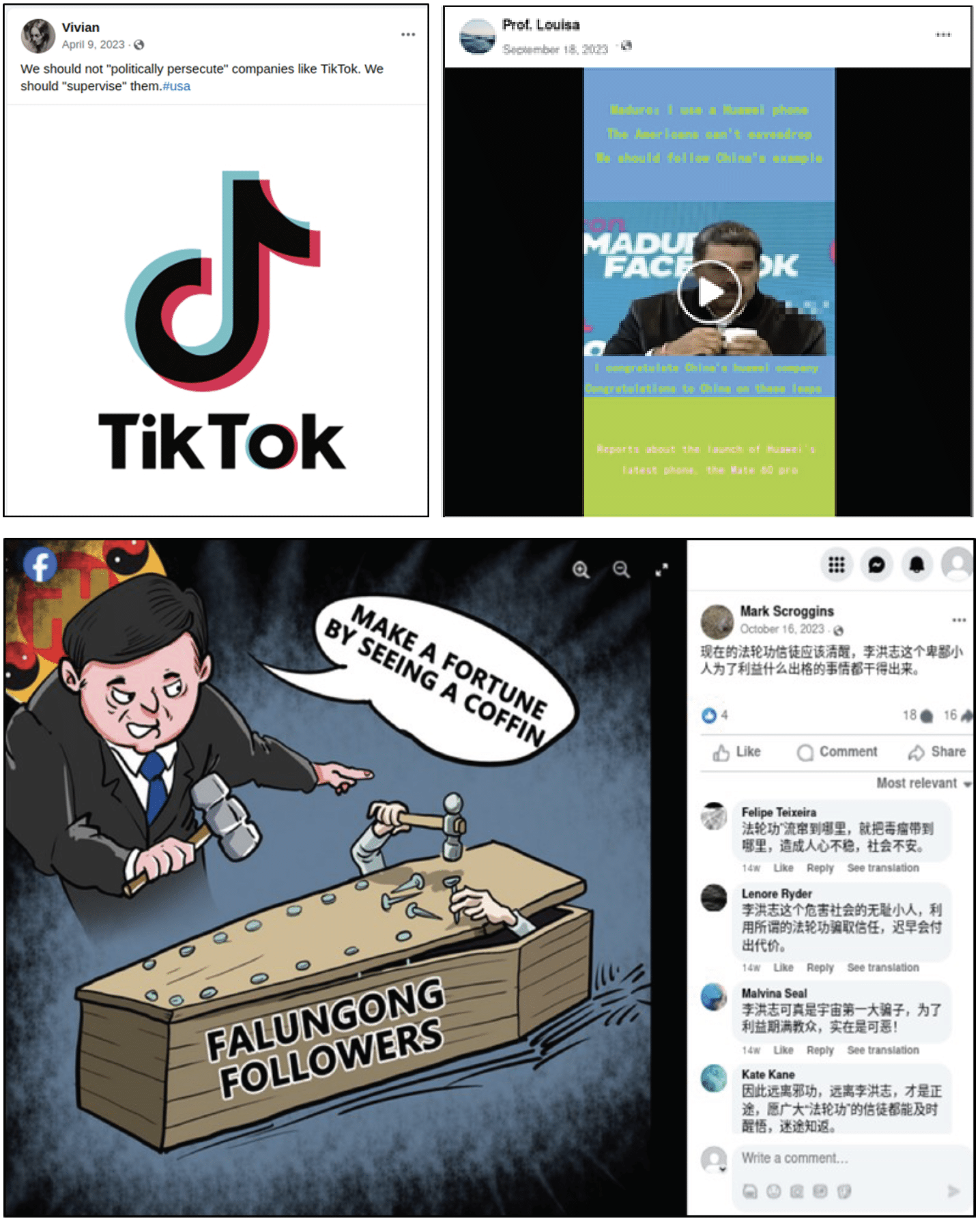

Consistent with previous Spamouflage behavior, the WoS network often criticizes Guo Wengui and the persecuted spiritual group Falun Gong.17 Even though Facebook is banned in China, this content criticizing Guo Wengui and Falun Gong is often in Mandarin, suggesting its target audience is Chinese speakers outside of China.18 The WoS network also promotes Huawei while condemning the alleged “political persecution” of TikTok (see Figures 1-3).19

Figures 1-3: Selected content from the WoS network criticizing U.S. scrutiny of TikTok, promoting Huawei phones, and criticizing Falun Gong

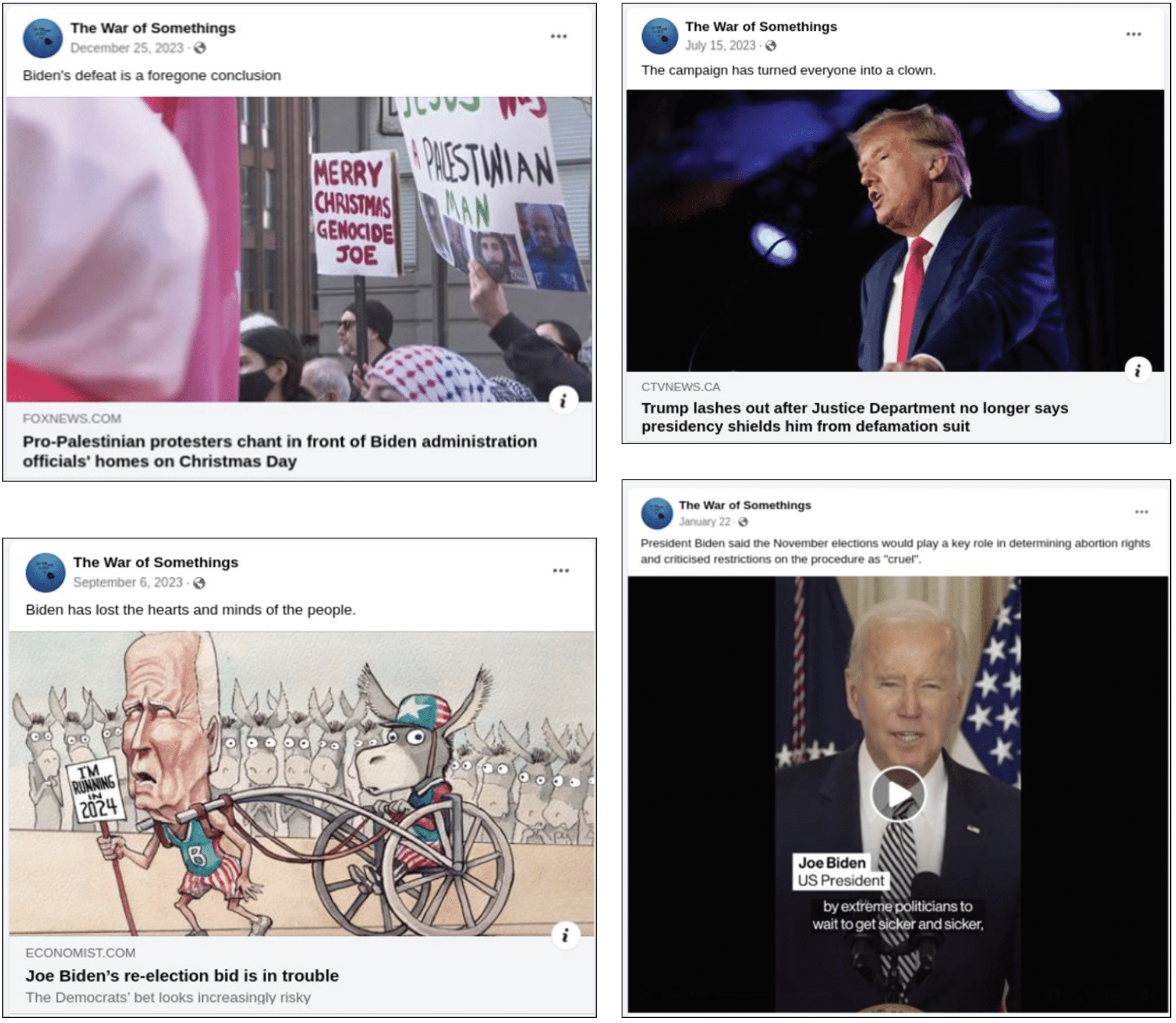

In 2022, the cybersecurity firm Mandiant observed Spamouflage criticizing the democratic process and attempting to dissuade Americans from voting in the midterm elections.20 With regard to the 2024 U.S. election, WoS members often assert that “The campaign has turned everyone into a clown,” yet “[Joe] Biden’s defeat is a foregone conclusion.” Attacks against Biden considerably outnumber attacks against former President Donald Trump. A British think-tank, the Institute of Strategic Dialogue (ISD) found a similar pattern in its report on Spamouflage’s U.S. election-related activity (see Figures 4-7).21

Figures 4-7: Selected content from “The War of Somethings” Facebook page explicitly referencing U.S. elections

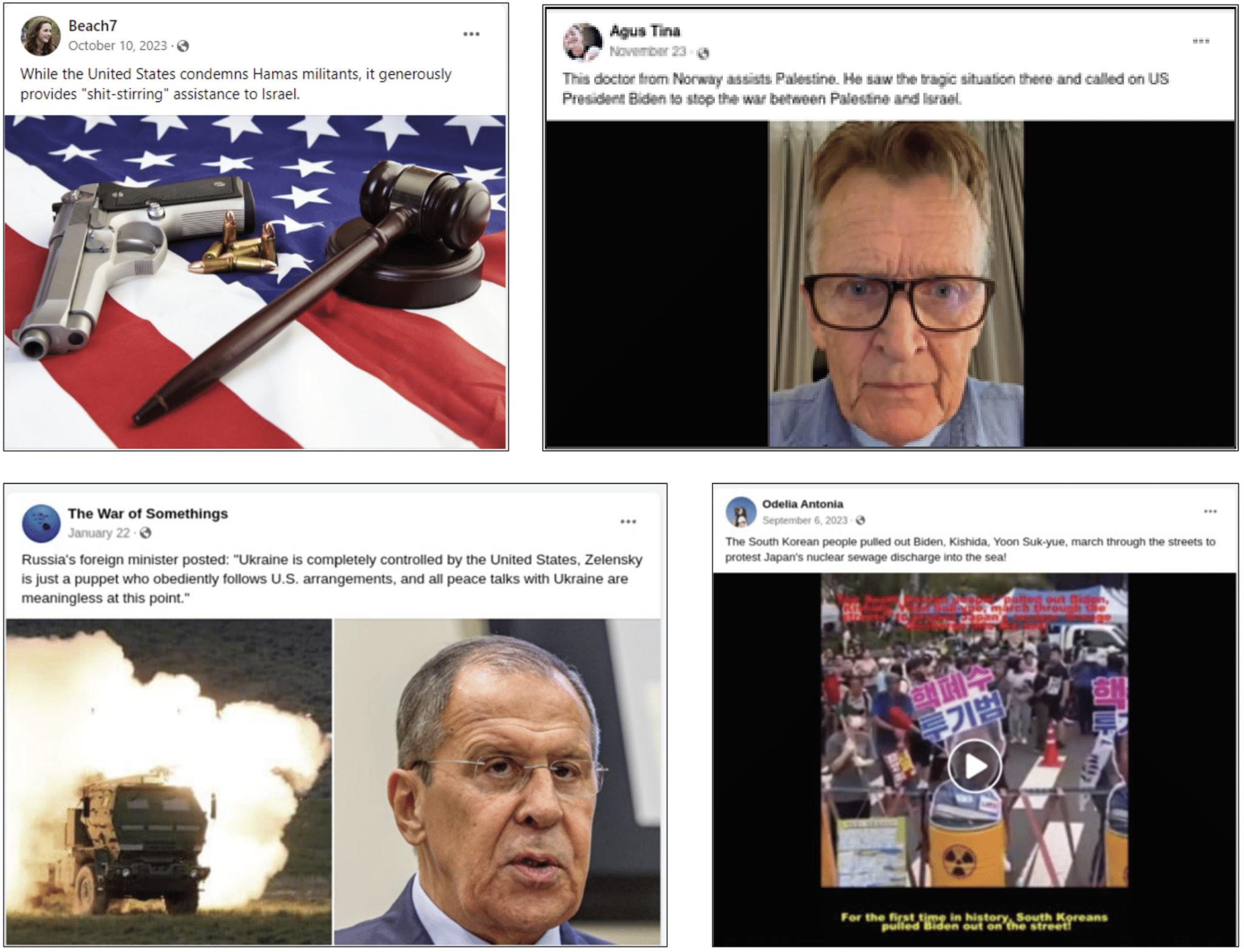

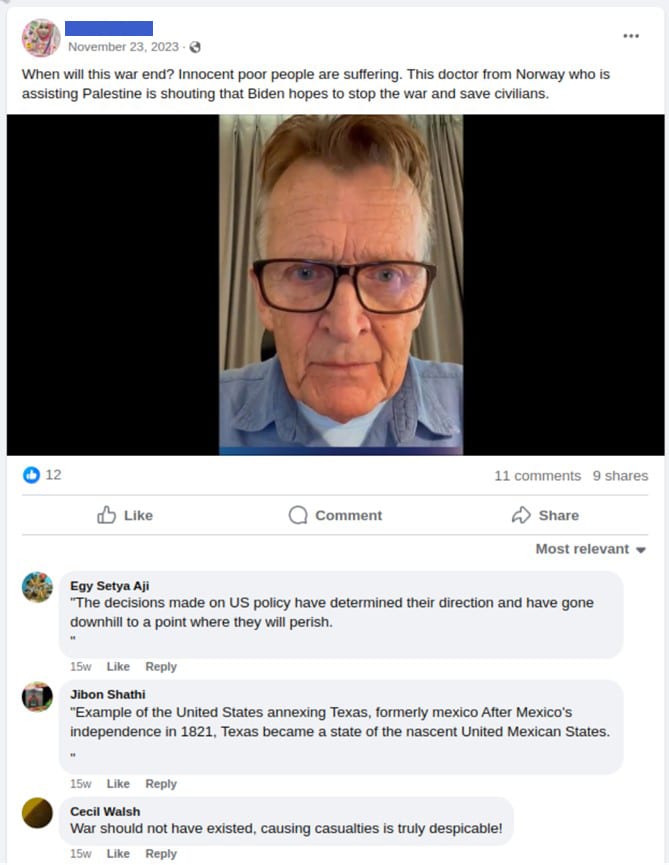

ISD has also documented how Spamouflage attempts to use the Israel-Hamas conflict to stir up anti-U.S. sentiment.22 Members of the WoS network claim the United States ignited the Israel-Hamas war, calling U.S. military assistance to Israel “shit-stirring.” The network amplifies calls from others to “stop the war.” Another target of criticism is U.S. support for Ukraine, which portrays Kyiv as an American “puppet.” The network also seeks to drive a wedge between South Korea and Japan, sowing discord among key U.S. allies with a shared interest in deterring Beijing (see Figures 8-11).23

Figures 8-11: Selected content from the WoS network criticizing U.S. support for Israel and Ukraine and highlighting South Korean protests against Japan

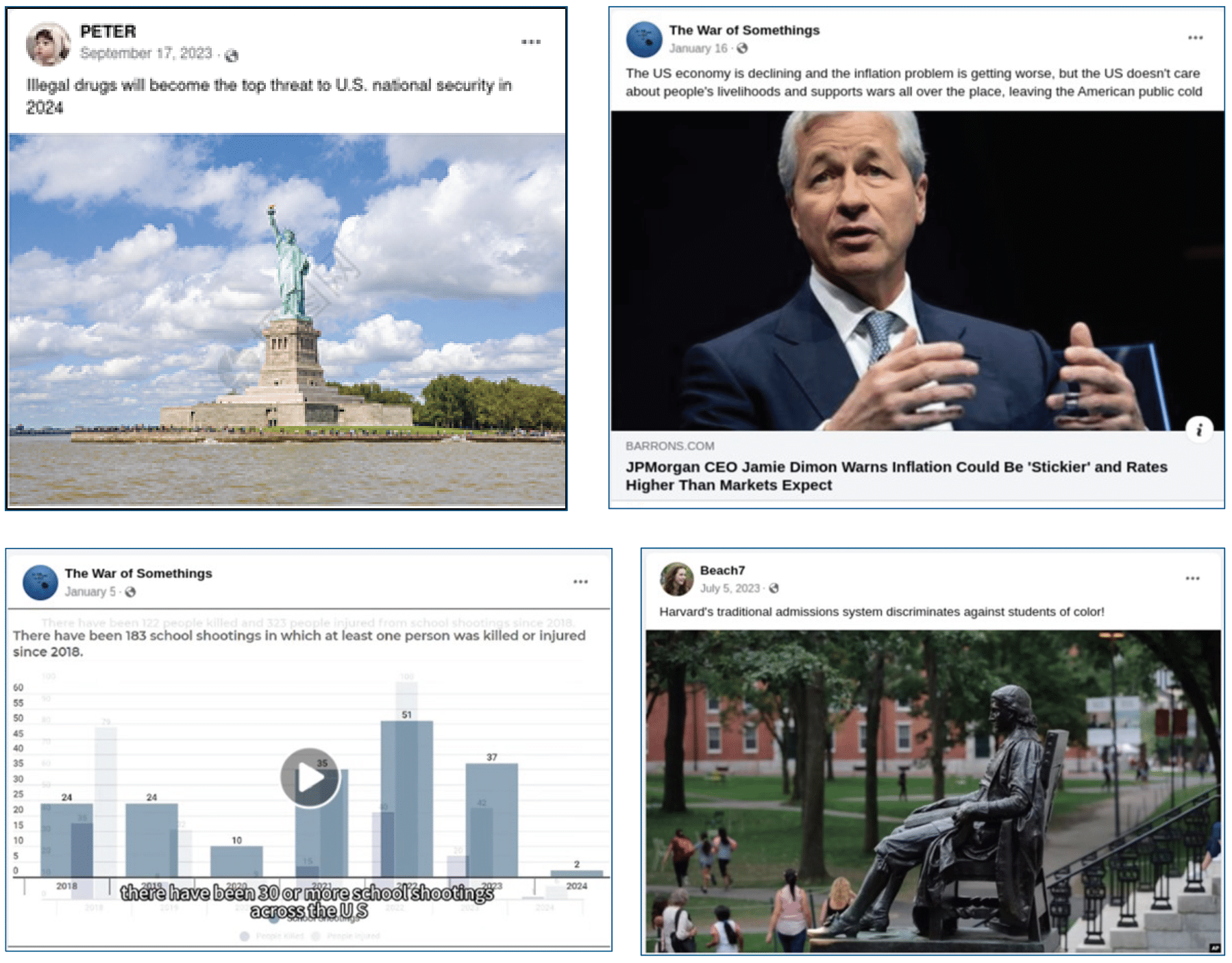

On the domestic front, the WoS network highlights drug deaths and gun violence, in a bid to show that the U.S. government prioritizes foreign policy over its people’s well-being. One comment opined, “In the current situation, the United States should consider the security of its own country and the safety of its people, but their actions have not only aroused dissatisfaction at home, but also had an impact on the international community.”24 This stilted language is typical of WoS content, indicating its operators lack English fluency.

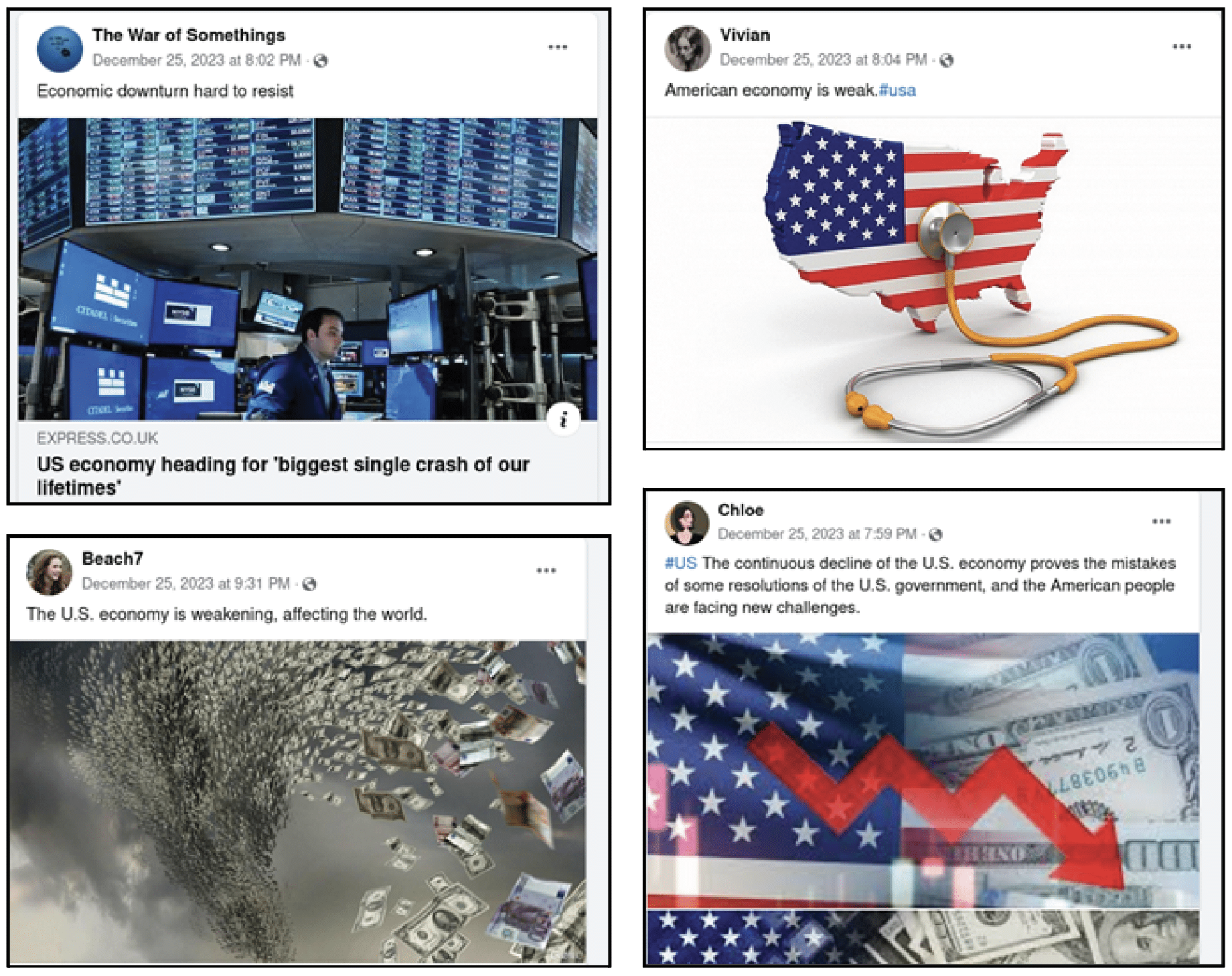

The network also points to alleged economic decline to assert that Washington neglects the American people in service of its aggressive foreign agenda. For example, “The War of Somethings” page wrote, “The U.S. economy is declining and the inflation problem is getting worse, but the U.S. doesn’t care about people’s livelihoods and supports wars all over the place leaving the American public cold.” Cultural wedge issues also receive substantial attention, including LGBTQ+ rights and race in college admissions.25 If an event casts U.S. leadership in a negative light, such as the U.S. response to the 2023 wildfires in Maui, it also becomes a focus (see Figures 12-15).26

Figures 12-15: Selected content from the WoS network commenting on issues ranging from drug deaths and school shootings to race in college admissions and the U.S. economy

Inauthentic Pages and Profiles with Coordinated Posting Habits

Despite the WoS network’s relative sophistication, there are tell-tale signs that it is an influence operation. Several user profile photos display signs of AI generation or do not match the profile’s listed gender. Like other components of Spamouflage, the WoS network sometimes intersperses apolitical content with its more agenda-driven material. Many members post nearly identical comments at almost the same time. The text includes markers of automatic translation while error messages included as profile photos indicate the automated pulling of stock images. The network is most active during working hours in China, even to the point of having an appropriately timed lunch break. There is no ‘smoking gun’ that confirms the WoS network is part of Spamouflage, but the distinctive behaviors point directly to that conclusion.

Inauthentic Profiles and Evidence of Automated Techniques

Many influence operations employ AI-generated profile pictures whose artificiality is sometimes visible to the naked eye. In the WoS network for example, ‘Priscilla Oreilly’ has glasses that blend into her head and then disappear. ‘Carmela Fay’ has an unidentified green object floating above her head.27 In another sign of inauthenticity, both profiles have inconsistent gender identities. ‘Priscilla Oreilly’ has a female name but a male profile image. ‘Carmela Fay’ has a female name and profile image but is listed as male (see Figures 16-17).28

Figures 16-17: A selection of AI-generated profile photos used in the WoS network

At least nine accounts in the WoS network use profile images from Getty Images’ stock photo service Unsplash.29 At least another six user accounts apparently tried but failed to automatically pull a profile picture using Unsplash’s application programming interface, a type of software that allows different applications to communicate with each other.30 These six profiles have an original profile photo displaying the error message “We couldn’t find the photo” with the URL of Unsplash, demonstrating the failure of an automated pull. These error messages show the haste and lack of care typical of Spamouflage operations. At the same time, the use of an application programming interface suggests the operators have a streamlined, automated process for generating accounts (see Figure 18).31

Figure 18: Example of an apparently failed attempt to retrieve a profile photo using the Unsplash API

While many profiles in the WoS network avoid such obvious signs of inauthenticity, other traits suggest many of the profiles were hijacked, either via direct theft of credentials or bulk purchase of credentials, which can be found on websites such as Telegram.32 Spamouflage appears to have used this technique in previous campaigns.33 In this instance, the suspect profiles were created years before posting their first political content. Before becoming part of the WoS network, they posted personal content and appear to have had genuine interactions with other accounts in their friend list. Furthermore, the friend list appears to consist of genuine people from the profile’s country of origin. While such accounts usually keep their original profile pictures, they no longer post personal content, only political content typical of the WoS network (see Figures 19-20).34

Figure 19: Profile photo from apparently authentic account that dates to 2017

Figure 20: The first post where the account began posting content common to the WoS network and received comments from accounts in the WoS network

Coordinated Posting, Machine Translation, and Photorealistic AI-Generated Fake Images

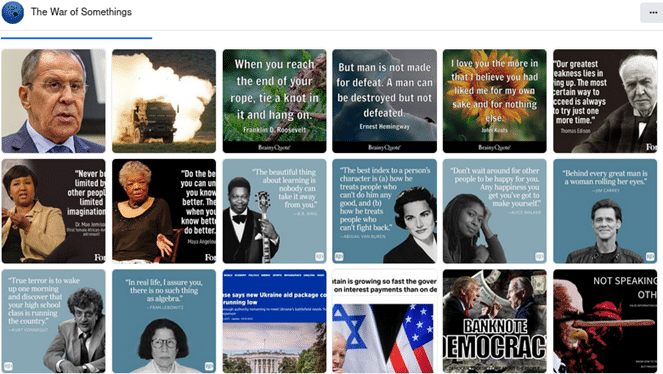

The posting habits of the WoS network also betray its inauthenticity. Graphika first observed the use of apolitical content to mask more contentious material in 2019 and named the influence operation “Spamouflage Dragon.”35 The “War of Somethings” page builds on this, interlacing uncontroversial quotes from famous writers, politicians, and cultural figures with its political content (see Figure 21).36

Figure 21: Screenshot of photos shared by “The War of Somethings” between September 16, 2023, and January 22, 2023, where apolitical content is shared in apparent attempts to camouflage the adversarial political nature of much of the page’s content

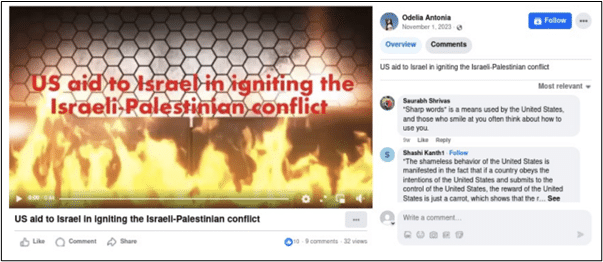

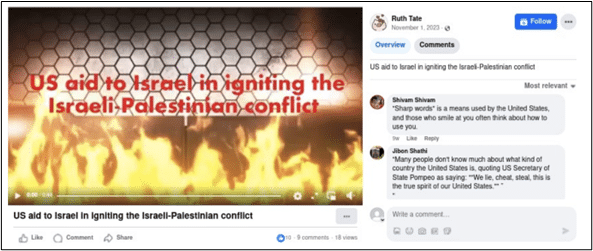

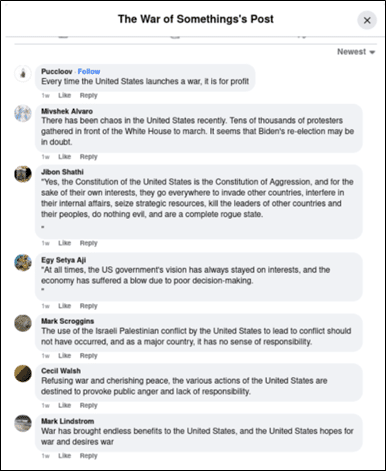

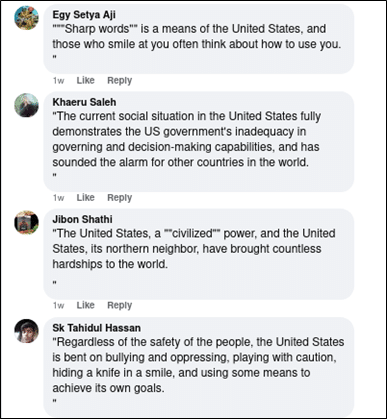

Tellingly, multiple pages and user profiles post identical or nearly identical content, sometimes as part of a single comment thread. The same user may also post identical or nearly identical comments on multiple threads. For example, ‘Ruth Tate,’ ‘Odelia Antonia,’ and “The War of the Somethings” page all posted the same video about Israel between 3:00 am and 3:26 am EST on November 1, 2023. The aforementioned ‘Lamonica Trout’ left the same comment — “America is the warmonger, the Jew’s own son!” — on all three posted videos. Beneath the video posted by “The War of Somethings,” ‘Sk Tahidul Hassan’ commented “‘Sharp words’ is a means used by the United States, and those who smile at you often think about how to use you.” Two other profiles, ‘Shivam Shivam’ and ‘Saurabh Shrivas,’ left the exact same comment on copies of the video posted by ‘Ruth Tate’ and ‘Odelia Antonia’ (see Figures 22-24).37

Figure 22: Video shared by “The War of Somethings,” the original lead for the WoS network

Figure 23: Identical video shared by the “Odelia Antonia” page, which is in the WoS network

Figure 24: Identical video shared by the “Ruth Tate” page, which is in the WoS network

This is a call-and-response pattern where one page or user profile establishes the theme, and then other pages and user profiles in the network reinforce and amplify the message. In a similar case, “The War of the Somethings” page shared a news article about a pro-Palestinian protest in Washington, DC, and wrote, “War brings nothing but harm to people, and it is the will of all mankind to stop it.” Other pages and user accounts in the network then left comments, such as “There has been chaos in the United States recently. Tens of thousands of protestors gathered in front of the White House to march. It seems that Biden’s re-election may be in doubt.” This call-and-response pattern is likely an attempt to give the appearance of actual engagement with the posts (see Figures 25-26).38

Figure 25: Post that serves first part of call and response by establishing theme

Figure 26: Comments on the above post from other accounts reinforce and develop this theme

The WoS network appears to use machine translation to generate English-language content, a behavior not previously associated with Spamouflage. Certain machine translation tools, such as ChatGPT, use quotation marks around translated text. Many comments left by the WoS network have quotes around the full text, almost always with the final quotation mark on a separate line below the final sentence. The dangling comma indicates hasty or automated posting. Its appearance in comments left by multiple user profiles confirms their association with each other (see Figure 27).39

Figure 27: Example of comments posted by accounts in the network that include quotation marks

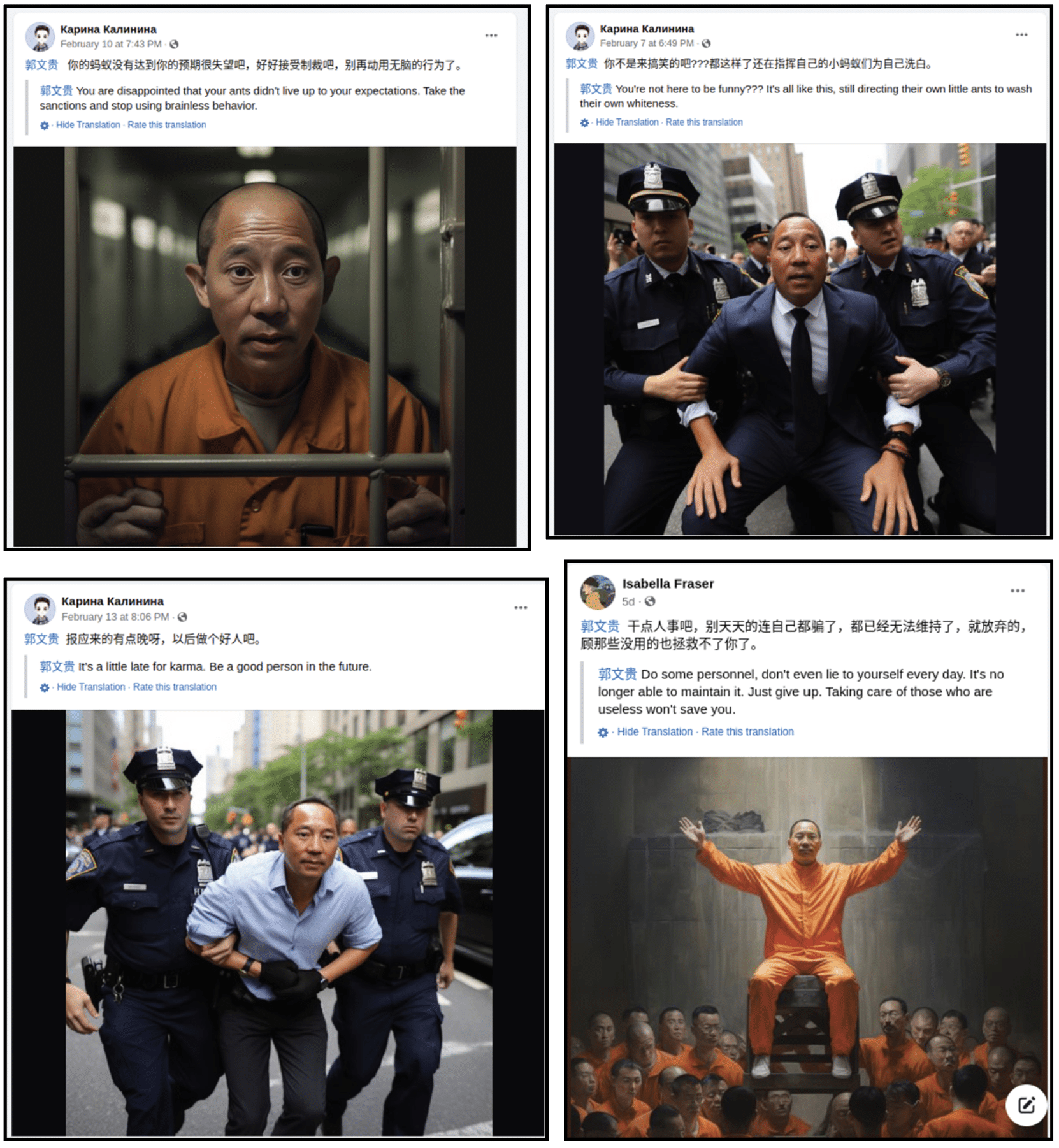

The WoS network also uses generative AI to create photorealistic fake images of Guo Wengui being dragged by police officers or locked in prison. For example, in the photo representing Guo Wengui behind bars, the hands are morphed and grotesque, while an unrealistic black silhouette outlines the figure’s head. In the photo of Guo Wengui wearing a suit while held by police, the irregular number of traffic lights, the warped text on the right police officer’s badge, and the warped hand by the right police officer’s shoulder all suggest that the photo was created with generative AI. Several other examples are provided (see Figures 28-31).40

Figures 28-31: Photorealistic fake images of Guo Wengui created with generative AI

Finally, there is one behavioral trait that could connect the WoS network directly to China: the network was mostly active between 7:50 pm and 5:00 am Eastern Time (GMT-5), with breaks between 11 pm and 12 am. The pages generally post content between 7:50 pm and 10 pm ET, and the user accounts generally comment between 10 pm and 5 am ET. This timing corresponds to 8:50 am to 6:00 pm in Beijing, with a lunch break between 12 pm and 1 pm (see Figures 32-35).41

Figures 32-35: Pages in the WoS network publish their content around the “weakening of the U.S. economy” between 7:59 pm and 9:31 pm Eastern Time on December 25, 2023

Recommendations: A Combination of Technology and Policy

While Meta took down thousands of accounts, pages, and groups associated with Spamouflage in August 2023,42 certain pages and user accounts have evaded detection, and new ones surfaced. The WoS network contains over 130 combined pages and profiles that predate the public release of Facebook’s August takedown. It also includes new assets, with the most recent being created on February 9. The WoS network has not had much impact so far, but Spamouflage has shown it can break out of its echo chamber to reach a sizable audience.

The following three measures would facilitate a more effective response by private companies and non-government organizations, helping them deny benefits to adversaries engaging in influence operations:

- Identify a ‘Technology Stack’ for Defending Against Influence Operations: Enhanced cooperation with independent researchers, analysts, and academics can help social media companies and security firms defuse influence operations. Yet to fully leverage the skills of these partners, social media companies and security firms should make sophisticated technological solutions available to them. To begin, companies and researchers should work together to identify an ideal technology stack for investigations into influence operations, akin to how cybersecurity defenders use a well-established suite of tools. Once these tools are identified, vendors should offer free or reduced-priced options to nonprofits and independent researchers who commit to using them to help counter-influence operations.

- Leverage Social Listening Tools: Social listening tools provide a panoramic view of social media and other media content such as online news and podcasts. While traditionally used by marketing and public relations teams to understand social trends and brand reputation, these tools can bring powerful capabilities to investigations into influence operations. For example, Graphika has used the social listening tool Meltwater to quickly discover accounts that retweet content from Spamouflage accounts. More research and testing are needed to understand the full capabilities that companies like Meltwater, Brandwatch, Talkwalker, and others might bring to investigations into foreign influence operations. These companies can better understand their tools’ full potential by giving independent researchers increased access to these tools.

- Improve Partnerships and Interaction Processes Between Social Media Platforms and Researchers: Social media platforms should acquire or create tools that will not just enhance the platform’s capabilities but also help empower independent researchers. Facebook’s 2016 purchase of the social media monitoring tool Crowdtangle and its decision to make it available for free to researchers illustrate the potential for synergy. This benefited Facebook because Crowdtangle helped the community of independent researchers identify influence operations that evaded Facebook’s internal team. Platforms should also make the process of reporting influence operations more streamlined and less opaque. Social media platforms should create and communicate a defined process for reporting influence operations, designating and publicly sharing specific points of contact for this activity. Companies can also further streamline the process by defining reporting formats and requirements.

While social media companies can take down hostile foreign influence operations, there is little they can do to dissuade foreign governments from launching these operations in the first place. Here, the federal government can play a unique role by directly applying pressure to adversaries that launch influence operations. In particular, it should:

- Strengthen Declaratory Policy on Hostile Foreign Influence Campaigns: When the congressionally mandated Cyberspace Solarium Commission issued its March 2020 report, one of its first recommendations to the U.S. government was to issue a new declaratory policy on cyberspace. The commission noted, “When buttressed with clear and consistent action, a declaratory policy is essential for deterrence because it can credibly convey resolve.”43 Similarly, the White House should communicate to the American people, its allies, and its adversaries abroad that the U.S. government will impose costs — diplomatic, financial, or otherwise — on threat actors engaged in hostile influence operations targeting the United States. The policy should emphasize that influence operations that attempt to interfere with U.S. elections or incite civil unrest and violence will provoke a harsh response.