September 14, 2023 | Memo

Capital Markets with Chinese Characteristics

Xi’s Declaration of Lawfare

September 14, 2023 | Memo

Capital Markets with Chinese Characteristics

Xi’s Declaration of Lawfare

Beijing is re-engineering conditions for foreign businesses with a raft of new laws and regulations that seek to bend investors to the ruling party’s priorities and render overseas regulators irrelevant.

The new legislation likens many normal business practices to espionage. In capital markets, Chinese regulators have instructed lawyers writing prospectuses for overseas initial public offerings (IPOs) to water down language on business risk in China. And a new concept for pricing IPOs — “valuation with Chinese characteristics” — aims to privilege firms that align with Beijing’s political priorities.

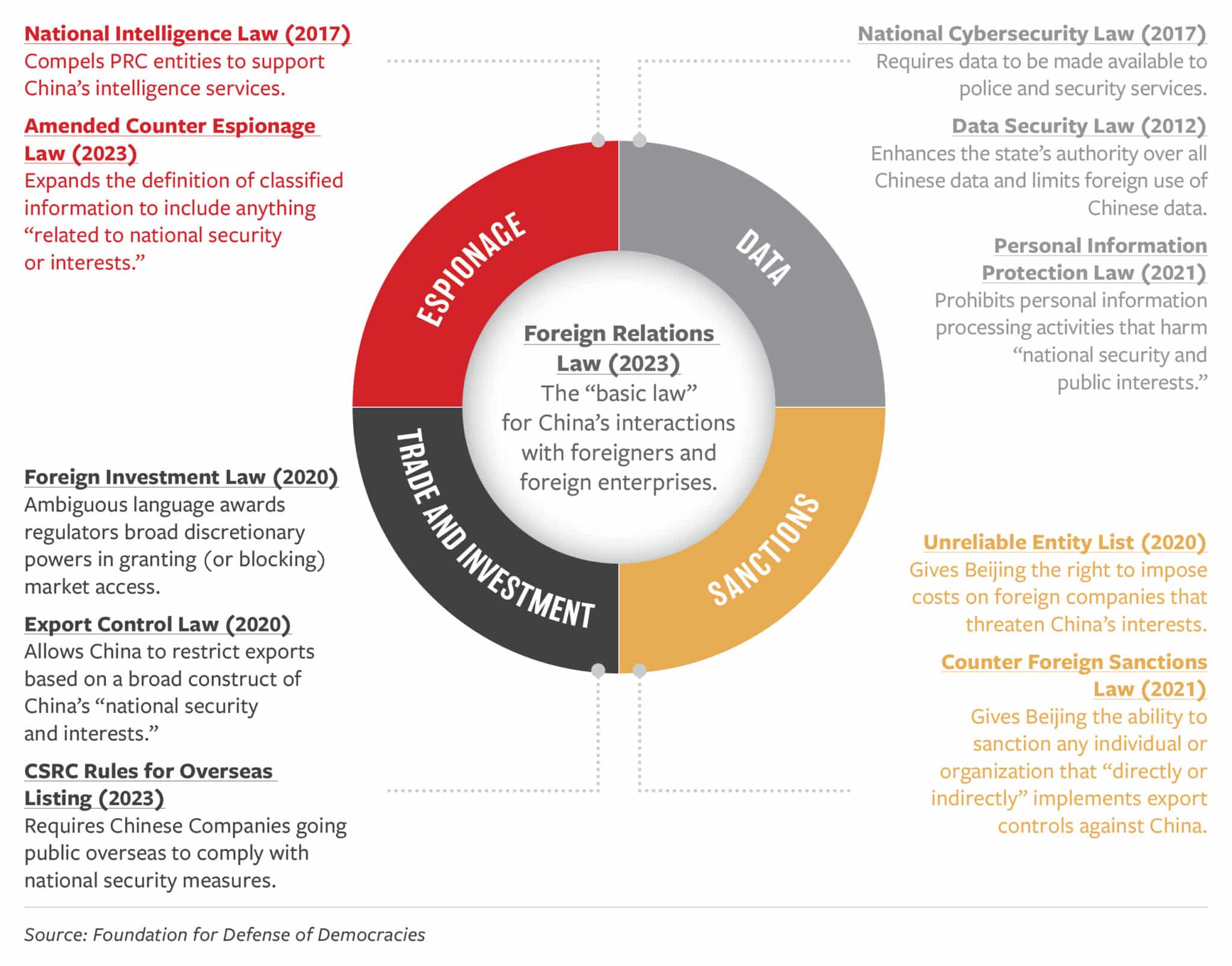

Taken as a whole — and further informed by an essay by top diplomat Wang Yi — China is executing an integrated program of “lawfare” to control information flows and to force businesses to choose between Chinese and Western legal and regulatory systems that are increasingly incompatible.

Not Your Everyday Public Service Announcement

On July 31, the Ministry of State Security (MSS) launched a public WeChat account with a directive for Chinese citizens to aid in the counter-espionage fight. The MSS declaration was not your everyday public service announcement. It required “broad participation of the people” and promised rewards to those who help China win what it describes as a “grim and complex” battle against foreign spies.1

Since then, posts by local public security offices on Douyin (ByteDance’s Chinese version of TikTok) have offered a 500,000 RMB award for catching foreign spies.2 State media, meanwhile, have reported extensively on the arrest of a Chinese military-industry technician accused of spying for the CIA.3

The MSS circular was prompted by Beijing’s expansion of its Counter-Espionage Law. The revised law, which took effect on July 1, widens the definition of “espionage” to encompass ordinary international business practices such as gathering information on local markets, potential business partners, and competitors. It adds to what is now a formidable array of laws, regulations, and administrative agencies that enable China’s leaders to shape the information environment, harness data as a national resource, guide the allocation of capital, and expand Chinese Communist Party (CCP) control over China’s economic relations with the outside world.

Beijing’s latest efforts to stanch the flow of market information are starting to bite. The Financial Times reported last month that PRC authorities have warned local brokerage analysts and researchers at leading universities and state-run think tanks to stop speaking negatively about China’s sclerotic economy.4

Meanwhile, new disclosure rules for IPOs, a data-related crackdown in the food and beverage sector, and a corruption-related “rectification” campaign in the pharmaceutical industry are all adding pressure on foreign enterprises to align with the priorities of the CCP.5

In response to Beijing’s legal campaigns, foreign professional services firms are taking defensive actions to mitigate risk. Faced with looming measures to restrict cross-border data sharing, financial firms have been erecting stand-alone systems of client data in China. Goldman Sachs and UBS now run separate systems for their China operations. On July 18, Bloomberg reported that Morgan Stanley had moved 200 tech developers out of mainland China as it built a stand-alone data system for PRC clients.6 On August 8, Dentons, one of the world’s biggest law firms, announced it was hiving off its operations in China in response to intensifying regulations, including new requirements “relating to data privacy, cyber security, capital control and governance.”7

These examples highlight a growing incompatibility between global capital markets, premised on open information flows and anchored in the rule of law, and Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s conception of a market system that must serve the interests and objectives of the “real economy,” as defined by the Party.

The recent moves to subordinate foreign investment banks, law firms, consultancies, data providers, and, in effect, regulators such as the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) represent a new phase in the creation of capital markets with “Chinese characteristics.”

Xi remains undaunted in his effort to subject all market players to Party discipline — an agenda he announced in July 2021 with the launch of a multi-year campaign to eliminate “illegality” from markets. This agenda’s most recent manifestations include raids, arrests, and legal changes that have accompanied the “rectification” of the consulting and due-diligence sector so central to foreign investment in China.8

This disciplinary and counter-espionage campaign creates an information vacuum that Xi now seeks to fill with a positive and heavily redacted view of market conditions more aligned with Party goals of restoring confidence in China’s future growth prospects.

This “airbrushing” of the Chinese economy relies on a complex toolkit of new IPO regulations, politically directed investment marketing, informal messaging, and, ultimately, coercive lawfare. As this process intensifies, foreign firms will find it increasingly difficult to protect independent data, research, and freedom of investment decision-making even when these activities do not explicitly clash with the Party line.

How this new disciplinary phase will affect investors and multinational corporations remains to be seen. Indications so far suggest that pressure to demonstrate support for Beijing’s economic agenda is reaching a tipping point — meaning that the risk of reprisal for failure to heed these demands is rising.

Diluted Disclosures

The Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKSE) has long required companies in mainland China to publicly address China-related risks when they list their stocks. The rules required issuers to identify material risks deriving from China’s distinctive political, business, and regulatory environment, including “the political structure and economic environment” and “foreign exchange controls.” But on August 1, the HKSE repealed the requirement for this special China-risk section from its listing application rules.9

The removal of this section flowed from a HKSE “consultation conclusions paper” released on July 21. This paper, in turn, was published a day after the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) met with China’s official lawyers’ association and reportedly directed its members to water down language describing China-related business risks in Chinese companies’ offshore listing documents and other communications.10

According to a subsequently censored post on the Chinese social media platform Weibo, CSRC officials said the moves reflected feedback from central leadership officials who said the prospectuses for foreign IPOs contained sections that “discredited” China and were “seriously untrue.”11

Of concern, the post stated, were descriptions in the prospectuses and other corporate documents mentioning uncertainties and problems in China relating to the PRC legal system, the enforcement of foreign court judgments, the implementation of arbitration agreements, government controls distorting the allocation of capital and resources, the sustainability of economic growth, and government interference in business operations.

CSRC officials reportedly warned the lawyers that they must “strictly implement” the New Overseas Listing Regulations issued in February. They cited Article 12, in particular, which bans negative information about China:

Securities companies, securities service agencies and personnel engaged in overseas issuance and listing of domestic enterprises … shall not express opinions in documents that distort or derogate national legal policies, the business environment, the judiciary, etc.12

The CSRC’s interpretation of Article 12 — and the HKSE’s implementation of that interpretation — means that bankers and lawyers involved in raising capital in China (including in Hong Kong) are being forced to choose between Chinese and Western legal and regulatory systems that are increasingly incompatible.

By acceding to these new requirements, lawyers in both Hong Kong and mainland China risk contravening the requirements of U.S. securities law for full disclosure of meaningful liabilities.

They may also be in danger of violating the agreement worked out between U.S. regulators and their Chinese counterparts in August 2022 to avoid the threatened de-listing of Chinese companies from U.S. stock exchanges. To underscore this point, the SEC sent a letter this summer reminding PRC firms listed in the United States that, under last year’s agreement, the firms are required to address several risk factors clearly in submissions to the SEC. The SEC letter states that PRC firms listed on U.S. exchanges “should provide more prominent, specific, and tailored disclosures about China-specific matters so that investors have the material information they need to make informed investment and voting decisions.”

The letter listed the following specific risk factors:

- “the percentage of shares owned by foreign government entities”

- “identification of all Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials who are on the board of the issuer or the operating entity for the issuer”

- “any material impacts that intervention or control by the PRC in the operations of these companies has or may have on their business or the value of their securities”

- “disclosures related to material impacts of certain statutes,” including “the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act… These impacts may include material compliance risks or material supply chain disruptions that companies may face if conducting operations in, or relying on counterparties conducting operations in, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.13

In other words, the positions of the PRC and U.S. securities regulators are now diametrically opposed. Lawyers, bankers, and their fundraising clients can observe PRC disclosure requirements or U.S. disclosure requirements, but they can no longer do both.

Creative Valuations

In November 2022, CSRC Chairman Yi Huiman coined the term “valuation with Chinese characteristics,” as he argued that the market needed a new way to price state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to encourage foreign investment in sectors that would benefit the Party.14

Since then, brokerages have promoted the stocks of SOEs, which still play a pivotal role in China’s economy, especially in public infrastructure, energy, and telecommunications. The stock prices of several of those companies — including China Telecom, China Mobile, and PetroChina — have gained more than 50 percent this year.

It is increasingly clear that Beijing’s new valuation concept is designed to attract capital into SOEs and sectors favored by Xi.

In May 2023, Yang Chengchang, a leading economist who has advised China’s State Council, explained in the state-run Shanghai Securities News that “valuation with Chinese characteristics” means that “industries and enterprises that are closely integrated with Chinese-style modernization may receive a valuation premium.”15

Yang foresaw a day when firms that align themselves with Party priorities in Xi’s “new economy” — such as “information technology, AI, biotech, new energy and materials, green tech, high-end equipment and EVs” — could all receive positive valuations not because of profit expectations but because they supported the Party’s policies.

In relation to national security-related firms, he wrote, “for companies with outstanding market positions in the fields of national defense security, data security, and financial security, they will gain improved valuation due to their security contributions.” This is how Beijing directs capital markets to adhere to China’s defense needs.

United Front Meets Venture Capital

On July 9, Premier Li Qiang signed an order of the State Council to announce new regulations concerning private equity and venture capital. China’s state-run Xinhua News Agency highlighted two key points that stress the Party’s role in guiding private equity and venture capital to comport with Party priorities:

- “The State provides policy support to venture capital funds to encourage and guide them to invest in growing and innovative start-ups, strengthen the coordination and cooperation between supervision and management policies and development policies, and clarify the conditions that venture capital funds should meet.”

- “It is stipulated that the supervision and management of private investment fund business activities shall implement the Party and state’s guidelines, policies, decision-making and deployment.”16

A month earlier, on June 9, a National Alliance of Venture Capital Associations had been “formed spontaneously and voluntarily” for the purpose of steering venture investments and know-how into areas prioritized by the Party.17 This new organization was initiated by the Securities Times, a major state-run media outlet. A representative of the Securities Times was named one of the alliance’s two permanent chairmen.

At the inaugural meeting of the alliance, Ji Xiaolei, Party secretary of the Securities Times, said his newspaper was happy to act as a “bridge” to unite venture capital firms from around China. Given that venture capital and other private-equity money play a major role in China’s financial markets, he said, the Securities Times was eager to “build a platform to provide assistance and make contributions to the high-quality development of the venture capital industry.”18

With the Party’s direct involvement, the new venture capital association has all the trappings of a United Front organization aimed at deepening Party influence over the industry.

The Foreign Relations Law

On July 1, the same day that the amended Counter-Espionage Law took effect, another important law came into force: the Law on Foreign Relations. Chinese authorities point to it as providing the guiding framework for Beijing’s use of legal “weapons” to push back against alleged U.S.-led containment and reshape the international order in China’s favor.

With the law’s passage, foreign investors, corporations, and policymakers should brace for a more coordinated and frontal deployment of law and regulations in support of the Party’s interests.

The underlying aims of China’s legislative moves are often explained in authoritative side notes. In this case, an explanation of the Foreign Relations Law was authored by China’s top diplomat, Wang Yi, who was recently re-appointed as foreign minister after the still-unexplained disappearance of his predecessor, Qin Gang.19

Wang’s essay, published in the People’s Daily on June 29, articulates Beijing’s legal strategy against hostile foreign interests and provides a key theoretical basis for understanding the recent legislative moves to block the flow of market information and push foreign businesses to support Party policy. Wang described China’s rule-by-law system as a “weapon” and positions the Foreign Relations Law to be the “Basic Law” to frame and guide Beijing’s legal “struggles” against foreign adversaries. As Wang wrote:

In the face of severe challenges, we must maintain strategic determination, advance despite difficulties, confront difficulties, dare to struggle, be good at struggling, including making good use of rule-by-law as a weapon, constantly enriching and improving the legal “toolbox” for foreign struggles, and giving full play to the positive role of law as a “stabilizer” of the international order.

Wang positions the Foreign Relations Law as providing crucial legal tools to oppose businesses and individuals perceived as supporting the exercise of U.S.-led power against Chinese interests, including the trade tariffs imposed by the Trump administration; Western restrictions on selling advanced technologies to China; sanctions on Chinese officials for human rights abuses; and criticism of China’s actions in and around the South China Sea, Taiwan, Xinjiang, and Hong Kong and against Chinese dissidents. According to Wang:

The formulation of the Foreign Relations Law clearly opposes all hegemonism and power politics, opposes any unilateralism, protectionism, and bullying behaviour, and clearly counteracts restrictive legal provisions of foreign interference, sanctions, and sabotage against our country. It is conducive to playing the role of prevention, warning and deterrence, providing a legal basis for our country to exercise the legitimate rights of anti-sanctions and anti-interference in accordance with the law.

Wang tied the law’s codification of legal warfare to Xi’s comments at the 20th Party Congress last October, when Xi declared that China’s strategic operating environment had deteriorated:

The world has entered a new period of turbulence and change. We must strengthen our sense of worry, adhere to bottom-line thinking [i.e. Party security], prepare for danger in times of peace . . . and prepare to undergo high winds and waves, and even for the stormy seas of a major test.20

Wang wrote that the Foreign Relations Law was motivated by the need to “accelerate the formation of a systematic and complete system of foreign-related laws and regulations.”

And he signalled Beijing’s intent to strengthen, coordinate, and create more legislative “weapons.” China must “[a]ccelerate the research and formulation of supporting laws, regulations and documents, and ensure that various systems are implemented as soon as possible,” said Wang.

Conclusion

The political compliance burden is rising in China, as are the costs of non-compliance. This is a direct challenge to U.S. regulations and regulators of capital markets. Whether these moves will render the SEC increasingly irrelevant remains to be seen. Asset managers with a fiduciary duty to their clients and investors must pay close attention to the curtain of legally mandated opacity rapidly decending on the Chinese economy and business environment — even if the federal government is not.

China’s “Legal Toolbox for Foreign Struggles”

“Make good use of rule-by-law as a weapon and constantly enrich and improve the legal ‘toolbox‘ for foreign struggles.” – Wang Yi, June 29, 2023