October 28, 2022 | CEEW Monograph

China’s Accelerating CEEW Campaign

October 28, 2022 | CEEW Monograph

China’s Accelerating CEEW Campaign

Introduction1

In the four years since the Foundation for Defense of Democracies published its first study on Chinese CEEW,2 the United States and the People’s Republic of China have remained locked in a long-term struggle for political, military, and economic dominance. As the United States endeavors to lead and preserve the international order, Beijing seeks to alter global dynamics to promote its interests while diminishing the influence of the United States and other free-market democracies.3 Accordingly, China’s use of CEEW has increased in scope, scale, and frequency.

Beijing’s approach to CEEW combines IP theft, economic coercion, critical-infrastructure disruption, and the large-scale collection of personally identifiable information of U.S. citizens. For the United States and allied countries to deter and confront Chinese CEEW, they must understand how Beijing views this toolset. This chapter therefore begins by delving into the Chinese military doctrine that undergirds Beijing’s approach to CEEW.

While other adversaries simply seek to weaken the United States and its allies, China also seeks to control the infrastructure of the global economy. Beijing’s plan to dominate the global ICT domain is one of the clearest examples of CEEW in action. To that end, China is planting its equipment throughout the global infrastructure and then leveraging that equipment to gather, manipulate, or otherwise control the vast amounts of data moving through the system.4

Yet Beijing is not just looking to control data flows. Beijing is also pursuing self-reliance and eventual dominance over ICT. To mitigate its susceptibility to U.S. influence, China wants to become leader in the development of new technology instead of just an importer of technology and manufacturer of final goods.5 To that end, Beijing combines state-directed support for national champions and barriers against foreign firms operating within its borders with illicit and hostile CEEW activities such as IP theft, cyber manipulation, and economic coercion. Altogether, China has implemented a coherent long-term strategy to control key nodes in the global economy and communications infrastructure — all at the expense of the United States and its allies.

Chinese CEEW, Political Warfare, and ‘Winning Without Fighting’

CEEW is an American concept that aligns with the Chinese approach to strategic competition. In that context, CEEW is effectively a subset of Beijing’s long-standing approach to political warfare (政治战), as encapsulated by the “Three Warfares” (三战) doctrine first enunciated by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in 2003. These three techniques — public opinion warfare (舆论战), psychological warfare (心理战), and legal warfare (法律战)6 — are intended to shape domestic and foreign attitudes and perceptions in ways that advance China’s interests and constrain the political and military options of China’s opponents during times of peace, crisis, and conflict.7 For Chinese analysts, a principal advantage of CEEW and other forms of political warfare is their potential to exploit American vulnerabilities while avoiding escalation to war.

In Chinese texts, political warfare goes beyond media or propaganda operations to include all direct and indirect means of manipulation. While Chinese political-warfare literature does not directly address in depth the fusion of cyber and economic tools, Chinese analysts consider these tools, used alone or together, to be powerful means of influencing public opinion, altering an adversary’s political environment, and diminishing its resolve in a crisis.8 More importantly, CEEW techniques reduce the risk of a conventional military confrontation — a domain where China feels, at least for now, unprepared to challenge the United States and its allies.

China’s long-established concept of “winning without fighting” (不战而胜) favors indirect or unconventional methods to achieve strategic objectives while avoiding unnecessary escalation or crises.9 Chinese strategists argue that the globalization of economics and information flows has “significantly increased the restriction of warfare,” channeling countries toward smaller conflicts or non-military confrontations, to which Chinese political warfare is uniquely suited.10 For example, cyberattacks can exert “a direct and powerful influence” on an adversary’s economic system, precipitating social, economic, or political collapse.11

While Chinese scholars believe the United States is adept at deploying unconventional or “hybrid” warfare, they also recognize that America and its allies face considerable difficulty when it is used against them.12 These scholars cite the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea as a notable example.13 Another theme in Chinese views of the United States is that America’s prevailing strengths can, with the right tools, become vulnerabilities that Beijing can exploit via asymmetric cyber operations and cyber-enabled economic coercion.

Chinese strategists see the U.S. political system and private sector as principal areas of vulnerability. Many Chinese scholars have asserted that economic disruptions would be particularly effective in undermining America’s political resolve during a crisis, since the party out of power would blame the incumbent administration amidst mounting economic losses.14 Beijing also believes it can leverage U.S. industry to advance China’s objectives — or at least temper U.S. actions that would harm Chinese interests. Vice Foreign Minister Xie Feng, for example, urged U.S. businesses to push the U.S. government to pursue more CCP-friendly policies, warning that businesses cannot expect to “make a fortune in silence.”15

Chinese authors also view cyber and economic tools as useful means to test the reliability of U.S. security guarantees. PLA military theorists discuss the concept of a “divide, break, and exploit” (分化瓦解, 酌情利用) economic policy that seeks to create division and discord among U.S.-led coalitions.16 In this scenario, China would utilize CEEW techniques, coupled with traditional economic coercion that falls below the threshold of armed conflict, to show that America’s allies cannot rely on U.S. protection. Absent a threat of physical harm to U.S. citizens or military personnel, the thinking goes, American politicians, voters, and corporate leaders would see little benefit in defending a foreign country against economic coercion.

CEEW Techniques

IP Theft

Cyber-enabled IP theft is the most well-recognized and longstanding CEEW tactic employed by the CCP. Beijing “continues to use cyber espionage to support its strategic development goals—science and technology advancement, military modernization, and economic policy objectives,” the U.S. intelligence community reported in 2018.17 A U.S. government assessment in June 2021 confirmed that China is “aggressively” targeting U.S. and allied technology, both commercial and military.18

Despite a dip in Chinese IP theft following the 2015 summit between President Barack Obama and Chinese leader Xi Jinping, cybersecurity researchers and the U.S. government have seen a resurgence of Chinese cyber intrusions beginning in 2017 and continuing today.19 In the fall of 2021, U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai stated that the Biden administration was prepared to “build on” existing tariffs against China first imposed under the Trump administration in response to China’s IP theft and unfair practices related to technology transfer.20 She said the phase one agreement between the United States and China meant to alleviate these issues has “not meaningfully address[ed] the fundamental concerns that we have with China’s trade practices.”21 Six months later, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative’s annual IP report continued to rank China among the most egregious violators.22

The People’s Republic of China strives to weaken IP protection via Chinese courts. Specifically, Beijing is using “anti-suit injunctions” to block foreign companies from taking legal action to protect trade secrets. In one case, Xiaomi, a large Chinese consumer electronics and smartphone producer, secured an injunction barring Delaware-based InterDigital from pursuing a patent infringement case against Xiaomi, not only in China but worldwide. A Chinese court ruled that if InterDigital continued to press its legal rights, the company would be fined nearly $1 million per week.23

Critical-Infrastructure Intrusions

Cyber-enabled critical-infrastructure disruption is a focal point of Chinese military literature. Military theorist Ye Zheng argues that cyber operations against critical infrastructure can generate “space and time on the battlefield,” delaying and confounding an adversary’s response until Chinese forces can establish a new status quo for concessions and negotiation.24 While focused on targeted disruptions of critical infrastructure that supports adversary military capabilities, Chinese strategists acknowledge that such disruptions may “sow fear and panic amongst the enemy,” “compel adversaries away from rash activities,” and “paralyze a nation’s economy and sow societal disorder, allowing one country to impose its will upon the other.”25

China’s conception of military conflict in cyberspace blurs the distinction between peace and war. As Zheng notes, “the strategic game in cyberspace is not limited by time and space, does not distinguish between peace and war, and has no frontline and homefront.”26 In CEEW, the ability to coerce an adversary through critical-infrastructure disruption in wartime is contingent upon cyber intrusions conducted in peacetime.

Despite this emphasis in the literature, the PLA has been relatively slow to operationalize critical-infrastructure disruption in its cyber operations — at least compared to other sophisticated adversaries, such as Russia.27 The Biden administration revealed last year that between 2011 and 2013, China compromised nearly two dozen U.S. oil and natural gas pipelines, potentially to disrupt or damage their operation.28 In 2014, then-NSA Director Mike Rogers stated that China, along with Russia, was capable of mounting cyberattacks against the U.S. electric grid.29

Since then, China’s investment in such operations has accelerated sharply, and critical-infrastructure intrusions by Chinese cyber actors have increased. In 2019, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence reported publicly for the first time that Chinese cyber actors could “launch cyberattacks that cause localized, temporary disruptive effects on critical infrastructure,” and singled out oil and natural gas pipelines as a sector that could be disrupted for days or even weeks.30 The U.S. intelligence community reaffirmed this in 2021.31

Cyberattacks on critical infrastructure could disrupt a U.S. military mobilization in defense of Taiwan or interfere with other military operations by China’s adversaries.32 In mid-2020, amid border skirmishes with India, suspected Chinese actors targeted Indian critical-infrastructure sites, including “a dozen critical nodes across the Indian power generation and transmission infrastructure” as well as two Indian seaports.33 These intrusions may have caused power outages in Mumbai in October 2020, which effectively halted economic activity within one of India’s major economic centers,34 although the linkage remains unconfirmed.

Cyber-Enabled Economic Coercion

FDD’s 2018 report on Chinese CEEW detailed Beijing’s use of cyber-enabled economic coercion, drawing attention to attacks on the South Korean conglomerate Lotte Group after the company agreed to let Seoul use a Lotte-owned golf course for U.S. missile defense deployments.35 Chinese actors continue to use this tactic, which seeks to compel action rather than cause disruption or chaos. Weeks after Nairobi rejected a free trade agreement between the East African Community countries and Beijing in May 2018, for example, Chinese actors began aggressively conducting cyber intrusions against Kenya.36 There is no indication, however, that this tactic succeeded in changing Kenya’s policies.37

It can be difficult to distinguish cyber-enabled economic coercion from traditional cyber-espionage, including intelligence gathering for advantage in economic negotiations. While the United States should not tolerate adversaries’ espionage operations, they warrant a different response than attempted (or successful) coercion.

Mass Collection of Personally Identifiable Information

Since China’s 2014 hacks of the Office of Personnel Management and health insurance company Anthem, Chinese cyber actors have only increased efforts to steal the personally identifiable information,38 personal health information,39 and financial records40 of U.S. citizens.41 In 2020, the Department of Homeland Security assessed that China will continue to use “cyber espionage to steal … personally identifiable information (PII) from U.S. businesses and government agencies to bolster their civil-military industrial development, gain an economic advantage, and support intelligence operations.”42

While the long-term objectives of these data breaches are not entirely clear, U.S. officials and analysts theorize that China is building a large database of U.S. citizens to identify targets for espionage operations, such as military members, federal employees, or executives in strategic industries.43 This could amplify the impact of both commercial espionage and CEEW.

China’s data harvesting may also advance China’s artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities. AI needs large data sets on which to train to compute faster and develop more useful insights.44 The National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence warned that “adversaries’ systematic efforts to harvest data on U.S. companies, individuals, and the government is about more than traditional espionage.” Illegally acquired data combined with commercial data could enable China to “monitor, control, and coerce” individuals beyond its borders. The report warns, “Personal and commercial vulnerabilities become national security weaknesses as adversaries map individuals, networks, and social fissures in society; predict responses to different stimuli; and model how best to manipulate behavior or cause harm.”45

China Seeks Control of ICT

Control of global ICT infrastructure and its constituent technologies, supply chains, and services is a central front in the competition between Washington and Beijing. ICT includes 5G and other telecommunications equipment as well as satellite navigation, cloud computing, and integrated circuits. Leadership in this field figures prominently in each country’s long-term economic and military development.

China’s 14th Five Year Plan (FYP), announced in March 2021, is a key indicator of Beijing’s global ambitions in ICT.46 The country’s National Medium- and Long-Term Plan for the Development of Science and Technology (2006–2020),47 the 13th FYP,48 and Made in China 202549 have all stressed the need for China to adopt an “innovation-driven” economic model. The 14th FYP, however, demonstrates a marked shift in tone, stressing a reduction in Chinese dependence on foreign technology through greater “self-reliance.” The 14th FYP makes clear China’s future economic and national security are inextricably linked to control and influence over the global technology environment. Most importantly, the CCP believes that U.S.-controlled or dominated global ICT industry threatens China’s national security.

In Beijing’s view, the United States has abused its leadership in ICT to conduct global surveillance, undercut China’s economic ambitions, and thereby stymie China’s rise. The contents of the Edward Snowden leaks in 2013, which alleged the United States leveraged its technology companies for global surveillance and reconnaissance, remain a lens through which China views the battlespace. Its strategic literature is rife with information security concerns stemming from U.S. dominance in technology. Chinese officials have repeatedly dismissed U.S. concerns about Huawei, ZTE, and other PRC national champions as hypocritical.50 In response to tariffs and increased export controls on Chinese semiconductors, Chinese officials also accused Washington of protectionism.51

Such accusations draw a false equivalence between U.S. and Chinese actions but reflect Beijing’s goal of controlling the ICT infrastructure. As such, China has poured billions of dollars into the expansion of its ICT industry, to include 5G and semiconductors. In 2019, China established an Advanced Manufacturing Fund of $20.9 billion52 and a National Semiconductor Fund of $28.9 billion.53 In 2020, China’s foremost producer of integrated circuits, the Semiconductor Manufacturing International Co., received $2.25 billion in financing from state-backed funds.54 Additionally, in response to expanded U.S. export controls, the Finance Ministry introduced a two-year waiver on corporate tax payments for software developers and integrated circuit manufacturers.55

Huawei, the bellwether of China’s tech giants and a perennial target for those concerned about Chinese influence over ICT, best illustrates the role of state financing. According to The Wall Street Journal, Huawei has received more than $75 billion in state-backed aid, including more than $45 billion in loans and credit lines from government lenders, tax breaks worth $25 billion, $1.6 billion in grants, and $2 billion in land discounts.56 This has allowed the company to invest far more in research and development than its competitors, including some $15 billion in 2018.57 Additionally, subsidies and preferential financing have allowed Huawei to lower its prices, undercutting competitors by up to 30 percent in a bid to achieve rapid market penetration and expand globally.58

When the United States pushed its allies to restrict Huawei’s entry into their 5G infrastructure, they initially balked at the higher prices of other providers.59 Washington was ultimately successful and reduced Huawei’s global market share,60 but it will take a similarly significant diplomatic campaign (combined with export controls or other restrictions that reduce Chinese access to critical component technology) for the United States to push back against China’s efforts to control other parts of the global ICT infrastructure and supply chain. If, for example, China were to establish a microchip production capability on par with that of Western companies, Beijing would likely try to control exports of raw materials, undercut market prices, and otherwise undermine Western firms to drive them from the field.61

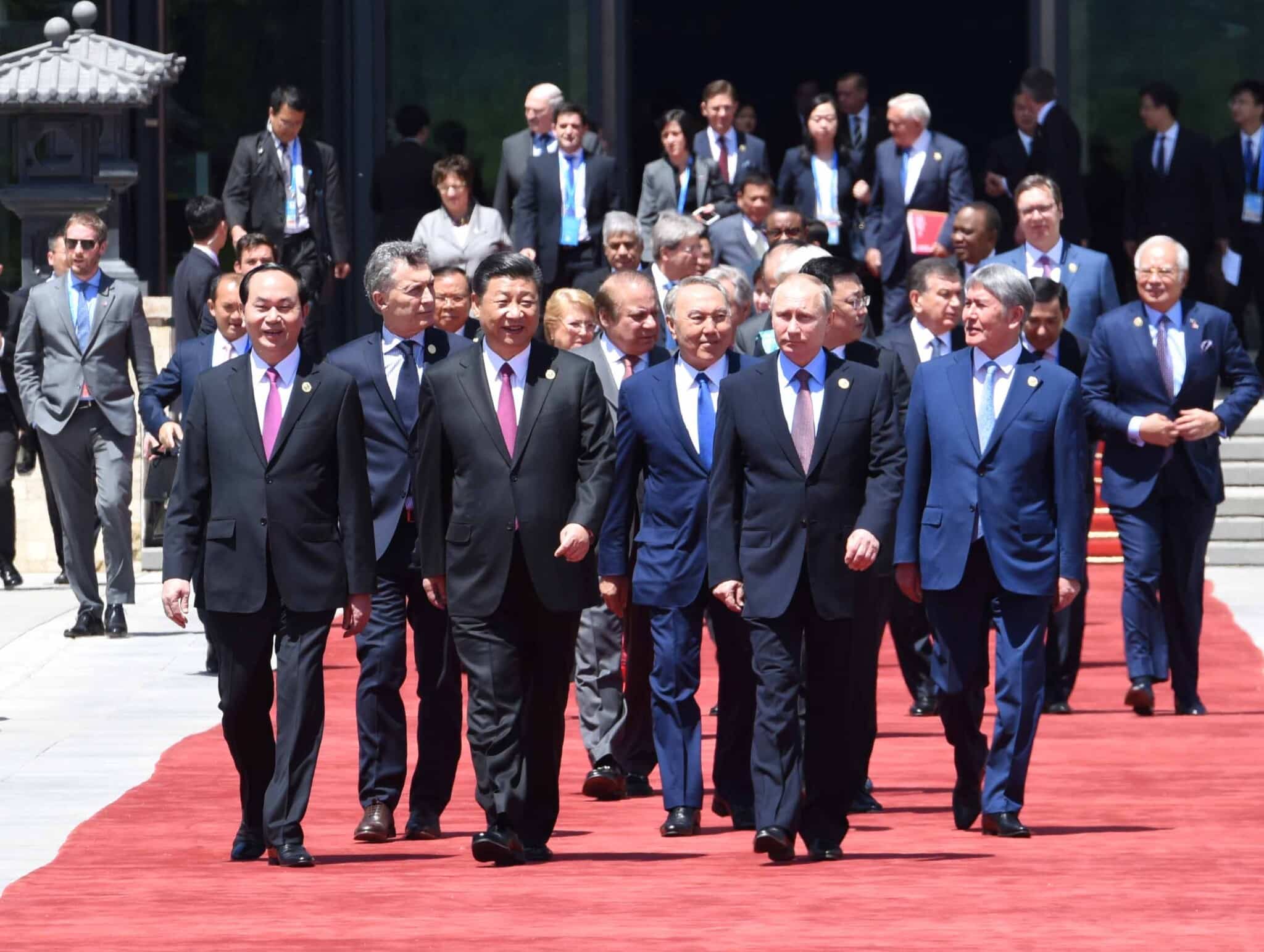

Chinese leader Xi Jinping meets with foreign delegation heads and guests after the first session of the Leaders’ Roundtable Summit at the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation on May 15, 2017, in Beijing, China. (Xinhua/Rao Aimin via Getty Images)

The CCP’s foreign aid and development strategies also support its desire to dominate in ICT. The Digital Silk Road (数字丝绸之路; DSR)62 campaign, an initiative Beijing launched in 2015 to complement the physical infrastructure projects of the Belt and Road Initiative (一带一路; BRI), focuses on building “China-centric digital infrastructure, exporting industrial overcapacity, [and] facilitating the expansion of Chinese technology corporations,” among other objectives.63 One of the DSR’s four major projects entails investing in “digital infrastructure abroad, including next-generation cellular networks, fiber optic cables, and data centers.”64 The DSR also provides support to tech giants such as Huawei, ZTE, and others to “pursue commercial business opportunities and be involved at all levels of the digital infrastructure built along the DSR.”65

Over the years, China’s IP theft has helped support the growth of its ICT sector. Huawei, for example, faces pending federal charges for theft of trade secrets, sanctions evasion, and racketeering.66

Finally, China promotes global technical standards to support its ICT strategy. Standards confer first-mover advantages on the companies that propose them. Companies earn royalties from standards-essential patents, potentially a significant source of revenue for Chinese companies. At the same time, Beijing is using its influence in these forums to undermine human rights and privacy in the ICT ecosystem by promoting technical standards that facilitate government surveillance.67

Surveillance and Data Collection

The United States and its allies recognize the risks of allowing Chinese technology companies into their markets. When the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) denied China Mobile’s application to provide telecommunications services in the United States, then-FCC Chairman Ajit Pai warned that “if this application were granted, the Chinese government could use China Mobile to exploit our telephone network to increase intelligence collection against U.S. government agencies and other sensitive targets that depend on this network.”68

Both the U.S. and allied governments have reportedly found evidence of Huawei equipment being used for such purposes.69 In 2019, Dutch intelligence launched an investigation into Huawei’s role in espionage. Dutch security chief Dick Schoof pointedly stated that “when it comes to our vital infrastructure or 5G, we say: you should not want to buy hardware and software from countries that have an offensive cyber program aimed at Dutch national security.”70 Annual reports from a British oversight board that evaluates Huawei-related infrastructure security risks consistently raise concerns about the engineering and cybersecurity of Huawei products and the company’s failure to address previous concerns.71 While these reports have not accused the CCP of leveraging Huawei for espionage or other nefarious purposes, Downing Street banned the company from core 5G infrastructure after deeming it a “high-risk vendor.”72 Meanwhile, when Sweden’s Post and Telecom Authority banned Huawei from its 5G infrastructure, it noted, “The Swedish Security Service judges that the Chinese state and security services can influence and exert pressure on Huawei.”73

One driver of these concerns is China’s National Intelligence Law, which grants Chinese intelligence agencies broad authority to co-opt or compel any company, including China’s tech giants, to assist with national intelligence work.74 The law creates, in the words of one Chinese legal scholar, “affirmative legal responsibilities for Chinese and, in some cases, foreign citizens, companies, or organizations operating in China to provide access, cooperation, or support for Beijing’s intelligence-gathering activities.”75 Beijing could demand that technology companies hand over information on foreign citizens, enable government access to databases or software, or install “backdoors” in their software that intelligence agencies can exploit.

Forced Technology Transfer and ‘De-Ciscoization’

Beijing has steadily increased restrictions on foreign ICT companies operating in China even as its own companies have expanded their international presence. Over the last two decades, China has issued several laws, regulations, and policies that disadvantage foreign firms relative to their Chinese counterparts, particularly in the ICT sector.76 These measures have included forced joint ventures, technology transfer requirements, and weak enforcement of IP rights. State policies, such as Made in China 2025, “explicitly [aim] to develop advanced technologies while excluding foreign firms from Chinese markets for those technologies,” according to Jeff Moon, former assistant U.S. trade representative for China.77

These efforts accelerated after the Snowden revelations, with some commentators calling for the “de-Ciscoization” (去思科化) of Chinese networks — that is, the removal of all U.S.-sourced technology.78 Subsequently, U.S. companies operating in China have been subject to new measures under the National Cybersecurity Law of 201579 and the National Encryption Law of 2019,80 which entail source code reviews, opaque security regulations, and exclusions from certain Chinese networks. These measures have reduced foreign firms’ ability to compete in China. For Chinese companies, a privileged position in China’s large domestic markets complements the extensive subsidies they receive from the government.

Attacks on and Through ICT Products

China is simultaneously promoting “information technology companies that could serve as espionage platforms” and conducting cyber operations against global ICT firms “whose products and services support government and private-sector networks worldwide,” according to a 2020 Department of Homeland Security report.81 China is “compromising telecommunications firms, providers of managed services and broadly used software, and other targets potentially rich in follow-on opportunities for intelligence collection, attack, or influence operations,” echoed the U.S. intelligence community in April 2021.82

Compromising a popular product or service provider enables Beijing to penetrate the firms that depend on it. For example, in the case of Operation Cloud Hopper, which began in 2014, Chinese hackers compromised managed service providers to penetrate hundreds of companies worldwide and across numerous industries.83 In 2017, suspected Chinese cyber actors inserted a backdoor into an update for CCleaner software, enabling access to the reportedly 2.7 million machines that downloaded the malicious patch.84 Hackers then selected 40 affected IT companies, including Samsung, Sony, Intel, and Fujitsu for “second-stage” intrusion.85

In 2021, China twice exploited vulnerabilities in Microsoft Exchange Servers to access victims’ networks, emails, and calendars.86 By the time Microsoft patched the vulnerabilities, Chinese and other hackers had compromised tens of thousands of individual servers worldwide, including over 30,000 in the United States alone.87 Separately, suspected Chinese cyber actors exploited the Pulse Secure virtual private network to compromise government agencies, defense contractors, and financial institutions across America and Europe.88

These attacks represent a substantial advance in Chinese cyber operational planning, demonstrating a prioritization of pervasive access through supply chain compromise rather than blunt spear phishing or exploitation of an individual target. Such attacks are difficult to detect and attribute. Even if an intrusion is discovered, one still must determine the origin of the initial compromise. For Beijing, such attacks have exceptional value because they enable persistent access, sustained collection, and tailored operations. They also reflect a broader shift from a “target-centric” strategy towards a “capability-centric” strategy, through which Beijing can pursue multiple CEEW objectives at once: economic espionage, economic coercion, critical-infrastructure disruption, and collecting personally identifiable information.

Recommendations

In Washington, recognition of the CEEW threat has grown substantially since FDD published its initial report on Chinese CEEW four years ago. Congress has passed a number of bipartisan measures since 2018, such as the Export Control Reform Act and key provisions in the FY2021 NDAA, that strengthen America’s ability to defend against Chinese CEEW and malicious cyber operations more broadly. However, gaps still remain. Properly addressing Chinese CEEW will require sustained effort.

- Implement sanctions and other measures to curb Chinese cyber-enabled IP theft. The United States must impose material costs on the Chinese individuals and entities that have directed or benefitted from cyber-enabled IP theft or perpetrated acts of CEEW. The threat of U.S. sanctions was instrumental in pressuring the Chinese ahead of the Xi-Obama agreement that temporarily reduced Chinese cyber-enabled IP theft.89 A healthy future for the U.S.-China trade relationship will depend on guarantees from Beijing to adhere to global IP protections. It will also require transparency and reciprocity for U.S. firms operating in China, granting them the same legal standing as domestic firms in IP infringement cases.

- Ensure the Continuity of the Economy. The United States must mitigate or stave off the consequences of CEEW operations, particularly critical infrastructure disruption. China has demonstrated both the intent and capability to put U.S. critical infrastructure at risk. As China increases the scale and sophistication of its cyber capabilities, the United States should expect an increase in targeting of critical assets. While the United States plans well for military contingencies and natural disasters, it lags in planning for CEEW scenarios. In the FY2021 NDAA, Congress passed a provision for Continuity of the Economy (COTE) planning, which directs the U.S. government to develop contingency plans to rapidly restart the economy in the event of a systemic disruption.90 The legislation directs the U.S. government to focus on key mechanisms and critical industries so that in the event of conflict, the United States can blunt the effects of attempted coercion and maintain freedom of action. More than a year later, the federal government has barely begun. It must rapidly stand up the planning effort and ensure the necessary interagency and budgetary support.

- Prepare offensive economic contingency plans. Whereas COTE planning is defensive in nature, the United States should also consider economic actions that impose costs on attackers. China’s approach to conflict will not conform to conventional American views of war. For now, China remains wary of provoking the United States into an armed confrontation, particularly as its military forces still lag those of the United States. China is therefore likely to utilize a combination of cyber-enabled economic coercion and targeted critical-infrastructure disruption to pressure the United States or its allies. As Cooper noted in 2018, “Chinese activity across a range of domains operates in the ‘gray zone’ below the threshold that would warrant a major and sustained response. China uses asymmetries, ambiguity, and incrementalism to advance its strategic and economic aims without triggering a conflict with the United States or its friends.”91

Accordingly, the U.S. government must plan for economic contingencies vis-à-vis China. These plans should be formed alongside, and informed by, the key scenarios that guide U.S. military contingency planning. The United States cannot be caught flat-footed in responding to China’s CEEW and broader political warfare. - Establish a plurilateral approach to export controls. In recent years, the United States has implemented measures to limit Chinese ICT development and the risk these technologies pose to U.S. critical infrastructure. Export controls on semiconductors, for instance, have precipitated a substantial loss in market share for Huawei and other Chinese companies.92 The Department of Commerce has added Chinese firms to its Entity List, which deprived them of basic American-made technologies necessary to expand their industrial output.93 However, China will likely resort to CEEW measures to circumvent these restrictions, either through IP theft or by employing a mix of coercion and persuasion to secure the desired technology from a U.S. ally. Thus, for export controls to be effective, they must be plurilateral. Such controls mean little if America’s other trading partners allow China access to technology the United States seeks to restrict.

- Codify into law measures against high-risk Chinese vendors. Executive Order 13873, “Securing the Information and Communications Technology and Services Supply Chain,” signed on May 19, 2019, is one of the broadest and most powerful tools the United States can wield to combat risks associated with Chinese ICT in U.S. critical infrastructure.94 The order delegates significant authority to the secretary of commerce to mitigate risks and block transactions involving ICT and related services owned, controlled, or directed by “foreign adversaries,” to include China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, Cuba, and Venezuela.

Despite its importance, this executive order rests on shaky ground. It relies on an emergency declaration under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, which the sitting president can revoke at any time. Emergency declarations, while expedient, are not a substitute for statutory action when facing an enduring risk to national security. The measures envisioned under the executive order should be made permanent through codification in law. With statutory authorities, the Commerce Department could establish a quasi-“import control” regime around ICT equipment to reduce the risk of cyber-enabled IP theft and critical-infrastructure disruption facilitated by firms under U.S. adversaries’ control.

Conclusion

The Chinese approach to CEEW reflects Beijing’s perception of its vulnerabilities and strengths. The CCP seeks to establish China as a global center of innovation and economic power but anticipates foreign resistance to that goal. The 14th FYP, issued in March 2021, “highlights a growing urgency to protect China from external vulnerabilities through attaining self-reliance in science and technology,” in the words of one China analyst.95 This is a direct response to U.S. trade and export-control measures that underscore China’s weakness in indigenous innovation. Yet the CCP is unlikely to revisit the confrontational approach that spurred this American response. On the contrary, Beijing’s strident foreign policy and rhetoric make clear that CEEW will continue to be a mainstay of Chinese statecraft for years to come.