June 5, 2020 | Insight

COVID-19 in Iran and Turkey: Mismanagement, Crackdowns, Economic Crises, and Corona-Diplomacy

June 5, 2020 | Insight

COVID-19 in Iran and Turkey: Mismanagement, Crackdowns, Economic Crises, and Corona-Diplomacy

Iran and Turkey have been the two countries in the Middle East hardest hit by COVID-19. Their respective epidemics – which both governments have largely mismanaged – have amplified their democratic deficits, compounded their economic crises, and prompted failed diplomatic offensives.

Mismanagement

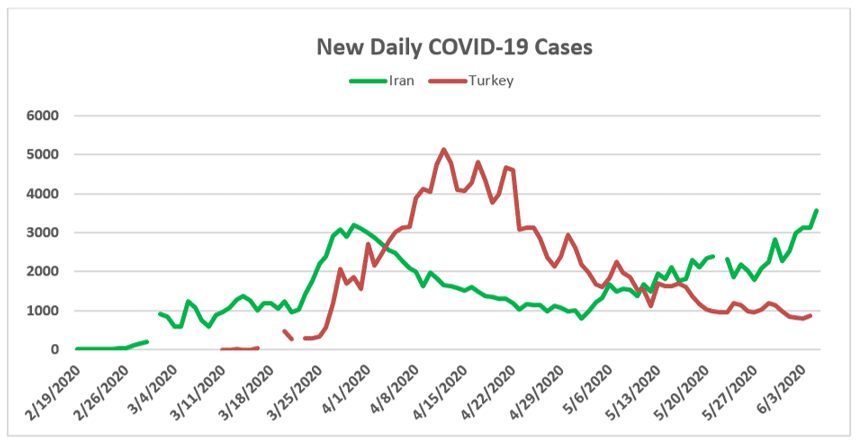

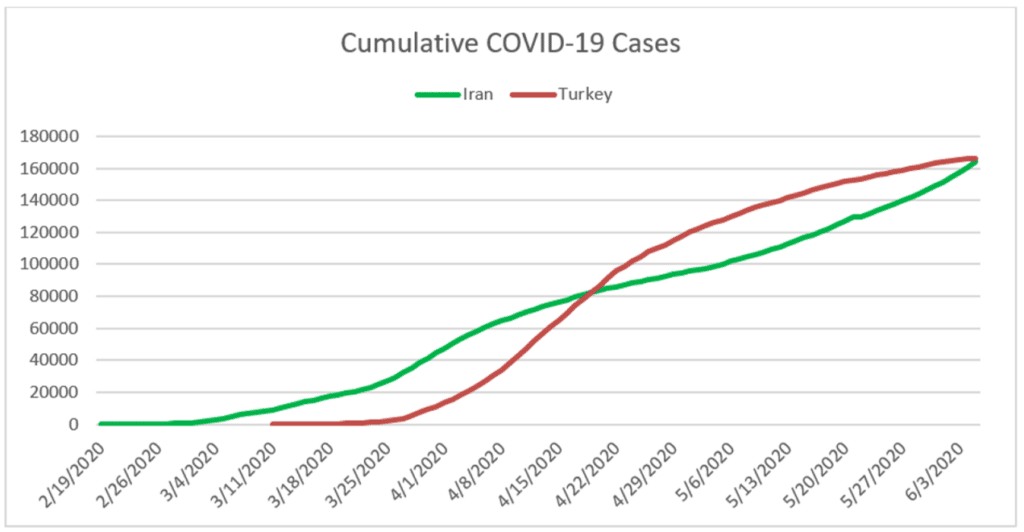

Iran and Turkey, the two most populous countries in the Middle East, with some 84 million people each, also lead the region in confirmed COVID-19 cases. Iran, which reported its first case on February 19, has over 167,000 cases as of June 5, the 12th-highest in the world. Turkey, which reported its first case on March 11, three weeks after Iran, ranks 11th worldwide, with some 168,000 cases.

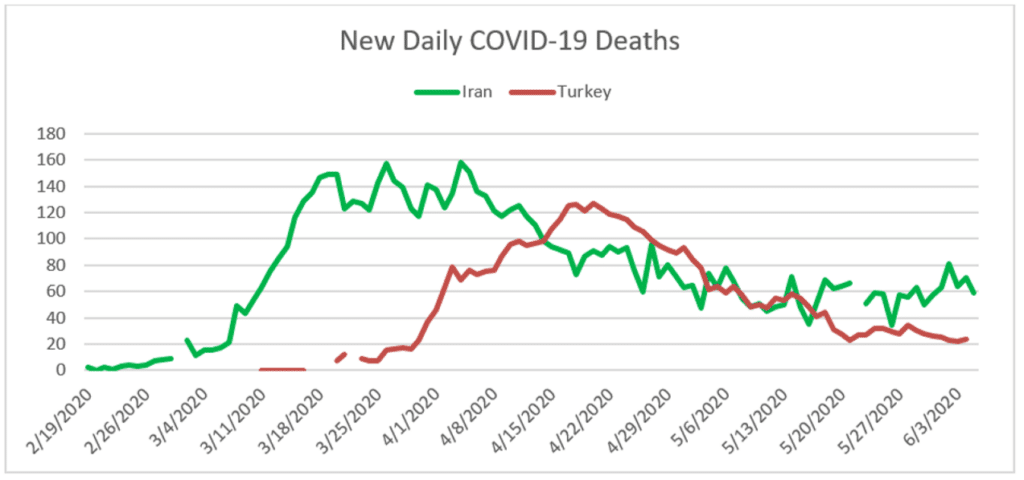

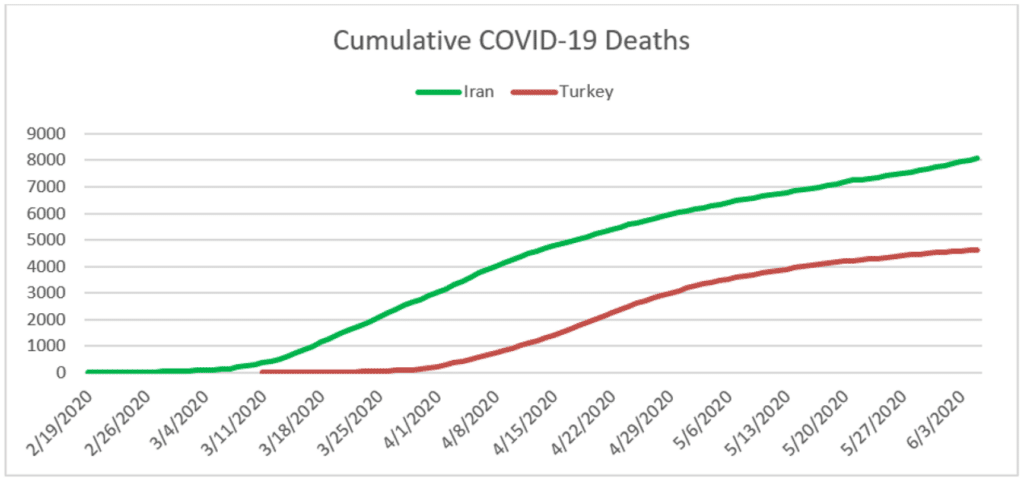

Their real numbers are likely much higher, however, since Iran and Turkey both consistently underreport their COVID-19 cases. Although the Iranian cabinet first discussed the coronavirus in a meeting on January 17, the regime waited another month before finally admitting the virus had entered Iran. Even then, Tehran continued to restrict public discussion of the pandemic. The Islamic Republic has systematically underreported COVID-19 fatalities by filing them as caused by “severe respiratory disease,” a practice criticized even by an Iranian lawmaker. Iran’s systematic cover-up has triggered a second wave of the epidemic. On June 3, Tehran reported its highest number of daily COVID-19 infections in two months.

Turkey has similarly underreported COVID-19 cases, by limiting testing early on and excluding clinically diagnosed cases from its overall statistics. A number of studies using publicly available mortality statistics revealed significant spikes in Turkish COVID-19 fatalities, which started to rise even before the country’s first confirmed coronavirus death.

Political Islam contributed to inadequate mitigation measures by both governments. Even after acknowledging its first COVID-19 cases in Qom, a holy city for Shiite Muslims, the clerical regime in Iran refused to quarantine the city or its religious centers. Only in March did Tehran finally close the Masoume Shrine, an order defied by worshippers.

Similarly, Ankara not only failed to stop religious pilgrimage trips to Saudi Arabia in late February, but was also late to quarantine some 21,000 pilgrims on their return home and waited until March 16 before suspending communal prayers. These failures – made at the behest of Turkey’s powerful Directorate of Religious Affairs and designed to please President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Islamist base – contributed to the spread of the virus.

For what it is worth, however, Ankara’s approach has not been as poor as Tehran’s. Turkey’s minister of health shares daily updates on the country’s total number of tests, reported cases, recoveries, and fatalities. In addition, Turkey has imposed much stricter lockdown measures than has Iran. As of May 31, Turkey had a rating of 78.7 (out of a possible 100) on Oxford’s Government Response Stringency Index, as opposed to Iran’s rating of 55.6.

Ankara started cancelling flights to China on January 30 and suspended all flights from the pandemic’s epicenter on February 5, but waited until February 23 to close its land border with Iran, the pandemic’s regional epicenter. Turkey restricted passage of trucks and freight trains and closed its main route for trade with Iran, the Bazargan/Gurbulak station, which it replaced with the nearby Sarisu border crossing. Ankara announced its plans to reopen the Bazargan/Gurbulak border gate on June 3, the day Tehran reported its second wave of COVID-19 infections.

Meanwhile, Iran’s Mahan Air, which the U.S. Treasury Department designated in 2011 for “providing financial, material and technological support to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Qods Force (IRGC-QF),” continued flights to China even after Tehran officially suspended them on January 31. Mahan conducted at least 55 return flights from China between February 4 and February 23.

Political Crackdowns

Iran and Turkey’s Islamist leaders have both sought to exploit the COVID-19 crisis to tighten their grip on power. Nazanin Boniadi, a member of the board of directors at the Center for Human Rights in Iran, warns that the COVID-19 epidemic is “exacerbating the government’s assault on the rights of Iranian citizens.” Similarly, Brookings Senior Fellow Kemal Kirisci has observed that COVID-19 “has led to more authoritarianism for Turkey.”

For both Tehran and Ankara, political concerns have overridden public health priorities. Fearing that COVID-19 would lead to a massive outbreak in prisons, Tehran announced on March 9 the temporary release of 70,000 prisoners, but excluded political detainees. That number reached 85,000 by March 17, with the release of some political prisoners. Similarly, Turkey passed a bill on April 14 to release some 90,000 inmates, including mob bosses, racketeers, and looters, but kept political prisoners behind bars, including scores of lawmakers, mayors, and opposition officials.

Furthermore, both countries have doubled down on their longstanding political repression. As of April 28, the regime in Iran had arrested 3,600 Iranians under a new law that makes spreading “fake news or rumors” about COVID-19 punishable by up to three years in prison.

True to form, the Turkish government, the world’s top jailer of journalists, has interrogated journalists for reporting on COVID-19 – even filing a criminal complaint against a local TV news anchor for “spreading lies and manipulating the public.” Turkish authorities have also arrested over 400 individuals for allegedly inflammatory social media posts. The Erdogan regime also removed eight opposition mayors from office on March 24 and stripped three opposition lawmakers of their parliamentary status before arresting them on June 4.

In both countries, authorities have sought to scapegoat minorities for COVID-19, with Ankara demonizing the LGBTI community and Tehran going after, as usual, Jews.

Economic Impact

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts that this year the Iranian and Turkish economies will shrink by 6 percent and 5 percent, respectively. For Iran, this would mark its third consecutive year of economic contraction. For Turkey, which seemed to have shaken off recession during the third quarter of 2019 after three consecutive quarters of contraction, this means a return to economic malaise.

Even before the pandemic, Iran’s economy was ailing as a result of Washington’s maximum pressure campaign. The pandemic has further depressed economic activity in Iran, widening the country’s trade deficit. Iran will likely see a current account deficit of 4 percent this year.

Given their already tight financial situations, neither Iran nor Turkey was able to offer substantial aid packages to soften the economic pain of COVID-19. Tehran has had a cash subsidies system in place since 2010, but these transfers amount to just $11 per month at the official exchange rate. With no relief in sight, millions of Iranians were left with no option but to go to work.

Empty coffers similarly prevented the Turkish government from offering substantial assistance to its citizens. The $15 billion stimulus plan Ankara announced on March 18 amounted to 1.5 percent of Turkish GDP. The Turkish government has since increased the stimulus to 5 percent of GDP, but this figure still pales in comparison to packages issued by other states, including Japan (21 percent), the United States (11 percent), and Brazil (8 percent). In the absence of greater stimulus, Ankara needed to keep the wheels of the economy turning. Hence, it imposed few restrictions on the movement of the working-age population despite calls from the opposition and unions for a lockdown.

Coronavirus Diplomacy

Both Tehran and Ankara have launched charm offensives through coronavirus diplomacy to restore their global public images. Although Iranian and Turkish healthcare workers have frequently complained about shortages of personal protective equipment, both countries have made it a priority to direct medical supplies abroad.

In January and February, Tehran sent millions of masks to China. Ankara similarly airlifted its first shipment of medical aid to China in early March, then sent shipments to Iran on March 17. At the end of May, Ankara claimed to have received requests for assistance from 135 countries and sent medical aid, including face masks, gloves, and ventilators, to 100 countries. Iran and Turkey’s charm offensives collided on May 11, when Turkish diplomatic sources refuted Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif’s claim that Tehran “sent 40,000 advanced Iran-made test kits to Germany, Turkey and others.”

The United States was a key target of both Tehran’s and Ankara’s coronavirus diplomacy, albeit in different ways. The Islamic Republic used the pandemic to initiate a disinformation campaign to pressure Washington to suspend its sanctions. The clerical regime’s central claim was that sanctions had deprived Iranians of pharmaceutical products needed to fight the virus, a claim not supported by trade data, which show that sanctions have not significantly affected Tehran’s pharmaceutic imports.

In contrast, Erdogan launched a charm offensive by sending two military planeloads of medical aid to the United States, alongside a letter praising President Donald Trump’s “spirit of solidarity” during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Ozgur Unluhisarcikli, the director of the Ankara office of the German Marshall Fund, Ankara was seeking “a quid pro quo likely to include the further delay of any US sanctions for its purchase of a Russian air defence system, and a dollar swap line from the Federal Reserve.” So far, Washington has not expressed any willingness to accommodate either of Ankara’s requests.

The Outlook

Despite their attempts to consolidate power, the COVID-19 crisis will continue to delegitimize the Iranian and Turkish regimes. In both countries, the economic crises triggered by the pandemic and amplified by government mismanagement and corruption have exacerbated discontent and fissures within their respective societies.

While Iran will continue to suffer from a collapse in both oil revenue and non-oil exports, Ankara has the option of signing a bailout deal with the IMF and initiating structural reforms to start remedying Turkey’s economic woes. Nevertheless, Ankara is unlikely to pursue an IMF program, since Erdogan sees IMF conditionalities requiring transparency, accountability, independent regulatory agencies, and an autonomous central bank as inimical to his hyper-centralized style of governance and extensive patronage network.

Aykan Erdemir is a former member of the Turkish parliament and the senior director of the Turkey Program at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), where Saeed Ghasseminejad is a senior Iran and financial economics advisor. They both contribute to FDD’s Center on Economic and Financial Power (CEFP), Iran Program, and Turkey Program. For more analysis from Aykan, Saeed, CEFP, and the Iran and Turkey Programs, please subscribe HERE. Follow Aykan and Saeed on Twitter @aykan_erdemir and @SGhasseminejad. Follow FDD on Twitter @FDD and @FDD_CEFP and @FDD_Iran. FDD is a Washington, DC-based, nonpartisan research institute focusing on national security and foreign policy.