January 14, 2021 | From Trump to Biden Monograph

Cyber

January 14, 2021 | From Trump to Biden Monograph

Cyber

Current Policy

After the publication of the 2018 National Cyber Strategy, the Trump administration pushed agencies across the U.S. government to develop strategies, policies, and programs that aligned with and supported the national strategy.1 Despite uneven implementation across the interagency and recent revelations about a devastating cyberespionage campaign against the public and private sectors, the federal government did improve its collaboration with industry, state and local governments, and allies and partners. Such cooperation is critical to deter, combat, and recover from catastrophic cyberattacks.

Under Trump, the Department of Defense (DoD) continued its improvement of cyber capabilities. In its 2018 Defense Cyber Strategy, DoD articulated a “Defend Forward” strategy to disrupt or degrade malicious cyber activity at its source.2 This proactive approach improved America’s position in the cyber battlespace by leveraging U.S. Cyber Command’s “persistent engagement” concept.3 The new strategy also drew support from legislation that established cyber surveillance and reconnaissance as a traditional military activity, and from National Security Presidential Memorandum 13, which authorized offensive cyber operations.4 Despite the mandate to operate on non-U.S. networks, Defend Forward – as its name suggests – is a defense-oriented strategy, seeking to neutralize imminent threats before attacks are launched. DoD also invested in the defense of its own networks and provided increasing support to the Defense Industrial Base (DIB), while demanding that the DIB improve its own network and supply chain security.

Christopher C. Krebs, then-director of the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, speaks before the Senate Judiciary Committee on May 14, 2019. (Photo by Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images)

On the civilian side, numerous federal agencies – identified as Sector Specific Agencies (SSAs) in Presidential Policy Directive 21, which focused on critical infrastructure security and resilience – leveraged their unique capabilities and relationships with private industry to improve the reliability of associated infrastructure. The Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) emerged as the leader of the federal effort to shore up communications infrastructure and was a prominent point of collaboration across the government and between the public and private sectors.5 Other agencies performed similar roles within their sectors: The Department of Energy (DOE), for example, ramped up its emergency response efforts through its Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response and funded innovative cybersecurity research at the National Labs.

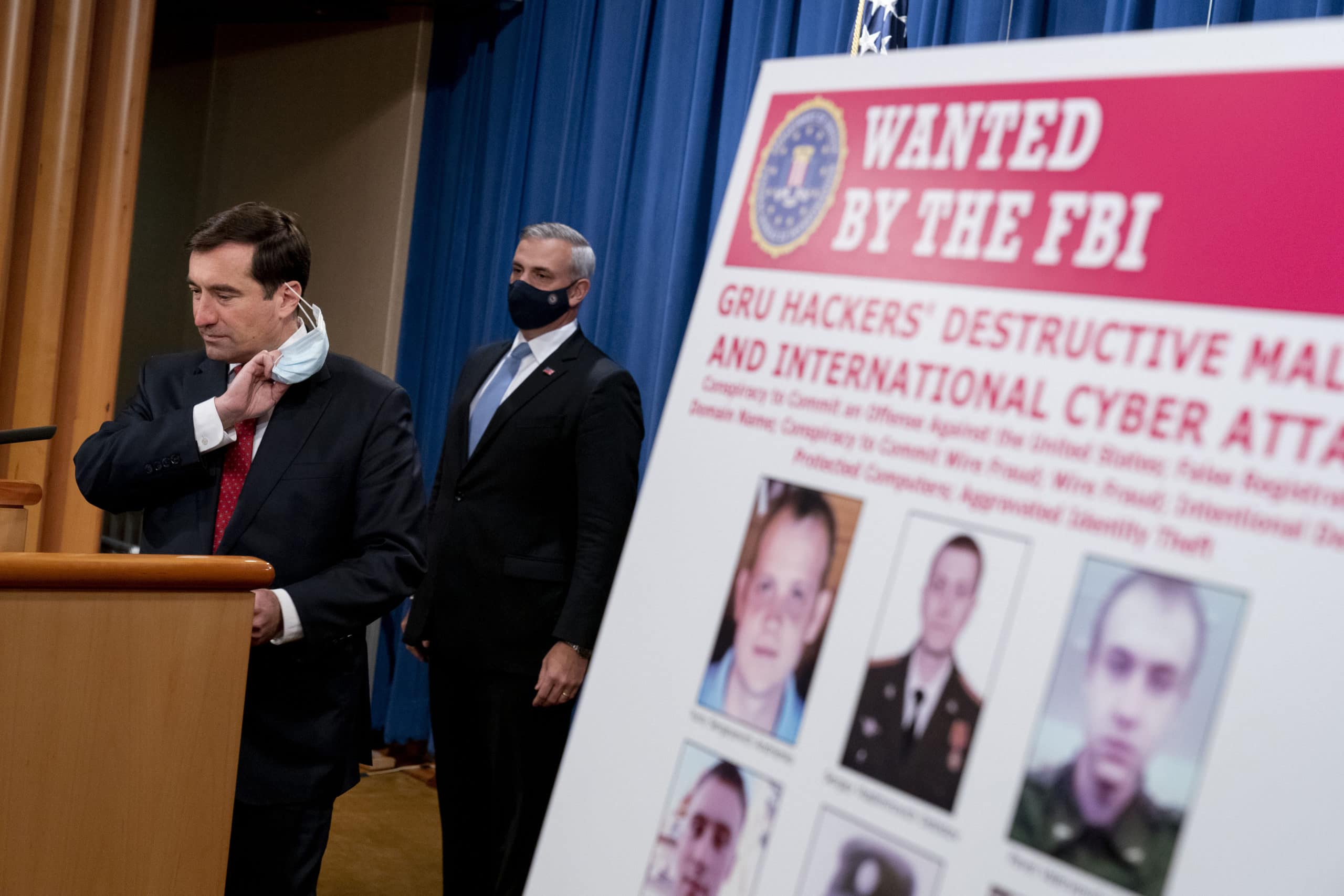

On the law enforcement side, federal agencies imposed costs on malicious actors through criminal prosecutions, asset freezes and seizures, and the destruction of operational infrastructure.6 These agencies also enhanced cooperation with state and local officials to defend networks and recover from attacks.

Internationally, the U.S. government had limited success in its efforts to secure global communications infrastructure through its Clean Network program.7 This State Department-led initiative sought to build partnerships with industry and governments around the world to promote the use of equipment, software, cloud services, and other technology free from the Chinese Communist Party’s malign influence.

While cyberattacks continue unabated, there is now greater awareness not only of the scale of the threat, but of its nature as well. Following its official recognition in the 2017 National Security Strategy, the concept of “cyber-enabled economic warfare” has become widely accepted as the most apt descriptor of a significant component of adversary activity in cyberspace.8

Against this backdrop, the Cyberspace Solarium Commission (CSC), which Congress chartered in 2018 to develop a strategic approach to defend against significant cyberattacks,9 developed a new strategic approach: layered cyber deterrence.10 This strategy emphasizes investing in the security and resilience of the networks that underpin national critical infrastructure, improving public-private collaboration, and expanding Defend Forward’s focus to include all elements of government power. This layered approach will enable the United States to more effectively impose costs, deny benefits, and shape behavior in cyberspace.

Assessment

While the Trump administration made strides to better defend military, civilian, and private-sector networks from malicious cyber actors, a lack of leadership at the national level undermined coordination and the implementation of the National Cyber Strategy.11 Public-private collaboration did not develop sufficiently, with the government struggling to establish the shared analytical capabilities, information sharing instruments, and planning mechanisms necessary to support a collaborative environment. The performance of SSAs was inconsistent, leaving some sectors, such as water production and distribution, vulnerable to cyberattacks.

Other shortcomings were the result of insufficient resourcing. While CISA enjoyed important successes, it struggled to operationalize the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center and stand up the National Risk Management Center. The former’s mission is to analyze threats to cyber and communications infrastructure, develop shared situational awareness among partners and constituents, and lead the national response to cybersecurity incidents. The latter leads efforts to prioritize and manage risks to critical infrastructure. The administration and Congress did not properly resource the State Department’s Cyber Deterrence Initiative, while DoD still sizes its Cyber Mission Force – the operational arm of U.S. Cyber Command – based on the mission set and threats from 2012 assessments.

The CSC identified the lack of leadership and resourcing as two of the central challenges impeding effective U.S. response to cyber threats.12 Leadership and proper resourcing are also essential to implement one of CSC’s core recommendations: the development of a Continuity of the Economy (CotE) plan to reconstitute core economic functions in the aftermath of a cyber event that causes systemic disruption. During the Cold War, the United States developed contingency plans to ensure that essential government functions continued in the event of a nuclear exchange. In the digital age, a significant cyber event could have an equally disruptive effect on the American way of life, particularly if it results from a series of cyber-enabled economic warfare attacks.

The shortcomings of U.S. policy were particularly problematic in light of the persistent and increasing efforts of China, Russia, North Korea, Iran, and non-state actors to exploit network insecurity to steal, disrupt, destroy, or subvert U.S. critical infrastructure and supply chains. Information technology (IT) supply chain attacks are becoming more prevalent, with hackers leveraging the trusted access of third-party vendors to penetrate their clients’ networks. While the U.S. government endeavored to educate the private sector about this threat, the widespread and long-term Russian intelligence operation exploiting IT provider SolarWinds revealed significant shortcomings in the government’s own defenses.

A poster showing six wanted Russian military intelligence officers is displayed as Assistant Attorney General for National Security John Demers (L) takes the podium at a news conference at the Department of Justice on October 19, 2020. (Photo by Andrew Harnik – Pool/Getty Images)

Beyond cyberespionage, North Korea and Iran continued to use cyber operations to generate funds for their regimes and as a tool of coercion and deterrence against the United States and its allies. Russia and China also continued to conduct cyber theft, but the greater threat is their efforts to create the conditions to destabilize U.S. critical infrastructure during a crisis. Moscow uses cyber and information operations to undermine Western institutions, and Beijing’s global campaigns undercut U.S. economic and strategic capabilities. Both countries are suspected of planting malware in critical infrastructure. The United States must thus understand cyberattacks as part of larger strategic goals and develop policies to address these broader challenges rather than behavior exclusively in the cyber domain.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the far-reaching impact of major disruptive events on the lives of all Americans. The challenges government agencies experienced in responding to the non-traditional national security threat of the pandemic are likely to be repeated when mitigating or recovering from the disruptions caused by a significant cyber event.

Recommendations

- Properly organize and resource the government. Congress and the Biden administration should better organize and resource the government to implement layered cyber deterrence. Specifically:

- The White House needs a national cyber director (NCD) to implement the National Cyber Strategy and lead policy development in collaboration with the private sector and allies and partners. Unlike the previous cyber coordinator position, which the Trump administration eliminated, the NCD should report directly to the president (not the national security advisor) and be empowered to ensure federal agency implementation of the president’s strategy and policies, to lead interagency cyber contingency planning and incident response, and to convene senior official meetings. An NCD will better position the government to assess the scope of hacking campaigns like SolarWinds, rapidly attribute their sources, and respond appropriately.

- Congress should increase CISA’s funding for administrative and programs support, codify its responsibilities in identifying, assessing, and managing national and sector-specific risks, and establish its ability to “threat hunt” on the “.gov” domain, which might have helped detect the SolarWinds breach sooner.

- The State Department needs an assistant secretary for cybersecurity and emerging technologies (CSET) and resources for the Cyber Deterrence Initiative.

- DoD needs to conduct a force structure assessment of the Cyber Mission Force to ensure it has the appropriate resources and personnel in light of growing mission requirements and increasing threats.

- Build national critical-infrastructure resilience. The federal government should establish a critical infrastructure resilience strategy and codify its own responsibilities for both national and sectoral (that is, energy, financial services, water, et cetera) risk management. These steps will support the development of a CotE plan. An infrastructure resilience strategy and CotE plan would then analyze the critical functions that support large sections of the economy; prioritize functions for response and recovery efforts; and assess how best to preserve the data upon which those systems rely.

- Enhance public-private collaboration. The U.S. government should develop a system (like the “Joint Collaborative Environment” described in the CSC report) to collect and share threat information across government and with industry. Strengthening CISA’s integrated cyber center and creating a new Joint Cyber Planning Office within CISA will enhance shared analysis of threat information and will enable joint development of plans, procedures, and playbooks to defeat adversarial campaigns.

- Synchronize efforts with allies and partners. The Biden administration should continue to improve the government’s capacity to rapidly share information with allies and partners on malicious activity, including attributing attacks, and taking actions to prevent the activity. This effort should also include working together to establish international norms and, within standard-setting organizations, to develop transparent, rules-based approaches to the management of technology-based systems. An assistant secretary of state for CSET would help enable these efforts.

- Support a better cyber ecosystem. The federal government should help increase the overall security of the cyber ecosystem by:

- developing a Bureau of Cyber Statistics to collect and assess data to inform policymaking and government programs;

- establishing a National Cybersecurity Certification and Labeling Authority for information and communications technology products;

- creating a Cyber Insurance Certification Institute to work with state-level regulators to develop certifications for insurance products;

- incentivizing small and medium-sized businesses and local governments to use secure, cost-effective cloud services; and

- establishing and seeking long-term funding for a DOE-wide AI Capability center tasked with collecting and disseminating cybersecurity best practices for AI, a necessity for this burgeoning field.13 DOE and its 17 National Labs are best positioned within the government to expand both the science and the cybersecurity best practices of AI to build a more secure cyber ecosystem.