February 15, 2023 | Monograph

Arsenal

Assessing the Islamic Republic of Iran’s Ballistic Missile Program

Contents

- Foreword

- Executive Summary

- Birth of the Iranian Ballistic Missile Program

- Ballistic Missiles in Iran’s National Security Strategy

- Iran’s Missiles in Action

- Unpacking Iran’s Arsenal

- The Domestic ‘Engine’ Propelling Iran’s Ballistic Missile Program

- The U.S. Policy Conundrum

- Policy Options

- Conclusion

- Appendix B

- Appendix A

- Appendix C

- Download

February 15, 2023 | Monograph

Arsenal

Assessing the Islamic Republic of Iran’s Ballistic Missile Program

Foreword

By Vice Admiral (Ret.) James D. Syring

America’s adversaries are committed to developing and deploying increasingly lethal missile systems that complicate U.S. foreign and defense policy and pose a threat to our partners, our regional interests, and our own national security. In addition to advances in missile technology by Russia, China, and North Korea, which certainly deserve attention, Washington cannot afford to ignore the Islamic Republic of Iran’s growing ballistic missile capabilities.

During my tenure as director of the U.S. Missile Defense Agency from November 2012 to June 2017, we worked with the military services, the combatant commands, other elements of the Department of Defense, and American industry to protect Americans from enemy ballistic missiles. We also worked with a host of regional allies and partners confronting the same missile threats.

Three years ago, Tehran fired ballistic missiles with considerable accuracy at bases housing U.S. troops in Iraq. More than 100 American service members suffered traumatic brain injuries, and the consequences could have been even worse. Last January, Tehran’s proxies in Yemen apparently used similar missiles in an attempted strike against a base in the United Arab Emirates housing American military forces. And at least twice last year, once in March and once in September, Iran launched ballistic missiles at targets in Iraqi Kurdistan, with the latter strike reportedly killing 13 people, including one U.S. citizen. These attacks demonstrate the increasing willingness of Tehran and its terrorist proxies to use these weapons.

The Islamic Republic and its proxies rely on ballistic missiles to punish and deter action against their regional terror networks. Missiles support Iran’s effort to evict America from the Middle East and coerce U.S. partners into accommodating the Islamic Republic. The United States must therefore develop better missile defense capabilities and other tools to degrade Iranian missile power. The establishment of Aegis Ashore sites in Romania and Poland as part of the European Phased Adaptive Approach is an important but insufficient step. Understanding the nature and drivers of the Iranian missile threat is a vital prerequisite for developing a comprehensive and effective response.

In “Arsenal: Assessing the Islamic Republic of Iran’s Ballistic Missile Program,” Behnam Ben Taleblu describes in impressive detail the origins, evolution, and future of a weapon that has become synonymous with the Iranian threat. Taleblu leverages an impressive array of English- and Persian-language sources to produce one of the most comprehensive publicly available assessments to date of Iranian ballistic missile capabilities and intentions. In addition to showing how and why Iran’s ballistic missiles will improve over time, Taleblu explains how Tehran’s technical progress on missiles will drive it to employ these weapons more often. Expect more missile attacks and transfers from Iran, not fewer, he argues.

Taleblu walks readers through the wartime origins of Iran’s ballistic missile program in the 1980s and the web of individuals and companies that helped Tehran build the Middle East’s largest missile arsenal. He then sheds light on the reasons Tehran has invested so heavily in ballistic missiles over the past 40 years and how the arsenal affects Iran’s nuclear quest and security strategy. The report covers missile tests in Iran and transfers to proxies abroad, while providing a systematic overview of every known Iranian ballistic missile as well as how Iran is using its space program as a potential pathway to develop longer-range missiles that could one day target the U.S. homeland.

Despite its detail, this timely report is accessible to non-technical readers and to those who are not subject-matter experts on Iran. At the same time, the report offers technical experts several avenues for further research and analysis. Taleblu’s findings and recommendations will stimulate a productive policy discussion regarding the steps Washington must take to counter the rising Iranian ballistic missile threat.

Vice Admiral (Ret.) James D. Syring

Former Director, U.S. Missile Defense Agency

January 2023

Illustrations by Daniel Ackerman / FDD

Illustrations by Daniel Ackerman / FDD

Executive Summary

Iran’s ballistic missile arsenal is growing in size and quality. It is a threat to U.S. interests and the security of America’s allies in the greater Middle East. Improvements in ballistic missile precision, range, mobility, warhead design, and survivability (including the creation of underground missile depots) imply an increasingly lethal long-range strike capability in the hands of the world’s foremost state sponsor of terrorism.

Iran’s diverse ballistic missile program is an outgrowth of Tehran’s experiences during the Iran-Iraq War, which taught the nascent revolutionary regime the imperatives of deterrence and self-reliance. Status and security considerations also spur Iran’s ballistic missile drive, as they do its nuclear program.

Iran’s ballistic missile program benefits from sustained elite backing. The program was established by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the ideological military that exists alongside Iran’s conventional forces. The missile program is now underwritten by a broad swath of government-connected defense contractors, enabling the procurement, production, and proliferation of missile systems and associated technologies or materials.

Ballistic missiles offer Tehran the means to deter, punish, and coerce adversaries. They compensate for Iran’s conventional warfighting deficiencies and keep the door open for nuclear weapons. According to the 2019 U.S. Missile Defense Review, missiles constitute “one of Tehran’s primary tools of coercion and force projection.”1

Iran’s ballistic missile arsenal also provides Tehran with the confidence and security to pursue its revisionist foreign policy with less fear of military reprisal. This may lead to increased risk-taking, including battlefield use of its arsenal. This was apparent in over half a dozen ballistic missile operations launched from Iranian territory between 2017 and 2022, one of which, in 2020, included strikes on bases in Iraq housing American soldiers. Failure to deter Iran will likely guarantee more missile use. In 2022, for example, Iran launched almost three times as many ballistic missiles as it did in 2021. A missile’s ability to reach its target in minutes amplifies existing challenges in an already troubled region.

Since agreeing to the 2015 nuclear deal, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), Iran has launched at least 228 ballistic missiles, including failed and successful flight tests of surface-to-surface systems in drills and military operations as well as space/satellite launch vehicles (SLV) from its own territory. In addition, Iranian proxies in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen have received ballistic missiles or associated technology from their patron. This weaponry bolsters Iran’s forward-deployed deterrent and threatens U.S. forces in the Central Command (CENTCOM) area of responsibility as well as partners such as Israel and the Arab states of the Persian Gulf.

The JCPOA does not address ballistic missiles, but the deal is slated to remove EU penalties on Iran’s missile brain trust by October 2023. UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 2231, which accompanied the JCPOA, terminates prohibitions on both Iranian missile testing and transfers by the same date. The deal thereby waters down previous UN penalties on Iran’s missile program and inhibits a more coercive Iran policy by Washington and its European partners.2

Iran is unlikely to curb its missile program absent sustained pressure. Even intense pressure may at best impede rather than end Iran’s missile aspirations. Trading away sanctions leverage for concessions of little value, such as a range cap or a mere promise not to produce intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), makes little sense. The resurrection of the JCPOA, or a weakened version of it, will also be unhelpful in this regard. So, too, would attempts to view the missile program purely as an arms control matter, in isolation from Iran’s regional policies.

Western policymakers must reach consensus on how to counter the Iranian missile threat, the utility of any potential missile agreement, the degree to which any such deal can be verified, and how much of a ballistic missile capability can be tolerated in the hands of the world’s foremost state sponsor of terrorism. Absent Western unity and resolve, the regime is certain to best the West at the negotiating table.

Washington should adopt policies that disrupt, deter, devalue, and, when necessary, defang the Iranian missile program through diplomatic, informational, military, and economic means. This report offers several options under each rubric, to include increasing sanctions pressure, the enforcement and broadening of export controls, disrupting procurement and proliferation networks through exposure and interdiction, and increasing regional air and missile defense capabilities.

Birth of the Iranian Ballistic Missile Program

“As I look at the theater and I look at the Iranian threat, that is the most concerning threat to me.” That is how then U.S. CENTCOM Commander General Kenneth F. McKenzie, who was responsible for U.S. forces in the Middle East, answered a question in April 2021 about Iran’s evolving ballistic missile capabilities. “Over the last five to seven years,” he added, “the Iranians have made remarkable qualitative improvements in their ballistic missile force while it has grown quantitatively as well, and now numbers, depending on how you choose to count the weapons, something a little less than 3,000 of various ranges.”3 In an interview that December, General McKenzie went further. A media report paraphrased him as saying Iran’s missile program was now more of an “immediate threat than its nuclear program,” and that missiles provided Tehran with “overmatch” defined as “the ability to overwhelm” the U.S. military or partner forces in the region.4

For years, U.S. directors of national intelligence under both Democratic and Republican administrations have attested that Iran’s ballistic missile arsenal is the largest in the Middle East.5 While analysts have traditionally written off Iran’s conventional military capabilities as lackluster, its ballistic missile program has increasingly drawn the attention of Western policymakers, especially after a January 2020 precision strike used short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs) against bases in Iraq where American forces were located.

Like most of the regime’s military capabilities, its ballistic missile program emerged from two foundational events: the late Shah’s military buildup prior to the 1979 Islamic Revolution and the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War. Yet the impact of the latter drastically outweighs that of the former. In 1977, Tehran reportedly inked an agreement with Israel codenamed “Project Flower” to purchase modified Israeli surface-to-surface missiles (SSMs).6 While the project stopped due to the onset of the Islamic Revolution, it represented Iran’s first attempt to procure an unmanned long-range strike capability. But it would not be the last.

Wartime Origins and Post-War Evolution

At 3:20 a.m. on March 12, 1985, the nascent Islamic Republic of Iran launched its first ballistic missile. Assisted by a team of Libyan missile engineers, Tehran fired a Scud-B at a cement factory near Iraq’s Kirkuk oil refinery.7 The strike marked the first of an estimated 117 Scud missile launches by Iran during the Iran-Iraq War.8 After Iranian population centers and other targets absorbed Iraqi Scud-B and FROG-7 attacks aimed at eroding Tehran’s will to fight, the Islamic Republic had finally “responded in kind.”9

Iran undertook a deliberate and graduated approach when responding to Iraqi missile and rocket attacks, as the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) detailed in a documentary chronicling the evolution of Iran’s missile program and the life of its founder.10 Iran’s first Scud missile launch against Iraq marked a critical juncture in the eight-year war and taught the regime new methods of force employment and how to establish deterrence.

There was an urgent need for such capabilities. Before war erupted in September 1980, the Islamic Republic was both grossly unprepared and distracted.11 Six months after the victory of the Islamic Revolution was declared, the Iranian army and air force encountered significant shortages and personnel issues.12 Iranian revolutionary authorities, which already distrusted the armed forces, inherited a military in disarray.13 The government also slashed Iran’s military budget and purged the officer corps of the national military, or Artesh.14

After Iranian students overran the U.S. embassy in Tehran and took American diplomats hostage in November 1979, Washington froze Iranian government assets, thereby impeding Tehran’s procurement of military systems. In 1983, the United States initiated Operation Staunch, which aimed to deny the Islamic Republic technology for its war effort.15 By 1984, Tehran had earned a U.S. designation as a State Sponsor of Terrorism,16 instituting a complete ban on U.S. arms sales and exports of controlled dual-use goods to Iran.17

Having won few friends abroad since 1979, Iran turned to rogue regimes in Syria and Libya for missiles. Hafez al-Assad’s Syria offered training on Scud systems but refused to transfer weapons.18 More permissive was Muammar al-Qaddafi’s Libya, which provided Iran with a contract for Scuds, transporter-erector launchers (TELs), and a missile engineering team for training.19 The Libyan-supplied Scuds quickly demonstrated the deterrent value of ballistic missiles. After only a few Iranian retaliatory strikes, Iraq’s attacks on Iranian cities stopped.20

However, reportedly due to Tehran’s refusal to fire Scuds at Saudi Arabia — a condition to which Iranian officials had allegedly agreed when negotiating with Libya21 — the Libyans cut off assistance and attempted to sabotage Iran’s remaining stockpile.22 This left the Iranians defenseless against resumed strikes by Iraq. Yet by reverse engineering the Libyan Scuds and procuring components from North Korea, a small team led by newly minted IRGC missile force commander Hassan Tehrani-Moghadam enabled the continued firing of Iran’s limited Scud arsenal. Tehrani-Moghadam’s efforts would earn him the moniker, “father of Iran’s missiles.”23

Iran fired its first Scud without any foreign assistance on January 11, 1987.24 Later that year, Tehran received an estimated 100 Scud missiles from North Korea.25 Many of these Scuds struck population centers during the “war of the cities,”26 as the conflict came to a close in 1988.

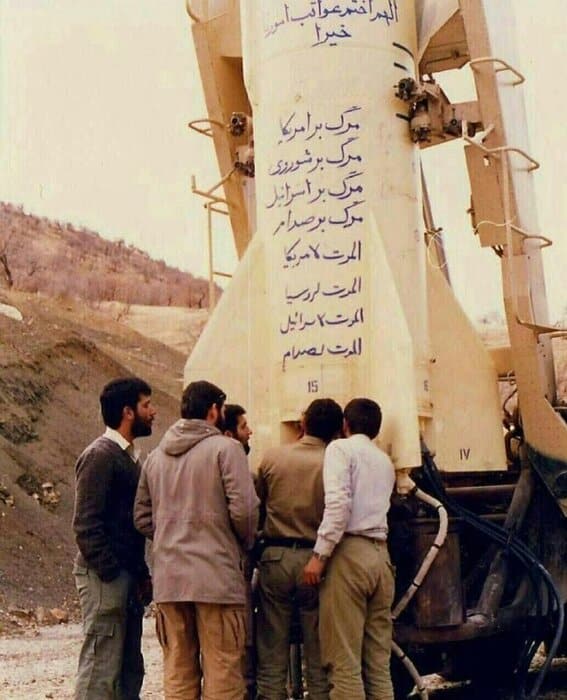

An Iranian Scud missile from the Iran-Iraq War with the following written in both Persian and Arabic, “Death to America, Death to the Soviet Union, Death to Israel,

Death to Saddam.”(Islamic Republic News Agency)

For Tehran, the Iran-Iraq War heightened the imperative of domestic arms production. Iran produced several rocket systems in the 1980s, including an unguided artillery rocket known as Oghab.27 Iran later developed another rocket, named the Nazeat, variants of which remain in service today.28 In the post-war period, experimentation with various forms of rocket propellant gave Tehran the capability to build larger, longer-range, and increasingly more capable solid-propellant systems.29 Iran’s progress on solid-propellant systems has yielded an increasingly precise conventional strike weapon employed in public military operations over the past half decade. Iran has also developed at least two solid-propellant SLV motors, raising questions about its ICBM aspirations.30

Foreign military support also continued into the post-war period.31 China provided at least one whole SSM system, dubbed the Tondar-69,32 as well as gyroscopes and other missile-related technologies.33 Russia also provided technical assistance and raw materials for the Iranian missile program in the 1990s.34 China remains a key jurisdiction for procuring dual-use goods for the regime’s missile program.35

Of all of Iran’s outreach, engagement with North Korea proved the most fruitful. In the early 1990s, North Korea transferred Scud-Cs to Iran, as well as more TELs.36 Over the past four decades, Iran has procured at least three whole ballistic missile systems from North Korea. Pyongyang reportedly developed Iran’s first nuclear-capable medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM), known as the Nodong-A, which Tehran produced under the name Shahab-3 and first tested in the late 1990s. Today, the Shahab-3 is the bedrock of several Iranian liquid-propellant MRBMs and SLVs.37 In the early 2000s, Pyongyang provided Iran yet another liquid-propellant nuclear-capable ballistic missile that may be the foundation for a potential intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) capability.38

The IRGC, which developed Iran’s ballistic missile program, believes that had Tehran abandoned its missile and long-range strike ambitions when the war ended in 1988, another devastating conflict would have taken place.39 This unwavering belief in the deterrent power of missiles has driven Iran’s procurement and production of missiles into the current era.

America’s response to Tehran’s missile advancements has largely been a policy of denial and containment: a mix of sanctions, export controls, diplomatic pressure, and missile defense initiatives. Furthermore, Washington has narrowly regarded ballistic missiles as nuclear delivery vehicles rather than as conventional-strike assets. To keep pace with the evolving Iranian ballistic missile threat, the United States must refine and enhance these policies.

The Role of Ballistic Missiles in Iran’s National Security Strategy

The pursuit of status and security drive Iran’s ballistic missile program just as they do its nuclear program.40 Ballistic missiles feature prominently in Iranian national security strategy, offering a political, military, and even psychological tool to deter, punish, and coerce Iran’s adversaries, as well as to support Tehran’s interconnected foreign, security, and defense policies.41 While the overarching goal of Iran’s national security strategy is the perpetuation of the regime,42 other aims include regional primacy and self-reliance.43

Status and Security: Two Sides of the Same Coin

In 2018, the Office of Iran’s Supreme Leader produced a video featuring wreckage from Iraqi missile attacks on Iranian cities during the Iran-Iraq War. “Do you remember?” Khamenei asked. “We had no missiles, we had nothing to defend with, we were forced to put our hands together and watch.”44 The video ended with a montage of Iranian ballistic missile launches. The message was clear: Iran’s ballistic missile arsenal and capabilities are among the Islamic Republic’s most identifiable achievements.

The regime deems these weapons to be crucial to its existence, its revolutionary foreign policy, and increasingly, the capabilities of its proxies. According to former IRGC Commander Mohsen Rezaie, “Our missiles were planted like a sapling in the war. We harvested its first fruits during the war. But the main fruits of this tree took place after the war, in a manner that Iran’s missile capabilities in the region are unique.”45

Today, Iran’s ballistic missile arsenal contains an array of short- and medium-range systems. Iranian officials are proud of their newfound status as the region’s preeminent missile power and use that status to press for hegemony. Iranian officials and media outlets tout foreign coverage of Iran’s missile developments as a measure of the regime’s prowess.46

As much as it shuns the current global order, Tehran covets international recognition of its scientific, technical, and military advances. In fact, Iranian officials boast of the regime’s missile and military progress while under sanctions and believe it is a model for other states to employ.47 They also frame opposition to Iran’s missile and military advances as hostility to the regime. IRGC Aerospace Force (IRGC-AF) Commander Amir-Ali Hajizadeh neatly captured this view when he said, “Now they have made the missile issue an excuse… They seek to do something so that we are disarmed and so that we cannot respond in kind.”48 Similarly, Gholamhossein Gheibparvar, former commander of the Basij paramilitary force, said, “The issue of Westerners is not over missiles; rather, their issue is about Islam and the Revolution.”49

Strategies and Capabilities Enabled by Iran’s Ballistic Missiles

Iranian strategy prioritizes above all else the ability to deter or punish attacks on the homeland and, when possible, on regime interests abroad. Some Iranian officials believe that Western hostility toward Tehran’s ballistic missile program stems from the high deterrent value of Iran’s domestically produced missiles, which — in their view — severely complicate military plans targeting Iran.50 As Michael Eisenstadt notes, ballistic missiles have become “central to Iran’s ‘way of war’” and are one leg of “Iran’s deterrence triad,” which also includes asymmetric maritime capabilities and employment of terrorist groups as proxies.51

During the Iran-Iraq War, Iran sought to deter Iraq by “responding in kind.” Early in the “War of the Cities,”52 Iran’s ballistic missiles permitted the regime to punish its Iraqi adversary and to obtain pauses in warfighting.53 Near the end of the conflict, however, as Baghdad’s missile capabilities improved and Tehran fell within range of Iraqi Scuds, Iranian officials saw the devastating impact these projectiles had on Iran’s population. Wartime morale dropped significantly, and citizens fled the capital.54 This had an enduring psychological effect on Iranian leaders.55

Today, Iranian officials use the example of the eight-year war to illustrate the cost aggressors would pay in a conflict56 and believe several wars have already been prevented as a result.57 They also believe the war was the source of the regime’s deterrent and defensive capabilities.58 As Kenneth Pollack notes, after the war, Iranians armed themselves not against renewed Iraqi aggression, but against a far more powerful adversary: America.59 Tehran has focused on how best to contest American military dominance and deter a U.S. attack while advancing its revolutionary foreign policy.60 Iranian military officials assert that the regime’s strength and deterrence power has robbed adversaries, including the United States, of the will to fight,61 enabling Iran to pursue its regional ambitions with greater ease.

Such thinking assumes that as the regime conducts its regional policy — exporting its ideology and creating, co-opting, and supporting local armed groups62 — Iran will need tools to offset conventionally superior adversaries who have a vested interest in maintaining the regional order that Iran seeks to overturn.63 To adapt an analogy developed by Karim Sadjadpour,64 ballistic missiles provide Tehran with a shield with which to deter attacks, while Iran-backed proxies and militia groups function like a sword that thrusts ahead, operating mostly below the threshold that would prompt Tehran’s adversaries to use military force. Thus, Iran’s ballistic missiles devalue its adversaries’ most powerful tool: conventional military force.

To bolster deterrence, Tehran wields a mix of incendiary rhetoric, parades, and media to trumpet its ballistic missile capabilities. Flight tests, transfers, and battlefield-use of missiles also help reinforce deterrence, based on Tehran’s understanding of its adversaries’ “image of war”65 and risk tolerance. By signaling that a potential conflict with Iran will involve ballistic missiles, making it protracted, costly, and bloody, the Islamic Republic seeks to force adversaries into a policy of begrudging accommodation.

Iran’s ballistic missile arsenal continues to improve in terms of both quantity (the size and diversity of the force) and quality (missile precision and ability to carry submunition payloads or maneuvering warheads). These improvements may embolden Tehran to take more risks, as demonstrated by a January 2020 barrage against U.S. positions in Iraq. Scholars believe that the increasing precision of Iran’s missile forces may lead it to adopt a more offensive military doctrine over time.66 Combined with Iranian perceptions of U.S. irresolution and risk aversion, an enhanced arsenal may lead to a lower threshold for the use of ballistic missiles.67

Ballistic missiles offer the regime both a conventional and an unconventional long-range strike capability that fits into a broader spectrum of unmanned aerial threats. This spectrum includes mortars, conventional artillery, rockets, drones, and both cruise and ballistic missiles. Tehran treats ballistic missiles as its strongest vehicle to deliver punishment and thus a replacement for an effective air force, which the regime lacks because of sanctions that block access to spare parts and (until recently) conventional arms markets.68 Compared to advanced fighter aircraft, ballistic missiles require significantly less infrastructure to launch and cost considerably less to develop and maintain. While fighter aircraft may offer more diverse striking options given the array of weapons they can carry (not to mention their reusability), ballistic missiles offer speed and surprise. Moreover, the comparatively high velocity of a ballistic missile makes it harder to intercept than a fighter jet.

The lapse of the UN arms embargo on Iran in October 2020 removed a significant barrier inhibiting Iran’s missile programs. Although UNSCR 2231 continues to ban exports to Iran of Category I and II missiles and other items controlled under the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR)69 until October 2023, the arms embargo’s lapse marked the beginning of an unencumbered advance toward modernizing Iranian forces. This will not lead Tehran to replace its ballistic missiles with fighter aircraft, nor will Tehran build formidable conventional forces in the short-to-medium term. But coupled with the revocation of UN missile prohibitions in 2023, the arms embargo’s lapse will enable Tehran to improve its military, rocket, and missile programs gradually. Iran’s missile advances will force its adversaries to continue investing in more expensive air and missile defenses, a fact the IRGC appears to grasp and is intent on exploiting.70 Given Iran’s unique experience in the Iran-Iraq War, ballistic missiles are certain to remain central to Iran’s national security strategy.

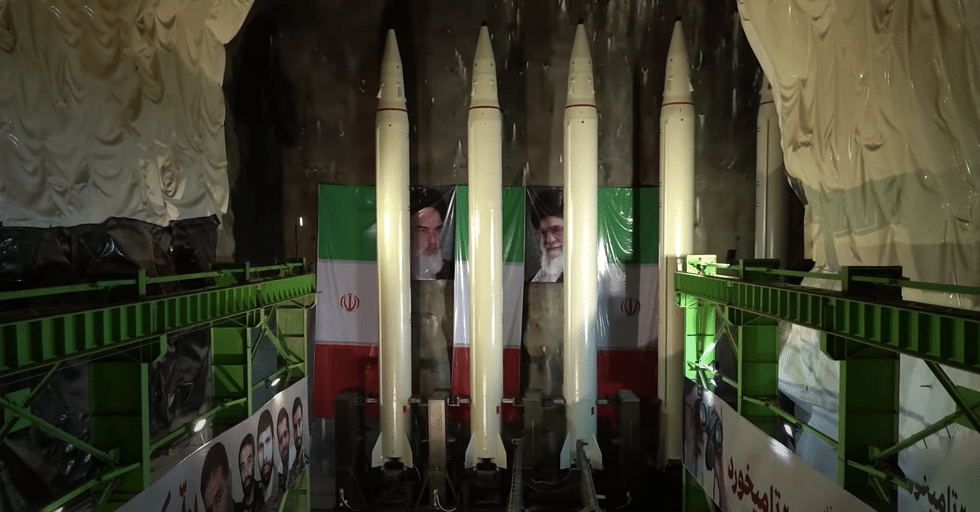

A subterranean Iranian SRBM assembly line with a poster (left) quoting Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei as saying,

“Our enmity with America is eternal.” (Young Journalists Club)

Delivery Vehicle for Potential WMD Capabilities

During the war, the need to deter and punish Iraq’s leadership led the nascent Islamic Republic to develop both ballistic missiles and weapons of mass destruction (WMDs), specifically chemical weapons. U.S. intelligence has documented how Iran’s perceived need to respond to Iraq’s widespread use of chemical agents during the Iran-Iraq War led Tehran to employ this WMD despite earlier “moral and possibly religious” prohibitions the regime harbored. According to the CIA, “in April 1987, Iran clearly crossed the chemical barrier.”71 There may come a day when Tehran opts to cross the nuclear barrier, too.

According to other U.S. intelligence reports, “Iran’s ballistic missiles are inherently capable of delivering WMD.” Should the regime ever develop nuclear weapons, “it would choose a ballistic missile as its preferred method of delivering” them.72 A nuclear weapons program has three main requirements: fissile material (i.e., weapons-grade uranium or reprocessed plutonium), weaponization (i.e., warhead development),73 and a delivery vehicle. Iran has clearly worked on all three. Several classes of Iran’s ballistic missiles already surpass the MTCR range and payload thresholds for nuclear-capable systems.74 Continual refinement of this arsenal through flight-testing, re-entry vehicle (RV) design, and other improvements makes Tehran less likely to face delays related to having a functional delivery vehicle.75 According to the late Michael Elleman, Iran is “the only country to have developed” a 2,000-kilometer-range missile without “first having developed nuclear weapons.”76

Evidence from Tehran’s atomic archive — a trove of nuclear documents Israel seized in 2018 — that pertains to Iran’s crash program for a bomb known as the AMAD plan77 indicates a link between Iran’s missiles and quest for a nuclear weapon.78 Several International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) reports describing components of the AMAD plan specifically mention Iran’s Shahab-3 MRBM. Notably, a May 2008 IAEA report mentions correspondence between an Iranian military contractor specializing in liquid-propellant missiles (the Shahid Hemmat Industrial Group, or SHIG) and Iran’s top military-nuclear scientist at the time, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh.79 The IAEA report also notes that Iran conducted studies involving “the testing of at least one full scale hemispherical, converging, explosively driven shock system that could be applicable to an implosion-type nuclear device.” 80

The AMAD plan, Fakhrizadeh, and a project to redesign the Shahab-3 were also mentioned in the annex of a November 2011 IAEA report, which observed “a link between nuclear material and a new payload development programme.” The report also revealed that Tehran had “conducted computer modelling studies of at least 14 progressive design iterations of the payload chamber and its contents to examine how they would stand up to the various stresses that would be encountered on being launched and travelling on a ballistic trajectory to a target.”81

While a 2015 IAEA report on the possible military dimensions (PMD) of Iran’s nuclear program noted that Tehran conducted nuclear weapons-related activities “prior to the end of 2003 as a coordinated effort, and that some activities took place after 2003,”82 the report failed to address the evolution of Iran’s nuclear weapons efforts. Fakhrizadeh continued to be involved in nuclear-related entities that evolved into the Organization of Defensive Innovation and Research (SPND).83 SPND retained AMAD plan staff and expertise as a hedging strategy with overt and covert components.84 While Fakhrizadeh was assassinated in late 2020, there is no indication that his death ended Tehran’s nuclear aspirations. Iran’s latest nuclear moves have given the regime irreversible nuclear knowledge that helps put it in striking distance of a potential nuclear weapons threshold capability.85

Given Iran’s threat perceptions, revolutionary foreign policy, and obsession with deterrence, acquiring nuclear weapons would be a logical step. It is no accident that Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs draw from the same wellspring of experience: the Iran-Iraq War.86 Tehran’s desire to keep its nuclear options open also explains why the regime was willing to endure significant sanctions pressure. Iran consented to the JCPOA specifically because it did not permanently block Tehran’s path to the bomb.

Attaining a nuclear weapons capability would likely foster a sense of invincibility in an already revolutionary regime and could, in turn, lead to more regional conflict. Given the speed that ballistic missiles travel, prudence dictates that if Iran developed a nuclear weapons capability, the region would have to go on high alert each time the Islamic Republic flight-tested or employed ballistic missiles in military operations.

Iran’s Missiles in Action

Aside from parading ballistic missiles to herald a new system or capability, Iran has three primary means of missile employment: tests, transfers, and military use during peacetime. These actions offer three unique levels of analysis to view Iran’s capabilities and intentions.

Tests and Drills

To reap strategic dividends from ballistic missiles as a deterrent, as a substitute for airpower, and as a potential nuclear delivery vehicle, Tehran must ensure these weapons are functional. Continuous flight testing and military drills help accomplish this. A delay in testing leads to foreign inferences about the reliability of older systems, the performance of newer ones, budgetary considerations, or even political restraint. However, a failed test — that is, an inability to launch or an explosion mid-air — can be as much a learning opportunity as a political or technical setback. According to IRGC-AF commander Hajizadeh, Iran guards against missile failure during drills by employing several missiles against a single target.87 Tests in which Iran fires multiple missiles also offer insight into potential Iranian operations, such as saturation attacks.

At the most basic level, flight testing provides critical data about the readiness, reliability, precision, destructive capacity, and overall performance of a missile. It also speaks to the proficiency of missile crews, which may be called upon to erect and launch these projectiles at any time.

Launches can also serve as a signal of resolve against sanctions or international prohibitions on the regime’s ballistic missile activities, such as UNSCR 2231. In recent years, Iranian officials have grown more attuned to the political impact of launches. In February 2016, Hajizadeh alluded to the interest of foreign intelligence services in Iran’s missile testing, noting, “Every time we launch a missile, their spy planes begin working.”88

Unlike wind-tunnel tests, outdoor engine tests, and laboratory simulations, flight-testing a complete missile system is the most public trial the regime can undertake short of an actual operation. It is therefore the most controversial. In April 2015, former IRGC Commander and current Vice President for Economic Affairs Mohsen Rezaei revealed:

It is 10 years that we are engaging in missile drills, but in the last two years, in cooperation with the government, our brothers in the IRGC have not been publicizing their drills so that our friends in the current of nuclear negotiations have the opportunity for discussions… drills are a kind of operation, when we commence drills it causes those who think about threatening Iran to back down and realize that today is not yesterday. Also, by holding missile drills, the readiness of our missile forces increases, and we will be able to test our missiles.89

Iran’s cognizance of the political implications of public testing peaked in 2017, when Hajizadeh reprimanded Iranian authorities for removing an SLV from a launchpad due to concerns over what the Trump administration might do in response.90

The target or type of missile fired may carry significance.91 All of Iran’s MRBMs, for instance, surpass the MTCR threshold qualifying them as nuclear-capable platforms. As such, Iranian MRBM testing may be an effort to refine a nuclear delivery vehicle. After an MRBM drill in March 2016, Hajizadeh re-upped the claim that Iran had missiles with a range of up to 2,000 kilometers specifically for the purpose of striking Israel.92

However, political signaling has its limits. In a 2017 televised debate, then President Hassan Rouhani, seeking a second term, slammed the IRGC for missile launches in 2016 featuring genocidal slogans against Israel. “They wrote slogans on the missiles so that the JCPOA could be disrupted,” Rouhani said.93 Though the former Iranian president has since offered praise for the missile program,94 his critique is instructive, as it sheds light on how missile testing and the missile program more generally may be tools to adjudicate domestic or factional debates. Tehran University political scientist Sadegh Zibakalam similarly cited Iran’s missile launches as a tool used by ultra-hardliners to weaken the JCPOA and its domestic proponents.95

While it is not always clear whether a given missile test was pre-planned or conducted in response to events, one thing is certain: Ballistic missile launches are a key tool of both political and military communication for the Islamic Republic.

Since agreeing to the JCPOA in July 2015 through December 2022, Iran appears to have launched at least 228 ballistic missiles, averaging over 32 missiles per year.96 This figure includes failed and successful flight tests, drills, and military operations launched from Iranian territory. It also includes SLV tests but excludes non-SSMs with a ballistic trajectory. Beginning in mid-2018, Iranian media reduced their coverage of missile tests, covering only military operations and drills. This has rendered assessments that do not rely on satellite imagery or official non-Iranian reporting (such as from the U.S. or UN) hard to make. Relatedly, there is no publicly available (or known) U.S. government tally to date of these launches. Appendix A contains a detailed list of all reported launches employing the criteria stated above.

The 228 launches include at least 91 close-range ballistic missiles (CRBMs), 84 SRBMs, 36 MRBMs, 16 SLVs, and one fully unknown platform. Both Iran’s post-JCPOA CRBM and SRBM launches almost tripled its MRBM launches, reflecting a drive to develop more precise, shorter-range systems and to employ these projectiles in military operations. The recent rise in SLV launches should also be noted. The spikes in 2018, 2020, and 2022 reflect military operations against targets in Iraq and Syria, while multiple military drills in 2021 explain the spike seen that year.

Transfers

Transferring ballistic missiles or related components, technologies, or capabilities to proxies and partners is another way Tehran uses missiles to support its broader policy goals. The Islamic Republic has been proliferating missiles for over two decades. In 1999, Tehran reportedly inked an agreement with the Democratic Republic of Congo for transfers of modified Iranian Scud missiles.97 Around the same time, Iran also began to share MRBM production technology with Libya,98 the country that furnished Tehran with its first Scuds during the Iran-Iraq War.99 The 2020 removal of Iran’s UN arms embargo, which covered both exports and imports, may permit the Islamic Republic to ramp up its proliferation of missiles and military technology.

Alarmingly, the regime does not simply export missiles or missile-related technologies. It is now also an exporter of missile production capabilities. Iranian officials have increasingly highlighted these transfers in their commentary. In 2014, Hajizadeh bragged that the Iranians “learned how to employ [missiles] from [Syria], but we taught [the Syrians] how to produce [missiles]. The factories for the production of the Syrian missile industry have been transferred from Iran to [Syria].”100 In January 2021, Hajizadeh again boasted, “Gaza and Lebanon are on the frontlines of this conflict, and whatever you see in terms of missile capability in Gaza and Lebanon has taken place with the support of the Islamic Republic of Iran.”101 These transfers advance three objectives:

- Growing the conventional strike capabilities of the “Axis of Resistance.” Enhancing the strike capabilities of the Axis of Resistance, a term used by Iranian officials to describe their network of proxies and partners, offers Iran two benefits. First, more lethal systems increase the effectiveness of Iran’s proxies in local battles against shared adversaries. Second, the greater the quality and quantity of Iranian proxies’ missiles and rockets, the stronger Tehran’s conventional deterrent. A more lethal capability in the hands of these proxies functions as a knife against the neck of U.S. partners in the region aimed at complicating policy planning and eroding both the will and capability to respond to any instance of Iranian aggression.

As John Hannah observes, Tehran’s investment in the conventional military capabilities of its proxies transforms the Israel-Lebanon border into an Iranian version of the situation along the 38th parallel between North and South Korea. Much as Pyongyang uses its ability to bombard Seoul with overwhelming conventional force to deter preemptive attacks on its homeland and nuclear infrastructure, the Islamic Republic arms Lebanon’s Hezbollah to help deter a potential Israeli strike against Iran102 and increase the costs of action against Hezbollah itself. - Cementing political gains through military means. Iran’s material support to terror groups is not just consistent with the regime’s desire to export its Islamic Revolution. It is also aimed at maintaining its partners’ loyalty in a changing Middle East.

- Developing and testing an arsenal in exile. The wide geographic dispersal of Iranian ballistic missiles and missile-related technology renders inadequate air and missile defenses trained only on launches from Iranian territory. By proliferating missiles and rockets, Iran can assess their performance under battlefield conditions without the risks of a conflict on Iranian soil. The Islamic Republic’s support for its regional proxies may also be leading to the development of systems absent from Tehran’s own arsenal.103 Often described by Iranian officials and their proxies as indigenously developed weapons, these new systems make Tehran’s role less visible and insulate the regime from blowback.104

There are four jurisdictions today where Iranian ballistic missile-related transfers have impacted the regional balance. They are Yemen, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq. (See Table 1.) Unsurprisingly, these are the same jurisdictions that an Iranian parliamentarian boasted about controlling in 2014: “Currently, four Arab capitals are in the hands of Iran and are dependent on the Islamic Republic of Iran.”105

Table 1: Iranian Ballistic Missile Proliferation in the Middle East

| Proxy/Partner Name; Jurisdiction | Ballistic Missile(s)/Capability Transferred | Target(s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Houthis (a.k.a. Ansar Allah); Yemen | Modified Scud variant: Burkan-1106 and modified Qiam-1 variants: Burkan-2H,107 Burkan-3/Zolfaghar.108 More recently, the Hatem (assumed Kheybar Shekan), Karrar (assumed Fateh-110 or Fateh variant), and Falaq (assumed Qiam-2) | Saudi Arabia, UAE,109 potentially Israel in the future110 | Iran likely supported upgrades to the Badr rocket,111 which is still in use as a precision-guided munition (PGM) called the Badr-1P or Badr-F |

| Assad regime; Syria | Fateh-110,112 missile factories113 | Syrian rebels, potentially Israel | Syria has begun producing Fateh-110s under the name M600 and transferring them to Hezbollah.114 |

| Hezbollah; Lebanon | Fateh-110,115 PGM kits,116 subterranean missile factories117 | Assumedly Israel | As of this writing, Hezbollah has not fired ballistic missiles at Israel. |

| Shiite militia groups118 (e.g. Kataib Hezbollah); Iraq | Fateh-110, Zulfiqar. No known transfer to militia groups in Syria directly from Iran. | Assumedly Israel or U.S. and coalition forces in Iraq | As of this writing, neither Kataib Hezbollah nor any other Iran-backed group in Iraq has used ballistic missiles against U.S. or Israeli forces.119 However, rocket attacks against U.S. forces continue. |

Although Iran has supplied the Palestinian terror groups Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) with Fajr-3 and Fajr-5 rockets,120 those systems are unguided and thus excluded from this analysis. At the time of this writing, Iran is not believed to have supplied those groups with entire ballistic missiles.121 According to Hajizadeh, “Palestinians have become self-sufficient in many areas… [I]t is true that they have learned from Iran, we will definitely help any group, any country, that wants to stand against the Zionist regime.”122 Should Tehran supply Palestinian terror groups with precision-strike capabilities, it would be consistent with the regime’s evolving approach to weapons proliferation and technology diffusion for its proxies.

The Houthis

In Yemen, where it supports the Houthi rebels against a Saudi-led coalition, Iran has seen the greatest return on its investment in missile proliferation and related technology transfers. Having captured Scud and Tochka SRBMs from the ousted Yemeni government,123 the Houthis also developed rocket capabilities. While coalition airpower targeted those capabilities early in the conflict, Iranian military assistance has apparently more than compensated for the loss.

Iranian missile transfers have helped grow Houthi long-range strike capabilities, putting civilian population centers at risk, including the Saudi capital, Riyadh.124 This has eroded the prospect of a Saudi victory at little cost to Tehran. More broadly, Iran’s support to the Houthis offers the Islamic Republic an opportunity to establish a foothold on the Arabian Peninsula and Red Sea,125 bleed its Saudi rival, and contest U.S. economic pressure.

Starting in 2016, the Houthis unveiled and have employed the Burkan-1 SRBM, a Scud variant.126 Though Tehran’s connection to the Burkan-1 remains unproven given the presence of Scuds in Yemen before the war, Iranian support for its redesign would be consistent with its overall strategy. In 2017, the Houthis debuted the Burkan-2H, which featured more telltale signs of Iranian assistance. For example, jet vanes on debris from the system bore markings used by Iranian defense manufacturers.

In addition, the Burkan-2H shares several identifiers with Iran’s Qiam-1 SRBM, which is a Scud-C variant. Like the Qiam-1, the Burkan-2H is a finless, single-stage, liquid-propelled Scud variant topped with a triconic, or “baby bottle,” warhead. The UN Panel of Experts on Yemen assessed in January 2018 that Burkan-2H is “an advanced derivative of the Qiam-1.” The panel also suggested that “most likely,” Burkan-2H components were trafficked overland from Oman after smaller “ship to shore transfers.”127 Photos of the Burkan-2H contain evidence of shoddy welding, vindicating the thesis of local reassembly of larger imported components.128

In mid-2018, Washington sanctioned five Iranians for supporting the Houthi missile program. Among them were individuals with ties to the IRGC Quds Force (IRGC-QF), which supports Iranian external operations; the IRGC-AF’s Al-Ghadir Missile Command, which has operational control over Iran’s missile arsenal; and the IRGC’s Research and Self-Sufficiency Jihad Organization (IRGC-RSSJO), which supports Iranian missile research and development.129

In 2019, the Houthis launched their first MRBM, the Burkan-3, at targets in eastern Saudi Arabia.130 This extended-range Burkan, which would reappear in 2021 as the Zolfaghar,131 carries a narrower conical warhead than most Iranian MRBMs but has the same tail-section fins at the Qiam family. The Houthis are the only Iranian partner to have received or developed MRBM capabilities. In conjunction with drones and cruise missiles, Houthi Zolfaghar use has broadened beyond Saudi Arabia with attempts to target critical infrastructure132 and even a U.S. base in the UAE in early 2022.133

Iran is believed to be behind the move towards precision-guided weapons in Yemen. Starting in 2018, the Houthis unveiled the Badr-1P, the guided version of an older artillery rocket that has since been modified134 and used in various missions, including against attacks on civilian targets like Aden International Airport in December 2020.135 The Houthis also possess a host of upgraded shorter-range systems, such as the Qasim and larger Qasim-2, which the Houthis unveiled in an arms exhibition in 2021.136 Many of these new systems share design similarities with solid-propellant Iranian SRBMs of the Fateh-110 family, like control fins under the warhead and at the aft section of the missile. These similarities lend credence to the theory of local production with Iranian technical assistance. Cementing that theory are three new SSMs — the Hatem, the Karrar, and the Falaq — revealed at a September 2022 military parade in Sana’a commemorating the eighth anniversary of the Houthi takeover of Yemen. These SSMs appear to be carbon copies of Iranian ballistic missiles with precision-strike capabilities.137

The Assad Regime and Lebanese Hezbollah

In the Levant, Iran’s missile support for the Assad regime in Syria and for Hezbollah in Lebanon is inextricably linked. In 2014, the IRGC-AF’s deputy commander, Seyyed Majid Mousavi, described Syria as a “good bridge” for Iran’s proxies in the Levant.138 Iranian proxies routinely travel across this land bridge, and Tehran uses it to proliferate arms.139 Given the proximity of Syria and Lebanon, the Islamic Republic has looked to the Assad regime to facilitate Iranian support for Hezbollah, including technology transfers when needed, as was the case with the Fateh-110 SRBM, which both Syria and Hezbollah now possess. The Assad regime has reportedly used the Fateh against Syrian rebel groups, but Hezbollah has apparently not employed the missile in combat. IRGC-AF Deputy Commander Mousavi confirmed that the missile capabilities of the “Axis of Resistance” include “the Fateh class of missiles,” enabling Tehran’s proxies to strike all of Israel.140

Hezbollah claims it fired 8,000 rockets at Israel during the 2006 Lebanon War141 out of an estimated arsenal of 13,000.142 In 2010, Israeli military officials estimated that Hezbollah possessed about 40,000 rockets and mortars.143 Recent estimates vary significantly, putting Hezbollah’s arsenal at anywhere from 100,000 to 150,000 rockets and missiles. Meanwhile, Tehran is working to help Hezbollah convert rockets, including Iranian-provided Falaq and Zelzal rockets,144 into precision-guided munitions (PGMs).145 As of February 2021, Israeli intelligence reportedly believed that Hezbollah possessed “a few dozen PGMs.”146 Others believe this number is now in the hundreds.

The Islamic Republic’s evolving missile support for Hezbollah resembles China’s support for Iran’s missile program in the early 1990s, when Beijing reportedly ceased transferring whole systems but continued transferring technology.147 This speaks to Iranian adaptability in response to external pressure and the local needs of Tehran’s proxies.148 Iran’s evolving proliferation patterns can also be seen in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) airstrikes against varying targets related to Tehran’s PGM project.149

The IDF has identified three phases in Iran’s PGM project. During phase one, from 2013 to 2015, Tehran transferred whole systems to Hezbollah. Phase two, from 2016 to 2018, included the trafficking of select components for PGM kits, such as navigation systems.150 Phase three, which began in 2019 and is ongoing, involves efforts to develop PGMs entirely in Lebanon.151 In 2020, the IDF released pictures of factories in Lebanon engaging in this process.152 As Mousavi stated, “Instead of us giving them a fishing hook, from the beginning, the idea was that we must teach them fishing and construction capabilities.”153

Should Iran’s PGM project continue unimpeded, writes Jonathan Schanzer, the Israeli Iron Dome defense system’s “total dominance may come to an end.”154 Uzi Rubin notes that in the era of PGMs, Iron Dome and other forms of “active defense” will be “necessary but insufficient.” Rubin believes that through a combination of precision and sheer volume, Hezbollah’s arsenal could spell trouble for Israeli defenses, as the terror group could mix PGMs into a volley of rocket fire, hoping Iron Dome will prioritize the lesser threats from unguided projectiles.155 Increasingly, Iranian officials are wagering that PGMs will render Israel unable to win a war with Hezbollah.156 Overall, the more precise such projectiles, the less restraint Iran and its proxies may feel against Israel or in the service of Tehran’s regional vision.

Shiite Militia Groups (SMGs) in Iraq

In August 2018, press reports claimed that Tehran had proliferated Fateh-110 and Zulfiqar solid-propellant SRBMs to proxies in Iraq, along with several launchers.157 The Islamic Republic uses Iraq for strategic depth, moving select munitions into Iraqi territory to increase their range and mask Iran’s hand in their potential use. In 2021, for example, Iran-backed militias in Iraq launched drones at Saudi Arabia.158

The SRBM transfers also provide Iraqi militias with an opportunity to train on new systems. Reuters reported that unnamed Iranian officials said the transfers were part of a project to develop missiles for militias.159 The report further noted the presence of missile factories in at least two different parts of Iraq. In December 2019, The New York Times confirmed the SRBM transfers had taken place,160 and were intended to augment the unguided rocket and mortar capabilities of Shiite militias in Iraq. Improving the military capabilities of Iran-backed militias such as Kataib Hezbollah could also lead to political gains for these groups.161

Other Areas?

There is concern that a combination of diminishing international restrictions and increasing missile capabilities and risk tolerance will encourage Iranian ballistic missile proliferation to jurisdictions outside the Middle East. In mid-October, The Washington Post reported Iran would send additional drones to Russia for use against Ukraine as well as ballistic missiles to include SRBMs like the Fateh-110 and the Zulfiqar.162 Reportedly, the Russians sought their improved accuracy.163 The transfer would mark the most significant missile transfer by Iran onto European soil and the second instance of Iranian conventional weapons proliferation to Russia. As of December 2022, no such transfer has been reported.164

Battlefield Use

“I am Iran’s guardian,”165 read a large billboard in Tehran’s Vali Asr Square after Iranian ballistic missile strikes against ISIS in Syria in 2017.166 Accompanying the text was the image of a man wearing an IRGC uniform, with missiles being launched from his hand. After a near two-decade lull, the Islamic Republic had openly fired ballistic missiles from its own territory at an adversary.

Aforementioned IRGC missile launch billboard in Tehran (Twitter/هواداران پرسپولیس)

As of December 2022, Iran has conducted at least 13 ballistic missile operations from its territory since the end of the Iran-Iraq War.167 In the first five (which occurred between 1994 and 2001), Iran fired Scuds at the Mujahideen-e Khalq (MEK), an Iranian dissident organization in Iraq, in retaliation for alleged MEK attacks.168 How much publicity the regime wished to shed on those strikes remains unknown. The next eight strikes (which occurred between 2017 and 2022) featured more precise, shorter-range, and domestically produced systems targeting ISIS terrorists in Syria, Kurdish opposition groups in Iraq, U.S. forces in Iraq, and other Kurdish civilian targets in northern Iraq. Iran described most, if not all, of these strikes as retaliatory.

Table 2: Iranian Military Operations Featuring Ballistic Missiles Since the Iran-Iraq War169

| Date | Codename | Target | Apparent Rationale | Missiles Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| November 1994170 | N/A | MEK base in Iraq | Retaliation for MEK attacks171 | Three Shahabs (likely Shahab-1s or Shahab-2s) |

| November 1994172 | N/A | MEK base in Iraq | Retaliation for MEK attacks173 | Three Scuds (likely Shahab-1s or Shahab-2s) |

| June 1999174 | N/A | MEK base in Iraq | Unclear; likely retaliation for MEK assassination175 | Scud-B (assumed) |

| November 1999176 | N/A | MEK base in Iraq | Unclear; likely retaliation for MEK assassination177 | Scuds (assumed) |

| April 2001178 | N/A | MEK bases in Iraq (at least 3 different locations) | Unclear | 44 to 77 Scuds (likely Shahab-1s or Shahab-2s)179 |

| June 2017 | Operation Laylat al-Qadr180 | ISIS targets in Deir ez-Zour, eastern Syria | Retaliation for ISIS terror attack on Iranian parliament and Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s shrine | Six SRBMs (Zulfiqars and Qiam-1s) |

| September 2018181 | N/A | Kurdish opposition parties in Iraqi Kurdistan | Uptick in tensions between Tehran and Kurdish insurgent groups182 | Seven SRBMs (Fateh-110Bs)183 and drones |

| October 2018 | Operation Zarbat al-Moharram184 | ISIS targets in eastern Syrian city of Hajin | Retaliation for ISIS terror attack in Ahvaz185 | Six SRBMs (Zulfiqar and modified Qiams)186 |

| January 2020 | Operation Shahid Soleimani187 | Bases in Ain al-Asad and Erbil housing U.S. forces | Retaliation for U.S. killing of IRGC-QF chief Qassem Soleimani and Iraqi militia leader Abu-Mahdi al-Muhandis | 16 SRBMs (Fateh-313 and modified Qiams)188 |

| March 2022 | N/A | Alleged Israeli presence in Iraq; home of a Kurdish oil tycoon | Retaliation for alleged Israeli attack from Iraqi soil | 10 SRBMs (Fateh-110)189 |

| September 2022 | N/A (assumed Rabi’a 1) | Iraqi Kurdistan; targets affiliated with Kurdish-Iranian opposition groups | Allegedly responding to Kurdish support for protests | 73 SSMs reported. Assumed solid-propellant due to size and plume color.190 Later revealed as Fath-360 CRBM.191 |

| November 2022192 | Operation Rabi’a 2 | Iraqi Kurdistan | Allegedly responding to Kurdish support for protests | Pictures show at least 12 canisters on TELs. Assumed Fath-360 CRBM. |

| November 2022193 | Operation Rabi’a 2 | Iraqi Kurdistan | Allegedly responding to Kurdish support for protests | No clear number of projectiles fired. Assumed at least 1 Fath-360 CRBM. |

Iranian ballistic missile strike on Al-Asad base in Iraq, January 8, 2020. (Stripes via U.S. Central Command)

Iran’s missile operations are proof that Tehran possesses the ability to punish adversaries using its most prized weapons as well as the commensurate will to overtly launch these weapons from Iranian territory at enemy targets. This willingness contrasts with other covert elements of Tehran’s security policy. Moreover, Tehran may be conducting more missile strikes because it understands American trepidation over Iran’s growing missile force, a point Khamenei underscored while meeting with IRGC commanders after the 2017 Iranian missile strike in Syria.194 While the strikes from 2017 onward were made possible by Iran’s increasingly precise shorter-range missiles,195 they were also enabled by the availability of un-defended targets, meaning the regime has yet to employ its most precise ballistic missiles directly against top-tier missile defense assets.196

Collectively, recent Iranian ballistic missile operations offer at least five lessons:

- Tehran stresses the primacy of deterrence by punishment. As Khamenei stated in 2018, “The enemy knows that if they hit one, they will receive 10.”197 The Islamic Republic frames missile strikes as punishment that any potential aggressor would incur. It also helps to refine a message Iranian leaders conveyed for at least two decades: There is no limited war option with Iran. Khamenei has threatened this by saying, “the era of hit and run is over… your leg will become stuck and we will pursue [you].”198 In January 2020, when officials promised a “hard revenge” for the killing of IRGC-QF chief Qassem Soleimani,199 their weapon of choice was ballistic missiles.200

- Iran’s framing of retaliation matters. Iran’s portrayal of missile strikes as purely retaliatory is central to the regime’s revolutionary ethos, which frames the Islamic Republic as innocent, under constant attack, and needing robust defense capabilities to safeguard the Revolution. After the three Iranian missile strikes in 2017-2018, Khamenei is reported to have sought that Iranian retaliation not harm “regular and non-military people.”201 This emphasis on self-defense and avoiding civilian casualties colors Iran’s weapon selection, since less precise projectiles might miss their target completely, embarrass the regime, and undermine the rationale for retaliation. Moreover, if Iran portrays itself as responding to an attack, Iranian officials will seek to maintain public support by describing foreign aggression as the root of the conflict while ignoring Iranian provocations that may have actually led to the attack.202

- Tehran uses missile strikes to communicate to both domestic and foreign audiences. Iranian officials believe their missiles convey “a very decisive message” to Tehran’s adversaries,203 who draw important conclusions from Iran’s missile strikes.204 To foreign audiences, the retaliatory missile strikes are designed to deter any would-be aggressors by conveying Tehran’s political resolve, military strength, and, more recently, risk tolerance. Following Iran’s 2018 strike on ISIS in eastern Syria, the secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council noted the operation also sent a message to America, as the missiles struck within three miles of U.S. forces.205 Domestically, regime officials want both the elite and the general public to believe that the Islamic Republic is strong206 and that Tehran’s adversaries cannot pressure it into changing course. As Hajizadeh declared after a 2017 Iranian missile operation launched in retaliation for ISIS attacks inside Iran, “We responded to the fireworks of takfiri terrorists with missiles.”207 Hajizadeh echoed this message in 2018, claiming Iran responded “with missiles” to ISIS “bullets.”208

- Iran’s ballistic missile capabilities have improved, but their military effectiveness varies. Iran’s January 2020 precision strikes against the Al-Asad base in Iraq shocked much of the world.209 Although the United States confirmed that no American service members were killed, the regime claimed to have struck America’s “command [and] control center” in Iraq.210 Through the attack, regime officials conveyed an advanced capability that even U.S. military officials acknowledged.211

However, Iran’s precision-strike revolution should not be confused with consistent performance. Everything from missile crew training to proper target selection to pre-strike intelligence collection can determine the success of an attack, not to mention the individual missile’s functionality. For example, Israeli observers have noted that during Iran’s 2017 strike on Syria, just one of the five Zulfiqar missiles hit its target, while the other four landed in the desert.212 Conversely, during its 2018 strike on Kurdish dissidents in northern Iraq, Iran employed a Fateh-110B and fared significantly better. The next strike, against ISIS in eastern Syria in 2018, featured a combined operation employing the modified Qiam with finlets, the Zulfiqar SRBM, and armed drones.213 That operation apparently found more success than Iran’s 2017 strike in eastern Syria,214 with Tehran claiming that 40 ISIS terrorists were killed.215 And in 2022, Iran attacked northern Iraq several times, once in the spring and three times in the fall. Each time, it struck ostensibly civilian targets. Of note, Iran’s IRGC Ground-Forces (IRGC-GF), rather than the IRGC-AF, conducted the latter three operations, which for the first time featured CRBMs rather than SRBMs. Regardless of the unit or missile class, the military effectiveness of Iran’s ballistic missiles remains a toss-up but will likely improve significantly over the medium-to-long term. - Tehran’s own conclusions matter more than Washington’s. Objectively, the Islamic Republic lucked out by not killing any Americans in its January 2020 ballistic missile strikes in Iraq. American deaths likely would have forced the United States to respond militarily.216 But this is not the lesson Tehran took away. A three-part IRIB documentary from 2021 called “Deterrent” asserted that Iranian missile power deterred U.S. retaliation. At the end of that documentary, Hajizadeh argued that Iran had bested its militarily superior foe thanks to Tehran’s willingness to use its power, drawing a sharp distinction between will and capability.217 This increased willingness to use ballistic missiles likely drove Tehran to employ the weapon again in March 2022. Iran allegedly responded to an Israeli threat against Iran from Iraqi territory but ended up striking the home of a Kurdish oil tycoon near Erbil.218

The January 2020 attack marked the first time Iran had conducted a ballistic missile strike against U.S. forces, signaling an increased comfort with direct rather than proxy warfare against a more powerful adversary. America’s previous failure to respond kinetically to Iranian regional escalation may have inadvertently signaled that Washington lacks the will to retaliate. The absence of a U.S. response to Iran’s January 2020 attack likely entrenched this perception: As Hajizadeh said in the aftermath of the strike, “not one bullet was fired towards our missiles.”219 Such a perception appears to be lowering the threshold for overt Iranian aggression using ballistic missiles. Indeed, in late September 2022, the IRGC-GF launched a reported 73 CRBMs from a base in northwestern Iran at Iraqi Kurdistan.220 The attack killed 13 persons, including one U.S. citizen.221 This is the largest reported Iranian missile operation in at least two decades and marks the first known instance in which a U.S. citizen died in an Iranian ballistic missile attack. To date the U.S. has not responded kinetically.

Unpacking Iran’s Arsenal

Ballistic Missile Basics

Ballistic missiles are armed projectiles equipped with guidance systems,222 whereas unguided armed projectiles are classified as rockets. Ballistic missiles can use liquid or solid fuel for propulsion, and both types can be found in the Iranian arsenal. Ballistic missiles differ from cruise missiles (which fall outside the scope of this study) in terms of flightpath, altitude, and engine or motor. While ballistic missiles follow a parabolic flightpath, cruise missiles fly low and parallel to the earth. Depending on their range and if they were fired on a lofted trajectory, ballistic missiles can follow an endoatmospheric or exoatmospheric flightpath. Cruise missiles stay within the atmosphere and use an air-breathing engine (often a turbojet or turbofan, but for significantly higher speeds, a ramjet) for propulsion.

Iran has an evolving land-attack cruise missile (LACM) capability as well as a significant anti-ship cruise missile (ASCM) capability. Cruise and ballistic missiles carry conventional (high-explosive) or unconventional (nuclear, chemical, or biological) payloads. Iran also has other types of ballistic missiles that are not surface-to-surface missiles (SSMs), such as anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), which are designed for naval targets but follow a ballistic trajectory.223

Some ballistic missiles can carry separating warheads, which detach from the missile’s body during flight. These warheads contrast with non-separating warheads, which make an easier target for missile defenses. Ballistic missile warheads can be equipped with unitary or cluster munitions. (The latter munitions shower the targeted area with bomblets prior to impact.) Iran has ballistic missiles that can be outfitted with all of the above.224

Range is another important metric. This report employs range definitions used by the U.S. government: CRBMs can travel up to 300 kilometers. SRBMs travel between 300 and 1,000 kilometers. MRBMs travel between 1,000 and 3,000 kilometers. IRBMs travel between 3,000 and 5,500 kilometers. Finally, ICBMs travel beyond 5,500 kilometers.225

Precision is another measure to track. A missile’s precision is assessed through its circular-error probable (CEP), a calculated radius within which roughly half of all strikes will fall. The smaller the CEP, the more precise the missile and the more useful it is as a battlefield weapon. By way of example, the Scud-B, which Iraq and Iran fired at one another during the Iran-Iraq War,226 has a CEP of 450 meters.227 Conversely, the Fateh family of missiles used in more recent Iranian military operations reportedly has a CEP of 10 meters.228

Organizing Iran’s Ballistic Missiles

There are various ways to group Iran’s ballistic missiles. Some scholars divide them based on class, which prioritizes range. Others have focused on missile family, clustering systems based on their progenitor. Still others divide Iran’s arsenal based on propellant or chronology of development. It is also possible to divide Iran’s missiles by mission or by whether they meet the MTCR understanding of a “nuclear-capable” system. There is no right or wrong way. This report employs a combination of these approaches. Appendix B describes in detail every known ballistic missile in the Iranian arsenal designed for surface-to-surface use, while Table 3 lists those munitions and provides relevant data about each system, drawing on Persian-language reporting. The table and appendix both omit reference to a November 2022 claim by Iranian officials about having built a hypersonic ballistic missile due to the lack of any detail or image.229

Table 3: Known Iranian Ballistic Missiles230

| Name | Meaning | Class | Propellant | Reported Range (km) | Missile Diameter (cm) | Missile Length (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tondar-69231 | Thunder-69 | CRBM232 | Solid | 150233 | – | – |

| Fateh-110 (A/B/C/D) | Conquerer-110 | SRBM | Solid | 250 (A)

300 (B/C/D)234 |

61 | 8.8 |

| Fateh-313 | Conquerer-313 | SRBM | Solid | 500235 | – | – |

| Zulfiqar | Lord of the Spines | SRBM | Solid | 700 | 68 | 10.3 |

| Fateh Mobin | Clear Conqueror | SRBM | Solid | 700236 | – | – |

| Dezful237 | Named after city of Dezful238 | SRBM/MRBM | Solid | ~1,000239 | ~68240 | ~10.3,241 12242 |

| Ra’ad-500243 (a.k.a. Zouhair) | Thunder-500 (Name of companion of Imam Hussein at Karbala) | SRBM | Solid | 500 | – | – |

| Shahid Haj Qassem244 | Martyr Haj Qassem | MRBM | Solid | 1,400245 | ~85-95 | 11 |

| Fath246 (a.k.a BM-120; assumedly Fath-360) | Conquest (Conquest-360) | CRBM | Solid | 80-100, ~130-170,247 or 120248 | 40-50% smaller than Fateh-110, ~30 | 40-50% smaller than Fateh-110, ~4 |

| BM-250249 | N/A | CRBM | Solid | 250 | 45.6 | 7.235 |

| Kheibar Shekan250 | Breaker of Kheibar | MRBM | Solid | 1,450 | – | – |

| Sejjil-2251/Sejjil | Baked Clay-2 | MRBM | Solid | 2,000 | 125 | 17.5,18 |

| Shahab-1 | Meteor-1 | SRBM | Liquid | 300 | 88 | 11 |

| Shahab-2 | Meteor-2 | SRBM | Liquid | 500 | 88 | 11 |

| Qiam-1, Qiam-2 (a.k.a. Modified Qiam) | Uprising-1/2 | SRBM | Liquid | 700 (1,000 for Qiam-2, updated)252 | 88 | 11.5 (11.846 for Qiam-2)253 |

| Shahab-3 | Meteor-3 | MRBM | Liquid | 1,150-2,000254 | 125 | 15.86 |

| Ghadr-1(101) and F/H/S | Magnitude-1(101) and F/H/S | MRBM | Liquid | 1,350-1,950. 1,350 (S), 1,750 (H), and 1,950 (F) | 125 | 15.86 |

| Emad | Pillar | MRBM | Liquid | 1,700-2,000255 | 125 | 15.5 |

| Rezvan256 | Satisfaction/Contentment; Gatekeeper of Paradise | MRBM | Liquid | 1,400 | – | – |

| Khorramshahr, Khorramshahr-2 (a.k.a. Modified Khorramshahr) | Named after city of Khorramshahr | MRBM/potentially IRBM | Liquid | 2,000 (potentially up to 3,000 for Khorramshahr-2)257 | 150 | 13 |

Toward Longer-Range Capabilities: Space/Satellite-Launch Vehicles

In 2011, several Iranian military officials said the Islamic Republic would not produce missiles with a range of over 2,000 kilometers.258 Khamenei himself reportedly called for that range limit.259 Such an injunction would theoretically inhibit Iran from developing IRBMs or ICBMs and thus lock in Tehran’s existing MRBM and SRBM arsenal. Many analysts welcomed the news of Tehran’s voluntary range cap even though it was a political rather than a legal or technical prohibition.

However, this cap did not end Iran’s quest for longer-range missiles. The regime’s space program, including its SLV production and testing, offers another pathway, but under a civilian guise. Tehran has long employed a “civilian” or scientific rationale to justify other security pursuits, like its nuclear program, which always had military dimensions.

As noted earlier, the regime’s quest for status and recognition is a key driver of its military capabilities. Along with a strategy of nuclear hedging, this “status discrepancy,” as Shahram Chubin notes, “accounts for Iran’s space ambitions.”260 Tehran genuinely covets the respect afforded to nations that can put satellites into orbit and develop other space-based capabilities. Iran frames scientific accomplishment, particularly while under sanctions, as the fruits of its defiance against perceived Western attempts to impede Iranian power. But this alone does not define the Islamic Republic’s interest in SLVs.

According to the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency, progress on SLVs can also “aid Iran’s development of longer-range ballistic missiles because SLVs use inherently similar technologies.”261 Likewise, a 2017 report by the U.S. National Air and Space Intelligence Center said, “Tehran’s desire to have a strategic counter to the United States could drive it to field an ICBM. Progress in Iran’s space program could shorten a pathway to an ICBM.”262 The 2020 version of the report reiterated that assessment.263 SLV production and testing teach countries about thrust, staging, and boosters for carrier rockets that can be reconfigured as ICBMs. SLVs and long-range missiles both require guidance systems (to varying degrees) as well as telemetry equipment to inform ground-based crews about mid-flight changes in the projectile’s speed or temperature.

Yet while SLVs share many similarities with ICBMs, they do have differences,264 such as contrasting trajectories based on the engines or motors employed in each projectile.265 More importantly, ICBMs require ablative coatings and heat shields that enable their RVs to re-enter the atmosphere and deliver their payload to the target. SLVs, on the other hand, do not use RVs. As of this writing, the Islamic Republic does not have an ICBM but has tested several different types of SLVs, five of which deserve attention here.

The first two SLVs, the Safir and Simorgh, rely on liquid-propellant engines, are based on the Shahab-3/Nodong-A MRBM, and have achieved mixed results in putting satellites into low-Earth orbit (LEO). Iran first tested the Safir in 2008. The Safir utilizes the Ghadr-1 (which is a Shahab-3 variant) for its first stage and has a smaller second stage.266 The Safir has been used to deliver almost all of Iran’s satellites that remain in LEO. Between 2006 and 2013, however, Iran relied on another liquid-propellant SLV known as the Kavoshgar sounding rocket to put satellites into LEO. While one class of Kavoshgar rockets is reportedly based on the Shahab-3,267 there are several earlier versions modeled on artillery rockets.268 Some of these Kavoshgar rockets continue to be used to support the Iranian space program. In October 2022, for example, Iran used an older Kavoshgar carrier rocket269 to launch an orbital transfer block named the Saman, presumably to function as a tug between satellites in the future.270

Conversely, the Simorgh, which Iran first unveiled in 2010 but tested in 2016, has failed to put a satellite into orbit.271 Despite these failures, Iran will likely continue to test the Simorgh, which is only one of several platforms associated with Iran’s large liquid-propellant SLV program run by the Iranian Space Agency (ISA). These include the prospective272 Sarir SLV at 35 meters long and 2.4 meters in diameter,273 which Tehran hopes will one day put a one-ton payload into a 1,000-kilometer orbit. Also under development is the Soroush SLV, with a diameter of 4 meters,274 which will allegedly be able to put a 15-ton payload into a 300-kilometer orbit.275

Compared to the Safir, the Simorgh is a larger, two-stage SLV that reportedly relies on four Shahab-3 engines for its first stage. Analysts have noted these engines are similar to the North Korean three-stage Unha carrier rocket.276 The U.S. Treasury Department revealed in 2016 that Iranian defense contractors from the Shahid Hemmat Industrial Group (SHIG)277 — a subsidiary of Iran’s Aerospace Industries Organization (AIO),278 which in turn is a subsidiary of Iran’s Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistics (MODAFL)279 — worked with Pyongyang on an 80-ton rocket booster.280 SHIG officials previously attended the launch of the Unha rocket in North Korea in 2012.281 The UN Panel of Experts on North Korea raised these concerns about SLV cooperation in a March 2021 report.282

In a recent letter to the UN secretary general, Israeli officials raised a similar issue related to “unusual activity” from December 2021 that they assessed was “connected to the development of a new, 80-ton thrust liquid propellant engine that was tested at the location. This type of engine could be used for future satellite launch vehicles and could potentially be implemented in intercontinental ballistic missile projects.”283 Open-source experts and imagery analysts continue to raise concerns over Iranian liquid-propellent engine testing, noting that Tehran likely engaged in a long-range or potential liquid-propellant engine test between late May and early June of 2022.284 The location of the test, a facility in Khojir, is believed to be overseen by SHIG.

The other three SLVs tested by Iran, the Qased and the Zuljanah, both employ solid-propellant in at least one stage and are therefore more worrisome. As exemplified by India, nations driven by status and security considerations have used solid-propellant SLVs, and space programs more generally, to develop ICBMs.285