March 24, 2022 | Memo

Engines of Influence

Turkey’s Defense Industry Under Erdogan

Introduction

Turkish weaponry is helping Ukrainian troops fight off the Russian invasion of their homeland.1 The chief of Ukraine’s air force called the Turkish-built TB-2 drones “life-giving” as he confirmed they had struck Russian targets.2 Time magazine called the TB-2 “Ukraine’s Secret Weapon Against Russia.”3 Yet Turkey’s Deputy Foreign Minister Yavuz Selim Kiran underscored that Ankara did not provide these drones to Kyiv as military aid, saying, “They are products Ukraine purchased from a private company.”4 Ankara’s delicate balancing act between Moscow and Kyiv is partly a result of its ongoing attempts to find alternatives to NATO weapons systems by developing an indigenous defense industry, tapping into Ukrainian defense technology, and purchasing the S-400 air defense system from Russia. 5

Turkish weaponry has also shaped the outcomes of several recent clashes in the Middle East and beyond.6 In Syria, the TB-2 helped defeat a Russia-backed Syrian government offensive in Idlib in 2020.7 In Libya, Turkish arms helped turn the tide against an offensive by the self-styled Libyan National Army of Khalifa Haftar.8 In the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Turkish drones contributed to a decisive Azerbaijani victory.9 Turkey’s ongoing effort to launch fixed-wing drones from its first multipurpose amphibious assault ship, the TCG Anadolu, has the potential to bring Turkish drones into action in other conflicts.10 Given their combat record and substantial interest from international buyers, Turkish arms will continue to play a role in combat in multiple theaters of interest to the United States and NATO.

However, there has been a backlash in response to civilian casualties resulting from the use of Turkish drones, as well as Ankara’s lack of concern for how buyers use its weapons. For example, Turkish drone strikes in northeast Syria11 and Iraqi Kurdistan,12 which left children dead or injured, have drawn criticism. In January, following a Turkish drone strike in northeast Syria where a 4-year-old boy lost his leg, Nadine Maenza, the chair of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, called out Ankara’s “drone attacks on civilians” as “destabilizing.”13 Similarly, Ethiopia caused a global outcry in February with its use of Turkish drones in strikes that killed nearly 60 civilians in a displaced people’s camp in the country’s northern region of Tigray.14

The potential roles Turkey’s defense industry can play, both in strengthening NATO by deterring its adversaries and in undermining NATO and its values through trade and partnerships with the alliance’s adversaries, require a concerted transatlantic strategy in relations with Ankara. Over the last few years, the appetite of Western countries to sell weapons systems and components to Turkey has diminished as Ankara’s egregious human rights abuses at home and belligerent policy abroad have strained ties with its NATO allies.15 Many Western governments, including the United States, Canada, Germany, France, Spain, Sweden, and Austria, have instituted certain export restrictions on Turkey. These restrictions have incentivized Ankara to find alternate suppliers and to build a domestic arms industry capable of producing advanced weapons.

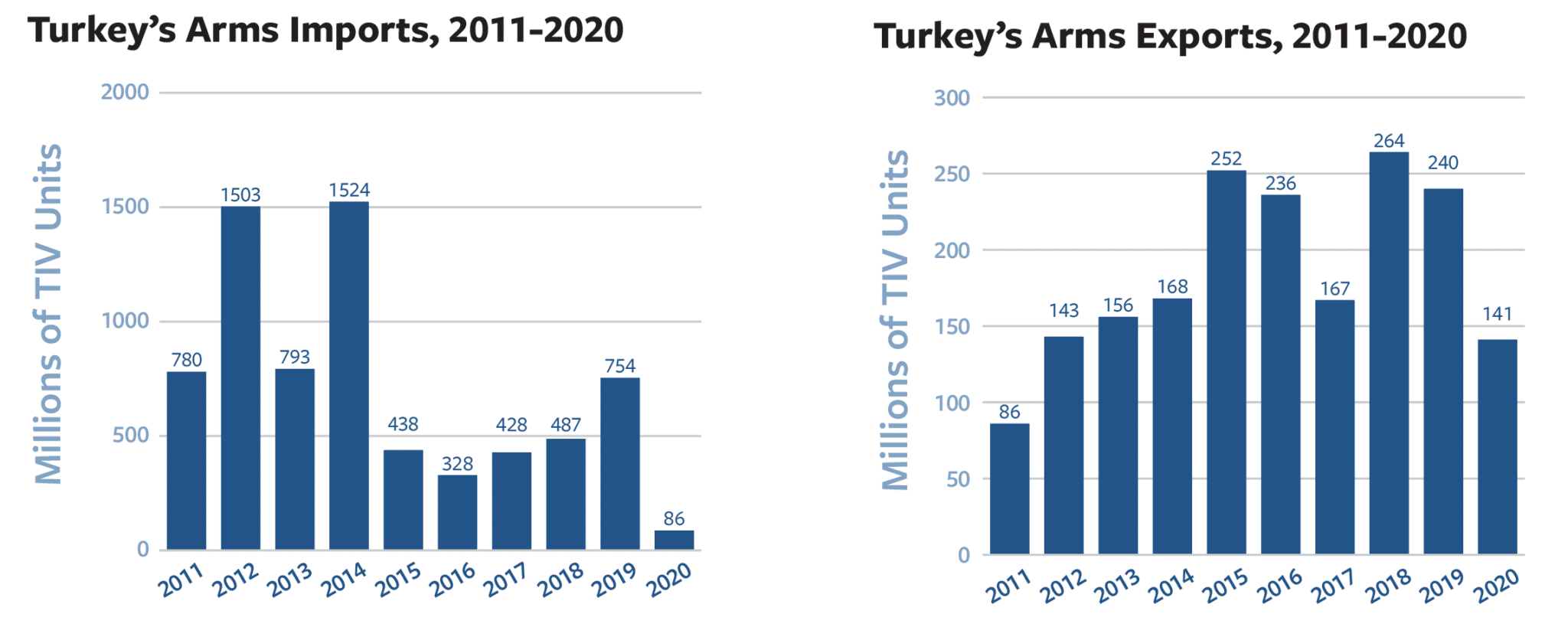

Turkey currently relies on alternate suppliers as a stopgap measure and as a source of technology while building up its domestic arms industry over the long-term. Ankara’s purchase of Russia’s S-400 air defense system16 and its interest in Moscow’s Su-3517 fighters reflect Ankara’s shift to new defense partners. Turkey has been reasonably successful at reducing its dependency on arms imports,18 decreasing them by 59 percent in the five-year period of 2016-2020, as compared to 2011-2015.19 The government hopes that Turkey’s move toward self-sufficiency will eventually enable the country to pursue a foreign and security policy less restricted by its transatlantic allies.

The expansion of Turkey’s domestic arms industry is rooted not only in external factors, but also in domestic political concerns. The domestic production of advanced weapon systems has significant propaganda value, allowing Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to claim he is restoring Turkey to great power status, reminiscent of the Ottoman Empire. While Ankara often announces breakthroughs and new systems and then fails to deliver them, building a potent domestic arms industry may allow that propaganda to become reality.

A strong domestic arms industry could also help lift Turkey’s struggling economy by boosting exports. The Turkish defense sector’s total exports from 2016 through 2020 increased by 30 percent compared to 2011 through 2015. Exports also provide much needed foreign currency in light of Turkey’s depleted net international reserves.20

To date, the Turkish defense industry remains dependent on importing key inputs. The inability to produce engines is a major bottleneck that Ankara seeks to overcome. Turkey’s indigenous arms industry is heavily reliant on importing engines for drones, armored vehicles, and ships, which Ankara then exports as complete systems. Ukraine is the most promising partner for defense cooperation with Turkey. Open-source data indicates significant cooperation on engine manufacturing.

At the same time, Turkey is heavily reliant on the United States and Germany for engines that it puts into armored vehicles. In developing its Altay main battle tank, Ankara tried to source an engine from German tank manufacturer Rheinmetall, but was stymied by an unofficial German embargo following Turkish incursions into northern Syria. Turkey then turned to South Korean manufacturers Doosan and S&T Dynamics to supply Altay’s engine and transmission.21 Yet engine production remains a key vulnerability for the Turkish defense industry.

This report tracks recent trends in the Turkish defense industry and identifies the policy challenges it presents for the United States and its allies. Erdogan’s policies not only provide NATO’s adversaries with opportunities to exploit tensions within the transatlantic alliance, but also could lead to the proliferation of advanced capabilities to state and non-state actors that seek to challenge the United States. By wielding a mixture of positive and negative incentives and engaging with Turkey’s quasi-state defense industries to the exclusion of Erdogan’s loyalists, Washington can help deter Ankara from deepening its defense industry partnerships with Russia and other NATO adversaries. This could represent an important step toward bringing Turkey back into the NATO fold following a potential opposition victory in 2023.

Growth of Military Exports

According to data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), total Turkish arms exports increased by 30 percent in 2016-2020 as compared to 2011-2015, while its imports fell by 59 percent in the 2016-2020 period in comparison to the 2011-2015 period.22 An 81 percent drop in imports from the United States to Turkey accounts for a large portion of the decline. Turkey’s imports from the United States made up 61 percent of its total imports from 2011 to 2015, compared to 29 percent of total imports from 2016 to 2020.

In financial terms, SIPRI data shows that Turkish arms exports rose from $634 million in 2010 to $2.74 billion in 2019. Turkish media reports indicate that $2.78 billion worth of arms was exported in 2020, and $3.22 billion in 2021, although currency fluctuation and lack of independent data make these numbers hard to confirm.23

Turkish arms exports are primarily armored vehicles and ships, which make up 91 percent of the total. However, aircraft exports, especially drones, rose in 2021 and will likely continue to rise over the next several years.24 What nominally Turkish-built armored vehicles, ships, and aircraft have in common is that they are all dependent on foreign engines, meaning that Turkish exports are still dependent upon foreign inputs.

Table 1: Turkish Weapon Exports in Millions of TIV Units by Category, 2016-2020

| | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Total | Share of Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aircraft | -- | -- | -- | 30 | 6 | 36 | 3.44% |

| Armored vehicles | 107 | 93 | 155 | 202 | 135 | 692 | 66.03% |

| Artillery | 9 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 9 | 0.86% |

| Engines | -- | -- | -- | 2 | -- | 2 | 0.38% |

| Missiles | 7 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 22 | 2.10% |

| Sensors | -- | 8 | 16 | -- | -- | 24 | 2.29% |

| Ships | 113 | 62 | 88 | -- | -- | 263 | 25.10% |

| Total | 236 | 167 | 264 | 240 | 141 | 1048 | --- |

A Network of Nepotism

Turkey has a rich array of quasi-state defense industries, which — until Erdogan’s consolidation of power during his first decade in government — used to be closely linked to the country’s once staunchly pro-secular military. Some of these quasi-state enterprises have a history of close cooperation with defense companies from the United States and other NATO nations. This includes cooperation in America’s flagship project for the manufacture of F-16s, integration of their on-board systems, and flight tests by Turkish Aerospace Industries, a U.S.-Turkish joint venture and a precursor to today’s Turkish Aerospace (TUSAS).25

Over the years, the Erdogan government has systematically purged pro-secular board members and executives from quasi-state defense firms and appointed loyalists to key positions.26 Erdogan also helped create a group of private defense companies owned by his loyalists. He did so in part by nationalizing established defense contractors and then re-privatizing them under new ownership. Next, the government directed lucrative government tenders both to those re-privatized firms and to other private companies established or owned by Erdogan loyalists. The government subsequently uses state resources to keep these enterprises above water or acquire them if they go bankrupt. This has established a patronage network in which Erdogan’s close supporters grow wealthy and, in turn, cement Erdogan’s political control over major Turkish industries.

One example that raises questions about the independence of Turkish defense contractors is armored vehicle producer BMC, which the Savings Deposit Insurance Fund of Turkey (TMSF) seized in 2013. Established in 1983, the TMSF steadily lost autonomy after Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) rose to power in 2002. The TMSF ultimately came under the jurisdiction of the president’s office in 2018.27

In 2013, the TMSF seized BMC from a pro-secular Turkish businessman for failing to make payments on debt.28 In May 2014, Ethem Sancak, a businessman who provided political and financial support to Erdogan, bought BMC from TMSF for $360 million, a 20 percent discount.29 Between 2013 and 2017, Sancak funded a wide range of pro-government media outlets.30 In 2017, he joined the AKP’s Central Executive Committee.31 Sancak also benefited when a distant relative of Erdogan invested $100 million in BMC.32

In 2014, Erdogan helped Qatar broker a $300 million deal to acquire a 49.9 percent stake in BMC.33 The following year, Turkish media divulged that this deal allowed a Qatari military attaché serving in Ankara to breach the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations by joining the BMC board, which is privy to sensitive data about classified Turkish government tenders.

It did not end there. Erdogan signed a decree in 2018 leasing Turkey’s national Tank and Pallet Factory to BMC for 25 years and granted BMC an exemption from customs duties, value added taxes, and most corporate taxes.34 This was the first time a private company was able to lease a Turkish military facility. BMC also won a €3.5 billion contract to produce the Altay tank.35 This led opposition lawmakers to question whether it was in Turkey’s security interests to let a Qatari-backed firm participate in a major Turkish defense project.36

The Altay tank project has been stalled for years, partly because of Western sanctions and foreign partners’ refusal to share engine and transmission technology. BMC reportedly sold a majority of its shares in May 2021 to the Turkish steel producer Tosyali Holding, which reportedly also has close ties to Erdogan.37

In short, over the past decade, the BMC saga has entailed the company’s seizure by the Turkish state, the sale of an undervalued BMC to businessmen with close ties to Erdogan, the leasing of a military facility to a private company with heavy Qatari investment, and then a buyout of the struggling company.

Bottleneck: Engines

The ability to acquire engines is the key bottleneck facing the Turkish defense industry. As Turkey’s relationship with the West has declined and Western concerns mount over the use of Turkish weapon systems against civilians in conflicts such as northern Syria and Nagorno-Karabakh, some countries have declined to sell engines or engine components to Ankara.38 Since Turkey cannot yet manufacture military-grade engines domestically, this has left Ankara with two potential courses of action: acquire the necessary inputs from suppliers outside its traditional circle of partners and build up a domestic industry capable of designing and manufacturing engines. Turkey is pursuing both options across an array of systems.

Imports from alternative suppliers are serving as a stopgap measure so that domestic manufacturers have time to enhance their engine building capability. Whether domestic producers will ever reach this goal remains an open question given the inefficiency and corruption in the defense sector. What’s more, Turkey has already encountered a variety of challenges when trying to acquire engines for its drones, jets, helicopters, tanks, and other armored vehicles.

Table 2: Turkish Drones and Engine Models

| Name of Drone | Engine Manufacturer/ Model | Country of Origin (Engine) | Notes |

| Bayraktar TB-2 | -Rotax39 (until October 2020) -Claims of joint production with Ukrspetsexport using Ukrainian engines40 |

Austria/Canada | Due to its record of success in combat, the TB-2 is now one of the most sought-after weapons systems in the world. Its components are subject to export restrictions due to its use in conflicts. |

| Bayraktar Akinci | -TUSAS Engine Industries (TEI)41 -TEI-PD170 turbodiesel aviation engine (as of 2018)42 |

Turkey | As of October 2020,43 TEI began producing a new domestic engine for both the Akinci and TB-3, though exact details are scarce.44 |

| Anka Aksungur | -TEI45 -Two twin-turbodiesel PD-17046 |

Turkey | |

| Karayel | -Vestel Savunma -Intra Defense Technologies and Advanced Electronics Company -97 hp air cooled 4-cylinder engine |

Turkey/Saudi Arabia | Engine production location is unclear;47 however, given that Turkey previously produced the Karayel without Saudi assistance, Turkey is likely the engine manufacturer. |

| Bayraktar TB-3 (under development)48 | -TEI49 | Turkey | Follow-up to successful TB-2 model |

| -Bayraktar MIUS (under development)50 | -Ivchenko-Progress51 | Ukraine | MIUS uses a dual engine system for its AI-25TLT and AI-322F engine variants.52 MIUS will likely be used in conjunction with Turkey’s planned light aircraft carrier TCG Anadolu.53 |

Drone Engines

Turkey’s TB-2 drone is one of the most in-demand items on the international arms market, particularly after its successes in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict as well as the Syrian and Libyan civil wars. It is a medium-altitude, long-endurance armed drone with a proven combat record. Albania,54 Azerbaijan,55 Ethiopia,56 Kyrgyzstan,57 Libya,58 Morocco,59 Niger,60 Pakistan,61 Poland,62 Qatar,63 Tunisia,64 Turkmenistan,65 and Ukraine66 have signed deals to purchase the TB-2, and dozens of other countries have expressed interest.67

However, the TB-2 and other Turkish drones depend on a global supply chain that other countries have disrupted. In 2020, Canada suspended68 the exportation of sensors69 for the TB-2, and Rotax — the Austrian subsidiary of Bombardier Recreational Products, a Canadian company — stopped exporting aircraft engines that same year.70 U.S. companies have come under congressional71 and public72 pressure to stop supplying parts. This is a conundrum for Turkey, as it does not have the capability to domestically manufacture a replacement.

Rotax stopped73 the sale of TB-2 engines in October 2020 following the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, saying that they were intended and certified only for civilian use.74 In other words, Turkey was using foreign, off-the-shelf, non-military engines to produce the drones. Turkey continued to export the TB-275 throughout 2021.76 It is unclear whether Ankara found a new engine or if it continued to use stockpiled Rotax engines.

There are several countries that may be interested in helping Turkey produce or procure replacement engines for the TB-2. Saudi Arabia is co-producing77 the Karayel-SU drone, which was designed by Turkey-based Vestel Defence Industry, and may be interested78 in other Turkish drones. Indonesia has shown an interest in working with Turkish Aerospace Industries.79

Ukraine is the most promising partner for Turkey with regard to engine technology, due to its industrial prowess and aspiration to acquire drones for its conflict with Russia. Ukrainian Deputy Prime Minister Oleh Urusky said in August 2020 that two Ukrainian companies, Ivchenko-Progress and Motor Sich, would hold talks with Turkish defense companies.80 The TB-2’s producer, Baykar, signed engine deals with these two companies in November 2021.81

In 2020, Ukrspetsexport, a state-owned Ukrainian defense manufacturer, announced a joint-venture to produce TB-2s in Ukraine.82 Baykar officials claimed that a replacement engine would be ready by the end of 2021.83 Motor Sich, already a partner for production of Turkish drones engines,84 including for the TB-2, won a contract in November 2021 to supply parts for 30 AI-450T engines in Turkey’s Akinci strike drones.85 The next month, Baykar acquired land in Ukraine to build a factory.86 Around that time, Andriy Yermak, head of the Ukrainian president’s office, stated that production of TB-2s was taking place inside of Ukraine, and that the engines were manufactured in Ukraine.87 Ukraine bought six TB-2s in 2019 and six more in July 2021 for a total of 12, and plans to acquire 24 more through 2022.88

In January of this year, a spokesperson for the Ukrainian Air Force claimed that Kyiv has “approximately 20 Bayraktar drones, but we will not stop there.”89 There are other defense cooperation deals looming between Turkey and Ukraine.

- Ukraine offered Turkey to assess co-production for Antonov’s AN-178 cargo aircraft.90

- Turkish government media say Ukraine may sell a 50 percent stake in Motor Sich to a Turkish state-owned company. 91

- Ukraine and Turkey signed an agreement to cooperate on the development of TF-X fighter jet engines.92

- Turkey will use Ukrainian engines for its heavy class helicopters, the ATAK 2.93

- Ukrainian officials said in 2020 that aircraft manufacturer Antonov hopes to enhance its partnership with Turkey’s state-controlled missile manufacturer Roketsan.94

The future of these cooperation deals will depend on the outcome of the Ukraine war. While a prolonged and extensive Russian invasion could halt cooperation, Kyiv’s effective use of Turkish weaponry could strengthen cooperation with Ankara. Alternatively, if the Kremlin succeeds in installing a puppet regime in Kyiv, the existing Turkish-Russian defense cooperation might extend to cooperation with Ukrainian defense industries under Russian tutelage.

Although many international purchases of the TB-2 result from the drone’s battlefield performances, there is also a diplomatic angle. The family of Erdogan’s son-in-law, Selcuk Bayraktar, owns the company that produces the TB-2. Some governments see TB-2 orders as a means to curry favor with Erdogan.95

This is particularly important for Eastern European states under threat from Russia. Indeed, Erdogan has a history of playing the spoiler within NATO when the alliance seeks to push back against the Kremlin’s aggression.96 In 2020, for example, the Erdogan government blocked97 a NATO defense plan for the Baltic states and Poland for over six months.98 TB-2 purchases are not just a way to strengthen their militaries, but also a means to buy Erdogan’s goodwill in the hope he will not block a unified NATO response to Russian intimidation.

Jet Engine — TF-X

Turkey’s lack of indigenous engines has stalled its development of its purported fifth-generation fighter jet, the TF-X.99 Ankara has turned to numerous suppliers abroad, but to no avail. Notably, Turkey signed a deal with the British company Rolls-Royce to develop an engine,100 but as the Financial Times reported, Rolls-Royce balked in 2019 “due to a dispute over the sharing of intellectual property and the involvement of a Qatari-Turkish company,” 101 namely BMC.102 Turkey has since commissioned TRMotor, which is owned by SSTEK A.S., which itself is owned by Turkey’s defense procurement agency, the Presidency of Defense Industries (SSB), to develop an auxiliary power unit and air turbine start system that may eventually be part of an indigenous engine.103 Last December, Ismail Demir, who leads the SSB, announced that the TF-X program will initially use General Electric’s F110 engine, although General Electric has not confirmed this.104

Russia has also offered to provide engine technology for the TF-X.105 Demir said, “We will negotiate with Russia about [TF-X] parts we want to locally produce.”106 However, there are worries in Turkey that deeper defense cooperation with Moscow would inflame tensions with Washington. Ankara’s purchase of Russia’s S-400 surface-to-air missile system107 led the Trump administration to impose sanctions against Turkey in 2020 pursuant to Section 231 of the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), which targets significant transactions with the Russian defense or intelligence sectors.108

In October 2020, Ukraine and Turkey signed an agreement enabling cooperation on the development of jet engines.109 Despite the lack of progress, Turkish officials remain optimistic that Ankara will be able to produce jet engines indigenously for their advanced fighters by 2029.110

Helicopter Engines

Currently, Turkey imports engines from LHTEC, a joint venture between Rolls-Royce and the U.S.-based Honeywell, to power its T129 ATAK helicopter. Ankara developed the T129 in partnership with Anglo-Italian AgustaWestland and based the helicopter on the Italian Agusta A129 Mangusta platform.

Turkey recently sold six T129s to the Philippines with U.S. approval.111 However, as a result of Washington’s political differences with both Ankara and Islamabad, the United States did not grant Turkey a license to export the same engines to Pakistan.112 On January 5, Pakistan announced it was cancelling its T129 deal with Turkey, opting instead to pursue the Chinese-built Z-10ME.113 It is not certain whether Washington would grant Turkey a license if Iraq moves forward with its reported interest in purchasing 12 of the T129s.114

Additionally, Turkey has been developing and testing domestic helicopter engines produced by the country’s TUSAS Engine Industries (TEI),115 which the country’s ministry of industry and technology projected could save an estimated $60 million in import costs.116 The TEI engine was designed for Turkey’s first indigenous multipurpose helicopter, the Gokbey, which Ankara intends to export as well.117 Ankara has also turned to Ukraine to help produce engines for its heavy class helicopter, the ATAK 2.118

Altay Main Battle Tank Engine

Germany restricted arms exports to Turkey in October 2019 following Erdogan’s military incursion into northeastern Syria to target Washington’s Syrian Kurdish-led partners in the fight against the Islamic State.119 Since that time, Ankara has struggled to find an engine for the Altay. The Altay prototype was powered by a 1,500-horsepower diesel engine from Germany’s MTU Friedrichshafen.120 German defense company Rheinmetall had established a joint venture with Turkey’s BMC to produce engines for the Altay, but as early as 2017, Rheinmetall ran into trouble receiving clearance from German authorities, which cited concerns about Turkey’s democratic backsliding and human rights record.121 BMC is now trying to negotiate with other foreign manufacturers. As of March 2021, BMC had reached an agreement122 with South Korean companies that would supply engines for the Altay and help integrate the technology.123

At the same time, BMC has been developing its own domestically produced engine, the BATU, for the Altay.124 The initial models will still use the engines and transmission supplied by the South Korean companies Doosan and S&T Dynamics, but the next generation will integrate the domestically produced engines. Ankara’s choice of Doosan and S&T Dynamics, both of which use German components, is an attempt to circumvent German restrictions. Korean companies are expected to “de-Germanize” components in the engines and then send them on to Turkey.125

According to BMC, the tests for the BATU engines have been successful thus far, which could accelerate their integration into the Altay. However, Turkey habitually announces successful developments that never materialize.126 Since the announcement, the two Erdogan loyalists who owned 50.1 percent of BMC sold their shares to Tosyali Holding, a Turkish iron and steel manufacturer that also has close ties to Erdogan.127

Other Armored Vehicle Engines

Over the last five years, 66 percent of Turkey’s arms exports were armored vehicles, specifically armored personnel carrier-type vehicles. Most of the engines for these vehicles hail from the American companies Cummins and Caterpillar, with a handful of German companies also represented. These sales do not always appear in SIPRI databases as arms sales, because they are commercial, off-the-shelf engines that can be used for other purposes, like construction.

Table 3: Turkish Armored Vehicle Exports, 2016-2020

| Name of Armored Vehicle | Engine Manufacturer/ Model | Country of Origin (Engine) | Notes |

| T-300 Self-propelled MRL (TRG-300 Tiger) | -MAN Diesel engine128 |

Germany | The Modified Chinese MRL129 merged with German MAN Diesel cross-country truck chassis. |

| Cobra APV | -GM, V8 Diesel -Water cooled turbocharged 6.5L 190HP130 |

United States | The updated Cobra is being developed in conjunction with American AM General131 and Turkey’s Otokar. |

| Ejder Yalcin APV | -Cummins -300-375HP diesel engine132 |

United States | |

| Kirpi APC | -Cummins -ISL9E3+375 turbo diesel engine133 |

United States | |

| Pars APC 25/30 | -Deutz or Caterpillar -Diesel-fueled engines 600HP134 |

Germany or United States | |

| Yoruk APV | -Unknown | Unknown | |

| M-113A300 APC/AIFV APC

|

-Detroit -6V53 two-stroke six-cylinder diesel engine135 |

United States | This old platform has been retrofitted multiple times. |

| Amazon APC | -Cummins -ISB 360 turbocharged, intercooled diesel engine136 |

United States | BMC is working on integrating the Amazon APC with the Songar drone.137 |

| Vuran APC | -Cummins -ISL turbocharged, intercooled diesel engine138 |

United States | The Vuran APC is produced by Turkey’s BMC, which uses Cummins engines. |

| Rabdan IFV | -Caterpillar -Six-cylinder water cooled diesel engine139 |

United States | The Rabdan140 is a modified Emirati version of Otokar’s Arma APC. |

| Hizir APC | -Cummins -ISL turbocharged, intercooled diesel engine141 |

United States |

|

| Arma APC | -Caterpillar -C9 diesel engine142 |

United States |

Export and License Restrictions

Due to Turkish military aggression abroad, the use of Turkish drones in conflicts with heavy civilian casualties, and Turkey’s shift towards Russia, many countries have imposed export and license restrictions on Ankara. These include complete embargoes, partial bans, and restrictions on specific components. The U.S. pause on arms sales, Rotax’s decision not to export aircraft engines, Germany’s engine restrictions, and Canada’s ban on drone optics and targeting systems have been the most difficult for Turkey to manage. Ankara’s recent outreach to Armenia, Egypt, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates to normalize relations, as well as its less belligerent foreign policy rhetoric, are part of Ankara’s attempt to refurbish its image in the face of transatlantic pressure. Erdogan’s tactical moderation shows that coordinated transatlantic action against Ankara in the form of export and license restrictions can be beneficial.

In addition to external pressure from Western governments, there are also growing calls by civil society groups for Ankara to attach humanitarian provisions to its arms sales. Alper Coskun, Turkey’s former ambassador to Azerbaijan, urged Ankara to be more transparent in its drone exports and adopt “due diligence measures such as strict adherence to relevant multilateral export control regimes and the formulation of a national code of conduct with principles to guide drone transfer policies.”143 This follows a 2018 call from a Turkish think tank for Ankara to establish an interdisciplinary center on military and legal ethics, particularly to address the challenges raised by the development of drone technology.144

Table 4: International Export and License Restrictions on Turkey

| Country | Items Embargoed | Reason | Notes |

| Canada and Austria | Light-weight engine used in Turkish Bayraktar TB-2 drones | Turkish drones used in Nagorno-Karabakh conflict | Pursuant to Canadian Bombardier Recreational Product’s (BRP) decision following protests in Canada and Austria. (Rotax is an Austrian subsidiary of Canadian BRP.)145 |

| Canada | Overall military goods and technologies | Turkish violation of end-user assurances146 | Most impacted are camera optics147 used in Turkish Bayraktar TB-2 drone. |

| Czech Republic | Complete arms embargo148 | Pursuant to EU-wide posture; Turkish military intervention in northern Syria | |

| Finland | Complete arms embargo149 | Pursuant to EU-wide posture; Turkish military intervention in northern Syria | |

| Germany | Limiting arms sales to Turkey;150 German bureaucratic slow-rolling of MTU engine for Turkish next-gen battle tanks;151 Germany halts plans to upgrade Turkish Leopard II tanks152 | Pursuant to EU-wide posture; Turkish military intervention in northern Syria | Germany has so far continued the production and sale of six Type 214 submarines to Turkey, to be delivered starting 2022.153 Other deals halted without official arms embargo. |

| Netherlands | Ban on new exports, hold on existing licenses154 | Pursuant to EU-wide posture; Turkish military intervention in northern Syria | |

| Norway | Complete arms embargo155 | Pursuant to EU-wide posture; Turkish military intervention in northern Syria | |

| Spain | Ban on new exports156 | Pursuant to EU-wide posture; Turkish military intervention in northern Syria | |

| Sweden | Complete arms embargo157 | Pursuant to EU-wide posture; Turkish military intervention in northern Syria | |

| United States | Expulsion from F-35 fighter program; Congress has paused arms sales | Turkish purchase of Russian S-400 missile defense system; Turkish military intervention in northern Syria | Congress quietly halted almost all arms sales,158 blocking the deals from moving forward without formal declarations. |

Policy Recommendations

U.S. policy toward Turkey should discourage Ankara’s deepening defense industry cooperation with Russia and other NATO adversaries while laying the groundwork to re-establish a robust U.S.-Turkish defense partnership in a post-Erdogan era. This would entail:

- Incentives and disincentives to discourage Turkey from deepening its defense industry cooperation with Russia and other NATO adversaries. Incentives should include the opportunity to procure NATO military systems. Disincentives should include sanctions under CAATSA, which include sanctions against Turkey’s defense procurement agencies and a ban on U.S. export licenses. Washington needs to manage this strategy carefully. It cannot become an appeasement policy that provides the Erdogan government with easy access to NATO equipment and technology while he undermines the alliance. A different approach will be necessary for each weapon system based on its characteristics.

- Offering certain buyers of Turkish arms the opportunity to purchase comparable NATO systems. Many U.S. allies and partners outside of NATO do not approve of Erdogan’s foreign and security policy but feel obliged — since they cannot procure comparable NATO equipment — to purchase hardware from Turkey’s defense companies owned by Erdogan’s loyalists. The U.S. and other NATO members should calibrate export restrictions to give responsible buyers an alternative. Unmanned systems are one of these buyers’ top interests.

- A congressional request to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) to determine whether the use of U.S. military and dual-use technology in Turkish arms exports is consistent with U.S. law. Turkey’s past use of other countries’ technology in military projects without proper authorization or licensing raises the question of whether Turkey is doing the same with U.S. technology, particularly dual-use engines. Washington should also employ various anti-corruption measures, including Global Magnitsky sanctions159 and the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act,160 to target corrupt actors and to dissuade reputable businesses from engaging with them.

- Preparing plans to rebuild strong defense industry partnerships with Turkey in the event of an opposition victory in the country’s 2023 presidential and parliamentary elections.161 Previously, Turkey was not only a key importer of U.S. equipment and technology but also an integral part of NATO’s supply chains. Today, maintaining institutional channels with Turkey’s quasi-state defense companies, which can help restore cooperative relations with the United States and other NATO members in a post-Erdogan era, would be prudent. The prospect of future partnerships would provide incentives for Turkey’s eventual return to the NATO fold and boost the country’s legitimate defense industry players.

The invasion of Ukraine has shown that NATO will continue to face significant political and military challenges from Russia in the years to come. Although the Erdogan government has pursued a balancing act between Russia and Ukraine, Ankara is beginning to show signs of growing concern about Moscow’s irredentist policies and may be interested in mending ties with the West.162 Hence, the Ukraine war offers NATO a unique opportunity to weaken Putin’s influence over Ankara. Policies that incentivize Ankara to end its growing defense cooperation with Moscow and other NATO adversaries will be crucial to safeguarding the integrity of the transatlantic alliance. Returning Turkey and its defense industry to their pro-Western orientation remains a crucial task for strengthening NATO’s southeastern flank.