December 15, 2020 | Defending Forward Monograph

Avoiding a Self-Inflicted Wound in the Sinai

December 15, 2020 | Defending Forward Monograph

Avoiding a Self-Inflicted Wound in the Sinai

Following Israel’s historic peace agreements with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain on September 15, 2020, it is reasonable for Americans to ask why U.S. troops should continue to serve in the Sinai to prevent conflict between Israel and Egypt – two governments that made peace more than four decades ago.1 In fact, as part of the Pentagon’s ongoing review of U.S. global military posture, designed to free up finite resources for higher priorities, former Secretary of Defense Mark Esper sought to end the U.S. military’s role in the Multinational Force and Observers (MFO), an independent international organization designed to maintain peace between Israel and Egypt.2 However, ending the MFO mission would be a penny-wise and pound-foolish mistake. The MFO helps achieve key objectives in the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS).3

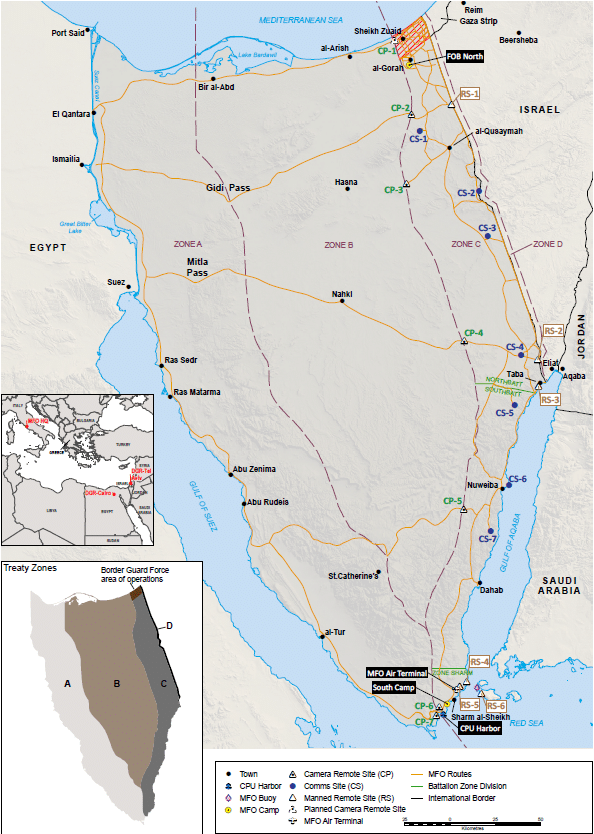

The MFO “mission is to supervise the implementation of the security provisions of the [1979] Egyptian-Israeli Treaty of Peace and employ best efforts to prevent any violation of its terms.”4 Today, the MFO consists of approximately 1,154 troops in the Sinai from 13 nations. The American military contingent is the largest, with 452 service members, down from a high of more than 1,150 service members in 1986.5 Almost half of the U.S. military contingent comes from the Army National Guard or Reserve.

Multinational Force and Observers (MFO) Sinai map. (Photo via MFO).

In addition to personnel in the Sinai, the MFO maintains a headquarters in Rome as well as offices in Cairo and Tel Aviv. The combination of observers on the ground and offices in Egypt and Israel provides the MFO director general the ability to authoritatively tackle developments in the Sinai Peninsula, utilizing a unique and direct line of communication with both countries. This line of communication, says former U.S. Ambassador to Egypt (2011–2013) Anne Patterson, is difficult for any third country or embassy to emulate. In this way, the MFO has helped to prevent war between Egypt and Israel for almost four decades. This stands in stark contrast to five wars between Egypt and Israel in the 33 years preceding the MFO’s establishment.

Skeptics challenge this MFO accomplishment by dismissing peace as inevitable or a foregone conclusion. Nothing could be further from the truth. Consider the MFO’s role during an August 2012 crisis described in a recent report by Israeli Brigadier General (Res.) Assaf Orion and Canadian Major General (Ret.) Denis Thompson. Jihadists killed 16 Egyptian border guards and then used their armored vehicles to attack Israeli forces. Cairo then sent a massive military force into Sinai that was not coordinated with Israel, sparking grave concern there.

Orion and Thompson note that Ambassador David Satterfield, then the director general of the MFO, shuttled between Egypt, Israel, and the Sinai, “narrowing the gaps in understanding, carrying messages, bringing Washington’s weight and interests to the table, and devising procedures to address the new situation and allay the parties’ concerns.”

Orion and Thompson argue persuasively that the MFO’s “unique combination [of] unwavering U.S. support, world-class diplomacy, high levels of access and trust in both capitals, excellent field-monitoring capabilities, and the U.S. military as a backbone” played a decisive role in defusing tensions between Egypt and Israel.6

Some may dismiss this anecdote as no longer relevant due to the relatively stable and constructive relations that Jerusalem and Cairo currently enjoy. However, the revolutions that brought deeply anti-Israel regimes to power in Iran in 1979 and Egypt in 2011–2012 are important examples of how confident predictions in the Middle East can quickly unravel. The dangers are still evident in Egypt, where ill feeling toward Israel among the general population remains widespread.

With lingering concerns about instability in post-revolutionary Egypt, the benefits of the MFO to U.S. national security interests are quite clear. The NDS established as one its top priorities “[d]efending allies from military aggression.” The MFO accomplishes exactly that for Israel – America’s closest and most reliable ally in the Middle East.

Furthermore, the NDS says, the U.S. military “will foster a stable and secure Middle East that denies safe havens for terrorists, is not dominated by any power hostile to the United States, and that contributes to stable global energy markets and secure trade routes.”7 The MFO supports each of the four elements of that policy.

The MFO has played an indisputable role in facilitating a more “stable and secure Middle East.” The peace that the MFO has sustained served as a foundation for Israel’s peace with Jordan in 1994 and ultimately Israel’s peace with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain this year. While new conflict between Egypt and Israel is an unlikely prospect in the near-term, military analysts understand that risk is measured in terms of both likelihood and severity, and it is unwise to neglect the latter consideration.

The NDS also prioritizes denying “safe haven for terrorists.” The Sinai is an area of weak central authority, home to a significant terrorist insurgency that includes militants who have sworn allegiance to ISIS.8 Israel’s confidence in the MFO’s treaty verification processes allows Egypt to deploy additional combat power to Sinai to address the ongoing insurgency. The MFO’s ability to monitor these exceptional temporary deployments mitigates Israel’s legitimate concerns about the re-militarization of Sinai. The transparency and communication channels provided by the MFO have been indispensable in navigating this process.

The U.S. military presence in the Sinai also supports the NDS’ goal of ensuring the region is “not dominated by any power hostile to the United States.” Underscoring the fact that great power competition occurs in the Middle East, too, the Russian navy is increasingly active in the eastern Mediterranean, while Russian regular and irregular forces operate in Syria and Libya. Moscow works hard to cultivate relationships with Cairo, conducting a large air defense exercise in Egypt in 2019 and helping the country build a nuclear reactor.9

Meanwhile, the People’s Republic of China established its first overseas military outpost in Djibouti in 2017 at the opposite end of the Red Sea from the Suez Canal. As part of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese companies pursued a lease arrangement at Israel’s Haifa Port and ownership of Greece’s Port of Piraeus.10 In short, Moscow and Beijing would almost certainly leap to exploit an unforced American error in the Sinai.

Finally, the U.S. military contingent in the MFO supports the NDS’ objective of contributing to “stable global energy markets and secure trade routes” in the Middle East.11 While this objective is certainly not explicitly part of the MFO’s mission, it is worth remembering that the Suez Canal, one of the world’s most important maritime and energy chokepoints, sits adjacent to the Sinai Peninsula. According to the U.S. Energy Information Agency, oil flowing through the Suez Canal and nearby SUMED pipeline accounted for roughly 9 percent of total worldwide seaborne-traded petroleum in 2017. They were responsible for 8 percent of global liquefied natural gas trade, as well.12 The Suez Canal is also vital for the U.S. Navy, which regularly sends vessels through the canal.

Leaders assigned to 1st Squadron, 2nd Cavalry Regiment salute the MFO commander during his inspection of troops while participating in the unit’s MFO award ceremony held in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt. (Photo by U.S. Army)

Having a U.S. military force adjacent to this important chokepoint connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea and beyond is an asset not to be relinquished. It is not hard to envision a scenario in which a U.S. withdrawal from the MFO results in the collapse of the organization. The United States provides a large portion of the force-protection capability for the MFO, and most of the other MFO nations contribute troops based on their relationship with Washington, which provides the majority of the personnel. If Washington were to pull its military contingent from the MFO, many other contributing nations would worry for the safety of their forces. Some nations might no longer see benefit in retaining troops there.

Beijing or Moscow would likely step into the vacuum created by an American departure, seeking to establish a new civil or military presence in the Sinai.13 Ironically, in such a scenario, an American reduction of its modest military commitment to compete more effectively with China and Russia elsewhere would gift Beijing and Moscow a coveted strategic outpost vital to energy, economic, and military security at the intersection of Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Thankfully, key leaders in Congress appreciate the bigger picture. In an extraordinary bipartisan effort, the Democrat and Republican leaders of the House and Senate Foreign Relations, Armed Services, and Appropriations committees sent a letter on May 13, 2020, to then-Secretary of Defense Mark Esper and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo regarding the MFO.14 The legislators warned that a withdrawal from the MFO would represent a “grave mistake” that could “ultimately make it more difficult to implement the NDS.”15

The Pentagon is right to review U.S. military posture in every combatant command to ensure an optimal military posture that fully aligns ends and means. In the Middle East, an objective review would demonstrate that ending the modest U.S. military contribution to the MFO would endanger key NDS objectives and represent a short-sighted and self-inflicted wound to American national security interests.

The views expressed or implied in this commentary are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Strategic Command, the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or any other U.S. government agency. A similar version of this chapter originally appeared in Defense One on October 15, 2020.16