December 15, 2020 | Defending Forward Monograph

American Interests in the Eastern Mediterranean

December 15, 2020 | Defending Forward Monograph

American Interests in the Eastern Mediterranean

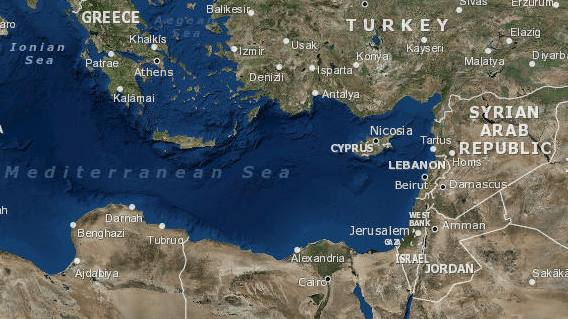

The Eastern Mediterranean’s strategic location at the nexus of Africa, Asia, and Europe has made the region an epicenter of great power competition for over two millennia. It is no coincidence that U.S. pushback against Soviet expansionism began here in 1947 with the Greek-Turkish aid package as part of the Truman Doctrine.1 Although the region remained a focal point of U.S. grand strategy during the Cold War, its importance waned as the U.S.-Soviet conflict ended and as Washington turned its attention farther east following the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

The Obama administration’s “pivot” to Asia also signaled to Mediterranean littoral powers that the United States was leaving the region to its own devices. After Libya became the first case of what one of President Obama’s advisors called “leading from behind,” both state and non-state actors revised their respective ambitions and strategies in anticipation of a reduced American role in the years ahead.2 The Trump administration’s conflicting signals about U.S. interests and commitment, including attempts to withdraw U.S. troops from Syria, only deepened the sense that the United States is quitting the region.3

Map of the Eastern Mediterranean region (Photo via The World Factbook 2020. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 2020)

There are two key reasons why the United States should urgently develop a coherent strategic vision for the Eastern Mediterranean. First, a growing list of state and non-state adversaries has filled the void in the region, posing a mounting threat to the United States, its treaty allies, and its critical partners. Second, Turkey – once a pro-Western bulwark on NATO’s southeastern flank – has become a belligerent challenger following almost 18 years of rule by the country’s Islamist strongman Recep Tayyip Erdogan.4 Ankara’s hostile posture not only targets Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, and Israel, but also imperils U.S. efforts to promote regional energy development that would reduce Europe’s dependence on Russian natural gas. All of this requires an urgent recalibration of U.S. strategy in the region.5

The challenges do not end there, however. The Syrian Civil War has allowed Russia and Iran to expand their footprint in parts of the country controlled by the regime of Bashar al-Assad. The Kremlin’s bases and advanced air defenses along Syria’s Mediterranean coast pose a growing threat to the United States and its allies. Iran’s extensive proxy network, through Hezbollah and other Shiite militias, exerts virtually unchallenged political and military influence in Syria and Lebanon and has given Iran an opportunity to extend a “land bridge” to the Mediterranean.6 Tehran’s provision of precision-guided munitions to Hezbollah is a game changer, potentially leaving Israel little choice but to undertake a major military effort in Lebanon against the terrorist organization – something that could spark a larger war with Hezbollah’s benefactors in Tehran.7

Non-state actors such as the Islamic State, al-Qaeda, and Hezbollah continue to threaten conventional militaries. The rapid flow of foreign fighters throughout the region, including Turkey’s airlift of Syrian jihadists to Libya, underscores the difficulties of containing non-state actors, particularly when they receive assistance from state sponsors.8

The Mediterranean Sea, for millennia a thoroughfare for population movements between Africa, Asia, and Europe, is once again an entrepot for irregular migration into Europe. Mass displacement of people, and the ensuing brain drain and capital flight, not only poses challenges to sending states, but also destabilizes EU member states by catalyzing populist/nationalist movements that have frequently advocated pro-Russia policies. The vulnerability of these democracies to an influx of refugees has allowed Russia and Turkey to weaponize population displacement as part of their respective asymmetric strategies.9

What elevates all these challenges to a new level is Turkey’s Islamist turn and increasingly rogue behavior. This includes Ankara’s purchase of the S-400 air defense system from Russia, gunboat diplomacy to challenge maritime borders, proxy warfare in Libya, weaponization of migrants, patronage of the Muslim Brotherhood and Hamas, and willingness to work with other jihadist proxies.10 Although Ankara often presents itself as a counterweight to Russia and Iran in the region, Erdogan’s Turkey is increasingly part of the problem. Ankara has time and again enabled state and non-state adversaries of the United States and played a spoiler role within the transatlantic alliance.11

Despite these serious challenges, the discovery of significant hydrocarbon resources in the Eastern Mediterranean offers opportunities to strengthen Washington’s posture in the region. Hoping to exploit Mediterranean natural gas reserves, a number of key players, including Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority, met in Cairo in January 2019 to establish the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum.12 France subsequently asked to join the forum, and the United States has applied to become a permanent observer.13

Turkey’s truculence has pushed several states, including Cyprus, Egypt, and Greece, to look for ways to deepen regional political and military cooperation with the Unites States. Following calls to lift the U.S. arms embargo on Cyprus, the bipartisan Eastern Mediterranean Security and Energy Partnership Act signed into law in December 2019 did just that.14 It also authorizes the establishment of a United States-Eastern Mediterranean Energy Center to facilitate energy cooperation among the United States, Israel, Greece, and Cyprus; authorizes Foreign Military Financing assistance for Greece; and provides International Military Education and Training assistance for Greece and Cyprus. 15

To meet the rising challenges and take advantage of the emerging opportunities in the Eastern Mediterranean, the United States must treat the region as a coherent strategic entity and overcome organizational stovepipes within the national security bureaucracy that impede sound policymaking. The U.S. administration should unequivocally convey its commitment to the region, politically and militarily. Recent steps to reassert U.S. military presence in the Eastern Mediterranean are a good start, but Washington’s current regional force posture remains a shadow of its former self and insufficient to deter adversaries.

To this end, given the region’s vital maritime chokepoints and sea lines of communication, the United States should continue to enhance its naval presence in the region and defense cooperation with Greece, building on recent agreements announced in Crete by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis.16 Maintaining a small ground presence in northeast Syria to prevent an Iranian land bridge to the Mediterranean should also be part of the U.S. strategic calculus.

CH-47 Chinook flight engineer assigned to B Co “Big Windy,” 1-214th General Support Aviation Battalion during a training flight over the island of Cyprus on January 15, 2020. (Photo by Major Robert Fellingham)

Deepening energy cooperation also serves as a pillar of U.S. strategy for the Eastern Mediterranean. Washington should appoint a special envoy for the Eastern Mediterranean to work closely with the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum and challenge the Turkish government’s disruptive offshore claims. The United States can also establish a U.S.-led annual combined joint maritime exercise focused on maritime energy security that brings Israel, Greece, Cyprus, and interested Arab countries together.

In Libya, the security vacuum has emboldened both Turkish and Russian attempts to destabilize the country.17 To mitigate the resulting political, military, and humanitarian crises that are spilling over into the Eastern Mediterranean and Europe, the United States must assume a diplomatic leadership role and work harder to achieve a negotiated solution in coordination with the European Union.18

The United States also needs to offer stronger incentives and disincentives, including sanctions (for example, under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act and the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act), to induce Ankara to reverse its malign behavior.19 As the downturn in U.S.-Turkish relations puts the future of U.S. access to Turkey’s Incirlik Air Base at risk, Washington must also make contingency plans for alternative basing options.20

As during the Cold War, the Eastern Mediterranean is re-emerging as a prime arena for regional and great power competition. Energy resources loom large, with major implications for freedom of the seas and the regional balance of power. The United States has over the past decade stayed largely aloof from this zone of intensifying crisis, but Washington cannot remain disengaged for much longer before Russian and Turkish actions further destabilize the region.

Turkey’s new interventionism, in particular, raises grave concerns because it has relied on local Islamist proxies and increasingly on surrogate forces recruited from Islamist militias that have been fighting in Syria. Exporting these groups to Libya has intensified the conflict there. Their presence also raises troubling questions about these jihadists’ potential onward movement from North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean to NATO allies in Europe and ultimately the U.S. homeland.

There are significant bureaucratic impediments that Washington must overcome to address these threats. Competing authorities exist between different combatant commands and State Department geographic bureaus. But the escalating tensions, including among NATO member states such as Italy and France, demand U.S. leadership and attention. Failure to prioritize the Eastern Mediterranean will condemn it to a continued downward spiral with baleful consequences for the region, Europe, and ultimately the United States itself.