June 24, 2020 | Policy Brief

Cratering Economy Drives Iranian Rial to All-Time Low

June 24, 2020 | Policy Brief

Cratering Economy Drives Iranian Rial to All-Time Low

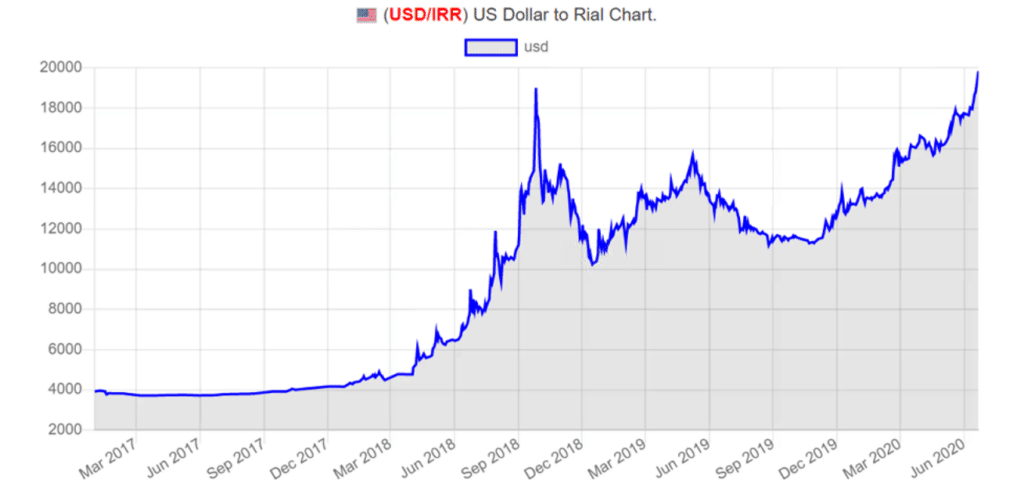

The Iranian rial has lost 10 percent of its value over the past two weeks, and more than 30 percent since the start of the calendar year. The regime may still have sufficient hard currency reserves to end the current freefall, especially if authorities crack down on unregulated exchanges, yet such efforts will only weaken the ability of the Islamic Republic to resist the Trump administration’s maximum pressure policy.

The U.S. dollar, which was worth 70 rials in 1979 before the Islamic Revolution, now trades at more than 200,000 rials. It traded at 37,600 when President Donald Trump took office, before losing almost 80 percent of its value from December 2017 through late September 2018, when the rial reached its previous low of 190,000 to the dollar. At that point, Tehran increased the supply of hard currency and suppressed demand by outlawing private exchanges and initiating a campaign of arrests and even executions for currency and precious metals traders. These efforts enabled the rial to claw back almost half of its losses within three months, although black markets remain.

The freefall that began this January is first and foremost a correction of the rial’s value in response to macroeconomic distress. Iran experienced consecutive years of stagflation – recession plus high inflation – in 2018 and 2019. All indicators point to a third consecutive year. Yet in the latter half of 2019, the rial gained more than 30 percent against the dollar. Market fundamentals tend not to remain out of alignment for so long.

The freefall is also a sign of Tehran’s diminishing hard currency reserves and, more importantly, the decline of accessible reserves. The country’s sovereign wealth fund includes an estimated $15 billion to $20 billion of liquid assets despite an overall value of roughly $90 billion. The International Monetary Fund estimates that the Islamic Republic has $75 billion to $80 billion in foreign reserves, yet this consists mainly of money sitting in foreign escrow funds. This money is available for needs such as purchasing medical equipment and pharmaceutical goods abroad, but is not fully accessible.

The sanctions-driven collapse of Iranian exports of crude oil, as well as the collapse in oil prices, has deprived Iranian of the most important means of replenishing its reserves. Tehran’s exports now appear to have reached a record low of 70,000 barrels per day, compared to 2.5 million per day prior to the U.S. withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal. Furthermore, the latest data from the NIMA market, a currency market for exporters and importers, show that the repatriation of hard currency generated by non-oil exports has dropped significantly over the last few months. At the same time, the price of the dollar on the NIMA exchange has been dramatically increasing.

An uptick in demand for hard currency may also be pushing the dollar higher. This higher demand is partly the result of the reopening of the Iranian economy as the government lifts pandemic-related restrictions. In addition, financial analysts and institutional investors watching the Tehran Stock Exchange have been worried that the market’s dramatic gains are a bubble about to burst. In response, they may have begun to hedge via investment in the currency and precious metals markets.

Finally, a steep budget deficit, aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic, may be aiding the dollar’s rise. As the largest supplier of hard currency, the regime has an incentive to let the dollar appreciate, since this increases the number of rials earned for each dollar sold by the central bank.

The depreciation of the rial and the inflation likely to follow will both mitigate Iran’s growing trade deficit. A weaker rial will make the price of non-oil exports more competitive while reducing demand for imports. So far, Washington has not been successful in cutting Iran’s non-oil exports, although it has been more effective at preventing the repatriation of revenue this trade generates.

As it did in 2018, the Islamic Republic may succeed in arresting the decline of the rial. Yet if Washington’s maximum pressure campaign continues, another plunge may only be a matter of time. In the meantime, Tehran may escalate its aggression against both its neighbors and Persian Gulf commerce to create diplomatic pressure for sanctions relief.

At the broadest level, the fall of the rial reflects the abysmal state of the Iranian economy under the Islamic Republic. Corruption, mismanagement, and an adventurist foreign policy have caused four decades of misery, whose primary victims are the Iranian people.

Saeed Ghasseminejad is a senior Iran and financial economics advisor at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), where he also contributes to FDD’s Center on Economic and Financial Power (CEFP). For more analysis from Saeed and CEFP, please subscribe HERE. Follow Saeed on Twitter @SGhasseminejad. Follow FDD on Twitter @FDD and @FDD_CEFP. FDD is a Washington, DC-based, nonpartisan research institute focusing on national security and foreign policy.