June 2, 2020 | Policy Brief

Tehran’s Flawed Plans to Fight Inflation

June 2, 2020 | Policy Brief

Tehran’s Flawed Plans to Fight Inflation

The Central Bank of Iran (CBI) announced an inflation target last week of 22 percent for the current Persian calendar year, which lasts from March 2020 to March 2021. After a two-year period during which inflation shot from single digits to more than 40 percent, Tehran hopes to suppress both the rate of inflation and its volatility by relying in part on market-based mechanisms.

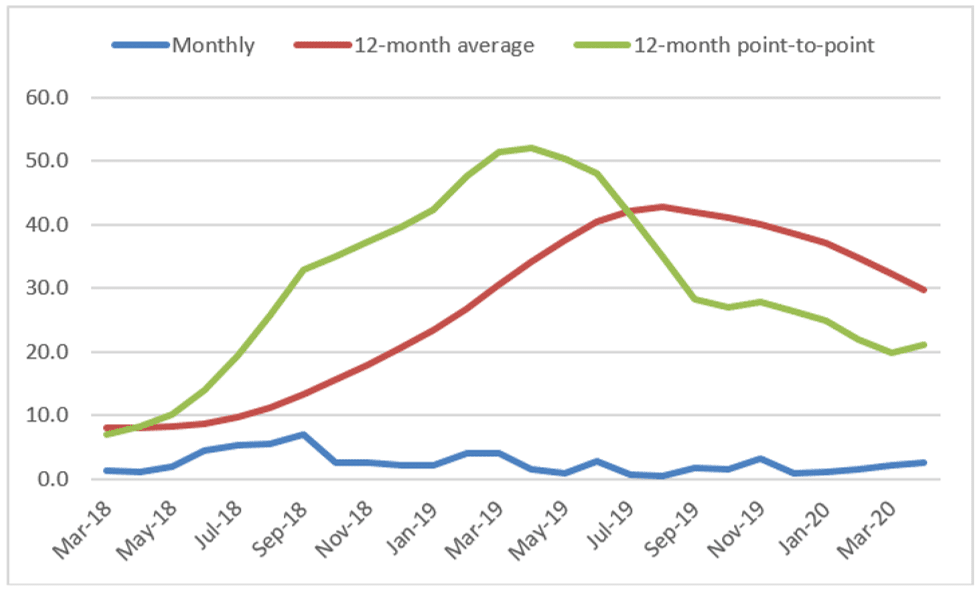

The CBI’s inflation target is more optimistic than the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF’s) latest forecast, which projects 34 percent average yearly inflation in 2020. That figure falls between the 31 percent figure for 2018 and 41 percent for 2019, as reported by the IMF. These annualized figures smooth out some of the sharpest variations in Iran’s point-to-point inflation rate, which measures the change in consumer prices for a given month compared to that same month one year earlier. In April 2019, point-to-point inflation peaked at 52.1 percent, according to the Statistical Center of Iran, before retreating to just 21 percent in April 2020. The average annual rate has also declined, a positive signal for Iran’s economy, which is struggling under the weight of both U.S. sanctions and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since January, the CBI has been engaging in open market operations, a term that refers to a central bank’s sale or purchase of securities to regulate the money supply, which serves as an indirect means of controlling inflation. The CBI has been trying to create an interest rate corridor that would reduce uncertainty in the marketplace while keeping inflation under control. This move to a market-based approach represents a marked change from the regime’s efforts to impose interest rates on Iranian banks, a policy dating back to the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Despite such mandates, market rates rose well above those dictated by the government.

Figure 1: Three Measures of Inflation in Iran

According to the CBI, Iran’s money supply increased 9 percent in the winter quarter of 2020, the highest quarterly rate of growth in four years. In the previous Persian calendar year (March 2019 to March 2020), the point-to-point growth of the money supply was 31.3 percent, just a few points lower than annual inflation. There are also reports of a significant increase in the money supply in March and April of this year. The CBI denies these reports but has refused to provide data of its own.

The weakness of Iran’s currency, the rial, also limits the CBI’s ability to fight inflation. Since January, the rial has lost 25 percent of its value against the dollar on Iran’s unregulated exchanges, where a dollar now costs 177,400 rials. However, with regard to inflation, the relatively small unregulated exchanges may have less impact than the value of the rial in what is known as the NIMA market, a regime-controlled exchange for importers and exporters. While the rial trades at a higher value in the NIMA market – currently about 160,000 per dollar – the dollar gained 47 percent year-on-year against the rial as of April 2020.

To protect its very limited reserves of hard currency, Tehran has been removing items from the basket of basic goods that it subsidizes through a cheap rial-dollar exchange rate. The regime has ample reason to guard its reserves, but the cost of doing so is higher inflation. Last month, for example, Tehran took away rice importers’ access to the regime’s scarce supply of subsidized hard currency. Instead of buying subsidized dollars at the official rate of 42,000 rials, rice importers will have to turn to the NIMA market, where the rate is close to 160,000 rials.

Another bad sign for Tehran is the rising monthly inflation rate, which went from 0.8 percent in December to 2.6 percent in April. This suggests that Iran’s trend of declining annual inflation may be masking less favorable developments.

The CBI’s optimistic inflation target should not cloud the reality of how few effective tools it has to restrain rapid growth in Iranians’ cost of living. At some point, the regime may have to negotiate on Washington’s terms for relief from sanctions.

Saeed Ghasseminejad is a senior Iran and financial economics advisor at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), where he also contributes to FDD’s Center on Economic and Financial Power (CEFP). For more analysis from Saeed and CEFP, please subscribe HERE. Follow Saeed on Twitter @SGhasseminejad. Follow FDD on Twitter @FDD and @FDD_CEFP. FDD is a Washington, DC-based, nonpartisan research institute focusing on national security and foreign policy