May 11, 2020 | Insight

U.S. Sanctions on Iran: Is Natural Gas Next?

May 11, 2020 | Insight

U.S. Sanctions on Iran: Is Natural Gas Next?

The Trump administration’s maximum pressure campaign is having a significant impact on Iran’s macroeconomic stability and draining the government’s export earnings and reserves. As Iranian oil exports plunge, Iran’s regional and non-oil trade remains an important sanctions target. Iran is the world’s third-largest producer of natural gas, and it holds the world’s second-largest gas reserves. Iran relies heavily on its domestic natural gas production. Indeed, natural gas comprises close to 70 percent of its domestic energy consumption. By comparison, natural gas comprises 31 percent of the energy consumption in the United States, 24 percent in Germany, and 15 percent in Norway.

According to the budget submitted to the Iranian Majles at the end of 2019, the regime anticipated earning $4 billion in revenue from natural gas export sales this year, amounting to roughly 3.5 percent of Iran’s budget. Iran exports natural gas to Turkey, Iraq, and Armenia. While U.S. sanctions do not explicitly target Iranian natural gas exported by pipeline, U.S. sanctions are applicable to financial transactions that facilitate such sales, and payments for Iranian natural gas must be held in escrow accounts in the importing country and not made to Iran. The Trump administration has requested that each buyer demonstrate that it is reducing imports over time.

The administration can target Iranian natural gas exports, since Turkey, Iraq, and Armenia have alternatives for new sources of gas or substitute fuels.

Turkey

For over a decade, Turkey was Iran’s main gas export market. However, in the last two years, Turkey has lowered its imports from Iran and Russia and increased imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) and pipeline gas imports from Azerbaijan. Iran has dropped from Turkey’s second-largest gas supplier to its fourth-largest.

Ankara has made this shift partly to please Washington. Turkey not only has cut back on Iranian imports, but it has also imported significant quantities of U.S. LNG. The 2018 inauguration of the Southern Gas Corridor from Azerbaijan to Turkey has also afforded Ankara an opportunity to import from a low-cost and politically reliable source. This has also benefited Turkish companies that invested in the gas production and pipeline.

Turkey may end up ceasing Iranian gas imports sooner rather than later. On March 31, a gas pipeline from Iran to Turkey was attacked, disabling its operation. While pipelines can often be restored within a week after attacks of this type, Turkey and Iran have not yet done so. The National Iranian Gas Company blamed Kurdish militant groups for the attack; Turkish officials have not commented.

Iraq

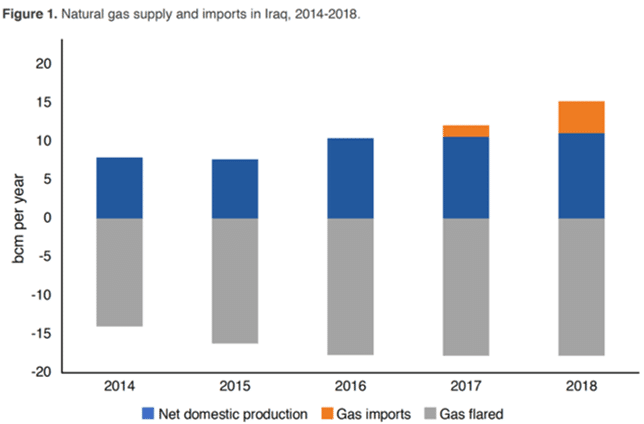

Iraq has extensive local natural gas reserves but has taken few steps to harness them. According to the International Energy Agency, more than half of the natural gas produced in Iraq, most of which is released during oil production, is burned off, or “flared.” In fact, Iraq is one the top three countries in the world in the amount of gas it flares. Over the years, major energy companies have attempted to convince Iraq to allow them to invest in capturing the flared gas, but to no avail, potentially because Iran-backed actors in Iraq benefit by keeping Iraq hooked on Iranian energy. If the government were to acquiesce, Iraq could be self-sufficient and even export natural gas. Iraqi government estimates suggest that Iraq would need more than $10 billion in new infrastructure to accomplish this.

To meet its gas needs, Iraq imports approximately 4 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas annually from Iran, a quarter of Iraq’s gas consumption. The imports began in 2017. Two gas pipelines operate from Iran to Iraq: one to Baghdad and the second to Basra. Iraq also imports electricity from Iran. The electricity imports are subject to U.S. sanctions and require a waiver, which the Trump administration continues to provide.

Iran’s gas supplies to Iraq have been erratic, however. There have also been frequent price disputes between the two countries. In 2018, Iran even cut supply to Iraq, leading to extensive electricity outages. Even without such disruptions, Iraq’s electricity provision is uneven and is subject to frequent blackouts. Power outages have triggered anti-government demonstrations in Iraq.

Source: Majed al-Suwailem, Saleh al-Muhanna, and Rami Shabaneh, “U.S.-Iran Tensions and the Waiver Renewal for Iranian Gas Exports to Iraq,” King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center, January 30, 2020, page 4. (https://www.kapsarc.org/research/publications/u-s-iran-tensions-and-the-waiver-renewal-for-iranian-gas-exports-to-iraq/)

Armenia

Iran initiated gas exports to neighboring Armenia in 2009. Armenia pays for this gas by exporting electricity to Iran. Armenia currently imports approximately 0.5 bcm of natural gas annually from Iran, but the pipeline between the two countries, owned by Gazprom’s Armenian subsidiary, can carry more gas. Both Armenia and Iran have expressed interest in using more of this spare capacity and establishing additional pipelines.

In fact, Tehran and Yerevan would like Armenia to serve as a transit state for Iranian gas exports to new destinations. Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan stated so during his visit to Iran in February 2019. Of particular interest to Armenia and Iran is a gas export route running from Armenia to Georgia and on to destinations in Europe.

Armenia has announced that it will not comply with U.S. sanctions on Iran, and Tehran frequently praises this defiance. As the Tehran Times recently noted, “The northwestern neighbor Armenia is one of the countries preserving and expanding its economic relations with Iran regardless of the sanction condition.”

Since Armenia exports goods as payment for gas imports from Iran, these transactions are sanctionable. It is not clear why the Trump administration has not applied sanctions to these transactions.

Implications of Ending Gas Imports From Iran

All three states that import gas from Iran have supply options to replace the Iranian gas or produce energy from different fuel sources. Turkey has already made a significant shift in its gas import mix, increasing LNG imports and pipeline gas volumes from Azerbaijan and decreasing imports from Iran and Russia. The fact that Ankara did not rush to repair the recently attacked gas pipeline from Iran illustrates that these supplies are not critical for Turkey, especially under the current economic conditions.

For Iraq, halting gas imports from Iran could further disrupt the country’s unstable electricity supplies. However, Iraq could replace its gas with oil, since its electric power plants have dual-fuel capability. Over 60 percent of Iraq’s electricity is currently generated from liquid fuels (diesel, crude oil, and heavy fuel oil). Plummeting oil demand has left surplus oil available for this purpose. This would yield important geopolitical benefits by reducing Iraqi dependence on Iran. Indeed, this is the time for the Trump administration to encourage Iraq to make this transition, using the renewal of electricity waivers as leverage.

Ending imports of Iranian gas might also incentivize Iraq to take steps to capture its gas rather than flare it. This would yield environmental as well as long-term economic and geopolitical benefits. Flaring is a significant contributor to air pollution and climate change. Baghdad has committed to reduce flaring but has so far failed to do so.

Armenia could end gas imports from Iran without major consequences. The country uses Iranian gas to produce heat, but that heat could be generated by the electricity Armenia currently exports to Iran. Additional electricity could be produced by building a low-cost, coal-fired plant, which could be built quite quickly.

Ceasing electricity exports to Iran would have an additional benefit. These exports currently rely on the Metsamor nuclear power plant, which is a danger both to the people of Armenia and the wider region. This Soviet-era nuclear power plant has no secondary containment structure and is located in a major seismic zone. One-quarter of the electricity produced in this plant is exported to Iran in exchange for natural gas. Ending these electricity exports to Iran would enable Yerevan to close the plant, which would remove a danger to Armenia and its neighbors.

Conclusion

Washington still has not used all the sanctions tools at its disposal to maximize the pressure on Tehran. Iranian natural gas exports are a prime target. The United States should encourage Turkey, Armenia, and Iraq to end imports of Iranian natural gas. For all three countries, the risk of doing so is low, while the potential long-run economic and geopolitical benefits are great.

Brenda Shaffer is a senior advisor for energy at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD) and an adjunct professor at Georgetown University. She also contributes to FDD’s Center on Economic and Financial Power (CEFP). For more analysis from Brenda and CEFP, please subscribe HERE. Follow Brenda on Twitter @ProfBShaffer. Follow FDD on Twitter @FDD and @FDD_CEFP. FDD is a Washington, DC-based, nonpartisan research institute focusing on national security and foreign policy.