April 21, 2020 | Policy Brief

COVID-19 and the Economy in Regime-Held Syria

April 21, 2020 | Policy Brief

COVID-19 and the Economy in Regime-Held Syria

The pandemic has worsened the currency crisis and inflation that have afflicted Syria since the economy in next-door Lebanon began to collapse last September. The cash-strapped regime of Bashar-al Assad has almost no ability to cushion this blow with stimulus spending or other relief measures.

Situation Overview

One year ago, the Syrian pound traded at less than 600 to the dollar, whereas it now hovers around 1,300. The pound had been stable for three years following the Russian military intervention that saved the Assad regime, although the currency never recovered its pre-war value.

While U.S. and EU sanctions cut off much of the regime’s access to hard currency, Lebanon remained a critical source of supply, thanks to its dollarized economy. Yet after more than 20 years of pegging its currency to the dollar, the Lebanese government became so mired in debt that it could no longer maintain the peg. Banks responded with strict limits on withdrawals, which affected both Lebanese depositors and the many Syrians who rely on Lebanese banks for both personal and commercial transactions.

Imports have become progressively more expensive in Syria as the value of the pound has fallen, since importers must pay for their purchases in hard currency. The Assad regime sought to ease the pain for consumers by raising government salaries, pensions, and the minimum wage, but the increases were too small to make much of a difference.

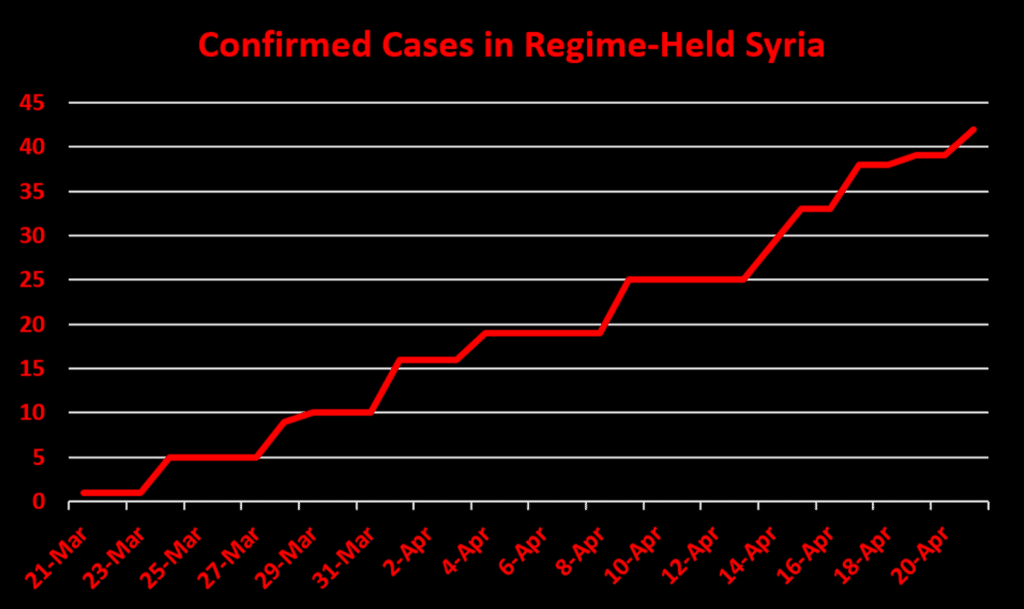

In mid-March, the regime began to implement mandatory social distancing measures, including school and business closures, foreign and domestic travel bans, and a 6pm-to-6am national curfew. The Ministry of Health acknowledges only 42 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including three deaths, yet there are numerous indications of a systematic cover-up.

After hovering between 1,000 and 1,100 pounds to the dollar since early January, the exchange rate shot up within days to 1,300 per dollar after social distancing measures took effect. There are no rigorous measures of inflation, but local media reported increases of 40 to 75 percent in the price of groceries. The price of medical goods and sanitizers rose even more sharply. Lockdowns in neighboring counties have also disrupted the flow of remittances from Syrians abroad, a major source of hard currency for both private individuals and the regime, which claims a sizable share of any funds repatriated through formal channels.

COVID-19 in the Greater Middle East

| Country | Cases | Deaths |

| Turkey | 95,591 | 2,259 |

| Iran | 84,802 | 5,297 |

| Israel | 13,942 | 184 |

| Saudi Arabia | 11,631 | 109 |

| Pakistan | 9,565 | 201 |

| UAE | 7,755 | 46 |

| Qatar | 6,533 | 9 |

| Egypt | 3,490 | 264 |

| Morocco | 3,209 | 145 |

| Algeria | 2,811 | 392 |

| Kuwait | 2,080 | 11 |

| Bahrain | 1,973 | 7 |

| Iraq | 1,602 | 83 |

| Oman | 1,508 | 8 |

| Afghanistan | 1,092 | 36 |

| Tunisia | 884 | 38 |

| Lebanon | 677 | 21 |

| W. Bank & Gaza | 466 | 4 |

| Jordan | 428 | 7 |

| Somalia | 286 | 8 |

| Sudan | 107 | 12 |

| Libya | 51 | 1 |

| Syria | 42 | 3 |

| Yemen | 1 | 0 |

Source: JHU Coronavirus Resource Center

Data current as of 4:00 PM, April 21, 2020.

Implications

With the economy already in dire straits, the cost of social distancing measures is difficult to bear. Business leaders close to the regime are already pushing for a partial reopening of the economy, and the cabinet has lifted a handful of restrictions. Yet relaxing too many could bring on precisely the kind of massive outbreak that would overwhelm the regime’s debilitated health-care system.

The Syrian finance minister announced that the government would spend 100 billion pounds to fight the pandemic, although this only amounts to $75 to $80 million, or about $5 per person. This sum is likely an indication of just how little the regime has left in reserve, not counting the private wealth that Assad and his inner circle have stashed away.

Finally, Damascus has escalated its calls for a suspension of U.S. and EU sanctions on humanitarian grounds. However, the credibility of the regime’s concern for its citizens is limited, especially following UN reports earlier this month that confirmed its use of chemical weapons and deliberate bombing of civilian targets, including hospitals.

What to Watch for

The greatest risk for the Syrian economy is an outbreak like the one in Iran, where the regime’s initial cover-up contributed to a nationwide epidemic whose scale made it impossible to deny. While the World Health Organization should be pressing for greater transparency, its Syrian office defers almost entirely to the regime, much like other UN aid providers.

An accelerated outbreak could potentially destabilize the regime, yet Assad has survived extraordinary threats to his grip on power.

David Adesnik is director of research and a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), where he also contributes to FDD’s Center on Economic and Financial Power (CEFP). For more analysis from David and CEFP, please subscribe HERE. Follow David on Twitter @adesnik. Follow FDD on Twitter @FDD and @FDD_CEFP. FDD is a Washington, DC-based, nonpartisan research institute focusing on national security and foreign policy.