February 27, 2020 | Monograph

Torture TV

The Case for Sanctions on the Islamic Republic of Iran’s State-Run Media

Contents

February 27, 2020 | Monograph

Torture TV

The Case for Sanctions on the Islamic Republic of Iran’s State-Run Media

Executive Summary

The Islamic Republic of Iran has a long history of using threats, physical torture, or psychological duress to coerce its political opponents into admitting guilt, even when they have not committed a crime. Though forced confessions violate international law, they are common tools used by the Islamic Republic. The regime broadcasts these false confessions on national television or the internet to frame the innocent, scare its citizens into submission, and propagandize against its enemies.

The regime’s preferred vehicle for airing forced confessions is Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB). IRIB is Tehran’s state-run media corporation with a near-monopoly on all television and radio services. The length interrogators go to elicit these false confessions on camera illustrates how much the regime values these videos in its broader disinformation campaigns.

To coerce political prisoners into appearing on camera and falsely admitting to contrived crimes, interrogators often beat prisoners with cables, sometimes to the point of paralysis; hold prisoners in solitary confinement for years; or threaten forced injections of hallucinogenic drugs.1 On occasion, the reporters on state-run news broadcasts are actually the interrogators who extracted the forced confessions.2

In using forced confessions, Iranian state media violate human rights of the innocent, demonize minority groups, delegitimize dissidents, and frame dual-nationals for contrived crimes. IRIB’s role in the Islamic Republic’s practice of extracting forced confessions should earn the media outlet sanctions worldwide. Targets should also include IRIB’s leadership and the state-run media agencies controlled by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Sanctioning these individuals and entities could squeeze IRIB’s $750 million annual budget and deter forced confessions. In so doing, sanctions could hamper the regime’s ability to project its narrative to audiences within and beyond Iran’s borders.

Imposing sanctions on IRIB, its leadership, and other facilitators of forced confessions would follow an established precedent. The European Union, Canada, and the United States have all previously designated Iranian individuals and entities responsible for forced confessions.3

However, IRIB’s leadership has changed since these designations. Since 2016, only the United States has sanctioned IRIB Director General Abdulali Ali-Asgari. He and other officials continue to work with the clerical regime’s judicial system and intelligence community to extract and broadcast false confessions. Moreover, the IRGC has built its own news agencies that also broadcast forced confessions. With new officials and agencies abusing human rights, action is needed.

While the United States maintains sanctions on IRIB itself, Washington has waived these sanctions every six months since 2013. The State Department has indicated that in exchange for waiving sanctions on IRIB, the Iranian government promised to cease the blocking of international frequencies, a technique known as orbital jamming.4 Iran has violated this agreement. In November 2019, Iran International Television, a Persian-language news channel based in London, submitted a complaint to the United Kingdom’s communications regulatory body, citing Iranian orbital jamming of HotBird and ArabSat satellites.5

Despite these violations, confidential commitments between Washington and Tehran have kept the IRIB waivers in place. Though they may inhibit Washington from implementing sanctions on IRIB, there are other actions the United States and other countries can take to ensure IRIB’s officials are held accountable.

Illustrations by Daniel Ackerman/FDD

Introduction

The Islamic Republic of Iran has a long record of extracting and broadcasting forced confessions by innocent political prisoners. Forced, false confessions are flagrant violations of international conventions, including the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.6 Moreover, many countries, including Iran, have adopted their own laws that prohibit forced confessions (see Appendix 1). Though the constitution and penal code of the Islamic Republic both forbid torture and forced confessions, Iran’s theocracy routinely disregards these prohibitions.7

Nevertheless, the regime does not try to conceal its use of coerced confessions. Amid the nationwide protests that broke out in November 2019, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani publicly called for the “confessions of the rioters,” adding that “these people must be dealt with.”8 Abdolreza Rahmani Fazli, Iran’s interior minister, appeared on IRIB’s Channel One to announce the regime’s intent to force detained protestors to confess on IRIB programs. “Now that the key people are being arrested … their confessions must be broadcast on television,” he said.9 In late December 2019, IRIB aired a pseudo-documentary titled The Truth of the Story, which included forced confessions in which imprisoned protesters falsely claimed that they were influenced by foreign actors, armed, and intending to kill security forces.10 Only one Kurdish protestor, Fatemah Davand, was named in the program. The film portrayed Davand, a mother of three, as the leader of the anti-government “riots.”11

This report presents nine case studies of forced confessions aired on IRIB channels, all but one of which occurred after Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, appointed Abdulali Ali-Asgari as the director general of IRIB in May 2016. The victims remain imprisoned, have been executed, or were released after paying bail often set at hundreds of thousands of dollars. Each case study provides background on the victims and describes the broadcasts themselves. This report also includes one case study of a political prisoner who so far has evaded IRIB’s cameras but whose experience provides key insights into the regime’s efforts to extract forced confessions.

The number of victims since 2016 is not limited to the cases studies in this report. However, these case studies capture a representative sample of the regime’s targets: dual nationals, non-citizens, members of religious minority groups, and political activists.

The exact number of victims remains unknown for three primary reasons. First, not all false confessions are broadcast on Iranian television or uploaded to the internet. Sometimes, forced confessions are extracted and preserved for later use, especially when the courts cannot present real, incriminating evidence against the framed defendant.12

Second, some broadcasts are aired once during primetime but are not uploaded to video-sharing sites on Iran’s national intranet, such as Aparat, and therefore are inaccessible online.13 Even if broadcasts are uploaded to Iran’s intranet or shown multiple times on state television, IRIB producers sometimes blur faces and do not reveal the names of the victims.14

Third, there is no database of IRIB broadcasts comparable to Nexis or Westlaw, which provide comprehensive and reliable access to content from Western media organizations. To identify subjects for its case studies, this report relied on human rights organizations, family members of the victims, and where possible, the accounts of those who were able to withstand the pressure to falsely confess and later described their mistreatment publicly. In several instances, human rights organizations have published the names of additional victims of coerced confessions, but there is little further information available on these cases.

Human rights organizations have identified three individuals by name – Maedeh Hojabri, Fatemah Davand, and Ruhollah Zam – as victims of forced confessions. The lack of open source information regarding these cases precludes this report from analyzing the circumstance of their imprisonment and forced confessions.15

While human rights organizations have published accounts of forced confessions, this report provides a comprehensive study of this sordid practice under IRIB’s current leadership. This report draws from both English- and Persian-language news outlets, published testimonies of detained and freed prisoners, IRIB pseudo-documentaries about prisoners, and video files of forced confessions that reveal the name and face of the victim.

In each of the false confessions detailed in this report, Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence (MOI), the IRGC, and Iran’s judicial system all played a role.16 However, the Islamic regime’s state media are an integral part of the regime’s torture and human-rights-violating machinery. No effort to stop torture would be comprehensive if it neglected IRIB and related outlets. Indeed, IRIB is the only media group with access to political prisoners in detention, while human rights organizations are denied the same access.

Forced confessions follow a common blueprint. Even if a prisoner does not give explicitly self-incriminating testimony, IRIB producers edit and manipulate the testimony to fit the regime’s intended narrative. For example, IRIB producers add voiceovers over footage of prisoners speaking, giving the false impression that the prisoner is speaking in the voiceover.

The films also exploit social norms and taboos, such as adultery, drug use, or divorce, to further demonize the victim.17 IRIB, and the regime more broadly, attempt to tie prisoners to the foreign powers the regime frequently vilifies, principally the United States and Israel. This aligns with IRIB’s pattern of vilifying the “great Satan” and “little Satan” in television, radio, and written reporting.

The evidence against IRIB is overwhelming. It is therefore not surprising that the United States, European Union, and Canada have all previously sanctioned IRIB or its leadership for its use of forced confessions. These designations should now serve as the legal basis for further action against organizations and individuals tied to IRIB.

Overview of Iranian State Media: Structure, Purpose, and Crimes

Structure

In 1971, the Pahlavi government established a state-run broadcasting organization called National Iranian Radio and Television (NIRT), which merged National Iranian Television and Radio Iran. Following the Islamic Revolution in 1979, NIRT was transformed into the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB).18

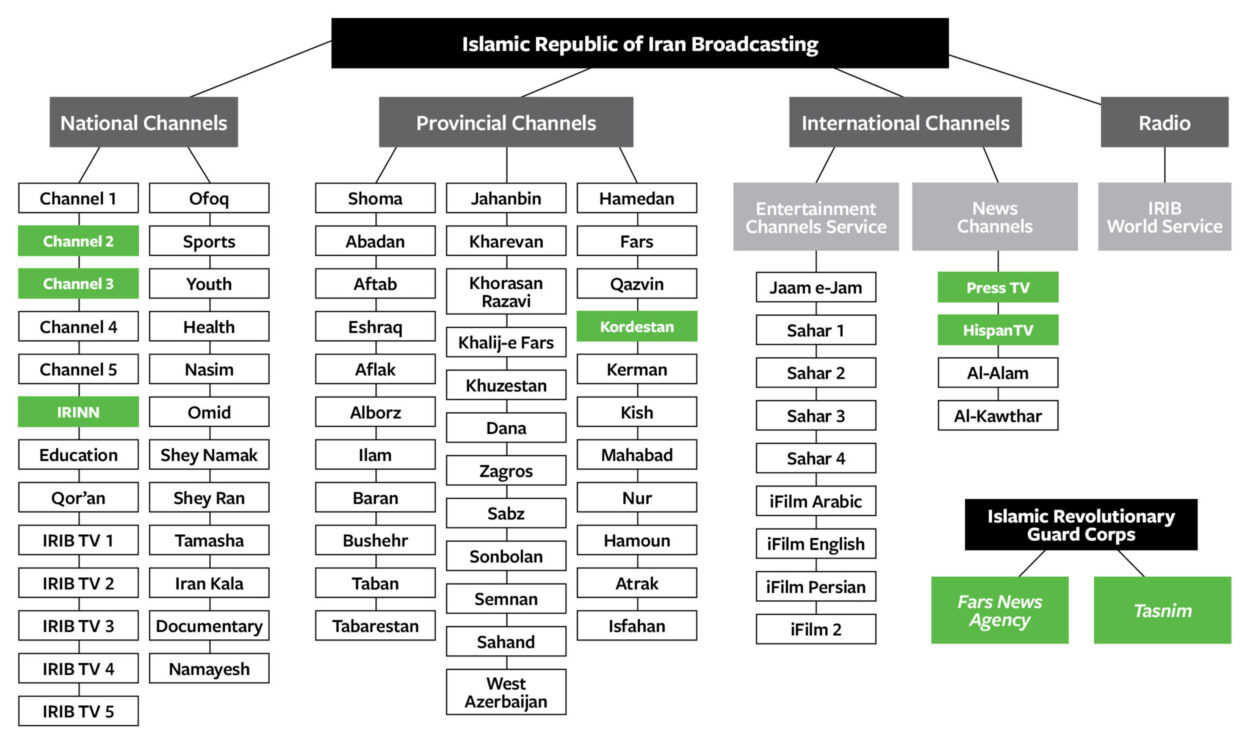

IRIB is the regime’s state-run media corporation, headquartered in Tehran. It serves as the primary propaganda organ of the clerical regime and is charged with burnishing the regime’s reputation. IRIB seeks to transform its audience at home and abroad into regime sympathizers. Iran’s constitution prohibits private broadcast media, thus granting IRIB a near-monopoly over radio and television services in Iran.19 However, IRGC-linked news agencies, such as Tasnim and Fars News, operate print and wire services.

Iran’s theocratic constitution grants the supreme leader the power to appoint the head of IRIB, thereby giving the organization a hardline ideological bent. In 2017, the Iranian government set IRIB’s annual budget at nearly 30 trillion rials (approximately $750 million) to operate its more than 50,000 employees worldwide.20

IRIB operates 20 national television channels and 34 provincial channels. It also runs 13 international television channels, including four news channels that cater to non-Farsi speakers. These include Press TV, IRIB’s English-language news channel; HispanTV, a Spanish-language news channel; Al Alam, an Arabic-language news channel; and Al-Kawthar, an Arabic-language religious channel with news bulletins throughout the day.21 As of February 5, 2020, three satellite companies – EutelSat, IntelSat, and ArabSat – broadcast IRIB programs to audiences in the Middle East, Central Asia, and Europe, though the total number of satellites that broadcast IRIB fluctuates.22 IRIB World Service also controls dozens of radio stations, more than 30 of which are internationally accessible.23

Across radio and television, IRIB broadcasts in 27 languages, including French, Russian, Hebrew, and German.24 IRIB and its affiliates have large budgets and offices in 20 countries, including: the United States (in New York, accredited to the United Nations), the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Russia, Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Lebanon, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, South Africa, Syria, Malaysia, India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, China, Belgium, Egypt, and Japan.25

An organizational chart of IRIB stations. Channels in green broadcasted the forced confessions cited in this report.

In addition to IRIB, other state-run newswires participate in the regime’s disinformation campaigns and broadcast show trials and forced confessions. These newswires include Tasnim and Fars News.

Tasnim, launched in 2012 and controlled by the IRGC, not only publishes false confessions by protesters on its website and social media, but also posts pictures of protestors on social media and asks readers to help identify them.26

Fars News is an IRGC-affiliated wire service launched in 2003 that produces articles and videos in Farsi, Arabic, Turkish, and English.27 Like Tasnim, Fars News is not under the IRIB chain of command but is nevertheless a state-controlled news agency. In 2007, the Iranian news site Tabnak revealed that the IRGC funds Fars News. Hamidreza Moghadamfar, the CEO of Fars News from 2007 to 2011, was the IRGC’s former director of cultural-social affairs. After working at Fars News, Moghadamfar became an advisor to the commander of the IRGC and rose to the rank of second brigadier general.28 Moghadamfar’s successor, Seyyed Nizam-al-Din Mousavi, was formerly the head of the political office of the Basij Student Organization at the University of Tehran. The Basij is an IRGC-linked paramilitary force. Under Mousavi, Fars News launched a campaign to investigate IRGC rivals and actively recruited Iranian celebrities, such as Iranian singer Amir Tataloo, to support the IRGC. Payam Tirandaz, a veteran of the Basij, became the CEO of Fars News in 2017, replacing Mousavi.29

According to Saeed Ghasseminejad, senior advisor on Iran at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, every individual who has held a leadership position in Fars News has been a member of the IRGC.30

Purpose and Methods

To enforce IRIB’s near-monopoly, the regime limits the use of private satellites and international frequencies. In 1994, the Iranian government passed a law that banned the private ownership of satellite technology and tasked police with confiscating satellite equipment.31 The regime regularly dispatches the Basij militia to confiscate and destroy satellites and receivers.32

IRIB’s international television programs portray the Islamic Republic as a moderate and tolerant country. Female anchors wear vibrant clothes and makeup, programs feature upbeat music, and men and women cordially participate together in roundtable discussions about politics.33 These programs obfuscate or ignore the Islamic Republic’s suppression of women and minorities and its aggressive rejection of Western culture. IRIB’s careful disguise of the oppressive nature of Iran’s autocratic regime is a key part of IRIB’s overall objective of winning supporters.

IRIB’s coverage during the 2009 Green Revolution illustrates how state media seek to deceive their audience. The Green Revolution began when Iranians took to the streets to protest the regime’s manipulation of the presidential election in favor of the incumbent, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. During these mass demonstrations, members of the Basij fatally shot Neda Agha-Soltan, a 26-year-old philosophy student, as she was walking back to her car.34 A video of her gruesome death went viral, stirring international outrage.35

To quell the outrage, IRIB aired a pseudo-documentary on January 5, 2010, on Press TV, claiming Neda was a spy for the United States and the United Kingdom. The film alleged that the viral video of her death was a lie. The narrator claimed that Neda poured a bottle of blood on her face, and her supposed pro-Western collaborators, not the Basij, shot her from behind.36

IRIB also vilified the protestors by broadcasting show trials. One of these televised trials included more than 100 defendants.37 State-run media, including IRIB and IRGC news wires, clearly coordinated with the regime’s judiciary to paint the defendants as criminals. Indeed, less than 30 minutes after the prosecutor read his opening statement, Fars News published the entire indictment. The indictment was also virtually identical to an article published in the regime-controlled newspaper Kayhan.38 Ayatollah Khameini characterized the forced confessions, including that of Maziar Bahari, as “legal testimony that is religiously justified.”39

The regime also uses IRIB to wage campaigns against minority groups within Iran. In July 2019, for example, BBC News reported that Twitter suspended accounts run by the Young Journalists Club, an IRIB affiliate, and Islamic Republic News Agency, a state-run wire service, for “coordinated and targeted harassment of people associated with Baha’i.” The regime regularly targets the Baha’i religious minority, restricting their access to education, due process, and other freedoms.40

IRIB also facilitates some of the regime’s spy missions outside of Iran. One prominent example is the case of Marzieh Hashemi. An American-born and U.S.-based reporter for Press TV, Hashemi helped Monica Witt, a former sergeant and counterintelligence specialist in the U.S. Air Force, defect to Iran. Witt went on to work with the IRGC and divulged sensitive counterintelligence information. Witt’s criminal indictment stated that Hashemi, labeled “Individual A,” was a reporter working in the United States for Iranian intelligence.41 The FBI detained Hashemi for ten days on a material-witness warrant. She was released on January 24, 2019, after she testified. Hashemi then returned to Tehran, where she continues to work for Press TV.42 Her testimony has not been made public.

Iranian State Media and Forced Confessions

According to historian Ervand Abrahamian, the Shah’s government began using forced confessions just prior to the Iranian Revolution in 1979. After the revolution, forced confessions became commonplace.43

In June 1981, the Islamist regime targeted the Mujahedin-e Khalq (MEK), then a militant opposition group. This was a notable period of repression and executions known as the “Reign of Terror,” though many dissidents had been summarily executed as early as 1979. Although the MEK opposed the Islamist regime with violence, the regime also targeted peaceful objectors. From June 1981 to June 1988, the regime executed thousands of Marxists, Kurds, MEK members, and others Tehran deemed dangerous. Execution methods included firing squads and hangings. Others died by torture.44

To facilitate this crackdown, the Islamic Republic established a new judicial system and interrogation protocol. The regime centralized and expanded the prison system while establishing new laws that gave seminary-trained interrogators a license to torture. Specifically, the landmark bill “Qanon-e Ta’zir,” or Discretionary Punishment Law, permitted interrogators to give an indefinite number of lashes to prisoners who “lie to authorities.” This law allowed interrogators to beat prisoners as punishment for unsatisfactory answers, whether true or false.

The Islamic Republic’s first supreme leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, viewed confessions “as the highest proof of guilt.” This, coupled with the new laws, laid the foundation for the systematic use of forced confessions across the regime’s institutions.45

The mass executions of the summer of 1988 marked an intensification in the Islamist regime’s immoral treatment of prisoners and reliance on forced confessions. On July 19, 1988, Iran’s main prisons shut themselves off from the outside world. Guards prohibited phone calls, cleared prisons of all radios and televisions, and cancelled scheduled visits. Khomeini issued an order to establish commissions to interrogate and order executions of leftists and anyone associated with the MEK. When brought before these commissions, suspects were asked whether they were willing to denounce their former colleagues and beliefs before a camera. If the prisoners gave unsatisfactory answers, they would be immediately blindfolded, led to the gallows, and hanged.46

For the victims’ families, broadcasts of forced confessions are often the last time they see their loved ones alive. For fellow prisoners, these broadcasts serve as a means of intimidation. Nizar Zakka, a former political prisoner in Iran, explained at a United States Senate Human Rights Caucus panel in December 2019 that prisoners are forced to gather and watch these broadcasts. This both humiliates the prisoner who falsely confesses and convinces others that resistance is futile.47

Remarkably, Iran’s own constitution and penal code prohibit torture, especially when used to extract a confession (see Appendix 1). Yet today, the Islamist regime routinely uses these practices. In 2019, Mahmoud Sadeghi, a parliamentarian in Iran’s Majlis, proposed a bill that would explicitly criminalize broadcasts of forced confessions.48 If passed, violators of this law would face jail time. As of February 5, 2020, only 70 of 290 Majlis members have signed the bill, which has yet to move out of parliamentary commissions for deliberation.49

Even if the bill garners enough votes, it will almost certainly not reach the president’s desk. Iran’s Guardian Council, an unelected 12-member body appointed by the regime, screens all legislation for loyalty to the regime’s ideology and may veto any bill it wishes.50 Because the supreme leader has expressed an affinity for forced confessions, the bill is unlikely to advance.

Forced, false confessions continue to play a role in the regime’s messaging to its domestic opponents. Nationwide protests erupted after Tehran announced a spike of at least 50 percent in fuel prices on November 15, 2019. On December 23, Reuters reported that the regime’s violent suppression of the protests killed over 1,500 demonstrators.51

Less than two weeks later, Abdolreza Rahmani Fazli, Iran’s Interior Minister, appeared on IRIB’s Channel One claiming that the protestors collaborated with foreign governments. He announced, “Now that the key people are being arrested … their confessions must be broadcast on television.”52 Soon after, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani announced that IRIB would air even more “confessions of the rioters … in the future, and you will see they have been planning for more than two years.”53

As recently as December, IRIB broadcast arrested demonstrators falsely admitting to being instructed and paid by foreign countries.54 These videos portray both adults and minors making forced confessions to crimes against the regime.55 Subsequently, on December 18, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution calling on the Iranian government to end its human rights violations, especially its crackdown on protestors. The resolution specifically condemned forced confessions and their role in the regime’s judicial system.56

Forced Confessions: Case Studies

The following case studies detail eight examples of forced confessions elicited after Abdulali Ali-Asgari became director general of IRIB in May 2016, and one that occurred prior to Ali-Asgari’s appointment. Although the regime has subjected many other Iranians to coerced confessions since 2016, these particular cases offer representative examples of the regime’s targets and of IRIB’s strategies and tactics.

The first eight case studies are organized chronologically, according to when IRIB aired each one. Three case studies involve forced, false confessions by members of minority religious and ethnic groups; these examples demonstrate how IRIB demonizes entire minority communities by exploiting selected scapegoats. Three other cases illustrate how the regime vilifies the United States, Israel, and other countries by targeting dual-nationals and presenting them as spies. One case exemplifies the regime’s treatment of political prisoners who are outspoken about their abuse in prison. Another case involves two participants in White Wednesday, a movement critical of compulsory hijabs, whose personal lives were exploited on Iranian television.

The final study illuminates the brutal treatment of Iran’s prisoners in detention, and outlines why Ottawa, in particular, should take action against the regime in support of Canada’s own permanent resident.

| Name | Date of Arrest(s) | Date False Confession Aired | Status (As of February 12, 2020) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kaveh (Abubakr) Sharifi | September 24, 2009 | August 3, 2016 | Executed |

| Xiyue Wang | August 7, 2016 | November 25, 2017 | Released in prisoner exchange |

| Ahmadreza Djalali | April 24, 2016 | December 17, 2017 | Sentenced to death |

| Mohammad Salas Babajani | February 19, 2018 | February 19, 2018 | Executed |

| Houshmand Alipour | August 3, 2018 | August 9, 2019 | Sentenced to death |

| Mohammad Ostadghader | August 3, 2018 | August 9, 2019 | Sentenced to 11 years |

| Niloufar Bayani | January 24, 2018 | -- | Sentenced to 6–10 years |

| Esmail Bakhshi | November 18, 2018 • January 20, 2019 | January 19, 2019 | Released on bail |

| Sepideh Gholian | November 18, 2018 • October 26, 2019 • November 16, 2019 | January 19, 2019 | Released on bail |

| Mariam and Martin Amiri | Date unknown | August 22, 2019 | Sentenced to 15 years |

| Saeed Malekpour | October 4, 2008 | Date unknown | Escaped back to Canada |

Kaveh (Abubakr) Sharifi

Kaveh Sharifi, also known as Abubakr, was a religious Sunni Kurd living in the Golshan neighborhood of Sanandaj, one of the capitals of Iran’s Kurdistan province.57 In 2007, Shiite preachers began making defamatory statements about Sunnis. In response, Sunni youth from Kurdish provinces held classes to raise awareness and defend their religious beliefs. They also distributed books and CDs that documented anti-Sunni rhetoric.

This campaign grew, and between 2009 and 2011, intelligence officials cracked down on the Sunni Kurdish minority. Amidst armed confrontations and assassinations, members of the regime’s intelligence apparatus arrested hundreds of Sunni men in Kurdistan Province, accusing them of being extremists associated with al-Qaeda, ISIS, and the like, though no evidence supported this.

On September 24, 2009, while Sharifi was walking from his sister’s home to a mosque for morning prayers, agents of the Sanandaj Information Administration blindfolded and arrested him.58 Four months later, his family learned of his incarceration, and in late January 2010, they visited him at the Sanandaj Information Administration detention center. In an interview with the Abdorrahmen Boroumand Foundation, a trusted source revealed that he was held by his arms during the visit because he could not walk; the guards had beaten the soles of his feet. He endured severe torture while in detention, causing frequent internal bleeding in his stomach.59

Over the next four years, Sharifi was denied access to an attorney, seldom saw his family, was transferred to two other prisons, and was frequently held in solitary confinement.60

Along with other Sunni detainees, Sharifi secretly recorded himself inside prison on a mobile phone and posted the recording to social media. He reported that MOI officials ordered him to memorize six pages of text containing his forced confession. “They even told me how I should move my hands and keep a happy face so that no one would suspect I was held in solitary confinement or ill-treated,” he said. Sharifi confessed to crimes he never committed, both during off-camera interrogations and on-camera interviews.61

Nearly five years after his arrest, Sharifi and four others stood trial in Branch 28 of the Tehran Revolutionary Court, presided by Judge Mohammad Moghisseh. They were charged with the crime of “waging war against God.” Sharifi faced the additional charge of “possession of a firearm and participation in the attack against the Revolutionary Guards military base.” They were accused of being members of a fictitious extremist group called Towhid and Jihad (“Unity and Jihad”), which the MOI had fabricated after the Sunni Kurds’ arrests in 2009.

According to the Kurdistan Province Judiciary, the forced confessions from the interrogations and interviews were used as evidence. The trial, which lasted less than 10 minutes, concluded with a death sentence for all five defendants. On February 1, 2014, Branch 32 of Iran’s Supreme Court upheld the death sentences.

On August 2, 2016, while Sharifi was still hospitalized from a heart attack he suffered the day prior, he was taken to a solitary confinement cell. A day later, Sharifi and 24 others accused of being members of Towhid and Jihad were hanged at Raja’i Shahr Prison.62

On the day of the executions, IRIB’s Kurdistan Province branch broadcast Sharifi’s and other Sunni Kurds’ coerced confessions in a five-part program called Terror and Takfir.63

In part one, the program identified Sharifi as the commander of Towhid and Jihad. In his false confession, Sharifi recited the six pages of text MOI officials instructed him to memorize. He was also forced to say that Towhid and Jihad falsely blamed the Iranian government for Sunni casualties of the group’s terror operations.

In part two, Sharifi discussed purported plans to assassinate a Shiite judge, again from a text prepared by his captors. In part five, Sharifi explained his fake group’s philosophy. He said all who oppose the group, including ordinary people, are considered infidels and targets of its terror operations.64

In a November 2016 press release, Amnesty International said, “By parading death row prisoners on national TV, the authorities are blatantly attempting to convince the public of their ‘guilt,’ but they cannot mask the disturbing truth that the executed men were convicted of vague and broadly defined offences and sentenced to death after grossly unfair trials.”65

Screenshots from the IRIB program Terror and Takfir. The caption says the clip is of Sharifi addressing a group of Kurdish university students.

Xiyue Wang

Xiyue Wang is a Chinese-born naturalized citizen of the United States and a Ph.D. candidate at Princeton University. His doctoral studies focused on local governance in Persia from 1880 to 1921.

Wang sought to travel to Iran to study Farsi and bolster his research with primary source documents. In 2016, Wang secured authorization from both Princeton University and the regime to travel to the country twice. He was granted a student visa by the Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. On May 1, 2016, Wang arrived in Iran for his second trip to continue his research. In July 2016, while Wang was sifting through historical, unclassified documents with no relevance to Iranian national security, the Iranian Diplomatic Police, a branch of Iran’s national police, summoned him for questioning and interrogated him for four hours without a lawyer present.66

On August 7, 2016, the Diplomatic Police arrested Wang at his apartment and sent him to Evin Prison. Wang was held in solitary confinement for 18 days and had no access to a lawyer until September 13. Five months later, Branch 15 of the Revolutionary Court officially charged Wang with espionage and collaborating with the “hostile State” (that is, the United States).67 On April 29, 2017, the Revolutionary Court found Wang guilty and sentenced him to 10 years in prison. Wang’s lawyer filed an appeal, but on August 14, 2017, Branch 54 of the Revolutionary Court denied it.68

Wang described to his family how he suffered in prison. Wang revealed to them that he lost weight and suffered from “chest pain, severe back pain, fever, rash, headaches, vomiting, stomach aches, severe tooth pain, foot injuries, arthritis, constipation, insomnia, and diarrhea.” He told his family that he did not see sunlight for weeks at a time and frequently battled suicidal thoughts and depression.69

After solitary confinement, Wang was placed in a series of dirty and overcrowded cells where he had to sleep on a 20-square-meter floor with up to 25 other prisoners. Some of his cellmates were members of the Taliban, who beat and threatened to kill him. Despite numerous requests from the Swiss Embassy and Wang’s lawyer in Iran, Wang was denied medical treatment outside of the prison.70

In November 2017, IRIB Channel 2 ran a six-minute program on Wang that included his forced confession.71 Asma Jahangir, then the UN special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Iran, confirmed that “a State television channel aired an apparent ‘confession’ which is understood to have been coerced.”72 Wang joins Washington Post reporter Jason Rezaian and freelance journalist Roxana Saberi on the list of American citizens the Islamic regime has imprisoned and forced to falsely confess – Saberi in 2009 and Rezaian in 2014.73

Wang spoke English when he appeared on the program. He did not say anything explicitly self-incriminating; rather, he only described his academic work and its importance. The producers used bits and pieces of this interview, often cutting his sentences short and then filling in the blanks themselves to paint Wang as a CIA agent. His sentence fragments were interspersed with pictures of the CIA seal and footage of Princeton students walking across campus as “ominous music suggesting villainy thrummed in the background,” The Washington Post reported.74

On December 7, 2019, Tehran released Wang from prison as part of a prisoner exchange with the United States. He returned safely to his family.75

Screenshots from IRIB TV2’s program on Xiyue Wang (top), which attempts to paint Wang as a CIA opperative.

Ahmadreza Djalali

Ahmadreza Djalali is an Iranian-born physician specializing in emergency medicine. Djalali lived in Sweden and lectured at the Karolinska Institute, a medical university from which he received a Ph.D. in disaster medicine.76

In April 2016, when he travelled to Iran at the invitation of the University of Tehran to lecture on disaster relief, agents of Iran’s MOI arrested Djalali.77 The regime accused Djalali of collaborating with Israel between 2010 and 2012 to assassinate Iranian nuclear scientists.78 The then-prosecutor of Tehran, Abbas Jafari Dolatabadi, charged Djalali with “collaborating with a hostile government,” claiming Djalali sent the Mossad names and information on more than 30 Iranian nuclear and military scientists.

Without evidence, Dolatabadi alleged that the information enabled the murders of two Iranian nuclear scientists in 2010, Massoud Ali Mohammadi and Majid Shahriari.79

After his arrest, Djalali spent three months in solitary confinement and seven months without access to a lawyer. On October 21, 2017, Branch 15 of the Revolutionary Court in Tehran found Djalali guilty and sentenced him to death. The Iranian Ministry of Justice’s news outlet, Mizan Online, labeled him a “Mossad agent.”80 On December 5, 2017, the Supreme Court upheld Djalali’s death sentence.

On December 17, 2017, Djalali’s forced confession aired on Islamic Republic of Iran News Network (IRINN), an IRIB news program based in Tehran.81 In a 17-minute pseudo-documentary called Axed from the Roots, Djalali told a false story about meeting “Thomas,” a supposed Mossad agent who introduced himself as an employee of a European company that later hired Djalali. The narrator said that “Mossad agents” including “Thomas” asked Djalali to divulge information on Iran’s nuclear program and its scientists.

Under duress, Djalali continued to tell the false story, describing the protocol for his meetings with Mossad agents, and the documentary purported to show footage of one of these meetings. The narrator claimed that Djalali met with these “agents” more than 50 times and expected citizenship in an unspecified Western European country as a reward.82

In December 2017, Djalali’s wife, Vida Mehrannia, who lives in Sweden with their two children, told the New York-based Center for Human Rights in Iran:

After being held in solitary confinement for the first three months of his detention, they threatened to kill his kids in Sweden and let him die in prison without telling anyone if he didn’t cooperate… It’s obvious from the video that Ahmadreza is not acting normal. At the time, he was under so much psychological pressure that he was given pills. That’s why he slurred his words in some places and was told to repeat his sentences. This interview was recorded under pressure and was not aired in full.83

That same month, BBC Persian aired an audio file released by Djalali’s in which Djalali denied the forced confessions and explained that he was recorded in prison while his psychological condition was poor. He also said he was promised freedom in exchange for falsely confessing on camera.84 In an undated letter sent from Evin Prison, Djalali wrote that the real reason for his incarceration was his refusal to spy for the MOI.85

The UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights repeatedly called on Iran to annul Djalali’s death sentence and allow him a fair trial “in line with international standards.”86 On February 17, 2018, the Swedish government granted Djalali citizenship in an effort to improve the chances of his release.87

Last year, Amnesty International issued an open letter to the prosecutor general of Tehran, Ali Alghasi Mehr, describing Djalali’s poor physical condition. He had lost 53 pounds and had a low white blood cell count. The letter called on the regime to provide Djalali with appropriate medical care.88

Authorities transferred Djalali from Evin Prison to an undisclosed location on July 29, 2019. As of February 5, 2020, he remains on death row.89

Screenshot of Ahmadreza Djalali making a forced confession in the IRIB-produced Axed from the Roots (left). An undated photo of Djalali from prison (right).90

Mohammad Salas Babajani

Sufi Gonabandi dervishes are followers of Shiite Islam and a religious minority in Iran. Dervishes describe themselves as rejecters of violence, politics, and wealth; they aspire to promote austerity, peace, and equality. They believe that through mystical practices and adherence to Sharia, they can achieve truth and a connection with God.91

Since Mahmoud Ahmadinejad became president of Iran in 2005, the Islamist regime has routinely arrested Sufi Gonabandi dervishes and targeted their homes and places of worship.92 The regime has sentenced dervishes to lashes, prison, and exile.93

In February 2018, amidst fears that the Basij militia would arrest their spiritual leader, Noor Ali Tabandeh, Gonabandi dervishes surrounded his home in Tehran to protect him.94 On February 19, riot police and members of the Basij confronted the dervishes, arresting more than 300 and injuring dozens.95 During these confrontations, a bus struck and killed three members of the Basij militia.96

The individuals the Basij arrested included Mohammad Salas Babajani.97 Hours later, while lying on a hospital bed, still in pain from head injuries sustained during his arrest, Salas was forced to falsely confess to driving the bus that killed the Basij members.98

Salas described himself becoming angry and losing control in a moment of passion. “I give my condolences,” he said. “What’s happened has happened. I’m going to be executed; what can I do? I’ve got two kids. I’ve my whole life to be successful. Let them execute me: what can I do?”

This forced confession was uploaded to Iran’s domestic video-sharing service, Aparat, by what appears to be a third party unaffiliated with the Islamist regime.99 Though Aparat is not officially affiliated with IRIB, the regime plays a role in monitoring the site and censoring any content deemed illegal.100

In March 2018, Branch 9 of Tehran’s Province Criminal Court One tried Salas for the killings. Salas’ false confession was the only evidence discussed in court. At his final court session, presided by Mohammadi Kashkuli, Salas finally had an attorney of his choosing. He retracted his forced confessions and explained that he was coerced into making them. He stressed that he was apprehended by the Basij before the bus collision and therefore could not have been the assailant.101

The court did not summon witnesses prepared to corroborate Salas’ claims. Though Salas’ lawyer, Zeynab Taheri, told the judge she had new, exculpatory evidence, the judge did not order an investigation into this evidence. No forensic investigation was conducted into the fingerprints on the steering wheel of the bus, even though doing so would have exonerated Salas.102

On March 19, 2018, Branch 9 of Tehran Province Criminal Court One sentenced Salas to one year in prison, 74 lashes, and death. On April 15, 2018, Branch 39 of the Supreme Court upheld this sentence, and the head of Iran’s judiciary confirmed this decision.103

Salas’ lawyer released an audio on May 22, 2018, in which Salas denied killing anyone, saying, “I was not the driver of the bus that killed those people. I am not a killer. I cannot even kill an ant… The police have fabricated all of this.”104

On June 18, 2018, a video featuring Salas titled The Face of Justice was archived on Mizan Online, the news outlet of Iran’s Ministry of Justice.105 In it, Salas falsely confessed in court that he drove the bus and cedes a history of drug abuse and disturbing public order.

The video also showed family members of the three dead Basij members in court asking for a death sentence. The narrator claimed Salas said in court he was in love with the idea of execution and that the deaths of the three Basij members were the will of God. The video, however, did not provide evidence of Salas making these comments. At its conclusion, the documentary portrayed foreign-based human rights organizations and media as having misrepresented the case. The film did not mention any organizations by name.

After The Face of Justice aired, Salas’ daughter told Oslo-based Iran Human Rights (IHR), “He was tortured before and after the arrest. They broke his finger after the first trial when he denied the allegations of deliberately killing police officers.”106

Salas was hanged on June 18, 2018, at Raja’i Shahr Prison, in the city of Karaj.107

Screenshots of Salas’ forced confession uploaded to Aparat, extracted hours after his arrest on February 19, 2018.

Screenshot from The Face of Justice. Here, the video includes footage from one of Salas’ earlier court appearances, during which he delivered a false, coerced confession.

Houshmand Alipour and Mohammad Ostadghader

Houshmand Alipour and Mohammad Ostadghader are Iranian-Kurdish friends from northwest Iran near the Iraqi border. Alipour is from Sardasht, while Ostadghader lives in Saqqez.108 Alipour’s family cedes that both Alipour and Ostadghader are members of the Kurdish Freedom Party (PAK) but do not participate in the party’s violent activities. Rather, the family says, the two raise awareness about PAK among Iranian Kurds and engage in strictly political activities.109 There is no independent verification of this claim.

Alipour and Ostadghader were arrested on August 3, 2018, in connection with an attack on a police station in Saqqez earlier that day.110 Ostadghader was shot in the leg during his arrest. He did not receive any medical care for his injury. On August 9, PAK issued a statement claiming responsibility for that attack, noting that Alipour and Ostadghader did not take part. Rather, PAK sent them to the scene to rescue injured PAK members. Upon doing so, the two were arrested.111

On August 9, Akam News, an MOI-affiliated outlet, reported that a Kurdish “terrorist team” had been apprehended. The article included a video of Alipour and Ostadghader falsely confessing to committing previous crimes and intending to commit more.112

The two men were forced to say on camera that the United States lied about training Kurds to fight the Islamic State, when it actually trained them to commit acts of terror within Iran.113 No evidence besides this forced confession suggests Iran was the focus of this training.

On the same day as the publication of the Akam News article, the video-sharing site Aparat uploaded another video featuring Alipour and Ostadghader.114 Their faces are blurred, the audio does not correspond with the video, and the rhythm of their voices suggests they likely read from a written statement. The audio playing over the footage said Alipour went to Saqquez as part of a team with orders from PAK to strike a security facility. When Ostadghader appeared on screen, the audio alleged he targeted intelligence personnel with grenades and firearms. It is not clear in either case whether the voice is that of the victim or of an IRIB narrator.

Alipour’s father told IHR he had not been permitted to communicate with his son in detention. However, Houshmand Alipour was able to briefly speak with Hejar Alipour, his brother, while detained at the Intelligence Office in Sanandaj.

“Under torture,” Hejar wrote in an open letter to human rights groups, “they have been forced to falsely implicate themselves, thus validating national security charges being levied against them… The extraction of confessions under violent torture, the broadcasting of those confessions[,] … the refusal to allow contact with attorneys or families, and denying visitation, are all violations of the basic rights of any prisoner … set forth by the Islamic Republic.”115

Hossein Ahmadniaz, the lawyer slated to represent the pair in court, told IHR on August 27, 2018, that Alipour and Ostadghader’s cases were tried at the Third Investigate Branch of the Saqqez County Court. Ahmadniaz said they had been charged with “war against God,” a crime punishable by death.116 Reports from April 15, 2019, indicate that their cases were referred from Branch 2 of the Prosecutor’s Office to Branch 1 of the Revolutionary Court, both located in Sanandaj. The courts relied on their forced confessions to determine their sentences.117

On December 30, 2019, the Revolutionary Court in Sanandaj sentenced Alipour to death, plus 16 years in prison.118 On January 23, 2020, a report emerged that the same court sentenced Ostadghader to 11 years in prison.119

Screenshots of Alipour (left) and Ostadghader (right) falsely confessing in a video produced by IRIB and posted to Aparat.

Niloufar Bayani

Born and raised in Tehran, Niloufar Bayani earned degrees in biology and conservation from McGill University and Columbia University. She later joined the UN Environment Program (UNEP) in Geneva.

In the summer of 2017, Bayani returned to Iran as a program manager for the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation (PWHF), an Iranian non-governmental organization. Eight PWHF colleagues traveled to Iran with Bayani.120

Since its founding in 2008, PWHF had worked with Iran’s Department of the Environment. Representatives of the PWHF traveled to Iran to track the Asiatic Cheetah, an endangered species, using wildlife camera traps.

On January 24, 2018, agents of the Intelligence Organization of the IRGC arrested Niloufar and her colleagues.121 The IRGC accused them of using their camera traps to record classified military information. It alleged they posed as conservationists to cover for espionage activity on behalf of the United States and Israel.122

PWHF’s managing director, Kavous Seyed-Emami, a professor with Canadian citizenship, died in Evin Prison on February 9, 2018, two weeks after his arrest. Tehran’s prosecutor general claimed that Seyed-Emami committed suicide, but his colleagues and family reject this claim. Days later, IRIB’s 20:30 news program aired a video smearing Seyed-Emami as a spy for the United States and Israel.123 Seyed-Emami’s son, Ramin, revealed that IRIB journalist Ali Rezvani coerced Seyed-Emami’s wife to speak out against her husband for the program.124

On July 31, 2018, the families of the eight remaining conservationists wrote an open letter stating that their loved ones were held in Evin Prison without access to counsel. The letter called on parliamentarians to visit the prison to hear their side of the story.125

When family members visited Evin, they noticed the prisoners had broken teeth, scars on their faces, and bruises all over their bodies.126 The Center for Human Rights in Iran also revealed that Bayani and her colleagues “were subjected to months of solitary confinement and psychological torture, threatened with death, threatened with being injected with hallucinogenic drugs, threatened with arrest and the death of family members.”127

In September 2018, IRIB attempted to frame Bayani by airing a pseudo-documentary about her, staging her supposed crimes. An anonymous source informed IHR that “plainclothes officers” took Bayani from Evin Prison to film her in various places around Tehran. They brought her to a beauty salon and offered her a haircut, then took her to a shopping mall in Lavason and encouraged her to “go on a shopping spree.” The anonymous source said that Bayani realized the strangeness of the circumstances and therefore “refused to leave the car.” The source also reported, “Upon needing to use the bathroom after several hours, [Bayani] noticed that one of the plainclothes officers was filming her every move from behind a tree. She immediately retreated to the car.”128

On October 24, 2018, Tehran’s then-prosecutor Abbas Jafari Dolatabadi formally charged Bayani and three others with “sowing corruption on Earth,” an indictment that could carry the death penalty.129 The other four conservationists face lesser charges, including espionage and “collusion against national security.130

At risk of additional torture, Bayani, who was denied a lawyer of her choosing, repeatedly interrupted the first day of her trial in Tehran on January 30, 2019. As Judge Abolghassem Salavati of Branch 15 of the Revolutionary Court read the 300-page indictment, Bayani announced that the forced confession, which was the only evidence cited in her indictment, was made under physical and psychological duress. IRIB has not yet aired Bayani’s forced confession and those of her fellow detainees. They purportedly made their forced confessions off- camera in Evin Prison, and IRGC agents who claimed to be witnesses relayed it to Tehran’s prosecutor.131

On February 2, 2019, the second day of her trial, Bayani continued to speak about her abuse. Bayani said in court, “If you were being threatened with a needle of hallucinogenic drugs [hovering] above your arm, you would also confess to whatever they wanted you to confess.”132

Some regime officials have denounced these indictments against Bayani and her colleagues and called for their immediate release. On May 22, 2018, the head of Iran’s Department of the Environment, Vice President Isa Kalantari, repudiated the IRGC’s allegations, stating, “[T]he detained activists should be released because there’s no evidence to prove the accusations leveled against these individuals.”133 Members of the Majlis also asked President Hassan Rouhani to ensure the defendants’ legal rights had not been compromised.134

The international community has also spoken up about the detainment and treatment of Bayani and her colleagues. In October 2018, the head of UNEP declared that the environmentalists “deserve the utmost support and fullest protection which Iran’s laws and constitution guarantee.”135 Two days later, the International Union for Conservation of Nature issued a formal statement denouncing the arrests and treatment of the conservationists and called for an independent investigation into the death of Seyed-Emami.136 In early November 2018, an open letter signed by more than 1,000 conservationists and environmentalists and addressed to Iran’s then-chief justice, Ayatollah Amoli Larijani, affirmed the eight detainees’ long history of professional environmental work and called for an equitable and fair judicial process.137

The regime’s persecution continues regardless. On November 6, 2019, the eight conservationists were accused of new charges. The regime alleged “cooperation with U.S. and Israeli enemy states against the Islamic Republic of Iran for the purpose of espionage for the CIA and Mossad.” Bayani and Morad Tahbaz were handed an additional charge of “gaining income through illegitimate means.”138

A few days later, IRIB Channel 3 broadcast another documentary about the conservationists, titled The Usual Suspects. The program abruptly stopped after just two minutes, with IRIB’s public relations office citing “technical issues.” Ramin Seyed-Emami identified the reporter who appeared in the first minute of the video as one of the IRGC agents who raided his father’s home after he died in Evin Prison.139

On November 20, 2019, without lawyers in the room, the Tehran Revolutionary Court sentenced Bayani and five others to six to 10 years in prison.140 UNEP subsequently issued a “call for clemency and urge[d] the Iranian authorities to review and overturn these sentences.”141

Undated headshot of Niloufar Bayani from the Scholars at Risk Network website.142

Esmail Bakhshi and Sepideh Gholian

Esmail Bakhshi and Sepideh Gholian are labor rights activists in Iran. Bakhshi worked at the Haft Tappeh Sugar Cane Company, located in Shush, Khuzestan. Gholian was a university student. After peacefully protesting Haft Tappeh’s unpaid wages outside the office of the governor of Khuzestan on November 18, 2018, the two activists were arrested. Both were coerced into confessing on tape. After a month in a MOI detention center without access to a lawyer, they were released on bail.

After their release, Bakhshi and Gholian accused security and intelligence agents of torturing them. Bakhshi published a letter on his Instagram page on January 4, 2019, and Gholian posted a video to social media in early January 2019.143 On January 14, 2019, Iran’s attorney general, Mohammed Jafar Montazari, claimed the torture accusations “were fundamentally lies and that there has been no beatings or torture.”144 Human Rights Watch declared that the regime “failed to conduct any credible investigations into the torture allegations.”145

On January 19, 2019, the forced confessions by Bakhshi and Gholian from November 2018 aired on IRIB Channel 2.146 The video is accessible on the website of Ensaf News, an opposition newspaper that appears in print and online.147 Their forced confessions were the subject of a segment titled The Burnt Plot.148 The watermarks on the video indicate it is an IRIB production. Among other things, the video aimed to discredit the Iranian labor rights movement as a foreign conspiracy connected to the United States and Israel. Esmail Bakhshi’s forced confession is specifically used to make this argument. Bakhshi was forced to falsely “admit” to working with other activists whom the documentary portrayed as radical leftists.149

Gholian’s forced confession appeared shortly after Bakhshi’s. She wore a conservative black chador, though her face was not blurred. She attributed her participation in the Haft Tappeh protests to her “Marxist political beliefs.” She said, likely under duress, that she prepared and sent a video to a friend in Turkey who worked for Amad News, an organization she described as seeking regime change in Iran. Amad News, founded by Iranian dissident Rouhallah Zam, is a news organization that reports on corruption and protests in Iran.150 At the end of her forced confession, Gholian also said she sent anti-regime materials to an individual affiliated with Tavaana, a civil society organization based in Washington, DC.151

A day after the IRIB broadcast, the two activists were arrested again.152 Amnesty International called for their release, characterizing the arrests as “part of a sinister attempt to silence and punish them for speaking out about the horrific abuse they suffered in custody.”153

Branch 28 of the Revolutionary Court of Tehran, presided by Judge Mohammad Moghiseh, conducted the trials of Bakhshi and Gholian in August 2019. Gholian and her attorney, Jamal Heydari Manesh, said her interrogators were abusive and coerced her into confessing in front of a camera. Judge Moghiseh nevertheless sentenced Bakhshi to 74 lashes and 14 years in prison on September 7, 2019. During a separate hearing on the same day, Gholian was sentenced to 18 years in prison. The charges against Bakhshi and Gholian include “assembly and collusion aimed to act against national security,” “propaganda against the state,” “spreading falsehoods,” and “insulting the Supreme Leader.”154

In a March 11, 2019, speech to the UN Human Rights Council, Javaid Rehman, the UN special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran, called attention to the “ill-treatment in detention” of Bakhshi and Gholian. He called on the regime to “release all those detained for exercising their rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, and association.”155

Gholian’s rapidly compromised health in prison left her bound to a wheelchair, unable to walk.156 On October 20, 2019, she began a hunger strike. Four days later, independent journalist Shahed Alavi released a recording of Gholian, who states, “My power to bear this is really faltering now… I just want a panel from the judiciary to come and see why it is that I can’t breathe. When my family just comes for a visit something awful happens to them and they’re told not to come again… I want people to know what awful things they’re doing to me in prison.”157

On October 25, Amnesty International released a letter demanding that Gholian and Bakhshi be released from prison, citing Gholian’s hunger strike and the audio recording.158 A day later, Gholian was released for around $120,000 in bail. 159 On October 30, Bakhshi was also released, on $70,000 bail.160

Gholian was arrested again on the evening of November 16, 2019, in her father’s home. Days before her arrest, an anonymous individual posted to social media a video of Gholian participating in the nationwide protests against the increase in fuel prices.161

On December 25, 2019, Gholian announced via Twitter that she was suing IRIB reporter Ameneh Sadat Zabihpour, who taped Gholian’s forced confession “after hours of physical and psychological torture.” Gholian detailed how Zabihpour gave her and Bakhshi a pre-written script for them to recite on camera. Gholian’s Twitter account was quickly deactivated. BBC Persian journalist Kasra Naji commented on Gholian’s tweets, adding that Zabihpour “doubles as interrogator and enforcer of forced confession in front of camera.”162

Gholian was later charged with “disseminating false claims” after tweeting about Zabihpour. On February 9, 2020, Gholian was released on a $43,000 bail.163

Screenshots from The Burnt Plot depicting the segments during which Esmail Bakhshi (bottom) and Sepideh Gholian (top) deliver their forced confessions.

Maryam and Matin Amiri

Maryam and Matin Amiri are twin sisters who participated in the “White Wednesday” movement, an online social media campaign against compulsory hijab laws in Iran. The movement was founded in May 2014 by Iranian-born journalist Masih Alinejad. Participating women post pictures or videos of themselves wearing a piece of white clothing, a white hijab, or no hijab at all, along with the hashtag #WhiteWednesday.164 Maryam and Matin participated in White Wednesday by recording a video of themselves, which Alinejad posted on August 25, 2019. Holding her camera in one hand, one of the Amiri sisters declares in the video, “Our right to freedom, right to choose what we can wear. We won’t let anyone violate our rights…We’ll do this so much that every day will be White Wednesday.”165

Maryam and Matin were arrested for recording themselves without wearing a hijab. The exact date of their arrests is unknown.

On August 22, 2019, Fars News released a 14-minute documentary about the Amiri sisters, titled For a Few Dollars.166 A copy of the broadcast was also uploaded to Aparat.167 In this segment, the two sisters falsely confessed and called themselves “naïve, dumb, and passive” and “of weak personality” for protesting hijab laws. Each sister was interviewed independently, though the interviewer is neither seen nor heard. They wore black chadors, and their faces were blurred. Likely under duress, the sisters claimed that the hijab itself did not bother them, but they were emulating “films of protestors” and indiscriminately copying “social media and satellite content.”

The film included audio communications between the Amiris and Alinejad. One sister falsely confessed that she was aware that collaborating with Alinejad was “contrary to [moral] values,” but said she did not know she was engaging in criminal behavior.

The segment also indicated that the sisters were both getting divorces and living alone.168 One of the sisters said she engaged in “illicit relations” outside of her marriage.

At the end of the documentary, white text on a black background appeared: “Any sort of collaboration or collusion with the enemies of the regime towards committing crimes against national or foreign security is criminalized.”169

On August 25, 2019, three days after Fars News posted the video, Alinejad announced on Twitter that Maryam and Matin were sentenced to 15 years in prison.170 Two days later, Alinejad tweeted in Farsi that the sisters “were in solitary confinement and under duress for forced confessions.”171 Their family and friends have not publicly commented on the arrest and prison sentences.

Screenshots from A Tale of Treason. The individuals on the top and bottom left are Maryam and Matin Amiri, and the uncensored photo on the bottom right is of Masih Alinejad.

Saeed Malekpour

Saeed Malekpour was born in Iran in 1975. In 2004, he and his then-wife, Farima Eftekhari, emigrated from Iran to Canada, where he worked as a web designer and computer programmer.172

Before traveling to Iran in 2008 to visit his gravely ill father, Malekpour was pursuing Canadian citizenship.173 He had successfully secured Canadian permanent residency, which officially protected him under Canada’s Charter of Rights (with a few exceptions, such as the right to vote).174

On October 4, 2008, Malekpour walked to a dentist appointment in Tehran.175 Claiming to be armed, a man who did not identify himself asked Malekpour for his ID. Malekpour promptly handed over his passport, which the unidentified man said was a fake. Agents of Iran’s MOI then grabbed Malekpour, blindfolded and handcuffed him, and shoved him into a car. Agents of the IRGC’s Intelligence Organization took Malekpour to Evin Prison and severely beat him for days.176

According to a report from the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, Malekpour was immediately subjected to solitary confinement and denied contact with the outside world. The brutal beatings continued. IRGC agents kicked him in the face and beat him with cables and batons, sometimes until he passed out. IRGC agents broke his jaw and knocked out his teeth. At one point, half of his body became paralyzed.

Malekpour also suffered a heart attack but was denied sufficient medical treatment. When he did arrive blindfolded at a hospital, the doctors simply told him to get more sleep; they did not treat his heart, paralysis, broken bones, or concussion symptoms.177

Malekpour later said IRGC agents threatened to arrest his wife. Fearing for her safety, Malekpour complied with his captors and made a false confession on camera, during which he said the United States and United Kingdom paid him to distribute pornography and corrupt Iranian internet users.

In August 2019, the UN Human Rights Council’s Working Group on Arbitrary Detention determined that “[t]he purpose of [Malekpour’s] torture was to force a false confession, which was used to convict Mr. Malekpour of a capital offense.”178 The regime did not deny that Saeed’s scripted, false confession on television was a result of “physical and psychological torture and ill-treatments.”179

Iranian authorities used his forced confession to justify his guilty verdicts and sentencing. The forced confession was the only piece of evidence presented during Malekpour’s first trial, in December 2010, and his retrial, in November 2011. Both resulted in a death sentence.180

In August 2013, following international condemnation, the courts commuted his death sentence to life imprisonment, claiming that Malekpour appeared remorseful.181 Six years later, Malekpour was granted a three-day furlough. Fearing the continuation of torture, he told his sister, Maryam, “I’d rather die than go back.”182

Maryam helped him escape. She worked with the Canada-based Raoul Wallenberg Center for Human Rights, headed by Irwin Cotler, to expedite Malekpour’s Canadian documents. Lying to his own mother and the Iranian government about traveling to northern Iran to visit family, Malekpour trekked over 1,200 miles alone with just a backpack and some cash. He successfully crossed into Turkey, where his sister was waiting for him.183

On August 2, 2019, they landed in Vancouver.184 A day later, Maryam Malekpour posted a video of herself and her brother with the caption, “The nightmare is finally over. He is back home and reunited with his sister. Thank you Canada for your leadership.”185

Malekpour finally received medical treatment for his decade of torture at the hands of the IRGC.186 He spoke publicly about his treatment in Iranian prisons and his daring escape to freedom. Though Malekpour’s story unfolded prior to the appointment of Abdulali Ali-Asgari in 2016, Malekpour is one of the few political prisoners who escaped from jail and was willing to divulge publicly the details of his experience.

Sadly, Canada has not held Iran accountable for Malekpour’s unjust arrest, torture, and prolonged imprisonment. The Canadian government expedited Malekpour’s papers to help him escape Iran and reenter Canada. Yet Canada has not sanctioned under its Global Magnitsky laws the individuals or entities responsible for his abuse or taken other legal measures against the regime.

Screenshot of a BBC Persian report from 2011 on Saeed Malekpour. The BBC program aired portions of Malekpour’s forced confession.187

Worldwide Designations of IRIB

Sanctions against IRIB and related institutions not only would send a message that the global community will hold IRIB accountable, but also would limit, though not end, the regime’s access to international audiences. Sanctions may force IRIB to cut its $750 million budget, close offices, and reduce its foreign operations. Moreover, designations challenge IRIB’s credibility and dissuade viewers and listeners abroad from trusting IRIB broadcasts.

Beyond designating just IRIB, sanctioning facilitators of forced confessions would restrict their ability to travel outside of Iran and could freeze their foreign bank accounts.188 Designations also limit their ability to obtain hardware, software, technical and financial assistance, and other equipment and services.189

Imposing sanctions on IRIB and its affiliates would also benefit the Iranian people. Nobel Peace Prize laureate Shirin Ebadi, an Iranian dissident and human rights lawyer whose own husband was a victim of forced confession in 2009, asserts that targeting IRIB would cripple Tehran’s ability to spread propaganda and attack or intimidate dissidents. She thus called on Western satellite providers to refuse to air IRIB channels outside of Iran’s borders.190 Ebadi has derided IRIB’s foreign broadcasts “that lure the … Syrian, Lebanese, or Yemeni youth” to support the Islamist regime in Iran.191

The forced confession of Maziar Bahari, an Iranian-Canadian journalist, largely catalyzed past designations of IRIB and IRIB officials. Bahari was arrested while covering mass protests for Newsweek. Bahari’s interrogator told him he planned to use “every tactic” until Bahari falsely confessed to espionage. Bahari ultimately spoke to IRIB reporters in front of cameras after his interrogator promised to free him from Evin Prison if he gave a false confession.

Press TV aired the resultant video of Bahari falsely confessing to spying for the United States and Israel. Despite the interrogator’s promise, Bahari continued to endure physical and psychological abuse. He eventually was freed on bail and fled Iran in October 2009.192

OfCom, the United Kingdom’s communications regulator, ruled in May 2011 that Press TV egregiously breached broadcasting standards in airing Bahari’s forced confession and thus had to pay a £100,000 fine and transfer editorial control from Tehran to its London branch.193 After Press TV refused to comply with the ruling, OfCom revoked Press TV’s UK broadcasting license.194

Soon after, in 2012 and 2013, the United States and European Union imposed a variety of sanctions on IRIB officials. The tables in this section outline past designations connected to IRIB.

Designation Status of Key Organizations

| Name | Designated by | Not designated by | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) | U.S. (2013), Canada (2016) | EU | Sanctions waived every 180 days |

| Ayandeh Bank | U.S. (2018) | Canada, EU | -- |

| Tasnim | -- | Canada, EU, U.S. | -- |

| Fars News | -- | Canada, EU, U.S. | -- |

IRIB

The United States designated IRIB as a human rights abuser with the passage of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2013. Section 1248 of the Iran Freedom and Counter-Proliferation Act (passed as part of the 2013 NDAA) states, “The Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting has contributed to the infringement of individuals’ human rights by broadcasting forced televised confession and show trials.”195

Per a 2013 agreement with the International Telecommunications Satellite Organization (ITSO), an intergovernmental body that governs satellite providers, the Obama administration waived these sanctions on February 14, 2014. 196 The State Department concurrently released a notice stating that waivers for IRIB sanctions hinge on Iran’s cessation of satellite jamming.197 Other parts of the ITSO agreement have not been made public; nevertheless, Washington has since waived sanctions against IRIB every 180 days.

Before 2013, the regime interfered with signals from Persian-language international news channels, such as Radio Zamaneh and Voice of America Persian News Network. By using a technique called uplink jamming, or orbital jamming, the Iranian regime would beam an overriding signal toward a satellite, affecting users across large swaths of Iranian territory.

Tehran has not honored this commitment. In November 2019, Iran International, a London-based Persian-language broadcaster, found that conflicting signals emanating from central Iran jammed international satellites.198 Still, the U.S. waivers continued.

On February 5, 2016, three weeks after “Implementation Day” of the Iran nuclear deal, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, Ottawa lifted select sanctions on Iran but added IRIB to Canada’s list of designated entities.199 Those on this list are subject to the Special Economic Measures Act (SEMA), subsections 4(1) to 4(3).200 However, SEMA sanctions are insufficient to address IRIB’s human rights abuses, as these sanctions are implemented only when a “grave breach of international peace and security has occurred.” This provision is both a high bar for human rights abusers to reach and makes it difficult for the Canadian government to designate specific individuals associated with IRIB.

Global Magnitsky sanctions, however, would name human rights abusers and implement visa bans and asset seizures.201 As of February 5, 2020, Canada does not broadcast IRIB channels.

The European Union has not sanctioned IRIB.

Ayandeh Bank

In November 2018, the United States sanctioned Ayandeh Bank pursuant to Executive Order 13846 for “having materially assisted, sponsored, or provided financial, material, or technological support for, or goods or services to or in support of, IRIB, Iran’s state-media apparatus that routinely broadcasts false news reports and propaganda, including forced confessions of political detainees.”202

Neither the European Union nor Canada has imposed sanctions on Ayandeh Bank as of February 5, 2020.

Designation Status of Key Individuals

| Name | Title | Designated by | Not designated by | IRIB Replacement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ezatollah Zarghami | Director general of IRIB (2004–2014) | EU (2012), U.S. (2013) | Canada | Replaced by Mohammad Sarafraz in 2014 |

| Mohammad Sarafraz | Head of IRIB World Service and Press TV; director general of IRIB (2014–2016) | EU (2013) | Canada, U.S. | Replaced by Abdulali Ali-Asgari in 2016 |

| Abdulali Ali-Asgari | Director general of IRIB (2016–present) | U.S. (2018) | Canada | -- |

| Hamid Reza Emadi | Senior producer and newsroom director of Press TV (2007–2016) | EU (2013) | Canada, U.S. | Replaced by Wahid Tahami in 2016 |

| Wahid Tahami | Newsroom director of Press TV (2016–present) | -- | Canada, EU, U.S. | -- |

| Peyman Jebelli | Head of IRIB World Service (2016–present) | -- | Canada, EU, U.S. | -- |

| Morteza Mirbagheri | Deputy chief of IRIB | -- | Canada, EU, U.S. | -- |

| Majid Gholizadeh | Chairman of Tasnim | -- | Canada, EU, U.S. | -- |

Ezatollah Zarghami, Director General of IRIB (2004–2014)

The European Union sanctioned then-IRIB Director General Ezatollah Zarghami on March 23, 2012. The designation stated, “[H]e is responsible for all programming decisions. IRIB has broadcast forced confessions of detainees and a series of ‘show trials’ in August 2009 and December 2011. These constitute a clear violation of international provisions on fair trial and the right to due process.”203

On January 6, 2013, the United States sanctioned Zarghami as well. Section 1248 of the Iran Freedom and Counter-Proliferation Act of 2012 designated Zarghami for “the infringement of individuals’ human rights by broadcasting forced televised confession and show trials.”204 The Treasury Department cited Maziar Bahari’s 2009 false confession as the basis for this designation.205 The aforementioned agreement with ITSO does not forbid sanctions on individuals working for IRIB, as opposed to the organization as a whole. Thus, the United States can maintain sanctions on IRIB officials should it choose to do so.206

Canada never designated Zarghami. Zarghami left his position in 2014.

Mohammad Sarafraz, Director General of IRIB (2014–2016)

In August 1994, Mohammad Sarafraz was appointed vice president of IRIB’s foreign service. In this position, he established Press TV and HispanTV.207 On March 12, 2013, while Sarafraz was the head of IRIB World Service and Press TV, the European Union designated him. Brussels cites as the basis for its designation Sarafraz’s work “with the Iranian security services and prosecutors to broadcast forced confessions of detainees, including that of Iranian-Canadian journalist and film-maker Maziar Bahari.” The EU designation concludes that “Sarafraz therefore is associated with violating the right to due process and fair trial.”208

In November 2014, Ayatollah Khamenei appointed Sarafraz to be director general of IRIB. The United States and Canada did not sanction him.

Sarafraz resigned in 2016.209

Abdulali Ali-Asgari, Director General of IRIB (2016–Present)

On May 30, 2018, the United States designated the current IRIB head, Abdulali Ali-Asgari, under Executive Order 13628. A press release from the U.S. Treasury Department states, “Abdulali Ali-Asgari … has acted on behalf of the organization, including representing the organization in international fora… IRIB was implicated in censoring multiple media outlets and airing forced confessions from political detainees.”210

No other country or international organization has designated him.

Hamid Reza Emadi, Senior Producer and Newsroom Director of Press TV (2007–2016)

The European Union sanctioned Hamid Reza Emadi on March 12, 2013. According to Maziar Bahari’s September 2012 testimony, Emadi interviewed him in Evin Prison and spoke with Bahari’s interrogator to draft language for his forced confession.211 The European Union designated Emadi for “producing and broadcasting the forced confessions of detainees, including journalists, political activists, persons belonging to Kurdish and Arab minorities,” thereby “violating internationally recognised rights to a fair trial and due process.” The designation further noted that Emadi is “associated with violating the rights to due process and fair trial.” In December 2015, the European Court of Justice rejected Emadi’s effort to challenge the designation.212

Neither the United States nor Canada designated Emadi.

Wahid Tahami replaced Emadi as the Press TV newsroom director in 2016, but no country has sanctioned Tahami as of February 5, 2020.

Policy Recommendations

The international community should stay committed to freedom of speech for reporters and news outlets. At the same time, journalists and media organizations who engage in forced false confessions cannot expect, and should not be granted, the same protections as independent news outlets that abide by international law.

IRIB and other state media masquerade as legitimate journalists and hide behind a corporate veil while violating international law by using physical and psychological torture to extract forced confessions from political prisoners.

The following are policy recommendations to address this problem:

1. For all countries:

- Sanction IRGC-controlled news wires Fars News and Tasnim for their roles in broadcasting forced confessions. They are not officially under the IRIB umbrella; therefore, the United States would not be violating its agreement with ITSO by designating these news wires.

- Sanction the following individuals, each of whom is involved in extracting, producing, or distributing forced confessions:

- Abdulali Ali-Asgari, director general of IRIB

- Wahid Tahami, newsroom director of Press TV

- Peyman Jebelli, head of IRIB World Service