December 5, 2019 | Monograph

Maximum Pressure 2.0

A Plan for North Korea

Executive Summary

North Korea’s nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons represent a grave threat to the United States and its allies. To convince North Korean leader Kim Jong Un to relinquish these weapons, the Trump administration initiated a “maximum pressure” campaign. This effort imposed significant economic costs on North Korea and incentivized Kim to come to the negotiating table. So far, however, this pressure has been insufficient to persuade him to denuclearize.

It is certainly possible that no level of pressure will persuade Kim to change course. But there is a need to test that proposition. The United States and its partners have not yet implemented a more aggressive and comprehensive maximum pressure campaign that targets Kim’s cost-benefit analysis. Such a campaign likely represents the only way to denuclearize North Korea without resorting to war.1

This monograph proposes that the United States, working with its allies and partners, implement a “Plan B” to drive Kim to relinquish his nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. Such a campaign must integrate all tools of national power, including diplomacy, military, cyber, sanctions, and information and influence activities.

Illustrations by Daniel Ackerman/FDD

After setting the scene in the introductory chapter, this study includes a dedicated chapter on each of the five lines of effort that together should constitute a “maximum pressure 2.0” campaign. Each chapter is written by experts at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and provides background, analysis, and specific recommendations.

In the chapter titled “Aggressive Diplomacy,” Mathew Ha, David Maxwell, and Bradley Bowman warn against falling prey again to the North Korean regime’s longstanding practice of diplomatic deception. The authors note that Pyongyang routinely makes provocations both to advance its nuclear and missile capabilities and to win valuable concessions through negotiations. They also note that Pyongyang has violated every agreement it has reached over the last 20 years. The authors caution against additional presidential-level summits. Instead, they encourage the United States to redouble its efforts to jumpstart substantive working-level dialogues that establish specific timetables for the inspection, dismantlement, and verification of each nuclear and missile facility. In order to build necessary unity with South Korea and Japan while shaming China and Russia for obstructionism, the authors emphasize the importance of a comprehensive public diplomacy campaign that provides America leverage in its standoff with Pyongyang.

In the chapter titled “Military Deterrence and Readiness,” David Maxwell, Bradley Bowman, and Mathew Ha emphasize the importance of South Korea-U.S. military readiness in deterring North Korean aggression, protecting U.S. interests, empowering effective diplomacy, and supporting a maximum pressure campaign. The authors note that the North Korean military threat has not decreased. They also note the assessment of the U.S. Department of Defense’s 2019 Missile Defense Review that North Korea has “neared the time when” it could “threaten the U.S. homeland with missile attack.” The authors propose several specific steps to strengthen allied military readiness, protect U.S. national security interests, and support a maximum pressure 2.0 campaign. In the end, they note, American power is what deters North Korea.

In the chapter titled “The Cyber Element,” Mathew Ha and Annie Fixler note that Pyongyang continues to employ an aggressive cyber campaign to generate revenue and conduct intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance. The authors call for a U.S.-led cyber-enabled information and offensive cyber campaign targeting North Korea. They propose specific cyber-related actions against China, Russia, and other countries to persuade them to dismantle North Korea’s cyber network. To help carry out these efforts, the authors call for the creation of a joint South Korea-U.S. cyber task force.

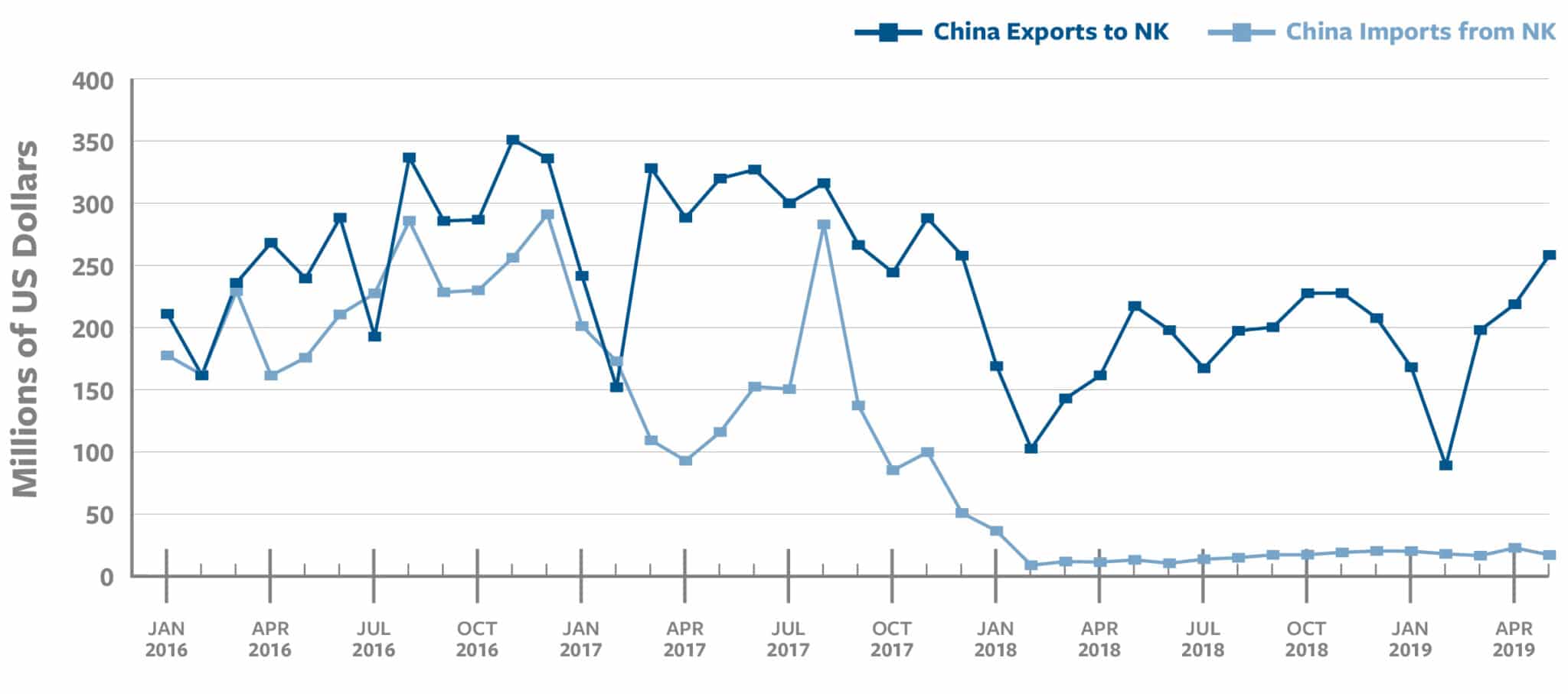

In the chapter titled “U.S. Sanctions Against North Korea,” David Asher and Eric Lorber detail the existing sanctions regime targeting North Korea. The authors describe Pyongyang’s efforts, working with Chinese entities and others, to circumvent these sanctions. The authors propose specific measures to increase the economic pressure on Pyongyang. Examples include revitalizing the North Korea Illicit Activities Initiative, designating the leadership of major Chinese banks that engage in prohibited transactions with North Korea, hardening small banks against North Korean sanctions evasion, and targeting joint ventures. In short, there is more room to squeeze the North Korean regime.

In the chapter titled “Information and Influence Activities,” David Maxwell and Mathew Ha argue that aggressive information and influence activities represent an essential component of a successful maximum pressure 2.0 campaign. The authors believe that external pressure alone is unlikely to persuade Kim to denuclearize. They recommend a number of specific information and influence activities targeting North Korea’s regime elite, second-tier leadership, and general population. These activities would seek to foster Kim’s perception that the security of his rule will continue to deteriorate until he decides to relinquish his nuclear weapons. Even if information and influence activities do not yield the desired outcome, these tools can prove useful in the event of renewed military conflict.

Maximum Pressure 2.0: A Plan B for North Korea

By David Maxwell and Bradley Bowman

Introduction

Former President Barack Obama advised then President-elect Donald Trump that North Korea would be his top national security challenge. The outgoing president’s warning was prescient. During President Trump’s first year in office, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) tested an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and a thermonuclear weapon.2 It was also a year of saber-rattling rhetoric between North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and Trump. This escalation follows a dangerous pattern that has prevailed for 25 years.3

On June 30, 2017, at a Republic of Korea (ROK)-U.S. summit, Trump and his South Korean counterpart, Moon Jae-in, agreed to pursue complete denuclearization of North Korea and a maximum pressure campaign to bring Pyongyang to the negotiating table. They also agreed that South Korea would take the lead in establishing conditions for peaceful intra-Korean unification.4 In the year that followed, the allies implemented a targeted pressure campaign – to which this monograph will refer as “maximum pressure 1.0” – that included strong UN and U.S. sanctions on key North Korean entities and certain Chinese banks and facilitators. This campaign also included aggressive measures against the North’s global illicit activities, an international diplomatic effort, and increased emphasis on the military deterrence capabilities of the ROK-U.S. alliance. This pressure campaign cannot truly be described as “maximum,” however, since it lacked a holistic approach incorporating diplomatic and military pressure, cyber actions, and information and influence activities.

Conditions appeared to change in 2018, beginning with a seemingly conciliatory New Year’s Day speech by Kim and an invitation from Moon for the North to participate in the upcoming Winter Olympics in South Korea.5 South Korean, North Korean, and American officials soon initiated discussions that culminated in three summits between Moon and Kim and a summit in Singapore between Trump and Kim. These engagements led to the so-called Panmunjom and Pyongyang Declarations, which included tension-reduction and confidence-building measures aimed at reducing the potential for military confrontation along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and in the East and West Seas. Seoul and Pyongyang codified these measures in a Comprehensive Military Agreement (CMA) in September 2018.6

U.S.-North Korean relations seemed to remain on a positive path during the beginning of 2019. A North Korean delegation visited the White House and scheduled a second Trump-Kim summit, which was eventually held in Hanoi in late February.7 However, Kim would not allow his negotiating team to discuss denuclearization, limiting talks to ancillary issues and summit preparations. At the summit, Kim demanded the removal of all sanctions imposed since March 2016, in return for closing North Korea’s Yongbyon nuclear facility – a demand unacceptable to Trump, who walked out of the negotiations.8

Kim’s failure to achieve substantial sanctions relief knocked him off balance. He almost certainly feels pressure from regime elites and the military to elicit additional concessions from the Trump administration. This perhaps explains a subsequent series of actions by Kim designed to enhance his legitimacy at home and coerce the United States into negotiations that would yield sanctions relief.

South Koreans at the Seoul Railway Station watch a television broadcast of a North Korean missile launch on October 31, 2019, amid stalled denuclearization talks with the United States and cooling inter-Korean ties. (Photo by Woohae Cho/Getty Images)

After Hanoi, the North began rehabilitating its Sohae missile launch facility,9 which Kim had promised at Singapore to dismantle. The DPRK military conducted exercises to demonstrate readiness and test-fired a new anti-tank guided missile system.10 Throughout the summer of 2019, the North tested a number of short-range ballistic missiles and multiple rocket launchers.11 There has been unusual training activity at the Yongbyon nuclear facility12 as well as reports of internal purges of North Korean officials associated with the nuclear negotiations.13 Finally, in an apparent attempt to shift blame for the Hanoi failure and separate Trump from his advisers, Pyongyang has spewed hostile rhetoric at the Trump administration – particularly Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and then-National Security Adviser John Bolton – while refraining from verbal attacks on the president himself.14

North-South military and diplomatic activities, meanwhile, have reached a standstill.15 Despite the easing of security procedures in the Joint Security Area and the destruction of a dozen guard posts, North Korea regularly skips scheduled liaison meetings at Kaesong.16 While Seoul has high hopes for the CMA, Pyongyang has demonstrated a lack of sincerity in implementing even basic confidence-building measures.

While the United States focuses its attention mostly on North Korea’s nuclear and missile capabilities, Pyongyang possesses other significant capabilities that threaten U.S. and allied interests. The Kim regime retains a formidable arsenal of chemical and biological weapons, and its conventional military threat to the South remains substantial.17 Pyongyang has also developed a sophisticated cyber capability to hack banks, steal funds, conduct espionage, and execute influence operations in South Korea.18 In addition, North Korea routinely conducts illicit fundraising activities.19

Finally, the Kim regime is one of the worst human rights abusers in the world. The 2014 UN Commission of Inquiry detailed the regime’s crimes against humanity and recommended Kim Jong Un for referral to the International Criminal Court.20 This was reaffirmed in a 17-page UN General Assembly report in August 2019.21

That same month, a UN Panel of Experts also published a report on DPRK sanctions evasion activities. The 142-page report outlined Pyongyang’s global illicit activities, its extensive use of cyber operations to raise funds, and the methods it employs to evade UN sanctions. The report also provides an extensive list of entities contributing to these efforts.22

In an interview with 38 North, the American member of the UN Panel of Experts highlighted Pyongyang’s cyber operations and its sanctions evasion activities:

In one notable example of the growing sophistication of the attacks, DPRK cyber actors gained access to the infrastructure managing entire ATM networks of a country in order to force 10,000 cash distributions to individuals across more than 20 countries in five hours…23

The UN Panel of Experts report makes clear that maximum pressure 1.0 has not achieved its goals.24 The campaign has not achieved the denuclearization of North Korea. It has also failed to prevent Kim from obtaining the resources necessary for continued development of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles, for support to his conventional military, and most importantly, for regime survival.

This monograph offers a “Plan B” to drive Kim to relinquish his nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. It is “maximum pressure 2.0.”25 We delineate five lines of effort: diplomacy, military, cyber, sanctions, and information and influence activities. It builds on and expands the work of the United Nations and the United States from 2017 to 2018.

Any effective approach toward North Korea should be based on two new assumptions. The first recognizes that Kim will give up his nuclear program only when he concludes that the cost to him and his regime is too great – that is, when he believes possession of nuclear weapons threatens his survival. But external pressure alone, although important, will almost certainly fail to create the right cost-benefit ratio. It is the threat from the North Korean people that is most likely to cause Kim to give up his nuclear weapons.26 As former CIA analyst Jung Pak of the Brookings Institution has argued, “Kim fears his people more than he fears the United States. The people are his most proximate threat to the regime.”27 The ROK-U.S. alliance has yet to adopt a strategy with this in mind.

U.S. President Donald Trump shakes hands with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un before a meeting in Hanoi on February 27, 2019. (Photo by Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images)

Kim, the DPRK military, and the North Korean elite must be made to recognize that keeping nuclear weapons poses an internal threat to their survival. External threats and actions alone will not suffice, though they are important. In addition, if these actors choose not to relinquish their nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons, a maximum pressure 2.0 campaign should threaten to weaken the regime.

The second new assumption is that Kim will continue to employ a strategy based on subversion of South Korea; coercion and extortion of the international community to gain political and economic concessions; and ultimately the use of force to unify the peninsula under the domination of the North, thereby ensuring the survival of the Kim family regime. A key element of his strategy is to drive a wedge between South Korea and the United States. Kim’s strategy can best be described as a “long con” whereby he extracts as much as possible for the regime while conceding little to nothing and preparing to achieve unification under his control. Kim is pursuing a strategy established long ago by his grandfather and improved by his father.

This assumption requires the United States and South Korea to prepare for the possibility that Kim might refuse to relinquish his weapons of mass destruction (WMD). This assumption is buttressed by a U.S. intelligence estimate maintaining that he is unlikely to denuclearize.28 This cannot be discounted and must be factored into a new strategy.

Plan B Overview

The proposed Plan B strategy consists of five elements: diplomatic, military, cyber, economic and financial sanctions, and information and influence activities.

The diplomatic component focuses on mobilizing the international community to adopt the maximum pressure 2.0 campaign and enforce domestic and international law to stop the regime’s illicit activities. Employing the U.S.-ROK strategy working group established in November 2018 will help the alliance prevent South Korean backsliding on the pressure campaign.29 While South Korea describes many of its projects in conjunction with the North as economic engagement activities, they are merely conduits for funds that flow directly to the Kim regime.

The military element rests on the military readiness of the ROK-U.S. alliance. Any reduction in the alliance’s combat readiness will reduce Kim’s incentive to negotiate and invite North Korean aggression. Accordingly, the United States and South Korea must engage in robust combined training and other military activities. These should include aggressive maritime intercept operations to combat ship-to-ship transfers that facilitate North Korean sanctions evasion and proliferation. Military training and exercises must be conducted without regard to Pyongyang’s propaganda. No matter how benign, ROK-U.S. military activities will always receive Northern criticism. Moreover, the suspension or cancellation of military activities has never elicited a good faith response from Pyongyang.

A more aggressive U.S. cyber campaign is necessary to combat the damage and illicit revenue generated by the North’s cyber activities. Cyber provides a critical asymmetric capability for the Kim regime. Pyongyang is pursuing new cyber techniques to support its efforts to steal hard and crypto currency and conduct espionage and influence operations. The United States and the international community must counter these threats.

The UN and U.S. sanctions regimes must be expanded and fully enforced, including by targeting non-North Korean entities, banks, and individuals that enable Pyongyang’s sanctions evasion activities. This must include enforcement of UN sanctions on North Korean overseas laborers. Likewise, the United States must intensify its scrutiny of North Korea’s shipping sector through monitoring and surveillance efforts in areas known for illicit ship-to-ship transfers.30 Sanctions must not be used as a bargaining chip. North Korea must comply with all UN and U.S. sanctions – by denuclearizing, terminating its missile programs, ceasing its illicit activities, and ending its human rights abuses – before they are lifted. Sanctions and enforcement must be incorporated into the diplomatic approach and coordinated with information and influence activities.

Robust information and influence activities must also be part of maximum pressure 2.0. The campaign must separate the Kim family regime from the second-tier leadership and general population. Achieving this goal could generate an internal threat that prompts Kim to give up his nuclear weapons. Providing the North Korean people with more outside information, including information related to the regime’s horrific human rights record, would undermine the legitimacy of the Kim regime.

The following five chapters provide a plan policymakers and strategists could implement to protect and advance U.S. interests on the Korean Peninsula. Following his failure at Hanoi, Kim gave an ultimatum to the United States, stating that by the end of 2019, Washington must “adopt a new posture” toward the North if denuclearization negotiations are to continue.31 It is therefore necessary to prepare for what may come next in 2020, while leaving open the possibility that Kim might adopt a less confrontational approach.

Maximum pressure 2.0 rests on a foundation of sustained pressure and military strength. This is necessary even as the United States continues to pursue working level negotiations that give Kim the opportunity to denuclearize. Should he not make the right strategic decision, the United States and its South Korean allies would then have in place the strategy and forces necessary to deter or defeat the North.

Aggressive Diplomacy

By Mathew Ha, David Maxwell, and Bradley Bowman

Background

The North Korean regime has mastered the art of diplomatic deception. It engages in provocations both to advance its nuclear and missile capabilities and to achieve valuable concessions. The regime calibrates its provocations to ensure they fall below the threshold that would elicit an armed response. Washington and its allies typically respond by offering diplomatic negotiations to address Pyongyang’s activities while avoiding military conflict.32 Once negotiations begin, North Korea avoids specific commitments or offers broad, ill-defined pledges they do not intend to honor.

Over the last 20 years, Pyongyang has violated every agreement it has reached with the international community regarding its nuclear weapons program. As a result, North Korea now possesses approximately 20 to 60 nuclear weapons and a formidable inventory of ballistic missiles capable of targeting South Korea, Japan, Guam, and the United States.33 General Terrence O’Shaughnessy, commander of U.S. Northern Command, testified in April 2019 that North Korea has flight-tested “multiple ICBMs capable of ranging the continental United States.”34

A survey of the diplomatic history between Pyongyang and the United States over the last few decades illustrates this strategy of deceit. After the United States withdrew all tactical nuclear weapons from South Korea as a good-will gesture in 1991, Pyongyang signed the 1992 Joint Declaration of the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.35 In the declaration, North Korea made an open-ended commitment not to “test, manufacture, produce, receive, possess, store, deploy or use nuclear weapons” and not to “possess nuclear reprocessing and uranium enrichment facilities.”36 Despite this pledge, North Korea produced enough plutonium to build two nuclear weapons.37

In the 1994 U.S.-DPRK Agreed Framework, the North agreed to implement the 1992 Joint Declaration and pursue nuclear energy for peaceful purposes. The new agreement required North Korea to freeze and eventually dismantle its graphite-moderated reactors.38 In exchange, an international consortium would provide two light water nuclear reactors, and the United States would provide annual shipments of 500,000 tons of heavy fuel oil. However, North Korea again violated the agreement by pursuing a uranium enrichment program.39

In 2005, the United States and North Korea held the so-called Six Party Talks with South Korea, Japan, China, and Russia. As a result of these talks, the North Koreans signed a joint statement in which they agreed to “abandoning all nuclear weapons and existing nuclear programs and returning, at an early date, to the treaty on the nonproliferation of nuclear weapons and to IAEA safeguards.”40 Once again, North Korea cheated, detonating its first nuclear device in 2006.

In February 2007, North Korea agreed to shut down and dismantle its Yongbyon nuclear facility within 60 days.41 The North Korean government destroyed the cooling tower at this facility in June 2008.42 In response, the United States returned all the funds it had previously seized from Banco Delta Asia (BDA)43 and removed North Korea from the State Sponsors of Terrorism list. Yet by 2008, North Korean restarted its nuclear facilities, expelled inspectors, and pocketed funds from U.S. concessions, refusing to agree to a verification protocol proposed by the United States. In 2010, North Korea revealed a new secret uranium enrichment facility.44

By 2009, the Six Party process was defunct. North Korea engaged in a series of provocations, including a nuclear test in May 2009, the continuation of its uranium enrichment program, and intra-Korean military skirmishes in 2010.45

South Korean Unification Minister Cho Myoung-gyun (2nd R) shakes hands with his North Korean counterpart, Ri Son Gwon (2nd L), on August 13, 2018, following talks in the village of Panmunjom, where the two sides agreed to hold an inter-Korean summit in Pyongyang in September 2018. (Photo by Hong Geum-pyo/KOREA POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

In 2017, the Trump administration implemented a maximum pressure campaign46 that integrated diplomatic and economic tools of national power.47 In 2018, in stark contrast with his biting rhetoric the previous year, Kim suggested that North Korea might want to participate in the Pyeongchang Olympics. This overture led to the first intra-Korean talks since 2012,48 culminating in an intra-Korean summit held in April and the Trump administration’s agreement to hold a bilateral summit.

Kim and Trump convened historic bilateral summits in Singapore and Hanoi on June 12, 2018,49 and February 27, 2019,50 respectively.51 At Singapore, Kim agreed to work toward the “complete denuclearization of the Korean peninsula” and to destroy a ballistic missile engine test site.52 Yet at the subsequent Hanoi summit, he refused to agree to a roadmap toward a final and fully verified denuclearization, leading Trump to walk away from the negotiations.53

Since Hanoi, Kim has increased his hostile rhetoric in an attempt to coerce the United States into lifting sanctions as a concession to restart talks. To demonstrate its discontent, Pyongyang conducted 12 missile tests: two in May of 2019 and 10 more between August and October of 2019.54 Trump downplayed the severity of these provocations, arguing that they were neither nuclear nor ICBM tests.55

But it is not that simple. So long as the Kim regime seeks to maintain or advance its nuclear weapon and ballistic missile programs, North Korea must conduct periodic tests. These tests help the regime advance its respective programs, and they also serve as important diplomatic signaling tools with which to extract concessions.

In June 2019, after a summit with Moon, Trump met Kim at the DMZ. After a brief hand-shaking ceremony, the two leaders shared a private discussion in the Inter-Korean House of Freedom.56 This meeting fueled expectations of a resurgence in Trump-Kim summitry. Some journalists have even speculated that the United States was seeking to fast-track negotiations by softening its negotiating position to require only a nuclear freeze.57 However, the U.S. government has denied this.

Assessment

The Trump administration deserves credit for making the North Korean nuclear and missile threats a sustained focus. Maximum pressure 1.0 undeniably squeezed the North Korean regime. Washington successfully encouraged more than 20 countries to curtail or end diplomatic ties with North Korea.58 Meanwhile, Trump’s unorthodox threats against North Korea almost certainly elevated the regime’s sense of insecurity. Simultaneously, the Trump administration imposed economic pressure on the Kim regime through U.S. sanctions and led a powerful multilateral sanctions campaign.59 Breaking with precedent, the administration also continued to impose new sanctions on North Korea even while engaging in diplomacy with Pyongyang.60

However, maximum pressure 1.0 has failed to achieve tangible progress toward the final and fully verifiable dismantlement of North Korea’s nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons programs. Not surprisingly, the absence of a substantive working-level dialogue has played a negative role in the failure of the summits in Singapore and Hanoi. Limiting substantive discussions on denuclearization to the leaders plays directly into North Korea’s hands. It is likely that Kim never intended to denuclearize. The Trump administration should have attempted to test Kim’s intentions at the working level before giving the North Korean despot the diplomatic benefit of a summit with the U.S. president.

Trump’s unpredictability, as well as his personal ambition to reach a grand bargain, may well lead him to make unnecessary – and even dangerous – concessions. Trump’s indefinite suspension of select ROK-U.S. military exercises during the Singapore summit is just one troubling example.

A maximum pressure 2.0 campaign may increase risk and tensions in the short and medium term, but it represents the best hope of denuclearization without war. The success of this campaign will depend on the administration’s ability to establish a shared consensus among key allies and partners on resolving the North Korea threat.

A screen projecting an image of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un (L) and South Korean President Moon Jae-in is seen during a ceremony on April 27, 2019, to mark the first anniversary of the Panmunjom declaration. (Photo by Lee Jin-Man/AFP via Getty Images)

While the Moon administration expresses strong support for North Korea’s final and fully verified denuclearization, Seoul appears to mistakenly believe concessions, rather than pressure, offer the best means of resolving the crisis.61 This could prove challenging for the maximum pressure 2.0 campaign.

History is replete with examples of the South undermining U.S. strategy. Former South Korean President Kim Dae-jung, for example, went as far as illegally paying $100 million to North Korea to hold the intra-Korean summit in 2000.62 In 2002, it became clear that Seoul’s inducement efforts failed when the world learned North Korea was covertly enriching uranium.63 Similarly, Washington’s decision to return North Korea’s frozen BDA assets in 2005 critically undermined U.S. diplomatic leverage over Pyongyang. The BDA freeze had deprived Pyongyang of funds and led other financial institutions to cut ties with North Korea, fearing penalization by the United States.64 Unfreezing these funds forfeited these benefits. In return, Pyongyang conceded nothing.

Maximum pressure 2.0 will succeed only if the United States and its allies, namely South Korea and Japan, are aligned.65 Unfortunately, throughout 2019, Seoul and Tokyo have engaged in an ugly dispute that has undermined their security cooperation. Despite initially impacting only their bilateral trade relations, this conflict culminated in Seoul’s decision in August 2019 not to renew its bilateral military information-sharing agreement with Japan. This decision, if upheld, would not only damage South Korea’s military-to-military cooperation with both Japan and the United States, but also would undercut South Korea’s own national security.66 North Korea, China, and Russia undoubtedly relish this friction, as they seek to drive a wedge between the United States, South Korea, and Japan.67 Washington should seek to address these divisions and encourage unity.

Japan’s priority is the denuclearization of North Korea. But Tokyo also believes that any comprehensive deal must address Pyongyang’s robust missile inventory – including missiles that can target Japan. Tokyo also seeks the return of Japanese citizens abducted by North Korean agents as far back as the 1970s.68

In addition to addressing the concerns of key allies, the United States must undertake an ambitious agenda at the UN Security Council (UNSC) to foster an international consensus for a second maximum pressure campaign. Admittedly, new international sanctions against North Korea will be difficult to attain, as Russia and China would likely use their vetoes at the UNSC. Beijing prioritizes stability on the Korean Peninsula, and the specter of crippling economic sanctions potentially destabilizing the Kim regime or sparking large-scale refugee flows into China evokes Beijing’s concern. Likewise, both China and Russia oppose the strong U.S. military presence in South Korea, and both hope to prevent the emergence of a unified Korea friendly to Washington.69

Recommendations

The United States led an impressive diplomatic effort to implement maximum pressure 1.0. While the campaign likely played a role in bringing Kim to the negotiating table, the negotiations have failed to achieve their objective. Consequently, Washington should lead a new maximum pressure campaign targeting North Korea. A key element of this campaign should be diplomatic and should include the following elements:

- Avoid premature presidential summits: Until Kim is ready to move toward denuclearization, additional presidential-level summits would almost certainly be futile and potentially even counterproductive. In fact, there should be no further summits at the presidential level until senior negotiators have agreed to major elements of an explicit and detailed roadmap with milestones for the dismantlement process, and until persistent North Korean cyberattacks against the United States and South Korea have ceased.

- Establish a substantive working-level dialogue between the United States and North Korea: The U.S. special representative should continue to insist on the establishment of a substantive working-level negotiating process. Specifically, the two sides should prioritize reaching a consensus regarding the definition of “verifiable dismantlement” of North Korea’s nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons and ballistic missiles. Additionally, U.S. negotiators should seek agreement regarding specific timetables for the inspection, dismantlement, and verification of each nuclear and missile facility.70

This process should pave the way for a comprehensive roadmap toward North Korea’s verifiable nuclear dismantlement based on an agreed definition. These negotiations should also include discussions of possible exit ramps for sanctions, such as humanitarian waivers for certain UN sanctions. But maintaining the existing sanctions architecture is important until North Korea verifiably dismantles its facilities. Withholding full relief will permit the United States to escalate pressure in the event that North Korea once again fails to negotiate in good faith or disregards its commitments.

- Increase track II exchanges between the United States and North Korea: Track II exchanges can play a positive role in supporting diplomatic progress. These exchanges also expose North Koreans to a range of perspectives that can help break down the regime’s totalitarian control. Pyongyang increasingly includes junior research staff in these events, yet American participants are often the same individuals who have been attending since the 1990s. American participants should include a new generation of specialists focusing on Korea. American participants should also include specialists from fields other than just nuclear nonproliferation – including economics, development, communications, and agriculture. This will broaden interactions between Americans and North Koreans and make clear the potential benefits should the regime relinquish its nuclear weapons.

- Keep military options on the negotiating table: U.S. and ROK diplomats and political leaders should refrain from saying there is no military option for North Korea. While renewed military conflict with North Korea should be avoided, if Kim comes to believe the United States wants to avoid military conflict at all costs, North Korean misbehavior and aggression will become more likely. U.S. and ROK leaders should avoid any comments that leave Kim with the impression that the status quo entails no risk of military conflict.

- Refine the U.S. diplomatic approach: The credibility of the Trump administration in the eyes of the international community will be pivotal in successfully implementing a new maximum pressure campaign. Trump should therefore eschew unwarranted and inappropriate praise of the despotic North Korean leader and should likewise avoid pronouncements of progress not supported by facts on the ground.

- Strengthen coordination efforts with regional allies and partners: The United States must ensure that its regional allies share a common North Korea strategy. Washington must establish a consensus with South Korea on the need to avoid premature concessions. The United States can best achieve this through the ROK-U.S. working group led by the American and South Korean special representatives. In addition, Washington should focus on helping South Korea and Japan ameliorate their strained relations. Given the depth of their disputes, this may merely limit damage in the short-term. With time, however, the United States must help its two allies mend ties, as tensions between Seoul and Tokyo militate against a successful outcome on the Korean Peninsula.71

Washington’s lines of effort for mediation should include the Moon administration’s “two-track” strategy to separate security issues from historical disputes. Additionally, Washington should establish a trilateral working-level dialogue similar to the now defunct Trilateral Coordination and Oversight Group. The present absence of such a mechanism makes it more difficult for the three security partners to establish the robust relationships among career defense and foreign policy practitioners necessary to forge a shared vision and strategy.72 - Initiate a public diplomacy campaign: To build a common understanding of the North Korean threat and generate support for new multilateral pressure, the United States should lead a comprehensive public diplomacy campaign – ideally in conjunction with South Korea, Japan, Australia, and key European partners. This campaign should emphasize (1) the Kim regime’s refusal to make concessions; (2) Pyongyang’s continued provocations and violations of existing sanctions; (3) the desire of the United States and its allies to avoid war by achieving successes at the negotiating table; and (4) the many good faith efforts and concessions by the United States and South Korea that have yielded little so far.

- Make human rights a priority: Highlighting Pyongyang’s abysmal human rights record serves U.S. interests and values. In so doing, Washington can stand up for the oppressed, honor the best traditions of American foreign policy, and apply additional pressure on the regime. As part of an escalating information and diplomatic campaign, highlighting the regime’s abuses can help undermine the regime’s credibility, support domestic opposition, and suggest to Kim that his predicament will only worsen if he refuses to negotiate in good faith and relinquish his nuclear weapons.

- Target Chinese and Russian obstruction: Maximum pressure 2.0 should seek to build the most comprehensive and cohesive multilateral diplomatic effort possible. This must include efforts to build consensus for additional action at the UNSC. If Beijing and Moscow obstruct additional measures against North Korea, the United States should name and shame both governments wherever possible to raise the diplomatic costs of their obstruction. If this obstruction persists, the United States should shift the cost-benefit analysis of both governments. For example, Washington could move to build an increased U.S. military presence in the region and on the peninsula (with South Korean agreement). The mere announcement of this step could create new leverage and elicit increased cooperation from Beijing and Moscow. Washington could also initiate a diplomatic campaign to impose aggressive secondary and sectoral sanctions against Chinese and Russian persons that do business with North Korea or undermine existing sanctions. Beijing and Moscow are vulnerable to such sanctions.

- Stop North Korean exploitation of diplomatic privileges: North Korea uses its embassies overseas to engage in a wide range of illicit financial activity. The U.S. State Department conducted a worldwide campaign starting in 2017 to stop North Korea’s illicit activities, with a number of countries expelling North Korean diplomats and workers and even severing economic ties. The United States should seek to reduce further North Korea’s diplomatic and commercial footprint as a key element of maximum pressure 2.0.

Military Deterrence and Readiness

By David Maxwell, Bradley Bowman, and Mathew Ha

Background

ROK national security and U.S. interests in Northeast Asia depend on the military readiness of the ROK-U.S. alliance. A successful outcome on the Korean peninsula is unlikely if the alliance fails to maintain this readiness. The primary mission of the ROK-U.S. Combined Forces Command (CFC) in South Korea is to deter a North Korean attack. If deterrence fails, its mission is to defend the ROK and defeat the North Korean military to set the conditions for resolution of what the 1953 Armistice Agreement calls the “Korean question” – the division of the Korean peninsula.73

General Robert Abrams, the commander of the United Nations Command, CFC, and U.S. Forces Korea, testified in March that diplomatic activity and the September 2018 intra-Korean CMA have led to a “palpable reduction in tension when compared to the recent years of missile launches and nuclear tests.”74 Specifically, the CMA’s main terms included ending all training exercises near the North-South border and the withdrawal of all DMZ guard posts.75 The South and North negotiators intended for the CMA to serve as a trust-building mechanism.76

Although the opposing forces have started to demilitarize the Joint Security Area in Panmunjom pursuant to the CMA, the North Korean conventional military threat has not decreased. “Current modifications in atmospherics … do not represent a substantive change in North Korea’s military posture or readiness,” General Abrams testified. “The North Korean military remains formidable and dangerous, with no discernable differences in the assessed force structure, readiness, or lethality.”77 In fact, the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) completed its 2018–2019 Winter Training Cycle as scheduled.78

South Korean and U.S. troops participate in a joint military exercise in Pohang, South Korea, on April 2, 2017. (Photo by Chung Sung-Jun/Getty Images)

The North Korean military, the fourth largest in the world, remains formidable. It includes some 1.2 million active troops,79 14,000 artillery systems,80 and 2,500 armored vehicles.81 Seventy percent of the NKPA remains forward deployed between the DMZ and Pyongyang, with a large concentration of artillery systems located in the Kaesong Heights, just north of Seoul.82

Pyongyang has also developed a wide array of missiles capable of threatening U.S. forces and allies in the region and even the U.S. homeland.83 North Korea has conducted more than 80 ballistic missile tests since Kim Jong Un took power in 2012.84 In July and November 2017, North Korea launched the Hwasong-14 and Hwasong-15 ICBMs.85 The Department of Defense’s (DOD’s) 2019 Missile Defense Review assessed that North Korea has “neared the time when it could … threaten the U.S. homeland with missile attack.”86

This is particularly concerning in light of the regime’s nuclear program. North Korea has conducted six nuclear weapons tests since 2006, each with an increased yield.87 Experts assess that the regime possesses 20 to 60 nuclear warheads.88 In September 2017, Pyongyang claimed to have tested a thermonuclear weapon.89 It is unclear whether North Korea has successfully developed such a weapon, but if so, it would mark a significant upgrade in Pyongyang’s arsenal.90

North Korea’s nuclear weapons program encompasses various facilities, the most important of which is the Yongbyon Nuclear Scientific Research Center. This facility has multiple reactors, including a 5-megawatt reactor, a light water reactor, and an IRT-2000 reactor. The latter utilizes highly enriched uranium and could enable Pyongyang to boost warhead efficiency and develop smaller and lighter designs. Yongbyon also has facilities that reprocess plutonium and enrich uranium to produce weapons-grade fissile material.91

The only nuclear facility that North Korea has declared is Yongbyon. However, open-source intelligence yielded new information about another facility, in Kangson, which U.S. intelligence claims to be North Korea’s first covert uranium enrichment facility.92 Intelligence sources suspect North Korea has at least one more undeclared nuclear facility.93

North Korea’s ballistic missile program features not only ICBMs but also short-range, medium-range, intermediate-range, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles. These include solid-fuel ballistic missiles, which have a faster reaction and reload times, making them more difficult to detect.94 Pyongyang tested a variant of one such missile, the KN-15 Pukguksong-2 medium-range ballistic missile, in 201795 and again in May, July,96 and August97 of 2019. This is alarming because solid-fuel missiles could enable Pyongyang to overwhelm its adversaries’ missile defense systems, strengthening its first-strike capability.

Pyongyang also possesses a formidable arsenal of chemical and biological weapons. The North maintains an estimated 2,500 to 5,000 tons of chemical munitions, and analysts suspect it possesses a deadly arsenal of biological weapons as well.98 A former Obama administration official called North Korea’s biological weapons “advanced, underestimated, and highly lethal.”99 Pyongyang has a formidable global network that could be used to conduct a chemical and biological attack abroad – including in the United States. The regime may also be developing an electromagnetic pulse capability to target the U.S. electrical grid with nuclear-armed ICBMs.100

Approximately 28,500 U.S. troops are currently based in South Korea.101 From 2018 to 2019, in order to help defray the financial cost of the U.S. military posture, the Trump administration conducted routine burden sharing negotiations. The administration demanded a significant increase in ROK contributions for U.S. “stationing costs.” The two countries eventually reached an agreement, and the ROK assembly approved a $915 million deal.102 Because the agreement covered only one year, however, negotiations are currently ongoing for a new agreement by the end of 2019.103

The 1953 Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT) provides the legal basis for the presence of U.S. military forces in South Korea. The MDT commits both countries to mutual defense against threats in the Asia-Pacific region but notably omits specific mention of the North Korean threat.104 The negotiators sought to ensure the MDT would transcend the Kim regime’s rule. Indeed, even a cessation of North Korean hostilities would not alone determine the future status of U.S. forces on the Korean Peninsula. To change the status of U.S. forces, ROK and U.S. political leaders would need to renegotiate the terms of the MDT.105

The two allies are already considering the future of the alliance’s structure and command. Since 2003, ROK and U.S. forces have undertaken an aggressive transition program to develop independent ROK warfighting capabilities, in preparation for a transition in operational control. The goal of this effort is to give the ROK military the lead defense role. This will eventually culminate with an ROK general officer in command of CFC, supported by a U.S. deputy commander.106 A U.S. general officer will continue to command the UNC. The associated Yongsan Relocation and Land Partnership Plans have led to the consolidation of most U.S. forces south of Seoul in the Camp Humphreys-Osan Air Base area.107 While this consolidation improves logistical support and coordination and reduces costs of multiple bases throughout Korea, it also leaves U.S. forces vulnerable to North Korean missile attacks.108

Assessment

The Trump administration deserves credit for focusing on the North Korean military threat and taking actions to address it. The cessation of North Korean missile launches and nuclear tests from November 2017 to May 2019 was a notable positive development. However, the regime can easily resume missile launches (as has happened) and even nuclear tests. The suspension of those activities therefore should not be confused with a reduction of the North Korean military threat.

The U.S. military presence helps deter North Korean aggression and prevents a war on the peninsula. Yet Trump seems to think otherwise. In recent months, he has openly mulled a withdrawal of U.S. forces from the Korean Peninsula. This approach suffers from several mistaken assumptions. For instance, Trump apparently considers the U.S. military presence on the Korean peninsula an act of American charity. In reality, this presence helps deter far more costly North Korean aggression. Moreover, Trump does not seem to appreciate that the cost of the U.S. troops on the peninsula is a bargain compared to the cost of war. It is worth remembering that the Korean War (1950–1953) cost 36,000 Americans lives and an estimated $276 billion in today’s dollars.109

It is also worth remembering that South Korea’s contribution to its own defense is not insubstantial. The ROK military is composed of approximately 599,000 troops across its army, navy, and air force.110 The ROK military also operates ROK-U.S. combined information assets, such as satellites, signal, and imagery analysis, which provide early warning and detection capabilities that are essential for U.S. readiness.111

A U.S. Air Force B-1B bomber (L) and South Korean and U.S. fighter jets fly over South Korea during the Vigilant air combat exercise on December 6, 2017. (Photo by South Korean Defense Ministry via Getty Images)

In addition, South Korea hosts key U.S.-operated missile defense assets and operates its own. Specifically, U.S. missile defense systems in the ROK include one Terminal High Altitude Area Defense battery and eight Patriot Advanced Capability-3 batteries. South Korea operates three KDX-III Sejong the Great-class destroyer vessels equipped with the Aegis system. Currently, ROK is developing its Korea Air and Missile Defense multi-platform system to respond to short-range air and missile threats.112

Given the size and success of the South Korean economy, it is certainly appropriate for the administration to press Seoul to pay more of the cost of basing U.S. troops there. However, the manner and timing of such U.S. efforts matter. Initiating a contentious and public dispute with South Korea about burden sharing is shortsighted and counterproductive. Pyongyang, Beijing, and Moscow undoubtedly welcome friction animated by ill-informed populist impulses in the United States and South Korea that could potentially result in the departure of U.S. military forces.

In Singapore, Trump unilaterally announced the suspension of large-scale exercises. He adopted Kim’s rhetoric, calling the exercises “war games” and criticizing them as being provocative and too expensive.113 In the past year, while attempting to maintain military readiness, CFC scaled back numerous exercises and cancelled two major ones, Key Resolve and Foal Eagle.114 This was a mistake. Limiting ROK-U.S. military exercises has not elicited similar North Korean concessions. In fact, unilaterally cancelling or scaling back allied exercises has never resulted in significant, reciprocal, and durable concessions from North Korea.115

In addition to these conventional military concerns, North Korea’s definition of denuclearization of the entire Korean Peninsula is different from that of the United States. The Kim regime’s view is that denuclearization must include an end to the ROK-U.S. alliance, the removal of U.S. troops from the peninsula, and the termination of U.S. extended deterrence and the America nuclear umbrella over South Korea and Japan. These demands are consistent with the Kim regime’s longstanding objective of dividing the ROK-U.S. alliance so that the North can dominate the South.116

After his defection in 1991, Hwang Jong Yop, the highest-ranking defector in North Korean history and the architect of Kim Il Sung’s Juche ideology, was asked why the regime invested so much in its military yet has never executed its plan to unify the peninsula by force. His answer was simple: U.S. forces had deterred Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il. It is therefore unsurprising that a key focus for the regime is the departure of U.S. forces from South Korea.117

Since the failure of the Hanoi summit, Kim Jong Un has conducted a series of military and propaganda operations designed to increase his leverage in negotiations and generate internal support from his military and elite. These include the rehabilitation of the Sohae missile launch facility,118 a new anti-tank guided missile system test,119 combat aviation exercises,120 unusual activity at the Yongbyon nuclear facility,121 and multiple tests of a short-range tactical ballistic missiles and multiple rocket launchers in the summer of 2019.122 This indicates that Kim will continue to rely on his military to pursue a diplomatic strategy based on coercion and extortion.123

Recommendations

Ready and capable ROK-U.S. combat power is essential to deter North Korean aggression, defend South Korea, protect U.S. interests, empower effective diplomacy, and support a maximum pressure campaign. There has been no reduction in North Korea’s offensive military capabilities and no discernable change in the regime’s strategy to dominate the peninsula. CFC must be prepared to respond to the full spectrum of North Korean aggression. We recommend the following actions:

- Strengthen allied military posture in South Korea: Seoul should be encouraged to invest in additional military capacity and capability – including missile defense assets. Simultaneously, in full coordination with Seoul, the United States should deploy to South Korea additional combat power consisting of rotational or permanent forces. As these deployments proceed, it is essential to avoid any decline in capability or gap in the deployment of rotational forces. In addition to strike capabilities, the United States should deploy additional missile defense and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) assets. Additional missile defense assets, perhaps as part of DOD’s Dynamic Force Employment concept,124 could strengthen the ROK-Japan-U.S. integrated air and missile defense regional architecture, adding protection for Americans and U.S. allies.

As China refuses to take additional substantive steps, and as Kim refuses to negotiate in good faith, the United States should incrementally add U.S. combat power in South Korea. Simultaneously, Washington should make clear publicly and privately that the alliance does not seek military conflict and is prepared to resolve differences diplomatically if Pyongyang is prepared to honor its commitments in a verifiable manner. Also, as part of a systematic and ongoing effort to assess U.S. military posture in South Korea and maximize readiness, every effort must be made to address the priority lists and unfunded requirements of U.S. Forces Korea and U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. As DOD and Congress allocate finite American resources, priority should be given to requirements on the peninsula related to ISR capabilities, integrated missile defense, command and control, counter-fire systems, and prepositioned equipment. - Strengthen the new ROK-U.S. CFC’s exercise program: US. and ROK leaders must constantly assess military readiness. Accordingly, CFC’s exercise program should be as comprehensive, challenging, and realistic as possible. The ongoing exercise program must include theater-level command post computer-simulated exercises in order to coordinate joint and combined warfighting elements. If readiness declines or does not keep pace with the North Korean threat, CFC should reform the exercise program without delay. Sustained combined exercises can help set the conditions necessary for the successful transfer of operational control of CFC to an ROK General Officer. By ensuring that CFC maintains readiness through this transition process, the United States will emphasize the continued strength and unity of the military alliance.

- Address weaknesses inherent in the September 2018 CMA: The United States should press ROK negotiators to update the CMA to focus on reducing the offensive capabilities of North Korea’s frontline forces, with a specific objective of withdrawing the North’s artillery from the Kaesong Heights. This will be an indicator of the regime’s sincerity in reducing tensions. If the North does not expeditiously implement sufficient reciprocal confidence-building measures and continues to sustain its large-scale winter and summer training cycle program, the ROK-U.S. alliance should enhance deterrence and readiness by returning to large-scale exercises such as Ulchi Freedom Guardian, Foal Eagle, and Key Resolve and by developing additional exercises that include the deployment of strategic assets.

- Stabilize the burden sharing process: The United States must not allow the burden sharing negotiation process to weaken the alliance’s diplomatic unity or military strength. The United States and South Korea should quickly conclude current negotiations on mutually agreeable terms. The United States should then seek to return to a five-year process to reduce unnecessary friction in the alliance and provide financial stability and resource continuity. Failure to do so would provide Pyongyang’s Propaganda and Agitation Department an opportunity to divide the U.S.-ROK alliance.

- Strengthen the Ground-Based Mid-Course Defense (GMD) system: The U.S. GMD system is “designed to defend against the existing and potential ICBM threat from rogue states such as North Korea and Iran,” according to DOD.125 Although it currently has the capability to defend the homeland against a limited North Korean ballistic missile attack, the United States should improve the system’s reliability, capability, and capacity. Decision makers should expedite improvements to GMD interceptors, sensors, and kill vehicles. These improvements take time, and given the nature of the North Korean ballistic missile threat, there is no time to waste.

The Cyber Element

By Mathew Ha and Annie Fixler

Background

North Korea’s cyber operations generate revenue for the regime and play an important role in Pyongyang’s espionage and reconnaissance efforts. North Korea’s cyberattacks against the United States, South Korea, and allied countries continue unabated and are likely to endure, barring a more assertive response. Less than a month after the first intra-Korean summit in April 2017, the ROK government disclosed numerous DPRK intrusions against academic think tanks and financial organizations.126 Even as Kim and Trump were meeting in Hanoi, North Korean hackers were attempting to infiltrate more than a hundred companies in the United States and around the world.127 The U.S. intelligence community concluded in 2019 that North Korea’s government will continue sponsoring cyber operations “to raise funds and to gather intelligence or launch attacks on South Korea and the United States.”128

“Straight up cyber bank theft” accounts for a significant portion of North Korea’s malicious cyber activity, according to John Demers, the U.S. assistant attorney general for national security.129 Experts at the Royal United Services Institute believe these operations and the regime’s use of crypto currencies to evade sanctions are helping to finance North Korea’s nuclear and unconventional weapons program.130

To date, North Korea’s highest-profile cyberattack remains its February 2016 hack of the Bangladeshi central bank, during which the attackers pilfered $81 million. The hackers infiltrated the bank’s network and issued fraudulent requests for the Federal Reserve of New York to transfer funds to accounts the hackers controlled.131 Had the Federal Reserve not grown suspicious, North Korean hackers could have stolen up to $1 billion.

In addition to fraudulent electronic transfers, North Korean hackers have also used cyberattacks to physically empty ATMs of cash to fill regime coffers. Dating back to 2016, North Korean government-supported hackers known as the Lazarus Group (also known as Hidden Cobra) infiltrated banking networks around the world to conduct fraudulent ATM withdrawals.132 On September 13, 2019, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned Lazarus Group and two of its subordinate hacking organizations, Blunoroff and Andraiel.133 In two separate incidents, the group initiated simultaneous cash withdrawals in dozens of countries, stealing tens of millions of dollars.134 North Korea likely utilized local networks in those countries to retrieve the cash.

First Assistant U.S. Attorney Tracy Wilkison announces charges against a North Korean national for a range of cyberattacks on September 6, 2018, in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images)

North Korean hackers have also targeted cryptocurrency exchanges.135 Between hacks, mining,136 and scams,137 North Korea has generated hundreds of millions of dollars in foreign currencies and cryptocurrencies.138 In August 2019, a UN Panel of Experts estimated this total to be as high as $2 billion, accumulated over 35 attacks across 17 countries.139 While there are reasons to question this number, there is little doubt that North Korea uses the cyber domain to acquire a significant portion of its funding.140

North Korea also uses cyber operations as part of its reconnaissance and espionage missions. Pyongyang’s primary agency for cyber activity is the Reconnaissance General Bureau (RGB), which is responsible for North Korea’s terrorist, clandestine, and illicit activities.141 In February 2018, the cybersecurity firm FireEye released a report on a North Korean hacker group it calls Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) 37. From 2014 to 2017, the group infiltrated chemical, electronic, manufacturing, aerospace, automotive, and healthcare companies in Japan, Vietnam, and the Middle East for espionage purposes. FireEye concluded that the hackers’ strategic intent was to learn more about South Korea’s government, military, and defense industrial base.142 More recently, FireEye confirmed multiple North Korean APTs targeting South Korean companies, government agencies, and public services. Each group appeared to have a separate mission in support of Pyongyang’s espionage, theft, and disruption goals.143

The Wannacry malware attack offers insights into another element of Pyongyang’s cyber operations: disruption. The Wannacry malware infected more than 200,000 computers in 150 countries, locking up systems until victims paid a ransom.144 Health care services, manufacturing, and critical infrastructure sectors were severely impacted by North Korea’s most destructive ransomware attack to date.145 While fewer than 400 victims paid the ransom and hackers generated only $140,000,146 the total cost of the attack, including damage mitigation and business interruption, may have been as high as $18 billion.147 Wannacry likely aimed not to generate funds but to wreak havoc. Pyongyang is likely assessing how a similar attack synchronized with an escalation on the Korean Peninsula might affect Washington and Seoul’s ability to respond.

Assessment

North Korea’s cyber capabilities are the newest component of the regime’s asymmetric strategy. Kim Jong Un has reportedly called cyber warfare an “all-purpose sword,” granting Pyongyang the ability to “strike relentlessly.”148 Cyber operations provide North Korea with a less conspicuous way to engage in peacetime provocations and illicit activities.149 Pyongyang’s ongoing malicious cyber activities suggest it will continue its multi-pronged strategy of deception, coercion, and extortion.

The Trump administration has deployed a range of tools to combat the North Korean cyber threat. The Computer Emergency Readiness Team, jointly run by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), has issued numerous technical alerts and malware reports so that targeted industries can mitigate North Korean malware. DHS is also partnering with U.S. Cyber Command (CYBERCOM) to publicly disclose samples of North Korean malware to assist cybersecurity professionals in protecting private industry.150 It is unclear, however, whether these efforts have reduced or prevented North Korean cyberattacks.151

The Trump administration has also relied on sanctions and legal mechanisms. In September 2018, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) issued criminal charges against a North Korean computer programmer, Pak Jin Hyok, for his role in cyberattacks sponsored by Pyongyang.152 The indictment provided detailed evidence attributing these cyberattacks to the DPRK government through Pak and his company.153 In conjunction with the indictment, the Treasury Department sanctioned Pak and his company, Chosun Expo Joint Venture, which Treasury noted was likely a front company for the RGB.154

This joint Treasury and DOJ action was the first cyber-related charge the United States brought against a North Korean since the Obama administration sanctioned the DPRK government for the Sony Pictures attack of 2014.155 This time, the action directly targeted an individual and company for government-sponsored cyberattacks, undercutting the regime’s plausible deniability. More importantly, the joint action demonstrated that Washington can positively identify both the government sponsor and the individual cyber operatives responsible for attacks.

North Korea continues to wage cyberattacks, in part because its hackers receive sanctuary in China. DOJ has confirmed that North Korean companies such as Chosun Expo operate in China.156 Until early last year, RGB operated a command post in Shenyang, China.157 North Korean defectors also report that Pyongyang sends newly trained hackers to China to earn money for the regime.158 Evidence also suggests that these hackers receive additional computer science training at Chinese universities.159 If these hackers have student visas, Beijing is likely aware of their activities. Data pattern analysis also suggests North Korean internet activity emanates from India, Malaysia, New Zealand, Nepal, Kenya, Mozambique, and Indonesia,160 although it is not clear if North Korean personnel are physically operating from these nations or merely routing traffic through their networks.

A contestant in South Korea’s annual White Hat Contest reads code lines on his laptop on Oct. 21, 2015, in Seoul. Designed to train cybersecurity experts to combat North Korean and other cyber threats, the contest is jointly hosted by the ROK Defense Ministry and National Intelligence Service and supervised by ROK Cyber Command. (Photo by Shin Woong-jae/Washington Post)

Unfortunately, the FBI has concluded that public attribution will not deter North Korean hacking.161 Perhaps informed by this assessment, the Obama and Trump administrations have occasionally used offensive cyber capabilities to counter North Korea’s malign activities. During the Obama administration, the United States reportedly initiated cyber and electronic warfare operations against North Korea’s missile program.162

In 2017, CYBERCOM reportedly cut the internet access of RGB hackers as part of operations ordered early in the Trump administration.163 That operation aligns with the Pentagon’s subsequent September 2018 Defense Cyber Strategy and its goal of “defend[ing] forward to disrupt or halt malicious cyber activity at its source.”164 The Trump administration also delegated greater authority over battlefield decisions to U.S. offensive cyber operators.165 Press reporting indicates that CYBERCOM has begun to operate accordingly, but much remains classified.166

Pyongyang maintains the ability to engage in cyber-enabled economic warfare and target the ROK and U.S. economies to indirectly undermine the alliance’s military and strategic capabilities. The world witnessed a test run in 2013 with the DarkSeoul attacks against South Korean banks and media companies.167 While North Korea has yet to unleash large-scale cyber-enabled economic warfare attacks, such tactics align with Pyongyang’s “peacetime provocations” strategy of operating below the threshold of war to achieve political and economic gains that help preserve the Kim family regime.168

Pyongyang’s cyber capabilities would likely also prove useful to the regime if military conflict erupts on the peninsula. The North Korean military’s conventional war plans focus on integrating “strong surprise attacks” and asymmetric capabilities to gain an immediate advantage.169 In a military conflict, Pyongyang would likely launch cyber-attacks against ROK-U.S. command, control, communications, computer, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance nodes. The presence of cyber units within Pyongyang’s General Staff Department highlights the importance the North Korean military places on cyber.

Recommendations

North Korea uses the cyber realm to generate illicit revenue and conduct ISR operations. Even if negotiations make progress, these activities will almost certainly continue. While the Trump administration has taken steps to hold Pyongyang accountable for its malicious cyber operations, Washington must do more to deter and impose costs on the Kim regime.170

- Initiate offensive cyber operations to mitigate and deter Pyongyang’s cyber activity: The United States should undertake additional cyber operations to deter and thwart Pyongyang’s hacking. Washington should engage in cyber operations to restrict adversarial cyber capabilities. Recently reported examples that could serve as models include the dismantlement of North Korean hackers’ internet access and the joint FBI-U.S. Air Force operation to map and disrupt a global network of malware-infected computers under North Korean control.171

Washington should also use cyber-enabled information warfare options to widen social fissures between the Kim leadership and North Korean elites, who are vulnerable to information operations. Such operations should intensify if the regime does not move toward denuclearization in good faith.172 - Impose additional sanctions focused on North Korean cyber operations: Cyber-focused sanctions have been an underutilized tool to address North Korean capabilities. Washington should target foreign front companies that help fund key North Korea cyber institutions.173 One particular target that may warrant scrutiny is Malaysian company Glocom, which a March 2018 UN Panel of Experts report determined is engaged in sanctions evasion to fund the RGB.174 In September 2019, the UN Panel of Experts further recommended that member states highlight cyber when drafting future sanctions.175 Implementing this recommendation could generate momentum for both individual and collective action among UN member states.

- Pressure China, Russia, and other countries to dismantle North Korean networks in their jurisdictions: The United States should increase efforts to persuade other nations, namely China and Russia, to monitor and restrict the activities of North Korean personnel and expel those involved in malicious cyber activity. China not only provides North Korea with an outbound internet connection176 but also hosted North Korean hackers in the Chilbosan Hotel in Shenyang, China. (The hotel is now closed.)177 Since October 2017, a Russian firm, TransTelecom, has also provided North Korea an outbound internet connection.178

However, foreign nation support likely extends beyond China and Russia. If Washington has evidence to confirm reports of North Korean cyber operations routing through India, Malaysia, New Zealand, Indonesia, or other countries, it should share actionable intelligence with allies to patch vulnerable systems that are being exploited.

Washington should urge these foreign governments to expel in-country personnel responsible for the operations. If these foreign governments refuse, Washington should be prepared to impose sanctions on companies and individuals in countries under section 104(a)(7) of the North Korea Sanctions and Policy Enhancement Act (NKSPEA), which requires the president to submit a report to Congress describing “the identity and nationality of persons that have knowingly engaged in, directed, or provided material support to conduct significant activities undermining cybersecurity.”179 The administration should sanction the companies or individuals helping North Korean personnel operating overseas. - Create a joint ROK-U.S. cyber task force: The Trump administration should work with South Korea to establish a joint cyber task force to develop a combined strategy for operations, exchange cyber intelligence, and prepare defensive and offensive options.180 The task force should incorporate a joint cyber intelligence center to enhance information sharing and cyber threat detection. With South Korea suffering as many as 1.5 million North Korean cyber intrusions per day, it is imperative that Seoul responds.181 Through this task force and intelligence sharing mechanism, Seoul and Washington could more effectively share information to jointly attribute North Korea’s regime-sponsored attacks.

The two nations should also conduct joint cyber training to test interoperability, prepare for challenges the allies will confront in a military conflict with North Korea, and demonstrate shared resolve. Simultaneously, the United States should explore a similar cyber task force with Japan, ultimately aiming to create a trilateral task force capable of synchronizing defenses against both North Korea and China. - Create a cyber defense umbrella: To bolster the ROK-U.S. alliance and cyber deterrence, the United States should declare that significant cyberattacks on South Korea would trigger U.S. obligations under the Mutual Defense Treaty (as Washington and Tokyo declared in April) and work closely with Seoul to define that threshold.182

U.S. Sanctions Against North Korea

By David Asher and Eric Lorber

Background

The United States has employed economic tools of power in its policy toward North Korea since the Korean War – increasing and relaxing pressure to incentivize Pyongyang to make concessions on its nuclear program and other destabilizing activities. In the early 1990s, the Clinton administration imposed sanctions on certain DPRK government entities in response to North Korean ballistic missile and nuclear activities, but it later lifted a number of key restrictions pursuant to the 1994 Agreed Framework. Likewise, in the mid-2000s, the Bush administration pursued a global initiative targeting North Korean illicit activities and leadership finances. Following subsequent diplomatic progress, the Bush administration unwound several important restrictions, including through the removal of North Korea from the State Sponsors of Terrorism list.

As U.S. sanctions and special measures ebbed and flowed, additional, multilateral sanctions came into effect – principally through UN Security Council Resolutions (UNSCRs), such as UNSCR 1718. While circumstances have varied, this history demonstrates a repeated cycle of North Korean provocations followed by punitive economic measures that are later lifted for ultimately unreliable North Korean commitments.

The most recent round of enhanced economic pressure began during the Obama administration in response to North Korea’s fourth nuclear test, in January 2016.183 The passage of NKSPEA in February 2016, combined with both Executive Order (E.O.) 13722 and UNSCR 2270, marked a major expansion of U.S. and multilateral sanctions.

Chinese cargo trucks wait at Dandong Port on October 12, 2016, for clearance to transport goods into North Korea via the Sino-Korea friendship bridge. The bridge handles roughly half of China-DPRK trade, which accounts for around 40 percent of North Korea’s total exports. (Photo by Zhang Peng/LightRocket via Getty Images)

The Trump administration enhanced this effort by working through the United Nations to successfully secure the passage of four additional UNSCRs with an array of economic and diplomatic actions for all UN member states to enact. These included restrictions or bans on the purchase of North Korean coal, iron, lead, and seafood as well as prohibitions against North Korea’s use of expatriate labor. The Trump administration has also increased pressure by working with Congress to implement additional statutory sanctions and by issuing executive orders to strengthen sanctions that incorporate and expand the UN sanctions framework.

U.S. Sanctions Expansion Since February 2016

| US Sanctions: Executive Order/Legislation | Key Provisions |

|---|---|

| North Korea Sanctions and Policy Enhancement Act of 2016184 Effective date: February 18, 2016 | Mandated the application of sanctions related to North Korea’s proliferation, arms trafficking, money laundering, censorship, luxury goods purchases, cyberattacks, and human rights abuses. It blocked all assets of the DPRK government and its officials. |

| E.O. 13722 – Blocking Property of the Government of North Korea and the Workers’ Party of Korea, and Prohibiting Certain Transactions With Respect to North Korea185 Effective date: March 16, 2016 | Prohibits U.S. nationals from exporting or re-exporting goods, services, or technology to North Korea, and prohibits any new investments in North Korea by U.S. persons. It also imposed sanctions against both U.S. and non-U.S. persons dealing in luxury goods, minerals, and certain industries; engaging in human rights abuses; undermining U.S. cybersecurity; or promoting censorship on behalf of the DPRK government. |

| Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act186 Effective date: August 2, 2017 | Mandated a range of sanctions for purchasing or acquiring from North Korea key precious metals or other natural resources; selling or transferring to North Korea aviation fuel or providing other services; providing insurance or registration services to a vessel owned or controlled by the DPRK government; and maintaining a correspondent account with a North Korean bank. The legislation also limited U.S. assistance to governments purchasing arms or related services from North Korea, and it authorized the administration to prohibit any ships registered with countries that enable the circumvention of UNSCR requirements from landing in the United States. Finally, the legislation imposed sanctions related to North Korea’s use of slave labor. |

| E.O. 13810 – Imposing Additional Sanctions with Respect to North Korea187 Effective date: September 21, 2017 | Applied sanctions on key sectors of North Korea’s economy and on aircraft and vessels that have traveled to North Korea. Most importantly, it introduced secondary sanctions on foreign financial institutions that engage in a range of transactions involving North Korea. |

UN Sanctions Against North Korea Since March 2016

| UN Sanctions: United Nations Security Council Resolutions | Key Provisions |

|---|---|

| UNSCR 2270188 Effective: March 2, 2016 | Prohibited the supply of luxury goods to North Korea and the sale or transfer of gold, titanium, vanadium ore, and other materials from North Korea. It also placed limitations on North Korea’s sale of coal and iron, and mandated cargo inspections to and from North Korea. Finally, it froze the assets of entities of the DPRK Government and Worker’s Party of Korea and prohibited the leasing or chartering of vessels and airplanes and the provision of crew services to North Korea. |