May 9, 2019 | Monograph

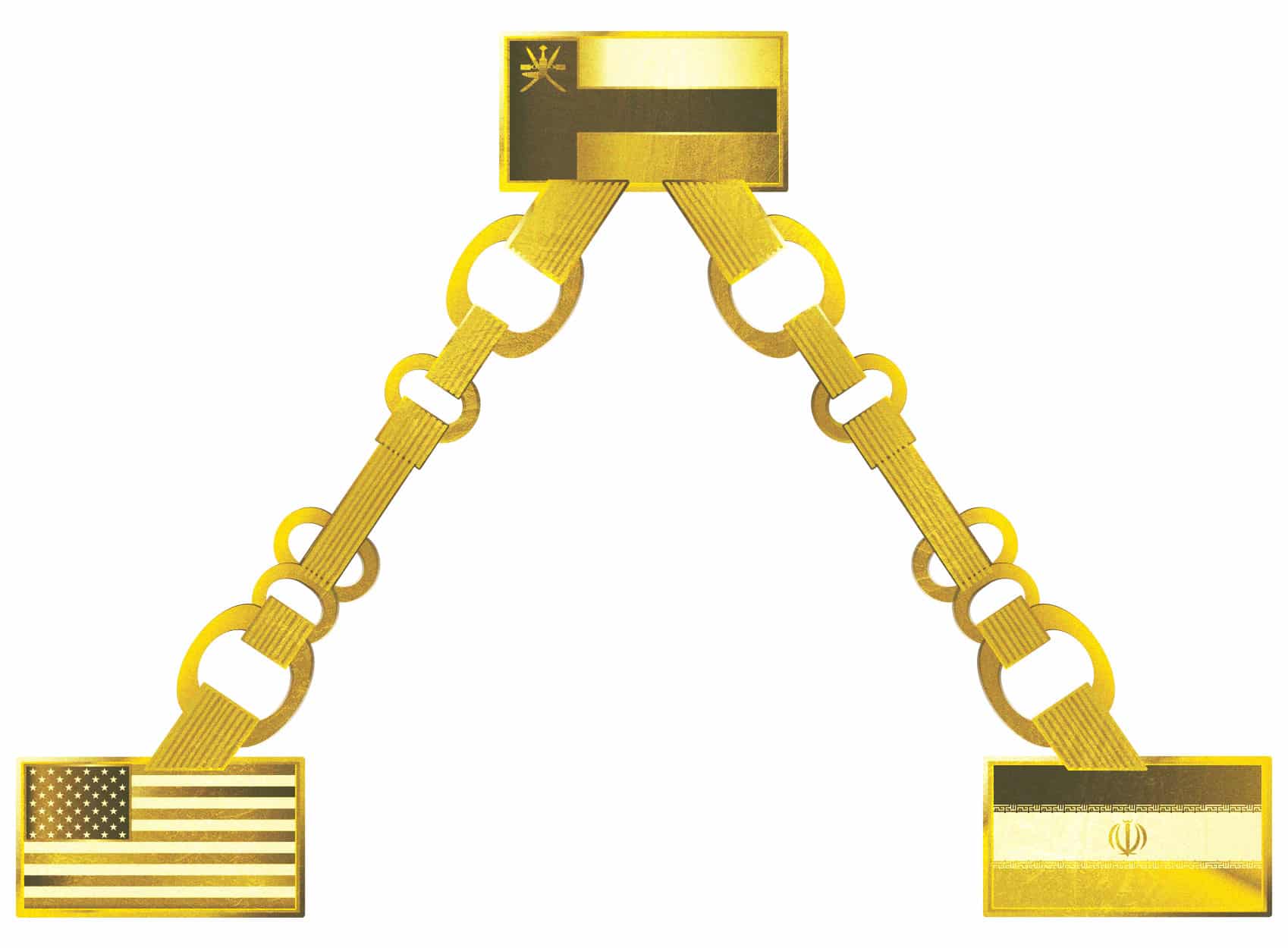

Oman in the Middle

Muscat’s Balancing Act Between Iran and America

May 9, 2019 | Monograph

Oman in the Middle

Muscat’s Balancing Act Between Iran and America

Introduction

The Obama administration praised the Sultanate of Oman just a few short years ago for establishing a backchannel between the United States and Iran that ultimately resulted in the 2015 nuclear deal, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).1 The Trump administration last year withdrew from the deal and erased what Oman viewed as a major achievement.2 Oman is now betwixt and between.

Despite the reversal of U.S. policy, Oman remains committed to diplomacy. It is often called the “Switzerland of the Middle East,”3 and Sultan Qaboos bin Said al Said, who has ruled the country since 1970, prides himself on maintaining friendly political and economic relations with Iran, as well as an alliance with the United States.

The U.S. military, in particular, continues to value its longstanding relationship with the sultanate, which grants the U.S. access to strategic air bases and port facilities close to Iran.4 Oman also works with the U.S. Navy to ensure freedom of navigation through the Strait of Hormuz, the strategic waterway through which 30 percent of all seaborne-traded crude oil passes.5

Graphic: Map of Oman and region

But Oman’s commitment to stability in the region has become subject to doubt amid reports that Iran may have smuggled weapons to the Houthi rebels in Yemen by way of overland routes through Oman.6 American, Israeli, Saudi, Emirati, and Yemeni officials alike have expressed concern and have requested more immediate action from Muscat.7 Omani officials deny that there is a problem.8

Yet Oman is undeniably drawing closer to Iran for economic and political reasons. A 2007 proposed natural gas pipeline between Iran and Oman9 – as well as other investments – offers Muscat an economic lifeline that neither its Gulf allies nor the U.S. have been able to provide. This has prompted alarm among Oman’s neighbors, notably Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). (This is not their only area of friction. Other areas include the Saudi-led war in Yemen, the UAE’s territorial purchases along Oman’s borders, and the blockade of Qatar, which is led by both Saudi Arabia and the UAE.10)

From Washington’s perspective, the real concerns could stem from Oman’s financial ties with Iran, which include entities that came under U.S. sanctions prior to the 2015 nuclear deal for their connection to the Islamic Republic’s terrorism and proliferation networks.11 A 2018 U.S. Senate report revealed that Omani banks assisted Iran in gaining access to its foreign reserves after the 2015 nuclear deal came into effect. While this transpired with the full knowledge of the Obama Treasury Department, it raises troubling questions about Oman’s efforts to provide Iran with financial assistance.12

The Trump administration’s tougher Iran policy threatens the pipeline and other economic deals with the Islamic Republic. Perhaps this is why Oman is now working to rebuild trust with the Trump administration. Indeed, the October 2018 visit by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to Muscat13 and a March 2019 agreement allowing the U.S. military greater access to Omani ports14 may have been overtures to try to strengthen ties.

It is a U.S. interest to maintain relations and foster a strong partnership with Oman. American policymakers should be sympathetic as Oman adjusts to the diametrically opposing policies of the Trump and Obama administrations. However, Washington should also demand that Muscat shift back to a truly neutral position on Iran, both politically and economically.

Illustrations by Daniel Ackerman/FDD

The U.S.-Iran-Oman Triangle

Historians often attribute Iran’s longstanding influence in Oman to a long and complex history that connects the two nations that straddle the Strait of Hormuz.15 For the purpose of this study, we will focus on the contemporary factors that have drawn the current Omani leadership to the regime in Iran, and highlight how they often conflicted with U.S. policy.

Sultan Qaboos assumed power in 1970 after he overthrew his father. The new sultan needed assistance quelling a rebellion, which had begun in 1962, in Oman’s southern Dhofar province. The United Kingdom provided training assistance to Qaboos’ troops,16 while Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Kuwait provided financial assistance.17 However, it was Iran’s Mohammad Reza Shah, at Qaboos’ request, who sent troops in 1973.18 The revolt was put down in 1975,19 yet Iranian forces remained until 1977.20

Regional dynamics changed dramatically after the February 1979 Iranian Revolution. Iran began to export its revolutionary ideology to the region, which threatened the security of the Gulf states.21 Oman, unlike its Gulf neighbors, embraced a strategy of engagement rather than hostility. In June 1979, Oman dispatched its undersecretary for foreign affairs to Tehran to ensure that preexisting agreements with Iran remained intact.22 (The Carter administration also initially sought a relationship with the new Iranian government, but that effort ended when Iranian students invaded the U.S. embassy that November, taking 52 American diplomats and citizens hostage.23)

While drawing closer to Iran, Oman pursued a strategic relationship with the United States as an insurance policy. The sultanate signed the Oman Facilities Access Agreement on April 21, 1980, making it the first Gulf state to formalize defense relations with the U.S. This allowed the U.S. to use Oman’s Masirah Island air base later that year in the failed attempt to rescue the American embassy hostages in Iran.24

When the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988) erupted, Oman reportedly gave Iraq permission to use its bases, but withdrew the approval at the request of the U.S.25 Muscat then assumed a position of neutrality throughout the war.26 In 1981, Oman joined Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar in forming the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) – an alliance largely formed to deter Iran.27 However, Oman, along with the UAE, opposed Saudi Arabia’s plan for the GCC to completely sever ties with Iran.28 Muscat had the challenge of patrolling the Strait of Hormuz with its small navy,29 and believed it needed Tehran’s assistance.30 Throughout the war, Oman maintained diplomatic relations with both Iran and Iraq. It even reportedly hosted talks between the two sides in Muscat during the war.31 Sultan Qaboos also reportedly maintained personal ties with Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.32

Meanwhile, Iran-backed Hezbollah began kidnapping Americans and Westerners in 1982. In an effort to obtain their release, the Reagan administration tried to engage Iranian pragmatists to no avail. After Hezbollah’s 1983 bombing of the U.S. marine barracks in Lebanon, the U.S. designated Iran a state sponsor of terrorism in 1984. This prohibited Tehran from receiving U.S. financial assistance and arms sales, and from purchasing dual-use items.33

As tensions escalated between the U.S. and Iran, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reportedly spent $250 million in the 1980s modernizing Oman’s military bases at Masirah Island, Sib, Thumrait, and Khasab.34 Having successfully secured the trust of both sides, Muscat served as an intermediary between Washington and Tehran regarding the return of Iranians captured during naval skirmishes.35

Following the end of the Iran-Iraq War and the death of Ayatollah Khomeini, U.S. administrations were open to improving relations with Tehran. “Goodwill begets goodwill,” President George H.W. Bush famously said to Iran in his 1989 inaugural address. But the U.S. remained alarmed over Iran’s efforts to acquire nuclear weapons and the means to deliver them, its support for terrorist organizations (especially Hezbollah, Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad, and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command), its potential to threaten shipping through the Strait of Hormuz, and its efforts to undermine the Israeli-Palestinian peace process.36

During the 1990s, ties expanded between Oman and Iran. After Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, Oman joined the U.S.-led multinational coalition to liberate Kuwait.37 As it did in the Iran-Iraq War, Oman retained diplomatic ties with all the belligerents.38 Following Kuwait’s liberation, Sultan Qaboos and his foreign minister, Yusuf bin Alawi, both argued that Iraq was a greater threat to the region than Iran. They contended that the West should talk with Iran rather than isolate it.39

In May 1990, the Omani oil minister visited Iran to explore joint ventures. Oman also reduced tariffs for Iranian vessels entering Omani waters. In 1993, the commander of the Omani navy traveled to Iran as part of a bid to ensure security in the Strait of Hormuz. In 1995, the commander of the Iranian navy toured a base in Oman. Cultural and trade agreements soon followed.40

Washington remained concerned about Tehran’s nuclear program, however. In the 1990s, the U.S. persuaded Argentina, India, Spain, Germany, and France to prohibit the sale of nuclear technology to Iran. Nonetheless, Tehran received assistance for its Bushehr nuclear power plant and missile technology from Russia, Pakistan, China, and North Korea.41

In 1995, President Bill Clinton issued Executive Order 12957, which barred U.S. firms from investing in Iran’s energy sector,42 and Executive Order 12959, which prohibited U.S. companies from trading with, re-exporting U.S. goods to, investing in, and financing loans for Iran.43 The Iran and Libya Sanctions Act of 1996 further barred non-U.S. businesses from investing more than $20 million in Iran’s energy sector.44

Following the election of Iranian President Mohammad Khatami, President Clinton sent him a letter via Oman.45 The letter indicated that the U.S. had evidence of IRGC involvement in the 1996 bombing of Khobar Towers, which killed 19 American servicemen and wounded almost 400. However, the letter also expressed interest in improving relations with Iran.46 Clinton made public remarks as well about improving relations and eased some restrictions on Iran, though most U.S. sanctions remained in place.47

The George W. Bush administration tried engaging with Iran, as well. After the 9/11 attacks, both Washington and Tehran supported the first post-Taliban government in Afghanistan. U.S. and Iranian envoys also held talks after the 2003 ouster of Saddam Hussein in Iraq. However, this cooperation soon collapsed. Iran provided weapons, training, and funding to the Taliban in Afghanistan and to Shiite militias in Iraq for their respective battles with U.S. and coalition forces.48

All the while, international concern over Iran’s nuclear ambitions continued to mount. Following revelations in 2002 about Iran’s secret nuclear sites, Tehran agreed to the 2004 Paris Agreement, which required it to suspend uranium enrichment activities.49 This was short-lived, however, and Iran resumed uranium enrichment. In response, the United Nations sanctioned Iran in 2006, 2007, and 2008 for its nuclear and missile programs, imposed asset freezes and travel bans, and prohibited arms sales.50

In 2007, the U.S. designated Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) for proliferation concerns, and the IRGC’s Quds Force for supporting terrorism.51 Washington also designated Iranian state-owned banks and persuaded more than 80 financial institutions to restrict their business with Iran.52 In 2012, the EU Council removed Iranian banks from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) financial messaging service.53

Omani officials, meanwhile, continually advised against sanctions on Iran, insisting that dialogue was the way to resolve conflicts.54 As a former Omani diplomat put it, “Iran is a big neighbor, and it is there to stay.”55 This position may have been driven as much by fear as a desire for peace. In the late 1990s, Oman uncovered a network of individuals in the country that was reportedly transmitting sensitive documents to Iran and potentially working to overthrow the Omani government in favor of an Islamist regime.56

For decades, U.S. officials viewed the Omani-Iranian relationship as “largely non-substantive,” and therefore not a threat to U.S. interests. By 2008, however, American officials noted an increase in Omani-Iranian economic, political, and military relations.57

Oman began taking a larger role in diplomacy on behalf of Iran in the 2010s. Following the storming of its embassy in Tehran in 2011, the UK downgraded diplomatic relations with Iran. Under a protecting power arrangement, Oman represented Iran’s interest in London until relations resumed in 2014.58 Similarly, Canada closed its embassy in Tehran in 2012, with Canadian Foreign Minister John Baird calling Iran a threat to global security. The following year, the Canadian Foreign Ministry named Oman “the protector of Iran’s interests in Canada.”59

All the while, Oman has maintained close ties with the United States. In addition to signing a Free Trade Agreement with Washington in 2006,60 Oman has cooperated with the U.S. on terrorism-related issues and has participated in U.S. counterterrorism training programs.61 Washington and Muscat have renewed the Oman Facilities Access Agreement every 10 years, with the last renewal in 2010. This agreement allows the U.S. to request access to use Oman’s airfields in Muscat, Thumrait, Masirah Island, and Musnanah. Oman grants most requests and allows the U.S. Air Force to store equipment at these bases. In 2000, the U.S. funded the upgrading of the Musnanah base, which cost $120 million. Washington used these air bases during Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan and in Operation Iraqi Freedom in Iraq.62

Testifying in March 2018, Commander of USCENTCOM General Joseph Votel noted, “Oman’s strategic location provides CENTCOM with key logistical, operational, and contingency capabilities; it provides important access in the form of over 5,000 aircraft overflights, 600 aircraft landings, and 80 port calls annually.”63

In March 2019, Oman signed an agreement to allow the U.S. military to access facilities and ports in Duqm and Salalah. Importantly, Duqm has the capacity to handle large ships and aircraft carriers. The ports also provide the U.S. military with access to overland routes that would enable American forces to reach the Gulf without transiting the Strait of Hormuz.64

Increased Economic Ties to Iran

Despite its growing defense ties with the United States, Omani economic ties with Iran expanded in the 2000s and early 2010s, even at a time when U.S. sanctions were highly restrictive.

Oman’s gas output doubled from 2001 to 2010, but the country’s gas consumption also soared by 180 percent in that timeframe, limiting the amount Oman could export. Moreover, starting in 2012, Oman’s gas production, which constituted 10 percent of the government’s revenue, began to decrease.65 By 2012, Oman’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) plants were running at 80 percent capacity, producing 8.4 million tons out of a possible 10.4 million tons.66

Iran, on the other hand, has the world’s second largest natural gas reserves67 but no LNG facilities for the gas it produces. Oman agreed to purchase Iranian gas as early as 2005. In 2007, the two countries drafted (but never finalized) a deal whereby Oman would import 1 billion cubic feet per day of gas from Iran for domestic use. The deal further stipulated that Oman would process 2 million metric tons per year of LNG for export. Importing Iran’s natural gas for domestic use would allow Oman to use more of its own natural gas for export. The U.S. opposed the deal and pressured Oman to obtain gas from Qatar instead. Oman did begin importing gas from Qatar in 2007,68 but these imports did not satiate Oman’s growing demand.

In the meantime, while Oman complied with UN sanctions on specific entities associated with Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs, it left the door open for other commerce with Iran. Between 2012 and 2013, Oman’s bilateral trade with Iran increased by 56 percent to $884 million. Trade decreased by the end of 2014 to $350 million.69

Problematic Iranian companies took advantage of Oman’s willingness to engage in commerce. For example, Kayson Al Omania was established in 2010 as a subsidiary of Iran’s Kayson, Inc. Though not sanctioned in the U.S., Kayson was added to the UK Export Control Organization’s Iran list in October 2013 due to concern over the company’s connections to Iran’s WMD program.70

Graphic: Map of Khasab, Oman, separated from the rest of Oman by 70 kilometers of UAE territory. Khasab juts into the Straight of Hormuz, with its narrowest point only 34 kilometers from Iran.

Additionally, the Omani government failed – or neglected – to prevent Omanis living in the coastal town of Khasab from taking advantage of smuggling opportunities to Iran. Khasab is the capital of Oman’s Musandam governorate, which is separated from the rest of Oman by 70 kilometers of UAE territory. It is located on the tip of a peninsula that juts into the Strait of Hormuz, with its narrowest point only 34 kilometers from Iran.

Omanis and Iranians have smuggled goods between Khasab and Iran since the Iranian Revolution in 1979, mostly to avoid customs and taxes. The smuggling significantly expanded after the UN began imposing sanctions on Iran in 2006.71 Goods such as clothing, electronics, household appliances, pharmaceuticals, automobiles and automobile parts, and other luxury items – often shipped from the UAE – were loaded onto speedboats that crossed the Strait of Hormuz to the Iranian island of Qeshm.72 The speedboats often returned with goats and, sometimes more covertly, drugs and undocumented migrants.73 The trip can be made in under an hour, and some speedboats make up to five trips a day.74

Interestingly, while Iran considered this illegal since the smugglers avoided Iranian taxes, Muscat regulated the activity. The local government collected taxes on all the goods and even coordinated the deliveries.75 This smuggling continues today.76

Secret Negotiations

Barack Obama’s election as president in 2008 heralded a significant shift in U.S. foreign policy, as Obama initiated diplomatic outreach to Iran.77 This afforded Oman an opportunity to broaden its ties with both countries. The idea of Oman serving as a conduit for Iran-U.S. ties was not without precedent, as Oman’s foreign minister had delivered messages to Iranian leaders from President Clinton.78 Oman revived its role as interlocutor in 2009, when Omani Foreign Minister Yusuf bin Alawi told U.S. Ambassador to Oman Richard Schmierer, “Oman can arrange any meeting you want and provide the venue – if it is totally discrete.”79 That year, Oman established a backchannel, passing messages between Washington and Tehran.80

The sultanate then went even further to bring about a nuclear deal. Seeking to foster goodwill on both sides, Sultan Qaboos’ economic advisor, Salem ben Nasser al Ismaily, facilitated the return of detainees in both countries. Ismaily negotiated the release in 2010 of three American hikers who allegedly crossed illegally from Iraq into Iran; Oman paid $500,000 per hiker in ransom. Ismaily also facilitated the return of four Iranian criminals: convicted smuggler Amir Hossein Seirafi; Shahrzad Mir Gholikan, whom a U.S. court convicted and sentenced for illegally exporting night vision equipment from Europe to Iran; Nosratollah Tajik, a former ambassador to Jordan whom the U.S. tried to extradite from the UK for seeking to export night vision equipment to Iran; and scientist Mojtaba Atarodi, a professor at Tehran’s sanctioned Sharif University, whom a U.S. court convicted for shipping banned items to Iran.81

Ismaily continued to engage with the State Department, ultimately convincing Obama officials to travel to Oman to learn more about the sultan’s vision for a U.S.-Iran dialogue. Senator John Kerry undertook several visits, as well.82

Direct talks between U.S. and Iranian officials began in 2012 in Muscat, and soon included members of the P5+1.83 They reached an interim nuclear agreement, known as the Joint Plan of Action (JPOA), in November 2013; it went into effect in January 2014.

The final nuclear agreement, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), was agreed upon in July 2015 and went into effect in January 2016. The deal was highly controversial, as it unlocked more than $100 billion in frozen funds, which Tehran could use to fund regional terror networks and other malign behavior.84 The deal was also controversial because it included “sunset provisions” on key restrictions, making it possible for Iran to develop nuclear weapons roughly a decade after the deal’s implementation. 85

As part of the deal, Iran was not allowed to have more than 130 metric tons of heavy water, a material used in reactors to produce plutonium. In November 2016, after exceeding that limit twice, Iran sent its excess heavy water to Oman.86 In May 2019, the Trump administration revoked the waiver permitting this.87

After the JCPOA was negotiated, Sultan Qaboos worked to sell it to the rest of the skeptical Arab world. 88 Oman’s neighbors were disdainful of the deal, and of Oman for helping to broker such an agreement.

GCC Trepidations

Muscat’s growing relations with Tehran have coincided with rising tensions between Oman and the other GCC members. In particular, Saudi Arabia and the UAE’s antipathy toward Iran contrasts sharply with Oman’s partnership.

Saudi Arabia has viewed Iran as a threat since the Iranian Revolution and has often tried to pressure the other GCC states to align with its Iran policy.89 In the UAE, Dubai has traditionally enjoyed strong trade relations with Tehran, but Abu Dhabi’s tougher Iranian stance has guided the UAE’s Iran policy in recent years.90

Oman has expressed some concern about Iran exporting its Islamic revolutionary ideology. However, Muscat views Saudi religious figures spreading their ultraconservative Islamist approach as a danger to Omani stability as well.91 A majority of Omanis adhere to Ibadism, a minority branch of Islam that is neither Sunni nor Shiite. This may explain why Oman has avoided the sectarian conflict that has traditionally pitted Sunnis against Shiites in the Gulf.92

In a region that often identifies allies by their enemies, the Saudis and Emiratis are deeply skeptical of Oman’s relations with Iran. In 2011, Oman claimed to have uncovered a UAE spy network seeking information on Oman’s relationship with Iran and Omani succession.93 Oman soon distanced itself from Saudi Arabia and the UAE by first facilitating the meetings – without notifying Riyadh or Abu Dhabi – that ultimately resulted in the JCPOA, and then by refusing to join Saudi Arabia’s proposals to turn the GCC into a military or political union.94 In 2018, both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi supported President Trump’s withdrawal from the JCPOA.95

Omani Foreign Minister Yusuf bin Alawi (left) speaks with Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif (right) during the United Nations General Assembly in New York City on September 20, 2017. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Another significant area of strain between Oman and the UAE concerns territorial borders. The two countries only finalized their shared border in 2008, nearly a decade after their 1999 tentative border arrangement.96 But UAE territorial purchases in Oman along the border and in Oman’s southern Dhofar province have kept tensions high.97 Furthermore, the UAE’s Louvre Abu Dhabi Museum displayed a map in 2017 that depicted Oman’s Musandam governate as UAE territory (and a different map in the museum omitted the Qatar peninsula altogether).98 Oman’s concerns about the UAE’s territorial ambitions in the region led it to prohibit GCC nationals from owning territory near border areas.99

Tensions within the GCC worsened even further in 2017 when Saudi Arabia and the UAE, along with Bahrain and Egypt, imposed a blockade on Qatar for allegedly supporting terrorism and maintaining close relations with Iran. This sparked fears that Riyadh and Abu Dhabi might subject Oman to similar treatment, though they have not made such threats.100 President Trump’s apparent support for the blockade101 also likely shocked Muscat, given that Qatar has close relations with the U.S. diplomatically and militarily. The U.S. has since called for an end to the conflict.102

Oman has defiantly maintained diplomatic relations with Qatar. To the chagrin of the Saudis and Emiratis, Oman has also expanded economic ties, with trade between the two countries soaring by 2,000 percent – worth approximately $702 million – in the first three months of the blockade.103 Barred from the quartet’s air and sea space, Qatar has relocated its flights and transshipment hub from Dubai to Oman’s Sohar and Salalah ports.104 The sultanate has seen its re-exports to Qatar increase significantly since the start of the blockade,105 and the two countries signed a memorandum of understanding in January 2018 to deepen economic and trade ties.106

Kuwait has led mediation efforts to resolve the conflict, with support from Oman. However, Omani Foreign Minister Yusuf bin Alawi is not optimistic that there will be a resolution anytime soon.107 As its concerns over Saudi and Emirati policies mount, Oman appears to be moving closer to Tehran, both politically and economically, further straining the regional divide.

Granting Iran Financial Access

In the aftermath of the nuclear deal, a U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations Majority Report, released in 2018, found that Oman’s assistance to Iran continued long after negotiations concluded.

Under the JPOA, Iran deposited $8.8 billion from oil revenue into an account at Bank Muscat. The bank repatriated about $2.4 billion in Emirati dirham banknotes and about $600 million in Omani rial banknotes to Iran, leaving $5.7 billion in the account. With the finalization of the JCPOA, Iran was allowed to access its previously frozen assets. Tehran wanted to convert its $5.7 billion in Omani rials into euros. However, because the Omani rial’s value is pegged to the U.S. dollar, such a conversion required the rials to first be converted into U.S. dollars, which was still prohibited under U.S. sanctions.108 Indeed, Secretary of the Treasury Jacob Lew testified in July 2015, “Iranian banks will not be able to clear U.S. dollars through New York.”109 In 2016, Adam Szubin, Treasury’s acting under secretary for terrorism and financial intelligence, further testified, “let me also say clearly that we have not promised, nor do we have any plans, to give Iran access to the U.S. financial system, or to reinstate what’s called the ‘U-turn’ authorization.”110

Nonetheless, in an attempt to assist Iran in accessing these funds, Bank Muscat contacted the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC). In February 2016, Treasury issued Bank Muscat a specific license, valid for one year, authorizing it to convert both Iran’s rials and unlimited future Iranian deposits to euros through “any United States depository institution … involved as a correspondent bank.” The license’s inclusion of future Iranian deposits was at Bank Muscat’s request, as the bank was concerned that Iran would withdraw its $5.7 billion, negatively affecting the bank’s balances. In an attempt to gain an economic advantage, the director of OFAC noted that Oman asked “to be the only jurisdiction to control the flow of Iranian funds into the international financial system,” though OFAC refused this request.111

OFAC officials contacted two American banks that maintained correspondent relationships with Bank Muscat “to encourage their participation with Bank Muscat,” but both declined due to the legal and compliance risks, as well as reputational concerns in doing business with Iran.112

In April 2017, a German commercial bank proposed lending the Central Bank of Iran euros and allowing repayment with Omani rials, thus avoiding any conversions into U.S. dollars and avoiding the U.S. financial system. OFAC sent the German bank a comfort letter, indicating approval of the proposed transaction. A senior State Department official believes that Bank Muscat and Iran converted the $5.7 billion using European banks and in small increments.113

Deepening Economic Ties

Following the implementation of the JCPOA, the U.S. and its European partners actively encouraged investment in Iran. By the end of 2016, bilateral trade between Oman and Iran rose to $886 million and reached over $1 billion by the end of 2017.114

As expected, Oman and Iran renewed plans dating back to 2007 to build an LNG pipeline between their countries.115 In 2013, with nuclear negotiations between Iran and the world powers underway, the two countries signed a memorandum of understanding for Iran to begin exporting gas to Oman in 2015 for 25 years, a deal valued at around $60 billion. The deal also included an agreement for a gas pipeline between the two countries “as soon as possible.”116 Iranian media reported in November 2016 that representatives from the National Iranian Gas Export Company and Oman Ministry of Petroleum met with representatives of French Total, British Royal Dutch Shell, and Korea Gas Corp to discuss the project.117 In February 2017, Iranian officials further emphasized their plans to export gas to Oman by 2020.118

Muscat additionally sought to make it easier for Iran to conduct business in Oman. While Oman used to vigorously vet all Iranian visa applications,119 the sultanate agreed in March 2016 to issue 1,000 visas for Iranian businesspersons per year. Furthermore, the chairman of the Oman Chamber of Commerce and Industry said he did not think the government should confine the number of visas, noting, “If there is a need for 10,000 visas, let us issue 10,000 visas.”120 As of May 2018, Iranian tourists no longer need a pre-entry tourist visa to visit Oman.121

After the implementation of the JCPOA, Oman and Iran were quick to strengthen banking relations. In February 2016, the head of Iran’s Central Bank said, “We will not forget the support of the country of Oman during the difficult time of sanctions, and we hope that … this friendship and cooperation is strengthened and by removing some obstacles we [can] facilitate banking connections in the two countries.”122 Bank Muscat received regulatory approval to open a representative office in Iran in April 2016.123 In March 2017, the Central Bank of Oman and the Central Bank of Iran signed a memorandum of understanding to promote trade exchange and encourage investment.124

In May 2017, Iran’s Bank Melli and Bank Saderat announced the resumption of operations in Muscat.125 The U.S. Treasury had designated Bank Melli for involvement in Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs, and Bank Saderat for channeling funds to terrorist organizations on behalf of the Iranian government.126 Both banks maintained branches in Oman after the U.S. imposed sanctions on them in 2007,127 and it is unclear if they ever fully ceased operations. Bank Melli was delisted as part of the JCPOA,128 but the U.S. re-imposed sanctions on it on November 5, 2018, pursuant to its withdrawal from the accord.129 Bank Saderat was never delisted.

Graphic: Map of ports in Oman and Iran

Oman and Iran found other ways to cooperate as well. In February 2014 – less than a month after the implementation of the JPOA – Iran announced it would invest $2 billion in the Omani ports of Sohar and Salalah, as well as $4 billion in the industrial port of Duqm. The Duqm investment would include establishing 100 large oil and gas tanks and an iron-smelting plant.130

On January 27, 2016 – just days after implementation of the JCPOA – an Omani sovereign wealth fund and Iran Khodro Industrial Group, Iran’s largest automaker, signed a memorandum of understanding for a $200-million joint venture auto plant in Duqm.131 The Islamic Republic News Agency reiterated their plans to launch the auto manufacturing plant in January 2017.132 Iran has previously used its carmakers for overseas procurement for its nuclear and missile programs.133 In 2010, Treasury sanctioned Iran Khodro’s main shareholder, Industrial Development and Renovation Organization (IDRO) of Iran,134 and the Obama administration imposed sanctions on the entire Iranian auto sector in 2013.135 IDRO’s designation was removed as part of the JCPOA136 but was reinstated on November 5, 2018.137

Additionally, Iranian cement producer Hormozgan entered an agreement with an Omani company in May 2017 to establish a new cement company called Hormuz Al Anwar in Duqm.138

There have been no updates on the above-mentioned investments since they were announced. The return of sanctions on Iran makes it even less likely that these deals will come to fruition. Oman has instead turned to Chinese investment in its ports.139

However, beginning in 2016, Oman’s Sohar and Salalah ports also began increasing their shipping links with Iran. The Iranian port city of Bandar Abbas opened a direct service with Sohar early that year.140 In March, the Salalah port signed a memorandum of understanding with Bandar Abbas’ Shahid Rajaee Port and the Shahid Beheshti Port in Chabahar.141 According to Treasury, Shahid Rajaee “played a key role in facilitating the Government of Iran’s weapons trade.”142 Under the 2016 agreement, the three ports will work together to increase trade and modernize the infrastructure of the two Iranian ports.143 Following a May 2016 contract, India now operates the Chabahar port.144

In early 2016, a ship of the Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL), Iran’s national maritime carrier, made its first call to Sohar.145 Treasury designated IRISL in 2008 for its illicit commerce activities on behalf of Iran’s Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistics (MODAFL), another designated entity.146 Like IDRO, IRISL was delisted as part of the JCPOA147 and relisted on November 5, 2018.148

In December 2017, Iran’s Mehr News reported that Iran’s Khorramshahr port also opened a shipping line with Sohar, with plans for more shipping lines between Sohar and both Chabahar and Bushehr, where Iran built a nuclear power plant. Additionally, the Omani ambassador to Iran noted, “a joint airline between the two sides is also on the agenda.”149

Yemen Conflict

Amid increasing economic cooperation, reports surfaced that Iranian weapons shipments to the Houthis, a Shiite rebel movement in Yemen, were crossing through Oman. While there is no evidence of the Omani government engaging in weapons smuggling on behalf of Iran, U.S. and Gulf officials raised concerns that the Omani government was not taking enough measures to halt the flow of weapons.150

Iran has long supported the Houthis with weapons, money, and training in their battle for control of war-torn Yemen. The New York Times reported in 2012 that Iranian aid to the Houthis resembled the weapons and training the Quds Force provided to insurgents in Iraq and to President Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria.151 Likewise, the Financial Times quoted a Hezbollah commander stating that the Houthis have trained with Hezbollah in Iran and Yemen. The Financial Times also noted that Houthi officials have reportedly visited Beirut, and the Houthi television channel al-Maseera is based in Beirut’s Hezbollah-controlled suburbs.152

In 2013, the U.S. designated Khalil Harb, who was responsible for Hezbollah’s activities in Yemen and for laundering currency to the country. The U.S. and UN have also designated several Houthi leaders for threatening Yemen’s peace and stability.153 In April 2015, the UN Security Council imposed an arms embargo on the Houthis.154 Since then, U.S. warships have intercepted several Iranian weapons shipments intended for the rebels.155

Oman, which shares a 288-kilometer border with Yemen, is the only Gulf Arab country that has not participated in the Saudi-led military campaign against the Houthis, preferring to remain neutral and try to negotiate an end to the conflict.156 As early as April 2015, Oman called for the withdrawal of the Houthis and pro-Saleh forces, the reinstatement of President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, the conversion of the Houthis into a political party, and the inclusion of Yemen to the GCC, among other steps.157 A month later, a private American plane flew some Houthi representatives to Muscat for talks with U.S. officials.158 Secretary of State John Kerry personally met with Houthi representatives in Oman in November 2016 in an attempt to implement a ceasefire and peace plan.159

Oman played host again in March 2018, this time for the Houthis and Saudi Arabia.160 Most recently, Oman received a plane carrying 50 wounded Houthi rebels in December 2018. Their treatment in Oman was a key condition for the rebel group to participate in UN-sponsored peace talks.161 Oman has also secured the release of Americans and other hostages held by the Houthi rebels.162

The Yemen conflict has undoubtedly strained Oman’s relations further with Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The war has led to instability on Oman’s border with Yemen. Oman is also wary of the UAE’s military projection into the region, especially when combined with its territorial purchases in Oman. Saudi Arabia and the UAE, meanwhile, have raised frustrations regarding Oman’s engagement with the Houthis and about reports of weapons being transported through Omani territory to them.163

A Saudi-owned daily first reported in September 2016 that allies of Yemen’s government found weapons intended for the Houthis on trucks with Omani license plates.164 In response to the accusation, Omani Foreign Minister Yusuf bin Alawi said, “There is no truth to this. No weapons have crossed our border.”165 However, other credible news outlets, independent nonprofits, and the UN have since reported that Iran has been using overland routes through Oman to send weapons to the Houthis.

According to a detailed Reuters report, the shipments via Oman have included anti-ship missiles, surface-to-surface short-range missiles, small arms, and explosives.166 In addition, Bloomberg reported that Iran could be sending its missile experts to Yemen.167

In March 2017, the group Conflict Armament Research (CAR) released a report analyzing seven Houthi unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), known as Qasef-1, used against the Saudi-led coalition. Six of them reportedly entered Yemen by land through Oman. According to CAR, the Qasef-1 shares a “near-identical design and construction characteristics” with Iranian UAVs.168

One of the missiles the Houthis have used against Saudi Arabia is the Burkan-2H, which is a copy of the Iranian Qiam-1.169 The Yemeni Armed Forces did not possess the Burkan-2H,170 meaning the Houthis could not have acquired the technology from Yemeni military officials or by looting military arsenals. Thus, the Houthis likely received the military equipment from Tehran. According to its January 2018 report, the UN Security Council’s Panel of Experts on Yemen considers a land route through Oman to be the “most likely” way the Burkan-2H arrived in Yemen. The second most likely explanation, according to the report, was a sea route through Oman. Prior to January 2017, only 25 percent of containers at Oman’s Salalah port were subject to thorough inspection, making it possible that parts of the missile passed through this route. The 2018 report also notes that an arms supply route through Oman was still possible, as interdiction is “dependent on [the] effectiveness of control checks” at busy border control posts.171

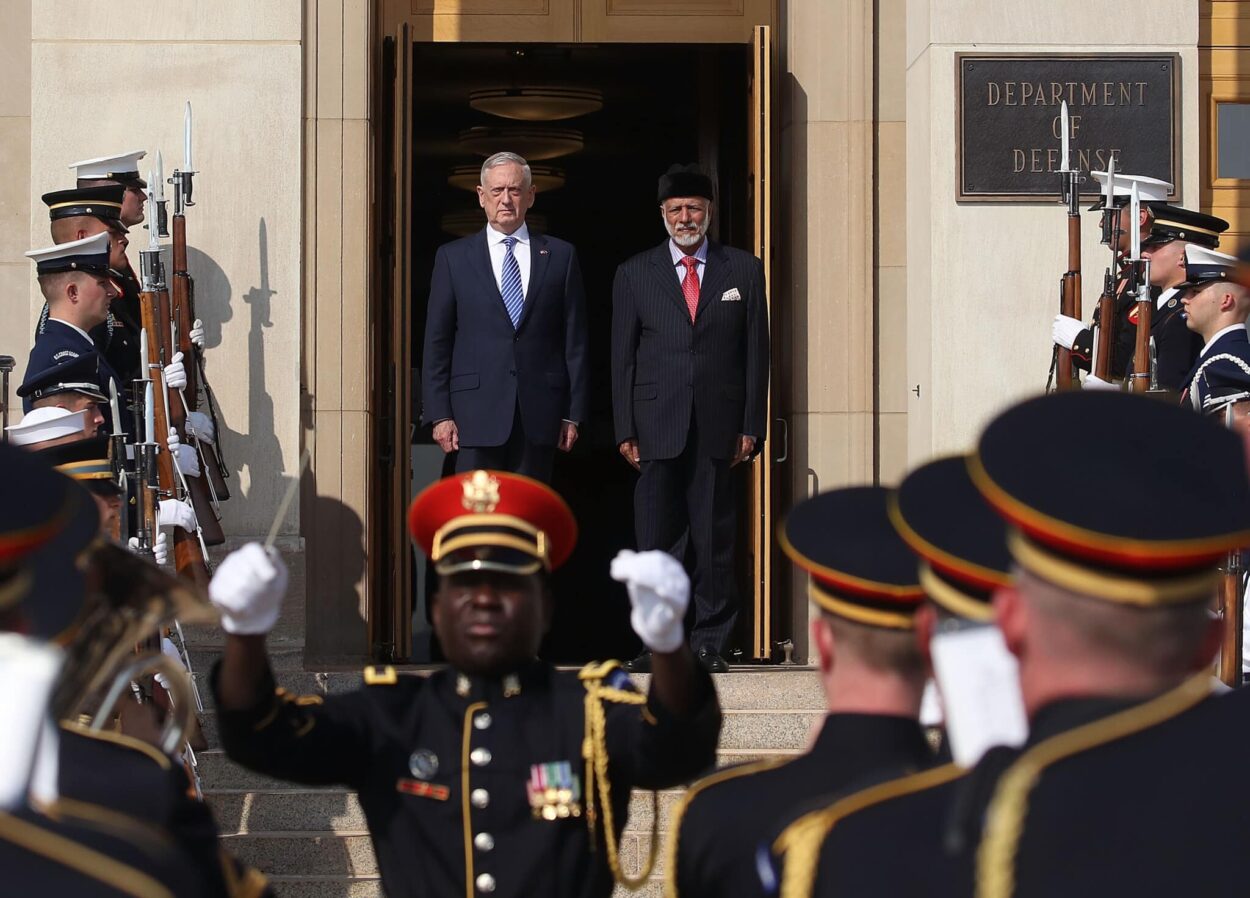

U.S. officials have conveyed their concerns to Omani authorities several times since 2016. In March 2017, then-Secretary of Defense James Mattis met with Sultan Qaboos and reportedly discussed arms trafficking into Yemen.172 Saudi, Yemeni, Emirati, and Israeli officials have expressed similar concerns.173 Omani officials, meanwhile, continued to deny these reports.174

Then-U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis (left) hosts Omani Foreign Minister Yusuf bin Alawi (right) at the Pentagon on July 27, 2018. (Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty Images)

Muscat has nevertheless made some efforts to strengthen its border security. Oman officially closed its border with Yemen in early 2016 “over fears of militant attacks,” according to the Associated Press,175 and reportedly began building a fence along the border,176 with some assistance from the United States.177

Border security was an issue for the U.S. and Oman as far back as 2001, with the presence of al-Qaeda operatives in Yemen.178 Even then, the border was only partially defined.179 Military analyst Anthony Cordesman told Al-Monitor in June 2018 how easy it can be to smuggle through Oman. First, the “difficult terrain” results in “all kinds of paths and small areas” that are difficult to secure, making it “fairly easy to cut across.” Additionally, tribes in both Oman and Yemen “don’t necessarily recognize the border.” Moreover, weapons smugglers might be using established drug smuggling routes.180

Even if the overland smuggling routes were closed off, the Iran-Oman port deals in Sohar, Salalah, and Duqm provide opportunities for illicit trade. Some Iranian entities operating in this sphere were previously sanctioned by the U.S. for terrorism or proliferation,181 and there is no indication that any of them have halted their illicit activities. Additionally, it is unlikely that the aforementioned smuggling between Khasab and Iran has ceased, making it possible for weapons parts to be transported across the Strait of Hormuz.

Meanwhile, Syrian airline Cham Wings began direct flights from Damascus to Muscat in 2015.182 Treasury sanctioned Cham Wings in December 2016 for “transport[ing] militants to Syria to fight on behalf of the Syrian regime.”183 The airline may have also transported weapons and militias at the behest of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps to Syria.184 It is possible that the airline has been bringing weapons, parts, personnel, or cash on behalf of Iran into Oman to transship to Yemen. Indeed, it is unclear why else this air bridge was established. As Under Secretary of the Treasury for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence Sigal Mandelker observed last year, “People do not go on vacation in Syria.”185

Beginning in February 2019, Iranian airline Qeshm Air began flights between the Iranian island of Qeshm and Muscat.186 The airline was previously owned by Babak Zanjani, who helped the Iranian government bypass international sanctions on its oil. After he was convicted of withholding nearly $3 billion from the Iranian government, the Iranian Oil Ministry assumed control of the airline.187

Omani officials say that smuggling is no longer a problem.188 To Muscat’s credit, there have been no major reports of weapons smuggling through Oman in the last year. The announcement of a significant U.S.-Oman port agreement in March 2019 also likely signifies that tension over the weapons smuggling issue has diminished.189

Concerns for the Future

There is nothing inherently wrong with Oman’s neutral foreign policy in the Middle East. However, Oman’s neutrality is debatable. Indeed, Omani officials continue to insist that sanctions are the wrong policy and that engagement with Iran is the best way forward. This is not a neutral position. If anything, this is a policy that advocates for Iran’s interests.

Since the U.S. began reinstating sanctions on Iran in 2018, neither Oman nor Iran announced the cancellation of any economic deals. Omani officials privately assert that there is no Iranian business in Duqm and that the Khodro deal fell through.190 However, Iran claims that trade with Oman is strong despite the return of U.S. sanctions,191 and Iranian media continue to trumpet economic deals between the two countries.192 One outlet reported that Omani officials are interested in investing in the Chabahar Free Trade Zone.193 The Tehran Times claimed that Oman’s oil minister would continue with plans for the gas pipeline.194 Several articles in Iranian media reported that Iranian companies would invest in an industrial park near Muscat by April 2022 to produce goods using nanotechnology.195

There was also an Iranian media report of a new direct shipping route between Iran’s port city of Jask and Oman’s port of al-Suwaiq,196 as well as an announcement from Iran’s Chamber of Commerce, Industries, Mines and Agriculture that “all Oman ports are open to Iranian ships.”197 The two countries reportedly signed a memorandum of understanding in April 2019 for greater military cooperation and engaged in joint marine rescue drills.198 The Times of Oman also reported that Oman is considering “enhancing air transport ties with Iran.”199

Admittedly, Oman needs the commerce. Oman’s economy is small compared to most of its Gulf neighbors. The sultanate’s GDP in 2017 was $70.7 billion, compared to Saudi Arabia’s $686.7 billion, the UAE’s $382.6 billion, Qatar’s $166.9 billion, and Kuwait’s $120.1 billion.200 Oman’s oil reserves are more limited and will run out sooner than its neighbors’ reserves.201 In addition, low oil prices have resulted in budget deficits for the last four years. Oman’s deficit in 2015 was 17 percent of GDP, rose to 20 percent in 2016, and decreased to 13 percent in 2017 and to 7 percent in 2018.202 As a result, the government was forced to cut subsidies on housing, fuel, and other public goods.203 It was also forced to borrow money from local and international markets and issue over $11 billion in bonds.204

Omani Sultan Qaboos bin Said al Said in Muscat, Oman on November 27, 2010. (Photo by John Stillwell-Pool/Getty Images)

On top of that, three major credit agencies have downgraded Omani debt to junk over the last three years.205 And like many other Middle Eastern states, Oman has high unemployment, which reached 17.5 percent in 2016. Following unemployment demonstrations in January 2018, the Omani government promised to create 25,000 jobs and imposed a ban on hiring expatriates.206

But increasing trade with Iran – licit or illicit – will come with a price. At a minimum, Oman first needs to return to genuine neutrality vis-à-vis Iran. This should include a greater effort to halt illegal shipments through its territory. But Washington should demand more, particularly if Oman is to remain a valued ally.

Complicating all of this are concerns about succession. Sultan Qaboos has ruled Oman since 1970, but he is 78 years old and suffering from terminal cancer since at least 2014.207 Yet Qaboos has no heirs, no living brothers, and no named successor. According to Omani Basic Law, upon the death of the sultan, the royal family council is to choose a new sultan within three days. If the royal family council fails to agree on a selection, four advisory bodies are to open a sealed letter from Qaboos listing his ranked choices for his successor.208 Unfortunately, this leaves a lot to chance.

Recommendations

The U.S. must make sure that Muscat does not draw closer with Tehran. Therefore, Washington should consider the following policy recommendations:

- Monitor Iranian businesses operating and investing in Oman. Due to the strong economic relations between Oman and Iran, and specifically the presence of sanctioned Iranian companies potentially operating in Oman, U.S. intelligence agencies should investigate and determine whether illegal activity is occurring. Maintaining an open channel with Muscat should lead to more cooperation and interdiction.

- Continue pressuring Oman to halt illegal weapons shipments, but also continue providing military assistance for security-related issues.S. officials should continue to convey any concerns about illegal weapons shipments to Omani officials. At the same time, the U.S. should continue to provide Oman with assistance, both financial and logistical, on securing its border, patrolling its territory and waters, and halting any illicit shipments.

- Sell LNG to Oman. Oman needs a way to import natural gas, and the United States would prefer that Iran not be the source. As it happens, U.S. LNG exports quadrupled in 2017.209 Oman would not be the first Middle Eastern country to receive U.S. exports of LNG. Louisiana’s Cheniere Energy’s Sabine Pass plant has delivered LNG to Kuwait and Dubai.210

- Offer conditional economic assistance. While the U.S. should continue providing security assistance, Washington could further incentivize Muscat by offering an economic aid package, such as subsidized LNG or investment in Omani ports or infrastructure. However, any economic assistance should hinge on Muscat halting all illicit shipments through its waters and territory, and shunning deals with Iran.

- Continue to use Oman as a facilitator. The U.S. can benefit from having an ally to pass messages and facilitate meetings with governments with whom it does not have relations. Washington should continue to encourage Omani involvement in regional conflicts to advance U.S. interests, so long as Oman maintains a truly neutral position.

- Encourage a more consistent Iran policy across the GCC. Oman is not the only GCC country that has problematic ties with Iran. Qatar has maintained both political and economic relations with Iran, and those relations have grown stronger since Saudi Arabia and others enacted a blockade on Qatar in 2017.211 In addition, while the UAE has raised concerns about Iran’s regional activity, it historically has had strong economic relations with Iran. In particular, the emirate of Dubai is a major hub for re-exports to Iran. If the U.S. asks Oman to curb its relationship with Iran, it should ask the same of its other GCC allies.

- Ease tensions between Oman and both Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are understandably frustrated with Oman’s relationship with Iran, and their concerns about illegal weapons shipments to the Houthis are legitimate. However, Oman’s concerns about Saudi and Emirati policies are also valid. If Saudi Arabia and the UAE isolate or challenge Oman, then Oman will only draw closer to Iran. Washington should encourage Saudi Arabia and the UAE to engage with Muscat and provide assurances that they do not plan to isolate Oman or interfere in Omani politics.

- Ensure continued strong relations with the next Omani sultan. When the time comes for the Omani royal family court to choose the new sultan, the U.S. should prevent foreign interference in the process. The U.S. should also work to ensure that U.S.-Omani relations remain strong, and that the new leader does not seek to bring the sultanate further into Iran’s embrace.

The U.S.-Omani alliance has proven beneficial to both parties for two centuries, and Washington is not keen to see that end. But an alliance with the United States comes with certain responsibilities. America must clearly and respectfully convey them.