January 5, 2015 | FDD’s Long War Journal

Analysis: Osama bin Laden’s Documents Pertaining to Abu Anas al Libi Should be Released

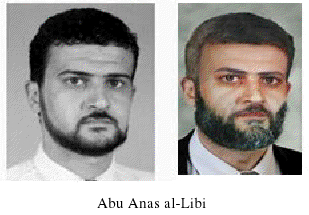

A senior al Qaeda operative known as Abu Anas al Libi has died in the US as he was awaiting trial. Al Libi was captured in Tripoli during a raid by US forces in late 2013. He had been wanted for his role in the August 1998 US Embassy bombings for more than a decade prior to his arrest.

The US government has in its possession numerous pieces of evidence concerning al Libi's al Qaeda role, including files recovered in May 2011 from Osama bin Laden's home in Pakistan.

The Long War Journal has consistently advocated for the release of bin Laden's files. The Obama administration has released just 17 documents, and a handful of videos, from a total cache of more than 1 million files. Many more of these files, if not almost all of them, should be declassified and released. There are no sources or methods to protect, as everyone knows how this information was obtained. The only files that should remain classified are those that have a direct bearing on the US government's current counterterrorism operations against al Qaeda.

Now that al Libi has passed away, the US government has another opportunity to be more transparent with respect to bin Laden's files. After all, at least some of the documents probably would have been released to the public during al Libi's trial.

Just weeks ago, in mid-December, Benjamin Weiser of The New York Times reported that US prosecutors were seeking to use files recovered during the raid on bin Laden's compound in al Libi's trial.

A close reading of the Times' account reveals that prosecutors intended to use at least five separate letters recovered in bin Laden's safe house.

It does not appear that any of these letters were included in the set of 17 documents released by the Obama administration through the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. None of Abu Anas al Libi's letters to al Qaeda's leaders were released.

The first letter described by the Times is from Atiyyah Abd al Rahman, a senior al Qaeda leader, to bin Laden dated June 19, 2010. Rahman explained that al Libi was one of “the last brothers” to be released from Iran. Al Libi “came only a week ago and I met him and sat with him,” Rahman wrote, according to the Times' summary. Rahman appointed al Libi to al Qaeda's security committee. “It is normal for any person after a long absence, especially in jail, that he needs some time to figure out how things work,” Rahman noted. Rahman recommended that bin Laden send al Libi a letter, because al Libi was seeking “reassurance.”

A second letter, dated Oct. 13, 2010, is a five-page missive from al Libi to Osama bin Laden. “Your forever lover, Your brother,” al Libi signs the letter. Al Libi explains, according to the Times, that the al Qaeda “brothers,” including bin Laden's sons and other al Qaeda operatives, fled to Iran under orders from Taliban leader Mullah Omar.

A third letter from Rahman to bin Laden was written “[a]bout a month later,” according to the Times, meaning it was penned sometime in November 2010. Rahman recommended that al Libi be accepted back into al Qaeda's leadership ranks. Rahman described al Libi as “determined,” “visionary,” and “difficult somewhat,” but also noted that bin Laden knew him. Interestingly, Rahman complained that al Libi had violated al Qaeda's operational security regulations by “contacting his family in Libya, despite knowing that we don't allow any communications.”

Al Libi “knows that he was wanted by the Americans,” Rahman wrote to bin Laden, according to the Times' summary. “He contacted them via phone repeatedly!”

In a fourth letter, written in March 2011, al Libi requested permission to join some other operatives who were returning to Libya to fight against Muammar al Qaddafi's regime. It is better to “move out sooner rather than later” al Libi wrote.

Rahman forwarded al Libi's letter to bin Laden, the Times reported, and Rahman explained to bin Laden that he approved al Libi's request. This is the fifth letter prosecutors sought to introduce. Rahman noted that al Libi was “a little upset with me for the delay in getting back to him.”

A “builder of al Qaeda's network in Libya”

Al Libi did in fact return to his native Libya. As a member of al Qaeda's security committee who returned to North Africa only after receiving permission from his superiors in al Qaeda (Rahman), it is safe to assume that he was doing the terrorist organization's bidding when he set up shop in his homeland.

Indeed, as The Long War Journal previously reported, an unclassified report published in August 2012 highlighted al Qaeda's strategy for building a fully operational network in Libya. The report (“Al Qaeda in Libya: A Profile”) was prepared by the federal research division of the Library of Congress (LOC) under an agreement with the Defense Department's Combating Terrorism Technical Support Office (CTTSO).

Abu Anas al Libi played a key role in al Qaeda's plan for the country, according to the report's authors. He was described as the “builder of al Qaeda's network in Libya.”

Al Qaeda's senior leadership (AQSL) has “issued strategic guidance to followers in Libya and elsewhere to take advantage of the Libyan rebellion,” the report reads. AQSL ordered its followers to “gather weapons,” “establish training camps,” “build a network in secret,” “establish an Islamic state,” and “institute sharia” law in Libya.

Abu Anas al Libi was identified as the key liaison between AQSL and others inside the country who were working for al Qaeda. “Reporting indicates that intense communications from AQSL are conducted through Abu Anas al Libi, who is believed to be an intermediary between [Ayman al] Zawahiri and jihadists in Libya,” the report notes.

Al Libi is “most likely involved in al Qaeda strategic planning and coordination between AQSL and Libyan Islamist militias who adhere to al Qaeda's ideology,” the report continues.

Al Libi and his fellow al Qaeda operatives “have been conducting consultations with AQSL in Afghanistan and Pakistan about announcing the presence of a branch of the organization that will be led by returnees from Iraq, Yemen, and Afghanistan, and by leading figures from the former LIFG.” The term “LIFG” refers to the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, an al Qaeda-linked jihadist group formed in Libya in the 1990s.

One of al Libi's key allies inside Libya was another senior al Qaeda operative, Abd al Baset Azzouz, who has been close to al Qaeda's senior leaders for decades.

Azzouz was sent to Libya by Zawahiri and “has been operating at least one training center.” Azzouz “sent some of his estimated 300 men…to make contact with other militant Islamist groups farther west.”

Azzouz was reportedly captured in Turkey last month. [See LWJ report, Representative of Ayman al Zawahiri reportedly captured in Turkey.]

Release bin Laden's files

The Obama administration made a concerted push to portray Osama bin Laden as a doddering old man who was operationally irrelevant. Citing bin Laden documents shown to him by the White House, the Washington Post's David Ignatius described the jihadist leader as a “lion in winter.” CNN's Peter Bergen similarly reported that bin Laden was in retirement at the time of his death. The Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, working off of only those documents provided by the Obama administration, portrayed bin Laden as being sidelined.

What we know about Abu Anas al Libi's al Qaeda role challenges all of these assessments. He was reintegrated into al Qaeda's chain of command after his release from Iranian custody. His role was approved by Rahman, who served as one of bin Laden's top subordinates before being killed in a US drone strike. Rahman made sure that al Libi joined al Qaeda's security committee — an internal body that is not factored into any public assessments of al Qaeda's structure or hierarchy. And al Qaeda approved al Libi's return to Libya. Other evidence subsequently unearthed by the US government shows that al Libi was acting as one of al Qaeda's top operatives in North Africa at the time of his capture.

This evidence should be released to the public, so we can judge for ourselves how al Qaeda operates.

In addition, any documents or files recovered from bin Laden's compound that deal with the August 1998 US Embassy bombings should be released as well. After al Libi was captured in Libya, his family claimed he had played no role in the twin attacks, which were al Qaeda's most successful operation prior to Sept. 11, 2001. However, there is abundant evidence, including testimony given before a US district court, indicating that al Libi was a key player in the bombings. Releasing any bin Laden files further implicating al Libi in the East Africa attacks would only strengthen the US government's case to the public.